Class Struggle Between the Coloured T-Shirts in Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pluralistic Poverty of Phalang Pracharat

ISSUE: 2021 No. 29 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 12 March 2021 Thailand’s Elected Junta: The Pluralistic Poverty of Phalang Pracharat Paul Chambers* Left: Deputy Prime Minister and Phalang Pracharat Party Leader General Prawit Wongsuwan Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prawit_Wongsuwan_Thailand%27s_Minister_of_D efense.jpg. Right: Prime Minister and Defense Minister General Prayut Chan-ocha Source:https://th.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E0%B9%84%E0%B8%9F%E0%B8%A5%E0%B9%8C:Prayu th_2018_cropped.jpg. * Paul Chambers is Lecturer and Special Advisor for International Affairs, Center of ASEAN Community Studies, Naresuan University, Phitsanulok, Thailand, and, in March-May 2021, Visiting Fellow with the Thailand Studies Programme at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2021 No. 29 ISSN 2335-6677 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Thailand’s Phalang Pracharat Party is a “junta party” established as a proxy for the 2014-2019 junta and the military, and specifically designed to sustain the power of the generals Prawit Wongsuwan, Prayut Chan-ocha and Anupong Paochinda. • Phalang Pracharat was created by the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC), and although it is extremely factionalized, having 20 cliques, it is nevertheless dominated by an Army faction headed by General Prawit Wongsuwan. • The party is financed by powerful corporations and by its intra-party faction leaders. • In 2021, Phalang Pracharat has become a model for other militaries in Southeast Asia intent on institutionalising their power. In Thailand itself, the party has become so well- entrenched that it will be a difficult task removing it from office. 2 ISSUE: 2021 No. -

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

The Two Faces of Thai Authoritarianism

East Asia Forum Economics, Politics and Public Policy in East Asia and the Pacific http://www.eastasiaforum.org The two faces of Thai authoritarianism 29th September, 2014 Author: Thitinan Pongsudhirak Thai politics has completed a dramatic turn from electoral authoritarianism under deposed premier Thaksin Shinawatra in 2001–2006 to a virtual military government under General Prayuth Chan-ocha. These two sides of the authoritarian coin, electoral and military, represent Thailand’s painful learning curve. The most daunting challenge for the country is not to choose one or the other but to create a hybrid that combines electoral sources of legitimacy for democratic rule and some measure of moral authority and integrity often lacked by elected officials. A decade ago, Thaksin was practically unchallenged in Thailand. He had earlier squeaked through an assets concealment trial on a narrow and questionable vote after nearly winning a majority in the January 2001 election. A consummate politician and former police officer, Thaksin benefited from extensive networks in business and the bureaucracy, including the police and army. In politics, his Thai Rak Thai party became a juggernaut. It devised a popular policy platform, featuring affordable universal healthcare, debt relief and microcredit schemes. It won over most of the rural electorate and even the majority of Bangkok. Absorbing smaller parties, Thai Rak Thai virtually monopolised party politics in view of a weak opposition. Thaksin penetrated and controlled supposedly independent agencies aimed at promoting accountability, particularly the Constitutional Court, the Election Commission and the Anti-Corruption Commission. His confidants and loyalists steered these agencies. His cousin became the army’s Commander-in-Chief. -

The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 6 The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Thai and U.S. Army Soldiers participate in Cobra Gold 2006, a combined annual joint training exercise involving the United States, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. Photo by Efren Lopez, U.S. Air Force The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics By Zachary Abuza Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 Series Editors: C. Nicholas Rostow and Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Thailand, July 2005

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Thailand, July 2005 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

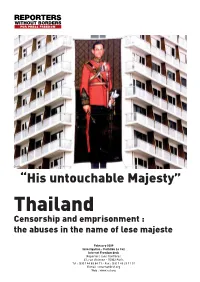

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

POLITICAL PARTY FINANCE REFORM and the RISE of DOMINANT PARTY in EMERGING DEMOCRACIES: a CASE STUDY of THAILAND by Thitikorn

POLITICAL PARTY FINANCE REFORM AND THE RISE OF DOMINANT PARTY IN EMERGING DEMOCRACIES: A CASE STUDY OF THAILAND By Thitikorn Sangkaew Submitted to Central European University - Private University Department of Political Science In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Supervisor: Associate Professor Matthijs Bogaards CEU eTD Collection Vienna, Austria 2021 ABSTRACT The dominant party system is a prominent phenomenon in emerging democracies. One and the same party continues to govern the country for a certain period through several consecutive multi-party elections. Literature on this subject has tended to focus on one (set) of explanation(s) deduced from electoral model, but the way a certain party dominates electoral politics at the outset of democratization remains neglected. Alternatively, this thesis highlights the importance of the party finance model, arguing that it can complement the understanding of one-party dominance. To evaluate this argument, the thesis adopts a complementary theories approach of the congruence analysis as its strategy. A systematic empirical analysis of the Thai Rak Thai party in Thailand provides support for the argument of the thesis. The research findings reveal that the party finance regime can negatively influence the party system. Instead of generating equitable party competition and leveling the playing field, it favors major parties while reduces the likelihood that smaller parties are more institutionalized and competed in elections. Moreover, the party finance regulations are not able to mitigate undue influence arising from business conglomerates. Consequently, in combination with electoral rules and party regulations, the party finance regime paves the way for the rise and consolidation of one- party dominance. -

CHAPTER 7 Thailand: Securitizing Domestic Politics

CHAPTER 7 Thailand: Securitizing Domestic Politics Thitinan Pongsudhirak Introduction Thailand’s second military coup in just eight years—this time on 22 May 2014— bears far-reaching ramifications for the country’s armed forces and defense sector. The military is once again triumphant and ascendant in Thai politics. It is as if Thailand’s political clock has been turned back to the 1960s-80s when the army dominated political life during a long stretch of military-authoritarian rule, punctuated by a short-lived democratic interval in the mid-1970s. The latest putsch came after six months of street demonstrations against the government of Yingluck Shinawatra, led by erstwhile Democrat Party senior executive, Suthep Thaugsuban. The street protests paralyzed central Bangkok and eventually paved the way for the coup, led by General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, then the army commander-in-chief. Since the coup, Thai politics has been eerily quiet, partly owing to the indefinite imposition of martial law and tight control on civil liberties and civil society activism. The ruling generals, under the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), immediately abolished the 2007 constitution, initially governing through military decrees before promulgating an interim constitution after two months. After that, it ascended a clutch of governing and legislative organs to rule, including the appointment of Gen. Prayuth as prime minister. This was the kind of hard coup and direct military-authoritarian rule Thailand has not seen in decades. But interestingly, the reactions to the coup both at home and abroad were mixed. Within Thailand, the forces belonging to former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, Yingluck’s deposed and self-exiled brother have not taken to the streets as anticipated. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Essential reading for anyone interested in ai politics and culture e ai monarchy today is usually presented as both guardian of tradition and the institution to bring modernity and progress to the ai people. It is moreover Saying the seen as protector of the nation. Scrutinizing that image, this volume reviews the fascinating history of the modern monarchy. It also analyses important cultural, historical, political, religious, and legal forces shaping Saying the Unsayable Unsayable the popular image of the monarchy and, in particular, of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. us, the book o ers valuable Monarchy and Democracy insights into the relationships between monarchy, religion and democracy in ailand – topics that, a er the in Thailand September 2006 coup d’état, gained renewed national and international interest. Addressing such contentious issues as ai-style democracy, lése majesté legislation, religious symbolism and politics, monarchical traditions, and the royal su ciency economy, the book will be of interest to a Edited by broad readership, also outside academia. Søren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager www.niaspress.dk Unsayable-pbk_cover.indd 1 25/06/2010 11:21 Saying the UnSayable Ivarsson_Prels_new.indd 1 30/06/2010 14:07 NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS STUDIES IN ASIAN TOPICS 32 Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) 33 Reaching for the Dream Melanie Beresford and Tran Ngoc Angie (eds) 34 Mongols from Country to City Ole Bruun and Li Naragoa (eds) 35 Four Masters of Chinese Storytelling -

Puangchon Unchanam ([email protected])

THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK GRADUATE SCHOOL AND UNIVERSITY CENTER Ph.D. Program in Political Science Student’s Name: Puangchon Unchanam ([email protected]) Dissertation Title: The Bourgeois Crown: Monarchy and Capitalism in Thailand, 1985-2014 Banner ID Number: 0000097211 Sponsor: Professor Corey Robin ([email protected]) Readers: Professor Susan Buck-Morss ([email protected]) Professor Vincent Boudreau ([email protected]) Abstract Most scholars believe that monarchy is irrelevant to capitalism. Once capitalism becomes a dominant mode of production in a state, the argument goes, monarchy is either abolished by the bourgeoisie or transformed into a constitutional monarchy, a symbolic institution that plays no role in the economic and political realms, which are exclusively reserved for the bourgeoisie. The monarchy of Thailand, however, fits neither of those two narratives. Under Thai capitalism, the Crown not only survives but also thrives politically and economically. What explains the political hegemony and economic success of the Thai monarchy? Examining the relationship between the transformation of the Thai monarchy’s public images in the mass media and the history of Thai capitalism, this study argues that the Crown has become a “bourgeois monarchy.” Embodying both royal glamour and middle-class ethics, the “bourgeois monarchy” in Thailand has been able to play an active role in the national economy and politics while secretly accumulating wealth because it provides a dualistic ideology that complements the historical development of Thai capitalism, an ideology that not only motivates the Thai bourgeoisie to work during times of economic growth but also tames bourgeois anxiety when economic crisis hits the country. -

'Thailand's Amazing 24 March 2019 Elections'

Contemporary Southeast Asia 41, No. 2 (2019), pp. 153–222 DOI: 10.1355/cs41-2a © 2019 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute ISSN 0129-797X print / ISSN 1793-284X electronic Anatomy: Future Backward DUNCAN McCARGO The most popular man in Thailand appears out of the bushes on Thammasat University campus, dripping with sweat and with no staff in sight: Future Forward leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit is promptly mobbed by fans clamouring for selfies and autographs. Voters on Bangkok’s Charoenkrung Road look delighted to see a former prime minister out on the campaign trail: eager to show off his fitness, Abhisit Vejjajiva practically runs up some footbridge steps, leaving the local candidate panting behind. A Pheu Thai candidate asks a village crowd in Ubon Ratchathani to raise their hands if they are better off now than they were five years ago: everyone roars with laughter at a woman who puts her hand up by mistake, since nobody could possibly be better off. In Pattani, thousands of people stay until midnight at a football ground to hear prominent speakers from the Prachachart Party. No big outdoor rallies like this have been held after dark in the three insurgency-affected southern border provinces since 2004. The weeks leading up to the 24 March 2019 elections were a time of excitement; after almost five years of military rule following the 22 May 2014 coup d’état, Thais were finally free to express themselves politically. Around 51 million people were eligible to vote, while a record total of 80 political parties and 13,310 candidates from across the ideological spectrum were listed on their ballot papers. -

Thailand's Political Cris

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trepo - Institutional Repository of Tampere University University of Tampere School of Management International Politics BREAKDOWN OF HEGEMONY IN THAILAND: THAILAND’S POLITICAL CRISIS 2006- IN GRAMSCIAN PERSPECTIVE Heli Kontio Pro Gradu –Thesis May 2014 UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT KONTIO, HELI: Breakdown of hegemony: Thailand’s political crisis 2006- in Gramscian perspective Pro Gradu – Thesis, 121 pages International Relations May 2014 ABSTRACT The central theme of this thesis is the proposal that in Thai politics, a new historical transformational phase, a new paradigm, has emerged since the 1997-98 Southeast Asian economic crises. It is proposed, that this new phase indicates the breakdown of the hegemonic rule of the old elite networks – the army, the bureaucracy, the palace, and the old Thai business elites. These networks, it is argued, have held both material and ideological control over the masses since Thailand became a modern capitalist state in the late 19th century during the historic hegemonic bloc of the Pax Britannica. The starting point for analysis in this study is to interpret Thailand’s current political crisis, which has been undergoing since the military ousted the Prime Minister elect, Taksin Shinawat, and his Thai Rak Thai government in September 2006, as a class conflict, the roots of which are embedded in the historical development processes of capitalism in Thailand. The new transformational phase, it is argued, indicates the emergence of the rural and the urban poor as a counter-hegemonic politically active social force in the realm of Thai politics.