Identities, Nations and Ethnicities: a Critical Comparative Study from Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Connection" in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries

AYUDHYA: CAPITAL-PORT OF SIAM AND ITS "CHINESE CONNECTION" IN THE FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES CHARNVIT KASETSIRI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY In 1990 Princess Maha Chakri presided over the open Ayudhya, founded in 1351, remained an important ing of the "Ayudhya Historical Study Centre," an elaborate economic and political center of Siam for more than four and gigantic research exhibition centre dedicated to the rich hundred years. In 1767 it was overrun by the Burmese, and diversity of Ayudhya history. The centre is a gift of¥ 999 the capital was rebuilt at Thonburi-Bangkok. Ayudhya is million from the Japanese Government to Thailand. It has situated about 90 kilometers from the coast, tucked away at two hi-tech exhibition buildings with one large room por the northern tip of the Gulf of Siam, making it some distance traying "Ayudhya as a port city. The exhibition depicts the away from the main international sea-route which passed the relationship between Ayudhya and foreign nations. A Thai straits between present-day Malaysia-Singapore-Indonesia. junk and Pomphet fort...[have been] recreated to demonstrate Strictly speaking, Ayudhya might be termed a hin the life-style, market places and trading activities of ancient terland kingdom. Its economy was self-sufficient, depending A yudhya," while another separate room displays a huge re on wet-rice cultivation and control of manpower. Overseas production of a map of Ayudhya drawn from a seventeenth trade seemed to be relatively small and less important, con century Dutch oil painting. sisting of exchanging raw natural products with manufac This room, "Ayudhya and its external relations," shows tured goods from more advanced countries-India, China, not only the impressive map but also documents for overseas and later Europe.1 Nevertheless, its overseas trade was a contact (i.e. -

Chao Phraya River Station C.2 Discharge Volume of 416 M3/Sec (Yesterday: 432 M3./Sec) Water Level: +19.33 M.M.S.L

Current Situation: normal, office hours 8.30 – 16.30 Water Watch and Monitoring System for Warning Center Royal Irrigation Department , MOAC Tel: 0 2669 2560 Fax 0 2243 6956, 0 2241 3350, 0 2243 1098 Hotline: 1460 http://www.rid.go.th/2009, http://wmsc.rid.go.th, E-mail : [email protected] th Report for water situation on 13 Sunday January 2013 1. Weather atmosphere The moderate high pressure covers upper Thailand causing cool with fog and dense fog in some places likely in the North, the Northeast and the Central. All transport should proceed with caution in areas of poor visibility. The southeasterly winds and the southerly winds prevail from the Gulf of Thailand with the humidity to the lower Central and the East resulting in isolated rain. 2. Highest rainfall in each region From 07.00 on 12th January 2013 to 07.00 on 13th January 2013 as follows: North part at Mueang Phchit 0.4 mm. Northeastern part at Mueang Kalasin 0.7 mm. Central part at Mueang Samut Prakan 5.8 mm. Eastern part at Ko Si Chang District Chon Buri 1.2 mm. Southern part (east coast) at Mueang Nakhon Si Thammarat 0.8 mm. Southern part (west coast) No rain 3. 3-day Raining Prediction During 14 – 17 January 2013, it is predicted that All regions may have rain about 1 – 5 mm. Information is from The National Centers for Environmental Prediction, starting prediction from 12th January 2013. 4. Water condition in reservoirs Water condition in large and medium scale reservoirs: Water volume in reservoir is 50,217 MCM which is 67% (available water volume is 26,418 MCM which is 35%). -

TIJBS FINAL VERSION.Indd 125 8/22/2011 4:11:43 PM 126 T� BS II, 2011 • Review

125 A Book Review: ‘Forest Recollections: Wandering Monks in Twentieth - Century Thailand’ Forest Recollections: Wondering Monks in Twentieth-Century Thailand. By Kamala Tiyavanich. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 1997. This book, published fourteen years ago, explains the life of Thai tudong or forest monks in the twentieth century. In general it is an accomplished account of forest monasticism in the North-East, explaining well the lifestyle of the monks, and the many physical and psychological problems they faced while living deep in the jungle. Important aspects of the forest life covered include how the forest tradition came into existence in Thailand (Chapter 1), how Thai monks take up the forest lifestyle and deal with problems of fear, bodily su ering, sexual desire, hardships of wandering and so on (Chapters 2-6), the monks’ relationship with Sangha o cials and villagers, and the con icts they had with the Sangha administration (Chapter 10). Thai International Journal of Buddhist Studies II (2011): 125-134. © The International PhD Programme in Buddhist Studies, Mahidol TIJBS FINAL VERSION.indd 125 8/22/2011 4:11:43 PM 126 T BS II, 2011 • Review The book begins with some background information, based especially on the work of previous scholars (especially J.L.Taylor)1 . Each chapter is arranged in a straightforward manner, with lucid explanations devoid of academic jargon, but with Thai or Laotian words in parentheses to help the general reader with local names. More problematic are the sections dealing with King Rama IV (King Mongkut, or former Vajiraño Bhikkhu) and Prince Vajirañavarorasa, his royal son. -

Chapter 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Introduction and Background in Today's Scenarios Tourism Industry Has Surpassed All Cliché Form

Chapter 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Introduction and Background In today’s scenarios tourism industry has surpassed all cliché forms of tourism and has reached to a new and innovative way to visit different places. In recent times tourists are getting highly influenced by the films and television programs in order to select their new place for travelling and this doesn’t happen with any tourism promotion strategies or campaigns but due to the films and television programs which show the images and videos of destinations. This concept can also be described as film-induced tourism in which the tourists choose destinations according to the attributes which they do see in films and television programs (Hudson & Ritchie, 2006). Gartner 1989; Echtner & Ritchie 1991) have also explained in this context images and sceneries in movies and TV programs play a very important role regarding the selection of place to visit and it helps in decision making process also. Chon 1990 in simpler ways explained that the more approving the image leads the higher chance of selecting the destination. Butler in 1990 also explained that films and television programs can impact on the travel inclination of those who reveal to the destinations characteristics and produce an affirmative destination image through their portrayal. Schofield 1996 indicated that films and television programs induced tourism to speedily become modish among audiences. Films and Television programs can offer great amount of knowledge of definite facets of the country or areas such as nature, culture, locations, events and people which can generate an interest towards the country and if the interest is positive and favorable which forefront to an actual visit to the country or the areas (Iswashita, 2006). -

Thailands Beaches and Islands

EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES & ISLANDS BEACHES • WATER SPORTS RAINFORESTS • TEMPLES FESTIVALS • WILDLIFE SCUBA DIVING • NATIONAL PARKS MARKETS • RESTAURANTS • HOTELS THE GUIDES THAT SHOW YOU WHAT OTHERS ONLY TELL YOU EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS MANAGING EDITOR Aruna Ghose SENIOR EDITORIAL MANAGER Savitha Kumar SENIOR DESIGN MANAGER Priyanka Thakur PROJECT DESIGNER Amisha Gupta EDITORS Smita Khanna Bajaj, Diya Kohli DESIGNER Shruti Bahl SENIOR CARTOGRAPHER Suresh Kumar Longtail tour boats at idyllic Hat CARTOGRAPHER Jasneet Arora Tham Phra Nang, Krabi DTP DESIGNERS Azeem Siddique, Rakesh Pal SENIOR PICTURE RESEARCH COORDINATOR Taiyaba Khatoon PICTURE RESEARCHER Sumita Khatwani CONTRIBUTORS Andrew Forbes, David Henley, Peter Holmshaw CONTENTS PHOTOGRAPHER David Henley HOW TO USE THIS ILLUSTRATORS Surat Kumar Mantoo, Arun Pottirayil GUIDE 6 Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound by L. Rex Printing Company Limited, China First American Edition, 2010 INTRODUCING 10 11 12 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 THAILAND’S Published in the United States by Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., BEACHES AND 375 Hudson Street, New York 10014 ISLANDS Copyright © 2010, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company DISCOVERING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND PAN-AMERICAN COPYRIGHT CONVENTIONS. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN THAILAND’S BEACHES A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, AND ISLANDS 10 ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER. Published in Great Britain by Dorling Kindersley Limited. PUTTING THAILAND’S A CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION RECORD IS BEACHES AND ISLANDS AVAILABLE FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. -

Sukhothai and Ayutthaya Pittayawat Pittayaporn1 Sireemas Maspong2 Shinnakrit Tangsiriwattanakul3 Yanyong Sikharit4

The genetic relationship between the Thai language of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya Pittayawat Pittayaporn1 Sireemas Maspong2 Shinnakrit Tangsiriwattanakul3 Yanyong Sikharit4 Chulalongkorn University1, 3, Cornell University2, Srinakharinwirot University4 Medieval Tai languages Kingdoms Oldest inscriptions Dates Sukhothai Bang Sanuk Inscription 1339 Tin Inscription of Ayutthaya Wat Maha That 1374 Lan Na Lan Thong Kham Inscription 1376 Lan Xang Nang An Inscription 14th century Sadiya Snake-Pillar Ahom 1497-1537 Inscription Bang Sanuk Inscription (1339) Tin Inscription of Wat Maha That (1374) Sukhothai and Ayutthaya 1238 AD The first king of Sukhothai King Sri Indraditya began the Phra Ruang Dynasty 1350 AD The first king of Ayutthaya King Ramathibodi I began the Uthong Dynasty 1438 AD Merger into Ayuthaya Kingdom 1767 AD The fall of Ayutthaya Kingdom Mother-Daughter or Cousins? Proto-Southwestern Tai Proto-Southwestern Tai Sukhothai Sukhothai Ayutthaya Ayutthaya Proposal • The Thai varieties attested in Sukhothai and Ayutthaya inscriptions are in fact the same language • Shared phonological innovations • Shared chronology Outline • Historical background • Previous phonological study of Sukhothai Thai (SKT) and Ayutthaya Thai (AYT) • Early phonological innovations • Later innovations • SKT-AYT as Old Thai Historical background Foundation of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya • SWT speakers must have arrived in present-day Thailand by the middle of the 12th century as attested by bas-reliefs in Angkor Wat (Coedès 1968; Phumisak 1976) • A coalition of Thai -

181228-ACT Opertor List.Xlsx

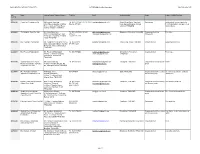

Organic Agriculture Certification Thailand (ACT) ACT-IFOAM Certified Operator Date: 28 December 2018 รหสั / Name Contact Person / Contact Address Tel & Fax Email Production Sites Scope Organic Certified Products Code No. 216 000142OC Green Net Cooperative Ltd. Ms.Boonjira Tanrueng Tel. 02-277 9380-1, 02-277 9653 [email protected] Kham Khuan Kaeo, Yasothorn, Processing rice products, coconut products, 6 Soi Piboon Uppatam- Wattana Fax. 02-277 9654 Huay-Kwang, Bangkok, Muang fresh food products and processed Nivej 7, Suthisarn Road, Huay- Chonburi THAILAND food products Kwang, Bangkok THAILAND 001844OC Thai Organic Food Co., Ltd. Mr. Kaan Ridkachorn Tel. 081-899 5289ม 02-641 [email protected],; Bangphae, Ratchaburi THAILAND Crop production and Fish sauce 976/17 Rimklongsamsen road, 5366-70, [email protected] Processing Bangkapi, Huaykwang, Bangkok Fax. 02-641 5365 10320 THAILAND 001944OC Ms. Piyaphan Phinthuphan Ms. Piyaphan Phinthuphan 29/166 Tel. 02-5034219, [email protected] Chaiyo, Ang Thong THAILAND Crop production vegetables and fruits Moo 9, Muangthongthani, Tambon 081-776-1238 Bangphud, Pakkred, Nonthaburi THAILAND 002244OC Ms. Pissamai Rattanapolti Ms. Pissamai Rattanapolti Tel. 085-7539004 [email protected]; Wichianburi, Petchaboon Crop production Field crops 49 Moo 1, Tambon Kokprong, [email protected] THAILAND Wichianburi, Petchaboon THAILAND 002644OC Organic Agriculture Project, Ms.Somjit Intapuang Tel. 088213 5023 [email protected]; Chiangmai, THAILAND Crop production and Grower Herbs Maetha Sustainable Agriculture 61 Moo 5 Tambon Maetha, Mae- [email protected] group Cooperative Co.,Ltd. On, Chiangmai 50130 THAILAND 002744OC Rice Fund Surin Organic Mr.Patipat Jamme, 087-2474685 [email protected] Surin, THAILAND Crop production, Processing rice, field crops and rice products Agriculture Cooperative, Ltd Mr.Arat Saengubon and Grower group (milled rice) 88 Moo 7, Tambon Kaeyai, Muang, Surin THAILAND 002944OC Nasoe Farmer Group Network Mrs. -

KING MONGKUT's POLITICAL and RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGIES THROUGH ARCIDTECTURE at PHRA NAKHON KIRI Somphong Amnuay-Ngerntra Abstract

KING MONGKUT'S Buddhist sect, Thammayut, is characterised as rational, intellectual, and POLITICAL AND humanistic. Such religious reform was RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGIES integrated with scientific knowledge, THROUGH which he had learned during his contact ARCIDTECTURE AT PHRA with Christian missionaries as a monk and later as king. NAKHON KIRI1 Introduction Somphong Amnuay-ngerntra 2 King Mongkut, through his long Abstract association with Christian rmss10naries while in the monkhood and on the throne, and the Siamese elite were aware of the This research investigates King Mongkut 's increasing threat of European colonisation vision of modernity as expressed through in Southeast Asia, particularly after the the medium of Phra Nakhon Kiri in British defeated the Burmese in 1837, and Phetchaburi. King Mongkut used when western firearms were used to settle hierarchically traditional architecture as the Opium War in China in 1842 (Batson, a means of bolstering national pride and 1984: 4). In response to global political legitimising claims to the right ofkingship . circumstances, the Siamese elite Simultaneously, a political position of introduced the concept of modernity and Siam as a modern state was manifested W esternisation to Siam by incorporating through European-Sino-Siamese hybrid Western ideas of governance and architectural styles in the mid-nineteenth administration, changing the economy to a century. In addition, the bell-shaped market, cash economy (Keyes, 1989: 45). pagoda style within the site complex Notably, these Siamese elite, who had reflected his religious reform directed at foreseen the potential benefits from the upgrading monastic practices and trade treaty, welcomed the British purifying the canon. His reformed demands and later signed commercial treaties with European countries beginning 1 This essay is a revised version of the paper with Britain in 1855. -

'We Love the King'

Honouring the Claim ‘We Love the King’ P. A. Payutto (Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya) Honouring the Claim ‘We Love the King’ by P. A. Payutto (Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya) translated by Robin Moore © 2016 Thai edition – สมเด則จพระพ稸ทธโฆษาจารย詌 (ป. อ. ปย稸ต嘺โต) © 2017 English edition – Robin Moore This book is available for free download at: www.watnyanaves.net Original Thai version first published: December 2016 Translated English version first published: March 2017 by Wat Nyanavesakavan and Peeranuch Kiatsommart Typeset in: Crimson, Gentium, Open Sans and TF Uthong. Cover design by: Phrakru Vinayadhorn (Chaiyos Buddhivaro) Layout design by: Supapong Areeprasertkul Printed by: Preface On the 13th October 2016 His Majesty Somdet Barom Raja Sambhara Somdet Phra Paramindra Maha Bhumibol Adulyadej King Rama IX passed away, causing great sorrow and grief for the Thai people across the entire country.1 Ever since the government first began allowing people the opportunity to pay respects to the royal remains, they have been thronging in large numbers to the palace day after day, without any noticeable decrease in numbers. The Thai people’s expressions of kind recollection and gratitude for His Majesty’s goodness and numerous royal initiatives performed over a long period of time for the wellbeing of his subjects is praiseworthy. Having said this, on this momentous occasion, the expression of gratitude (kataññū) should generate the additional fruit of repaying kindness (kataveditā) through earnest and resolute action. Thai people should be vigilant and committed to engaging in those actions answering to His Majesty’s royal pledge and fulfilling his heartfelt desire. By doing this the people themselves will improve their lives, cultivate virtue, and practise the Dhamma. -

The Interpretation of Si Satchanalai

THE INTERPRETATION OF SI SATCHANALAI By MR. Jaroonsak JARUDHIRANART A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism) International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2017 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย นายจรูญศกั ด์ิ จารุธีรนาท วทิ ยานิพนธ์น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรปรัชญาดุษฎีบณั ฑิต สาขาวิชาArchitectural Heritage Management and Tourism Plan 2.2 บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2560 ลิขสิทธ์ิของบณั ฑิตวทิ ยาลยั มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร THE INTERPRETATION OF SI SATCHANALAI By MR. Jaroonsak JARUDHIRANART A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism) International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2017 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University 4 Title THE INTERPRETATION OF SI SATCHANALAI By Jaroonsak JARUDHIRANART Field of Study (Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism) International Program Advisor Supot Chittasutthiyan Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair person ( Kreangkrai Kirdsiri , Ph.D.) Advisor ( Supot Chittasutthiyan , Ph.D.) External Examiner (Professor Emeritus ORNSIRI PANIN ) D ABST RACT 53056954 : Major (Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism) International Program Keyword : Si -

Reflecting on Agency in Traditional Central Thai Mural Painting

The Chinese Rabbit Seller and Other (Extra)Ordinary Persons: Reflecting on Agency in Traditional Central Thai Mural Painting Irving Chan Johnson National University of Singapore Abstract—This article explores the often overlooked images of ordinariness one finds in Thai temple mural painting. Through redirecting the scholarly gaze away from more traditional concerns with narrative, style and function, I show how seemingly banal scenes of the everyday are sites through which to locate subjective understandings of cultural and political identities. I do this by critically reflecting on my own work as a Thai mural painter in Singapore and showing how my situation within a diasporic Thai ritual universe transforms visual representations of Buddhist texts into fascinating engagements with the extraordinary, thereby inserting agency into a genre where artistic presence and viewership is largely silent. Once upon a time in the citadel of Paranasi (present-day Varanasi), the Buddha-to-be (phothisat) was born as a prince named Temi.1 Paranasi’s massive palace with its elegant spires, gabled roofs, thick walls and lacquered wood windows resembled the finest royal architecture found in central Siam.2 Outside the city walls, far from the musings of court life and reserved decorum, a Chinese man sold rabbits.3 His canvas shoes, bamboo hat, long-sleeved shirt and baggy trousers distinguished him from the city’s ethnic Thai residents. His hair flowed down his back in a neat queue, its sinuous form resembling that of the “flowing tail” pattern lai( hang lai) commonly seen in traditional Thai motifs. The rabbits attracted a little boy, who squatted in front of the furry creatures, perhaps in anticipation of taking one home. -

The Unmasking of Burmese Myth in Contemporary Thai Cinema

MEDIA@LSE MSc Dissertation Series Compiled by Bart Cammaerts, Nick Anstead and Ruth Garland The Unmasking of Burmese Myth in Contemporary Thai Cinema Pimtong Boonyapataro, MSc in Media and Communication Other dissertations of the series are available online here: http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/mediaWorkingPapers/ElectronicMScDissertatio nSeries.aspx Dissertation submitted to the Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, August 2015, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc in Media, and Communication. Supervised by Dr. Shakuntala Banaji The Author can be contacted at: [email protected] Published by Media@LSE, London School of Economics and Political Science (‘LSE’), Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. The LSE is a School of the University of London. It is a Charity and is incorporated in England as a company limited by guarantee under the Companies Act (Reg number 70527). Copyright, Pimtong Boonyapataro © 2015. The authors have asserted their moral rights. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. In the interests of providing a free flow of debate, views expressed in this dissertation are not necessarily those of the compilers or the LSE. MSc Dissertation of Pimtong Boonyapataro The Unmasking of Burmese Myth in Contemporary Thai Cinema Pimtong Boonyapataro ABSTRACT This empirical research attempts to deconstruct the representation of Burmese in contemporary Thai cinema, and to understand how the Thai cinematic portrayal of Burmese relates to the Thai sense of national identity.