Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Self-Powered Weigh-In- Motion System

Development of a Self-Powered Weigh-in- Motion System Project No. 19ITSUTSA01 Lead University: University of Texas at San Antonio Final Report December 2020 Disclaimer The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated in the interest of information exchange. The report is funded, partially or entirely, by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program. However, the U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the support by the Transportation Consortium of South- Central States (TranSET) i TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Project No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. 19ITSUTSA01 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Dec. 2020 Development of a Self-Powered Weigh-in-Motion System 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. PI: A.T. Papagiannakis https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3047-7112 Co-PI: Sara Ahmed https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0935-5011 Co-PI: Samer Dessouky https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6799-6805 GRA: Reza Khalili https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8383-4945 GRA: Gopal Vishwakarma https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5440-9149 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Transportation Consortium of South-Central States (Tran-SET) University Transportation Center for Region 6 11. Contract or Grant No. 3319 Patrick F. Taylor Hall, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 69A3551747106 LA 70803 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. -

One Stop | Directories | Search U of M View All Past Issues of Brief Vol

Return to: University Relations : U of M Home One Stop | Directories | Search U of M View all past issues of Brief Vol. XXXI No. 1 • January 10, 2001 Editor: Pauline Oo, 612-624-7889, [email protected] Past issues President Yudof talked about "special aspects that differentiate the U" from other state higher education institutions to House Higher Education Committee Jan. 8. Discussion included funding sources, expenditures, and enrollment and employment statistics. Presentation is available at www.umn.edu/govrel. Presentation to Senate Higher Education Budget Division will be Jan. 22, 1 p.m., State Capitol. President-elect Bush has named Yudof to his 31-member transition advisory committee on education. "Education policy and reform are longtime interests of mine," said Yudof, "and I look forward to discussing these critical issues with those charged with setting our nation's policies." Bush has named 475 individuals, including Minnesotans Yudof and Gov. Ventura, to work on 15 committees. Provost Bruininks has been appointed to Governor's Workforce Development Council. Group advises governor on workforce development policies and plans strategies associated with Minnesota's workforce. Recent gift of $10 million to Minnesota Landscape Arboretum is largest in its 42-year history. Arboretum, part of the Department of Horticultural Science, will use the gift from an anonymous donor to build new Visitor Center. Center will serve as formal entry point to gardens and collections; projected opening is 2004. Preliminary findings on unauthorized use of U long-distance telephone access code by 13 Gopher football student-athletes and other U students were released Dec. 20. -

H, SAY Plied, Sternly

B uchanan Record. PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY ---- »Y---- ID. ZBL. B O W E B . TERMS Sl.OO PER YEAR PATASLS IX ADYASOT. BELLS NEWS, IU , SCB3CKIPTIOXS DISCONTINUED AT EXPIRATION. SELLS BOOKS, ADVERTISING RATES. VOLUME XXXI, BLCHAXAX, BEERIEX COUNTY, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21, 1S97, NUMBER 39. LESS THAU ONE YEAR. One week........................... S -SO pet incA SELLS GUM* One month. ............ .90 “ Two m onths....... .......... 1.50 “ “ iVe- are all friends,” the man said Three m onths......................... 2.10 ‘ ‘ fiY.Yn’mfkY.Y again, as his head reached below the asked Zfaeltson, in derisive tones. j melange Six montha......................... S.40 “ HUMPHREYS’ level of the floor. Dim though the light MICHIGAS . YEARLY CONTRACTS. I “By denouncing' you,” Mr. Slorley re was upon the stairs, I recognized him One inch, $6.00 foe year o£ 5i Insertions. N o. 1 Cures Fever. A CLEW BY WIRE H, SAY plied, sternly. NEWS OF GENERA'- INTEREST TO OUR Two inches or over, $5.00 per inch, for year of « immediately, and with a loud call N o. 2 W o r m ', 5S insertions. Or, An Interrupted Current. j “Now, that is useless and foolish talk. sprang toward him. READERS. One column, $120 for year of 52 insertions. te N o. S Infants’ Diseases. Bet us reason, as between tw o business “Afr. Perry! Oh, thank God, you Celebrated Sleeping Car Magnate W on ’t you come to t t men,” said Jackson, assuming a confi > PP lr B—In Record Buildine.Oak Street N o. 4 Diarrhea. BY HOWARD M. YOST. have come!” I stepped unthinkingly Important Happenings in the State Daring Is No More. -

British Troops in Londonderry a Toast to Three Men Who Left Sky Unlimited

* N '. ' a ^ PAGE THIRTY’-SIX ' ■■ ' ‘ \ llanrbfHtpr €t>ratng iii^raib WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 18, 1969 Most Manchester Stores Open Tonight Until 9 O^Clock will be borne by the town, prin Town^ T ravelers Research cipally by in-kind services. Harkins, following the sign Av«rage Daily Net Press Run ing of the contract with Trav Sign C-DAP Study Contract elers, said that work on the Fbr nSe Week Ended The Weather C-DAP study will start im June M, IMS ^ J / contract waa signed In Harkins added, however, that mediately. Fair and mild .tonight with // tford txiday (or the services he anticipates that 'Travelers lows in the 60s. Tomorrow, / ■ of ^y^elers Research Corp., to will do a good job and that he 15,459 again, (air and warm with does not anticipate any need highs in upper 80s. be the o<™ultant for Manches Five-Day Forecast for cancellation WINDSOR LOCKS, Conn. Manchester— A City of Vitiate Charm ter’s two^ar C-DAP (Com C-DAP, which can be com (AP) — Temperatures In Con VOL. LXXXV m , NO. 268 munity DevfelQpment Action pared to jet^massive Comprehen necticut from ’Thursday through TWENTY-TWO PAGES MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, AUGUST 14, 1969 (CSaaatfted Ads-ertising on Ftage 19) PRICE TEN CENTS Plan) study. sive P,lah, is a two-year study Monday are expected to average Signing for the tmVh was Ly ot a town’s exlstlng/servlces near normal with daytime highs man Hoops, chalrmaiAof Man and facilities and a ^'projection from 80 to 86 and overnight chester’s C-DAP AgencjAx^l^ of its needs in the five-year lows in the 60s. -

![The American Legion Magazine [Volume 87, No. 5 (November 1969)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5937/the-american-legion-magazine-volume-87-no-5-november-1969-2055937.webp)

The American Legion Magazine [Volume 87, No. 5 (November 1969)]

THE AMERICAN 20C.N0VEMBER1969 LEGIONMAGAZINE The Growing Problems of AUTO DEFECTS AND REPAIRS — aris 10 Faimkm French PERFUMES ^^^^^ 10 world famous fragrances ^4.95 PARISIAN A SCENT FOR EVERY MOOD An extravagant, exciting gift at an unbelievably low price. Each in its own distinctive bottle and set You save when buying gift package of 10. in a beautiful tri-color gift box decorated $10.00 Our price, $1.50 for each bottle if bought separately. with gay, crisp drawings of Paris. These are all genuine full strength perfumes, We have imported a limited number of not toilet water or cologrie. these exciting gift packages for distribu- All perfumes sealed in the beautiful bottles you see pictured here. tion in the United States and Canada. Please rush your order now while the MOIMEY BACK C3UARAIMTEE supply lasts. Upon receipt of your order Niresk Importers, Dept. PR-132 we will rush this amazing gift package of 210 S. DesPlaines St., Chicago, HI. 60606 10 world famous French fragrances, each Please rush at once the fabulous collection of 10 World Famous Fragrance perfumes for only $4.95 each set plus for postage, handling and in its own different, distinctive bottle — 25C insurance—on full money-back guarantee. all for only $4.95. must You be completely I enclose $_ delighted or your money back promptly. Ship C.O.D. plus postage & C.O.D. fees. Charge to my Diners' Club Acct. No Please do not delay. Mail the no-risk Charge to my American Express Acct. No.. coupon today while our supply lasts. -

The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction

The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction Wood and WEST SYSTEM® Materials 5th Edition Meade Gougeon Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Bay City, Michigan Gougeon Brothers, Inc. P.O. Box 100 Patterson Avenue Bay City, Michigan, 48707-0908 Editor: Kay Harley Technical Editors: Brian K. Knight and Tom P. Pawlak Designer: Michael Barker Copyright © 2005, 1985, 1982, 1979 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. P.O. Box 908, Bay City, Michigan 48707, U. S. A. First edition, 1979. Fifth edition, 2005. Except for use in a review, no part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form, or by any means, electronic or manual, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system without prior written approval from Gougeon Brothers, Inc., P.O. Box 908, Bay City, Michigan 48707-0908, U. S. A., 866-937-8797 The techniques suggested in this book are based on many years of practical experience and have worked well in a wide range of applications. However, as Gougeon Brothers, Inc. and WEST SYSTEM, Inc.will have no control over actual fabrication, any user of these techniques should understand that use is at the user’s own risk. Users who purchase WEST SYSTEM® products should be careful to review each product’s specific instructions as to use and warranty provisions. LCCN 00000 ISBN 1-878207-50-4 Cover illustration by Michael Barker. Layout by Golden Graphics, Midland, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America by McKay Press, Inc., Midland, Michigan. Contents Preface . ix Acknowledgments . xi Chapter 1 Introduction–Gougeon Brothers and WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy . -

Captain Brown's House Historic Data

CAPTAIN BROWN'S HOUSE HISTORIC DATA Minute Man National Historical Park Concord, Massachusetts BY RICARDO TORRES-REYES DIVISION OF HISTORY Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation SEPTEMBER 29, 1969 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ii Captain DaTid Brown of Concord 1 Captain Brown's Homesite 1 Bibliography 12a .A.ppendix of Documents 13 S11JlllllU7' of DaTid Brown's Public Services 14 Ephrain Brown Inventory 18 Will and InYentory of Captain Brown 26 Letters from Captain Brown t• his children 33 Appendix of Maps 39 1 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report--RSP MM-H-35--is to acquire, interpret and prepare in useable form all available documentation about Captain David Brown's House. The report will be useful as a guide to archeological work, a source of information for inter pretation, and will document the historical base map. ii Captain David Brown of Concord David Brown, farmer, early patriot, and distinguished civic leader of Concord, was the son of Ephrain Brown and Hannah Wilson. He was born in 1732--the sixth of nine children--presumably in his father's old homesite near the Old Groton Road. 1 Young David was married to Abigail Munroe in 1756. She was probably of Concord also, and may have been a daughter of Thomas Munroe who had a large family of girls about David's age. He was described as a "tall, fine looking man, very kind-hearted and social in his feelings, well to do in matters of property, owning the farm on which he lived, then quite valuable, and carrying it on up to the time of his death."2 That Brown was a very active and prominent man in town affairs, before and after the Revolution, is attested by the Concord Town Records. -

Copyright by James Alan Therrell 2004

Copyright by James Alan Therrell 2004 The Dissertation Committee for James Alan Therrell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: IDEAS FROM A BALANCED “FAMILY”: THE FOUNDING AND PRACTICE OF A TEACHER COLLABORATION Committee: __________________________________ Stuart Reifel, Supervisor __________________________________ Elaine Fowler __________________________________ Norville Northcutt __________________________________ Anthony Petrosino __________________________________ David Schwarzer IDEAS FROM A BALANCED “FAMILY”: THE FOUNDING AND PRACTICE OF A TEACHER COLLABORATION by JAMES ALAN THERRELL, B.A., M.S. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN MAY, 2004 DEDICATION To those who, despite bearing the greater burden, provided the most support: my wife, Lan Huong, and my five-year-old, Vanessa Hoa. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No profound journey is ever trod without timely support from many sources. In my case there were many valued sources that, through working together in caring ways, helped to propel me, day by day, further down an arduous path toward this Ph.D. I first want to honor my family: for a mother who always told me, regardless of the challenge, “You can do it!” and for a father, though having passed away over twenty years ago, who was with me during the most difficult of times, lending me his will and his discipline to see the job through; and for two amazing siblings, who were both contributing advisors on the final manuscript: Jan, for her insights as a veteran school teacher and administrator, and Bob, for his critical thinking from an attorney’s point of view. -

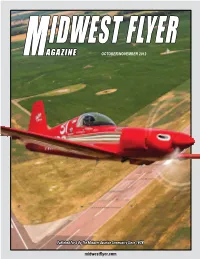

PDF Version October November 2012

IDWEST FLYER MAGAZINE OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2012 Published For & By The Midwest Aviation Community Since 1978 midwestflyer.com EA-SA_Ad Committed_MFM F.indd 1 9/30/11 1:12 PM EA-SA_Ad Committed_MFM F.indd 1 9/30/11 1:12 PM Vol. 34. No. 6 ContentsContents ISSN: 0194-5068 ON THE COVER: Richard (Dick) Keyt of Granbury, Texas, flying over Mitchell Municipal Airport, Mitchell, South Dakota, in his “Polen Special,” in preparation for the “AirVenture Cup Race,” August 22, 2012. The aircraft sports a fuel-injected Lycoming IO-360 engine and routinely flies at over 300 mph. This year the aircraft hit a top speed of 321.22 mph in the race. IDWEST FLYER Complete story beginning on page 37. Photo by Geoff Sobering of Moving-Target-Photos.com. OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2012 MAGAZINE HEADLINES Former EAA VP Named VP At AOPA ........................................................ 17 Leader In Piper Sales & Service, Howard Gregory, Passes Away ............ 18 Tanis Announces New President/CEO At AirVenture ................................ 30 Nation’s First Net Zero Energy Flight Terminal Breaks Ground At Outagamie County Regional Airport................................................... 32 WWII Veteran Donates Airport To Recreational Aviation Foundation For Future Generations .......................................................................... 36 Piper Celebrates 75th Anniversary At AirVenture ...................................... 41 HondaJet Design Recognized By AIAA...................................................... 42 Published For & By The Midwest -

Lls FS M8,Nl

Jt.TAb’ •1 i*7 Lls FS M8,Nl IF ‘, /5 /77/s/I (k L [5 ThTRO1XJCTIQi L; LHH L -: INNAHA Imriaha River in our Valley Has the nicest sort of clime Pray tell how to write Im-na-haw When Imntha doesn’t rhyme White faced cattle munchin bunch grass Poets call them critters Kine Have no worries on their faces Cause Imnaha doesn’t rhyme. Cowgirls dance with spurs a jinglin Swing your partners down the line Miss a step or two while prancin Imnaha still is not in rhyme. Rimrocks, canyons, gorges, eddies Master hands alone design Eras of the far off ages e Imnaha was to rhyme. Close your eyes and paint that picture Grieve the losses of the blind What they’d give to view the grandeur Of Imnaha without a rhyme. By: Joe Hopkins —--‘S PREFACE In writing this book of historical sketches of the Waflowa National Forest, the author makes no claim of literary merit. The story is developed from the authors personal knowledge and from the best known authorities available. The author believes that a knowledge of the early history of the Inland Enpire as it influenced the local area, of the Native American Inhabitants, and the struggles by which our ancestors took possession of this land, are necessary for an understanding of the prejudices and mores of our poople today. Therefor, several chapters have been devotec to the early period of exploration and settlement. It was decided to end the story of the Wallowa at the close of the year 1954. -

Appellate Craft

THE APPELLATE CRAFT by J. E. CÔTÉ A Justice of the Courts of Appeal of Alberta, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut The Canadian Judicial Council 2009 © Canadian Judicial Council Catalogue Number: JU14-20/2009 ISBN: 978-0-662-06475-6 Canadian Judicial Council Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1A 0N8 Telephone: (613) 288-1566 Fax: (613) 288-1575 Email: [email protected] Also available on the Council’s Web site at www.cjc-ccm.gc.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS | iii Table of Contents PREFACE . x CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION. 1 A. Who this Book is For . 1 B. Art, Science, or Craft?. 2 C. Approach or Philosophy . 3 CHAPTER 2 – MAKING LAW . 4 A. Two Functions of Courts of Appeal . 4 B. Stare Decisis. 6 C. Clarity of Precedents . 8 D. Natural Justice. 8 E. Overextended Law-Making? . 9 1. Introduction . 9 2. Judges Make Law . 9 3. Proper Degree. 10 4. Method Matters . 10 F. Afterword . 12 CHAPTER 3 – JUSTICE BETWEEN PARTIES . 13 A. Over-Legislating. 13 B. Written Reasoning. 18 C. Standards of Review . 18 1. Introduction. 18 2. Importance and Rationale . 19 3. Problems of Second Appeals . 19 D. Factual Appeals . 20 1. What is Palpable and Overriding Error . 20 (a) Skipped Factual Issue . 20 (b) Contradictory Findings . 20 (c) No Evidence at All. 21 (d) Evidence Misquoted . 21 (e) Logical Errors . 21 2. How to Research and Analyze the Evidence. 22 3. Trial Judge’s Failure to Find Facts . 23 E. New Trials . 23 1. Unfair Surprise . 24 2. Unequal Procedure . 24 3. Breach of Procedural Rules . -

Advanced Technologies & Innovations in Tourism & Hospitality Industry

Advanced Technologies & Innovations in Tourism & Hospitality Industry Volume-2 Editors: Dr. Shiv Mohan Verma, Mr. Sunil Kumar Pawar Mr. Indraneel Bose Bhikaji Cama Subharti College of Hotel Management Swami Vivekanand Subharti University, Meerut, U.P. Swaranjali Publication Pvt. Ltd. E-mail : [email protected] www.swaranjalipublication.com Sector 10-B, Vasundhara, Ghaziabad, (U.P.) 201012 Phone : 9810749840, 8700124880 Advanced Technologies & Innovations in Tourism & Hospitality Industry i All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder. © Editor : Dr. Shiv Mohan Verma : Mr. Sunil Kumar Pawar : Mr. Indraneel Bose Publisher : Swaranjali Publication Sector 10-B, Vasundhara, Ghaziabad, (U.P.) 201012 Phone : 9810749840, 8700124880 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.swaranjalipublication.com Edition : 2019 ISBN : 978-81-94364-28-3 Price : 1200/- Printed By : Swaranjali Offset Printers ii Advanced Technologies & Innovations in Tourism & Hospitality Industry preface For sustainable development and effective management of all related aspects of hospitality and tourism, it is essential to learn from the best practices around the world and be innovative in finding practical solutions to ever-evolving challenges. Innovative approaches should be taken to strategically align with the visions and expectation of key tourism & hospitality industry stakeholders in planning, developing, marketing, managing, monitoring and controlling. As we advocate that industry leaders and researchers should collaborate in seeking practical and innovative solutions for the challenges in hospitality and tourism, papers jointly written by industry leaders and academics are sought for this conference.