Grain Distribution and the Emergence of Popular Institutions in Medieval Genoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Tutto Il Fascicolo In

BOLLETTINO TRIMESTRALE, OMAGGIO AI SOCI - SPED. IN A.P. - 45% - ART. 2 COMMA 20/B LEGGE 662/96 - GENOVA Anno LIII, N.S. - N. 1 - Gennaio - Marzo 2021 Iscr. R.O.C. n. 25807 - Tariffa R.O.C.: “Poste Italiane S.p.A. - Sped. in Abb.to Postale - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1 comma 1, DCB Genova” sito internet: www.acompagna.org - [email protected] - tel. 010 2469925 in questo numero: Franco Bampi Almiro Ramberti Ghe l’emmo fæta! p. 1 Lampi sul mare una tranquilla domenica di guerra a Genova p. 26 Relaçion morale pe l’anno 2019 » 2 Premi e menzioni speciali 2021: bando e regolamento » 31 Silvana Raiteri Maria Cristina Ferraro Riflessioni su Genova, Santa Sofia Un ottimo esempio di istruzione professionale: la Scuola Apprendisti Interaziendale Ansaldo SIAC di Genova-Sestri » 32 e la grande moschea di Córdova » 5 Premi e menzioni speciali 2020 » 39 Piero Bordo A Carêga Do Diâo. La leggenda di Mordiroccia » 8 Occasioni per ricordare centenari cinquantenari del 2021 » 40 Francesca Di Caprio Francia Patrizia Risso Galleria di donne liguri, storie del passato » 12 Odone, il Savoia che amava Genova » 41 Marco Corzetto Isabella Descalzo Se possedessi una macchina del tempo... » 16 A Croxe de San Zòrzo » 46 Libbri riçevui » 48 Armando Di Raimondo Maurizio Daccà Cavour e i camalli del porto di Genova » 20 Vitta do Sodalissio » 49 Giulio Derchi In Memoria di Franco Ghisalberti » 51 I vin de l’îzoa de Sàn Pê: O ligamme tra Zena e Carlofòrte o se consèrva in botiggia » 25 Grifonetti d’A Compagna » 51 GHE L’EMMO FÆTA! di Franco Bampi Gente, ghe l’emmo fæta! Sciben che o “Covi” o s’é dæto da fâ pe mettine i bacchi tra e reue e pe aroinâne e feste do Dênâ e do prinçipio de l’anno, niatri o Confeugo l’emmo fæto o mæximo. -

Ministero Per I Beni E Le Attività Culturali E Per Il Turismo Archivio Di Stato Di Genova

http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo Archivio di Stato di Genova Instructiones et relationes Inventario n. 11 Regesti a cura di Elena Capra, Giulia Mercuri, Roberta Scordamaglia Genova, settembre 2020, versione 1.1 - 1 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it ISTRUZIONI PER LA RICHIESTA DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nella richiesta occorre indicare il nome del fondo archivistico e il numero della busta: quello che nell’inventario è riportato in neretto. Ad esempio per consultare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. occorre richiedere ARCHIVIO SEGRETO 2707 C SUGGERIMENTI PER LA CITAZIONE DELLE UNITÀ ARCHIVISTICHE Nel citare la documentazione di questo fondo, ferme restando le norme adottate nella sede editoriale di destinazione dello scritto, sarà preferibile indicare la denominazione completa dell’istituto di conservazione e del fondo archivistico seguite dal numero della busta, da quello del documento e, se possibile, dall’intitolazione e dalla data. Ad esempio per citare 2707 C, 87 1510 marzo 20 Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia. Tipologia documentaria: Lettere credenziali. Autorità da cui l’atto è emanato: Consiglio degli Anziani. Località o ambito di pertinenza: Francia. Persone menzionate: Giovanni Battista Lasagna. è bene indicare: Archivio di Stato di Genova, Archivio Segreto, b. 2707 C, doc. 87 «Lettere credenziali a Giovanni Battista Lasagna, inviato in Francia» del 20 marzo 1510. - 2 - http://www.archiviodistatogenova.beniculturali.it SOMMARIO Nota archivistica p. -

ROLLI DAYS Palazzi, Ville E Giardini Genova, 28 - 29 Maggio 2016

ROLLI DAYS palazzi, ville e giardini Genova, 28 - 29 maggio 2016 I Palazzi dei Rolli, Patrimonio dell’Umanità UNESCO IL SISTEMA DEI PALAZZI DEI ROLLI I PALAZZI DEI ROLLI Nel 2016 ricorre il decennale del riconoscimento da parte dell’UNESCO del sito “Le Strade Nuove e il Sistema dei Palazzi dei Rolli” , conferito nel 2006. Per celebrare l’anniversario, Genova propone tre edizioni dei Rolli Days: ) o c 2-3 Aprile, 28-29 maggio, 15-16 ottobre n a i B 2016 marks the tenth anniversary of UNESCO’s recognition of "The Strade Nuove and the o z system of the Palazzi dei Rolli" as a World Heritage Site in 2006. z a l To celebrate this anniversary, Genoa will be putting on three editions of the Rolli Days in 2016: a P ( i April 2-3, May 28-29 and October 15-16 d l a m i r G Il sito UNESCO “Genova, le Strade nuove e il sistema dei palazzi dei Rolli” conserva spazi urbani unitari di epoca a c u tardo-rinascimentale e barocca, fiancheggiati da oltre cento palazzi di famiglie nobiliari cittadine. Le maggiori L o dimore, varie per forma e distribuzione, erano sorteggiate in liste ufficiali (rolli) per ospitare le visite di Stato. I palazzi, z z a spesso eretti su suolo declive, articolati in sequenza atrio-cortile-scalone-giardino e ricchi di decorazioni interne, l a P esprimono una singolare identità sociale ed economica che inaugura l’architettura urbana di età moderna in Europa. i d L’iscrizione nella Lista del Patrimonio Mondiale conferma l’eccezionale valore universale di un sito culturale che o n i merita di essere protetto per il bene dell’umanità intera. -

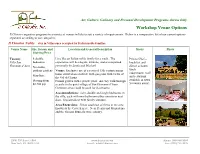

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Della Zecca Di Genova

GIOVANNI PESCE C O N T R IB U T O INEDITO AL «CORPVS NVMMORVM » DELLA ZECCA DI GENOVA Società Ligure di Storia Patria - biblioteca digitale - 2012 ' . ■ V.' . • ■ . • 1i 1 ; i 1 Società Ligure di Storia Patria - biblioteca digitale - 2012 ■ - Allorché nell’ormai lontano 1912 vide la luce il terzo volume del Corpus Num m orum Italicorum 1 contenente la descrizione delle monete della Liguria e della Corsica, molte opere sulla numismatica genovese erano già state pubblicate in epoca anteriore ed il Corpus stesso, nel pro cedere alla sistematica descrizione delle varie emissioni, ricorre con fre quenza a numerosi richiami attingendo notizie nella produzione pree sistente. Poche città italiane infatti possono vantare, al pari di Genova, una così cospicua e singolare mole di opere di interesse numismatico ad illu strazione della complessa attività di una zecca così importante che inizio a funzionare nel 1139 e provvide incessantemente a batter moneta fino alla caduta della Repubblica nel 1814. A parte il fondamentale studio del Desimoni2 che nel 1890 pubblicò in questi stessi atti le Tavole descrittive delle monete della zecca di Ge nova, merita in verità grande considerazione l’opera del Gandolfi3 che già nella prim a m età dell’Ottocento gettò le basi di uno studio tecnico-storico delle emissioni monetarie genovesi. Importante inoltre e del massimo in teresse il valido metodico contributo del Ruggero 4 con le famose Annota- 1 CORPUS NUMMORUM ITALICORUM. Primo tentativo di un catalogo ge nerale delle m onete medioevali e moderne coniate in Italia o da Italiani in altri paesi. Volume I I I : Liguria - Isola di Corsica. -

Bibliotheca Sacra

1901.] Conflict of Papacy and Empire. 491 ARTICLE V. THE FINAL CONFLICT OF THE PAPACY AND v THE MEDI£VAL EMPIRE. BY PROIlltSSOR DAVID S. SCHAFF, D. D. To the men of t<Hiay the half-century just passed seems to be one of the most wonderful eras in the world's history. Men of former generations have had this same feeling as they looked back over the events of their age. Writing of the first fifty years of the thirteenth century, Matthew Paris, a contemporary, says: "All these remarkable and strange events, the like of which have never been seen or heard of, nor are found in any writings of our fathers in times past, occurred during this last half-century." In this list of wonderful events, not a single invention or mechan ical discovery is adduced, and from the realm of nature only a few portents are mentioned. But, for all that, those fifty years do constitute a remarkable period. It was still the age of the Crusades, whose energies were, however, fast waning. It was the age of Francis d'Assisi and Dom inic, and the rise of the Mendicant Orders. It was the age of some of the greater Schoolmen. It was the age of Inno cent II!., whose eminence no occupant of the papal chair has ever surpassed, and few have equaled. It was the age of Runnymede and the Great Charter. Of the period, taken as a whole, the central figure was that very extraordinary personage, Frederick II., King of Sicily and Emperor of Germany. -

MICHAEL G. CORNELIUS Conradin, Hawking

EnterText 2.3 MICHAEL G. CORNELIUS Conradin, Hawking This is not a true history of the short and tragic life of Conradin of Sicily. Much of what I write here is found in chronicles of the day, and the information presented is to the best of my knowledge true, but I have taken some liberties, in accordance with the wants of my discourse. The different and various accounts of the short and undistinguished life of Conradin of Sicily agree on very little, save for the bare facts of his case. Was he held in a palace, as one modern historian asserts, or the same stinking dungeon as his Uncle Manfred’s family? Did he sleep at night beside his beloved in an opulent bed of silk and cherry wood, or on a pile of straw listening to the cries and screams of Beatrice, Manfred’s only daughter? We will never know. What is the value, anyway, of one singular life, of a footnote to the vast encyclopedia of history? Should we care about Conradin, about his love for Frederick of Baden, his unjust and cruel death at the hands of Anjou? Should we care about two men who share such a depth of love that one willingly joins the other on the scaffold, rather Michael G. Cornelius: Conradin, Hawking 74 EnterText 2.3 than be left alone? Or is this just another moment in history, largely unknown and forgotten? Perhaps Conradin’s life had no real value, or no more value than the life of any other man or woman. -

Download (10MB)

AVVERTENZA 11 lavoro, nato come inventario di un « fondo » dell Archivio di Stato geno vese a fini essenzialmente archivistici e non storici, risente di questa sua origine nella rigorosa limitazione dei regesti a quel fondo, pur ricostruito sulla base dell’ordine cronologico dei documenti, e nella sobrietà discreta dei singoli re gesti. Del pari la bibliografia non vuol essere un repertorio critico e non intende richiamare tutte le edizioni comunque eseguite dei diversi atti, ma limita i riferim enti alle edizioni principali, apparse nelle raccolte sistematiche più comu nem ente accessibili, ed a quanto fu pubblicalo del codice diplomatico dell Im periale. Si è ritenuta peraltro utile anche una serie di riferimenti agli Annali di Caffaro e Continuatori per i passi in cui si ricordano i fatti significati dai docum enti del fondo. Il lettore d’altra parte facilmente rileverà che tale appa rato si riferisce con larga prevalenza ai secoli del Medio Evo; il che rappresenta un fatto pieno di significato, anche se la serie dei richiami, come si è detto, e largamente incompleta. Gli indici, alla cui redazione ha direttamente collaborato, col dott. Liscian- drelli ed il dott. Costamagna, anche il Segretario prof. T.O. De Negri, che ha cu rato l’edizione, si riferiscono strettamente ai nomi riportati nei Regesti, ove spesso, per ovvie ragioni, i nominativi personali sono suppliti da richiami anoni mi o da titoli generici (re, pontefice1, imperatore...). Essi hanno quindi un valore indicativo di massima e non possono esaurire la serie dei riferimenti. Per m aggior chiarezza diamo di seguito, col richiamo alle sigle e nell or dine alfabetico delle sigle stesse, l’elenco delle pubblicazioni utilizzate. -

De Duarte Nunes De Leão

ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 CENTRO DE ESTUDOS EM LETRAS UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura (1576) de Duarte Nunes de Leão A ORTHOGRAPHIA DA LINGOA PORTVGVESA (1576) DE DUARTE NUNES DE LEÃO Orthographia da Lingoa Portvgvesa Orthographia A Estudo introdutório e edição Coelho, Fontes, Moura Coelho, Fontes, Assunção, Kemmler, Fernandes, Fernandes, Assunção, Kemmler, 2 VILA REAL - MMX I X Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura A ORTHOGRAPHIA DA LINGOA PORTVGVESA (1576) DE DUARTE NUNES DE LEÃO ESTUDO INTRODUTÓRIO E EDIÇÃO COLEÇÃO ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 CENTRO DE ESTUDOS EM LETRAS UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO VILA REAL • MMXIX Autores: Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura Título: A Orthographia da Lingoa Portvgvesa (1576) de Duarte Nunes de Leão: Estudo introdutório e edição Coleção: ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 Edição: Centro de Estudos em Letras / Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal ISBN: 978-989-704-388-8 e-ISBN: 978-989-704-389-5 Publicação: 27 de dezembro de 2019 Índice Prefácio ................................................................................................ V Estudo introdutório: 1 Duarte Nunes de Leão, o autor e a obra ................................................................ VII 1.1 Duarte Nunes de Leão (ca. 1530-1608): breve resenha biográfica ................................VII -

Procession in Renaissance Venice Effect of Ritual Procession on the Built Environment and the Citizens of Venice

Procession in Renaissance Venice Effect of Ritual Procession on the Built Environment and the Citizens of Venice Figure 1 | Antonio Joli, Procession in the Courtyard of the Ducal Palace, Venice, 1742. Oil on Canvas. National Gallery of Art Reproduced from National Gallery of Art, http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/Collection/art-object-page.32586.html Shreya Ghoshal Renaissance Architecture May 7, 2016 EXCERPT: RENAISSANCE ARCH RESEARCH PAPER 1 Excerpt from Procession in Renaissance Venice For Venetians, the miraculous rediscovery of Saint Mark’s body brought not only the reestablishment of a bond between the city and the Saint, but also a bond between the city’s residents, both by way of ritual procession.1 After his body’s recovery from Alexandria in 828 AD, Saint Mark’s influence on Venice became evident in the renaming of sacred and political spaces and rising participation in ritual processions by all citizens.2 Venetian society embraced Saint Mark as a cause for a fresh start, especially during the Renaissance period; a new style of architecture was established to better suit the extravagance of ritual processions celebrating the Saint. Saint Mark soon displaced all other saints as Venice’s symbol of independence and unity. Figure 2 | Detailed Map of Venice Reproduced from TourVideos, http://www.lahistoriaconmapas.com/atlas/italy-map/italy-map-venice.htm 1 Edward Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), 87. 2 Muir, Civic Ritual, 80-81. EXCERPT: RENAISSANCE ARCH RESEARCH PAPER 2 The Renaissance period in Venice, lasting through the Quattrocento and Cinquecento, was significant because of the city’s maintenance of civic peace; this was achieved in large part by the rise in number and importance of processional routes by the Doges, the elected leaders of the Republic.3 Venice proved their commitment to these processions by creating a grander urban fabric. -

VENICE Grant Allen's Historical Guides

GR KS ^.At ENICE W VENICE Grant Allen's Historical Guides // is proposed to issue the Guides of this Series in the following order :— Paris, Florence, Cities of Belgium, Venice, Munich, Cities of North Italy (Milan, Verona, Padua, Bologna, Ravenna), Dresden (with Nuremberg, etc.), Rome (Pagan and Christian), Cities of Northern France (Rouen, Amiens, Blois, Tours, Orleans). The following arc now ready:— PARIS. FLORENCE. CITIES OF BELGIUM. VENICE. Fcap. 8vo, price 3s. 6d. each net. Bound in Green Cloth with rounded corners to slip into the pocket. THE TIMES.—" Good work in the way of showing students the right manner of approaching the history of a great city. These useful little volumes." THE SCOTSMAN "Those who travel for the sake of culture will be well catered for in Mr. Grant Allen's new series of historical guides. There are few more satisfactory books for a student who wishes to dig out the Paris of the past from the im- mense superincumbent mass of coffee-houses, kiosks, fashionable hotels, and other temples of civilisation, beneath which it is now submerged. Florence is more easily dug up, as you have only to go into the picture galleries, or into the churches or museums, whither Mr. Allen's^ guide accordingly conducts you, and tells you what to look at if you want to understand the art treasures of the city. The books, in a word, explain rather than describe. Such books are wanted nowadays. The more sober- minded among tourists will be grateful to him for the skill with which the new series promises to minister to their needs." GRANT RICHARDS 9 Henrietta St.