How to Edit a Building: Fieldnotes from the North American Brasilia1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbus/Columbus

The Avery Review Sarah M. Hirschman – Columbus/Columbus Columbus, the debut feature film from artist Kogonada set in the unlikely Citation: Sarah M. Hirschman, “Columbus/ Columbus,” in the Avery Review 28 (December midcentury architecture mecca of Columbus, Indiana, was released to great 2017), http://averyreview.com/issues/28/columbus- acclaim this August and enjoyed a slow but celebrated rollout in independent columbus. theaters throughout the fall. [1] The pseudonymous filmmaker has been hailed for the originality of his voice and technique, in particular for the careful framing [1] Columbus is home to an exceptional quantity of midcentury buildings designed by architecture of architecture in his film. His use of deep, flat focus and wide shots foreground heavyweights. This is entirely thanks to a philanthropic the settings and distances viewers from the action of the actors. In this film, effort that began in 1957 by Cummins Corporation Chairman and hometown booster J. Irwin Miller that architecture has the presence normally afforded a central character. I saw provided funding for services on public buildings if the architects working on them were selected from Columbus in Columbus, Indiana, surrounded by a pumped-up hometown crowd a pre-approved short list. While Columbus has been eager to call themselves out as extras or to identify their cars as captured in well known within architecture circles (in 2012 it was the AIA’s “sixth most architecturally important city in parking lots. There was a conspiratorial air in the Yes Cinema, a nonprofit the country”), its location about fifty miles south of Indianapolis and its relatively rural setting have kept it art-house theater where Columbus was enjoying the theater’s highest-grossing under-visited and off the national radar. -

Preserving Historic Places

PRESERVING HISTORIC PLACES INDIANA’S STATEWIDE PRESERVATION CONFERENCE APRIL 17-20, 2018 COLUMBUS, INDIANA 2 #INPHP2018 WBreedingabash streetscape: Farm: Courtesy, courtesy Bartholomew Wabash County County Historical Historical Museum Society GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to Preserving Historic Places: Indiana’s Statewide Preservation Conference, 2018. We are excited to bring the annual conference for the first time to Columbus, which earned the moniker “Athens of the Prairie” in the 1960s for its world-class design and enlightened leadership. You’ll have a chance to see the city’s architecture—including nineteenth-century standouts and the Mid-Century Modern landmarks that have earned the city international renown. In educational sessions, workshops, and tours, you’ll discover the economic power of preservation, learn historic building maintenance tips, and much more, while meeting and swapping successes and lessons with others interested in preservation and community revitalization. LOCATION OF EVENTS CONTINUING EDUCATION You’ll find the registration desk and bookstore at First CREDITS Christian Church, 531 5th Street. Educational sessions take place at the church and Bartholomew County Public Library The conference offers continuing education credits (CEU) at 536 5th Street. Free parking is available in the church’s and Library Education Units (LEU) for certain sessions and lots on Lafayette Street and in the lot north of the Columbus workshops, with certification by the following organizations: Visitors Center in the 500 block of Franklin Street. Parking AIA Indiana is also available in the garage in the 400 block of Jackson American Planning Association Street. Street parking is free but limited to three hours. American Society of Landscape Architects, Indiana Chapter Indiana State Library BOOKSTORE Indiana Professional Licensing Agency for Realtors The Conference Bookstore, managed by the Indiana Historical Check the flyer in your registration bag for information on all Bureau, carries books on topics covered in educational sessions. -

LO 2019Cr Mill Race Marathon

MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS RUN&FUN // MILL RACE MARATHON 1 Proud sponsor: Our commitment to Columbus and Bartholomew County is strong. Offering 5 locations to serve you with full-service banking, insurance, investments, and 240 Jackson Street • 529 Washington Street 803 Washington Street • 1901 25th Street wealth advisory solutions, all 2310 W. Jonathan Moore Pike backed by a local team of (812)372-2265 • germanamerican.com financial professionals committed to customer service excellence. TR-35017766 MILL RACE MARATHON RUN&FUN OFFICIAL GUIDE to THE SEPTEMBER 27-28, 2019 2019 MILL Race Marathon PUBLISHER Bud Hunt EDITOR MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 Julie McClure 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 assistant YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS managing editor Kirk Johannesen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Anna Perlich ON THE COVER Participants are shown at the start of the 2018 Mill Race Marathon. Race organizers have planned one huge party in downtown Columbus, and you don't have to be a runner to participate. You'll find a health and fitness expo, live music, activities for kids, food and more. Use this as your guide to everything you need to know about the races and events. Then go run and have some fun! ©2019 by AIM Media Indiana. All rights reserved. Reproduction of stories, photographs and advertisements without permission is prohibited. INFO: 812-379-5633 TABLE OF CONTENTS Getting started Entertainment Welcome 4 Finish on Fourth map 24 Schedule -

LCF-Annualreport.Pdf

UTK Tower: Marshall Prado, 2018–19 UDRF Fellow Executive Summary The Columbus, Indiana community continues to demonstrate that the best way to have an authentically great place to live is through the process of working together with shared values and clear goals. Engaging excellent designers and relying upon a thoughtful process to build new buildings, landscapes, artworks, or reuse existing ones is a key part of our history. After more than seventy-five years, this tradition has created what we hold dear today: an internationally-recognized collection of architecture, art, and design that has become a defining characteristic of the community and the core of this city’s identity. Heritage Fund — The Community Foundation of Bartholomew County launched Landmark Columbus Foundation (LCF) in 2015 as one of its key programs to ensure that Columbus’ traditions and investments in design excellence are well cared for and can remain a source of inspiration for future generations. With the support of many in this community and those around the state and country, Heritage Fund’s program quickly became a community asset making a big difference through Exhibit Columbus and many progressive preservation efforts. 1 Executive Summary Bartholomew County Courthouse: Isaac Hodgson, 1874 In late 2019 Heritage Fund supported the move of this program to become a stand alone 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, with the mission to care for, celebrate, and advance the cultural heritage of Columbus, Indiana. At the start of 2020, the inaugural Board of Directors of LCF met to move the mission forward, and with dedicated staff, volunteers, and collaborators, this organization has made great progress and is poised for continued success far beyond today. -

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolatio

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolation Factory LA-Más People for Urban Progress PienZa Sostenible Christopher Battaglia BSU Daniel Luis Martinez and Etien Santiago IU Viola Ago OSU and Hans Tursack MIT Sean Lally UIC and Matthew Wizinsky UC Sean Ahlquist UM Marshall Prado UTK Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation Thirst 2019 2019 Exhibition J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize Good Design and the Community Presented by Cummins Inc. Exhibit Columbus is inspired by the 1986 exhibition, The J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize is the centerpiece Good Design and the Community: Columbus, Indiana, of Exhibit Columbus’ exhibition and symposium and created by the National Building Museum in Washington honors two great patrons of the Columbus community. when Columbus business leader and philanthropist The Miller Prize Recipients are international leaders that J. Irwin Miller became the first person inducted into were selected for their commitment to the transformative their Hall of Fame. power that architecture, art, and design has to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. With That exhibition honored the Miller family’s legacy of servant leadership and the entire city’s commitment to make Columbus the best community of its size. When profiled by this award, we bring these studios’ unique perspectives the Washington Post that year, Mr. Miller chose to emphasize the community’s process and involvement in building, rather than the architecture itself, as a source of his to Columbus to explore the traditions and values that hometown pride: “Architecture is something you can see. -

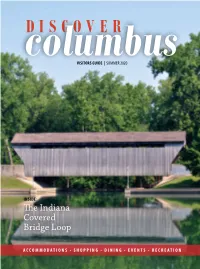

Columbusvisitors Guide | Summer 2020

DISCOVER columbusVISITORS GUIDE | summer 2020 INSIDE: The Indiana Covered Bridge Loop AccommodAtions • shopping • dining • events • recreAtion Summer 2020 | DISCOVER COLUMBUS 1 THANKS FOR LETTING US BE YOUR TRUSTED ADVISOR FOR THE PAST 45 YEARS! ADVERSITY REVEALS TRUE CHARACTER ■ Thanks to our clients, Kirr, Marbach celebrated its 45th Anniversary on May 1, 2020. ■ We were established in 1975 under a single goal: to be a friendly, knowledgeable, trustworthy and reassuring source of financial guidance to our clients. Our founding values remain: ◆ Loyalty. We act as fiduciaries to our clients. Our interests are aligned with yours. ◆ Humility. We don’t know what’s going to happen next, but we’ve navigated through numerous bull and bear markets, economic booms and busts, market bubbles and crashes and seen investment fads come and go. ◆ Discipline. We focus on the long-term voyage. ◆ Responsibility. We do what we say we’re going to do. ■ Visit our new website at www.kirrmar.com to view ◆ Our Insights page, which contains timely content on investments and personal finance we have both curated and created. ◆ A video featuring David Kirr, CFA discussing how he and Terry Marbach, CFA founded the firm after working for J. Irwin Miller at Irwin Management Company. ■ Whether you have $1,000 or $10 million to invest, we’d love to invest alongside you. Please contact us at (812) 376-9444 or by email so we can learn what matters to you. Zach Greiner Matt Kirr Maggie Kamman, CMA Assoc. Director of Client Service Director of Client Service Assoc. Director of Client Service [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TR-35045915 Registration of an investment advisor does not imply any level of skill or training. -

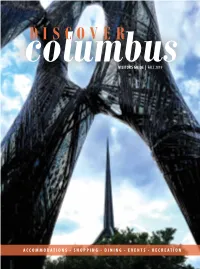

Columbusvisitors Guide | FALL 2019

DISCOVER columbusVISITORS GUIDE | FALL 2019 AccommodAtions • shopping • dining • events • recreAtion Fall 2019 | DISCOVER COLUMBUS 1 ‘unexpected and UNFORGETTABLE’ at one of our Award-Winning Hotels for business or leisure accommodations or meetings & special events. www.spraguehotels.com Columbus/Edinburgh Columbus/Edinburgh 812-526-8600 812-526-4919 Indianapolis South/ Greenwood Greenwood 317-881-0600 317-888-4814 Seymour 812-522-1200 Noblesville 317-316-0606 Columbus/Edinburgh 812-526-5100 Seymour 812-523-2409 Columbus/Edinburgh Fishers 812-526-9899 317-913-0300 Indianapolis South/ Coming Soon! Greenwood Indianapolis South/Greenwood 317-851-8518 All Columbus/Edinburgh locations are close to the Edinburgh Premium Outlet Mall. 2 DISCOVER COLUMBUS | Fall 2019 WELCOME ‘unexpected and UNFORGETTABLE’ Columbus is the county seat of Bartholomew County, where at one of our Midwest farming traditions have merged with modern manu- Award-Winning Hotels for facturing and service industries. Though located squarely in America’s heartland, Columbus is business or leisure accommodations truly an international city. People from all over the world call Columbus home. Currently 44 different native languages are or meetings & special events. spoken by students within the public school system. Much of the area’s ethnic diversity stems from the business www.spraguehotels.com community. More than 30 international companies from countries such as Japan, China, India, Germany, Korea and »Canada have facilities here. Cummins Inc., headquartered in Columbus, is a global company that brings many international employees to the community. Columbus/Edinburgh Columbus/Edinburgh We think the information on these pages will prove invaluable 812-526-8600 812-526-4919 to newcomers as they settle in to life in Columbus. -

The Future History of Public Art Symposium Proceedings

The Future History of Public Art Symposium Proceedings The 2017 Symposium of the Western States Arts Federation November 5-7, 2017 Honolulu, Hawai’i Symposium Director Lori Goldstein Symposium Advisors Jack Becker Karen Ewald Jonathan Johnson Jen Krava Anthony Radich Theresa Sweetland Proceedings Editors Lori Goldstein Laurel Sherman Contributing Editors Sonja K. Foss Lori Goldstein Cover Design Lori Goldstein Rainbows by Shige Yamada. Bronze. 1998. 11’6” x 4’ x 2’6” / 7’6”. University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Stan Sheriff Center. Photo Courtesy: Hawai’i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. For permission requests, please contact WESTAF (the Western States Arts Federation) at the address below: 2 WESTAF 1888 Sherman Street, Ste. 375 Denver, CO 80203 Phone: 303-629-1166 Fax: 303-629-9717 Email: [email protected] 3 Table of Contents About the Project Sponsors 8 Introduction 10 Symposium Participants 16 Presentations and Discussions Keynote Presentation 18 Our Inner Lives in Public: Making Space for Well-being and Kinship Candy Chang, Artist, New Orleans, Louisiana Welcome and Opening Remarks 30 • Anthony Radich, Executive Director, WESTAF, Denver, Colorado Moderator: ● Cameron Cartiere, Associate Professor, Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver, British Columbia The Future Democracy of Public Art 32 Presenters: • Jasper Wong, Founder and Lead Director, POW! WOW!, Honolulu, Hawai’i • Lauren Kennedy, Executive Director, UrbanArt Commission, Memphis, Tennessee • Larry Baza, Council Member, California Arts Council, San Diego, California -

Schedule of Events

Exhibit Columbus / DOCOMOMO-US / AIA Indiana & AIA Kentucky / Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (Design & Decorative Arts Department) REGISTER SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Wednesday 26 September The symposium begins in Indianapolis at Newfields. Join us for exclusive tours of the newly reinstalled design galleries at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, as well as the first reception and Evening Conversation of the symposium. All events on Wednesday take place in Indianapolis at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. 2:00-5:00 pm – Afternoon Tours at Newfields Design Gallery Tour 1 AIA LU|HSW The Indianapolis Museum of Art’s 11,000-square-foot Design Gallery is the largest collection gallery devoted to modern and contemporary design of any museum in the country. Join Shelley Selim, Associate Curator of Design and Decorative Arts, for a tour of the recently renovated gallery, now featuring a thematic reinterpretation that offers fresh insights into the versatile design process—from inspiration to production. A rotation of more than 150 new objects will be on display, many of which are recent acquisitions being shown for the first time. Newfields’ famed Miller House and Garden assumes a greater presence in the gallery with a fully immersive virtual reality experience. This joins several other new interactive spaces, including an 800-square-foot Design Lab where guests can design prototypes using analog and digital tools and try out some of the furniture on display. Participants will: Illustrate how the building meets certain universal design requirements for art museums. Observe the outcome of design strategies that were specific to the recent gallery renovation. -

The Miller House: Blue-Chip Midcentury Modernism in America’S Heartland

The Miller House: Blue-chip Midcentury Modernism in America’s Heartland Industrialist and architecture patron J. Irwin Miller commissioned a trio of designers—Eero Saarinen, Alexander Girard, and Dan Kiley—for his home in Indiana. It’s since been cemented in the canon as a masterpiece of midcentury residential design. By Kelsey Keith Updated Aug 29, 2019, 11:40am EDT Kelsey Keith Editor-in-chief Kelsey Keith first visited the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, back in 2011. She returned for another peek this summer, while in town for Exhibit Columbus, a biennial that activates public space as an entree to all the town’s architectural treasures. The original post has been updated throughout. American modernism is typified by three midcentury homes glorified in equal part by architecture geeks and tourists: Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater, Mies Page !1 of !9 Van Der Rohe's Farnsworth House, and Philip Johnson's Glass House. Since it opened as a house museum in 2011, another home in small town Columbus, Indiana, has been welcomed into that lofty club. The main entry to the Miller House. Legend has it that the Millers spotted these unusual pavers in Switzerland, couldn’t source anything like them in the United States, and so had them shipped to Indiana directly from Lausanne to pave their driveway. Kelsey Keith Designed by Eero Saarinen with interiors by Alexander Girard and landscaping by Dan Kiley, the Miller House was commissioned in 1953 by wealthy industrialist and modern architecture patron J. Irwin Miller and his wife Xenia. Among other feats (the house boasts what may be the world’s first conversation pit, for one), Miller House was the first National Historic Landmark to receive the honor while one of its designers was still living and while still occupied by its original owners. -

![Exhibit Columbus to Open August 23[3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3062/exhibit-columbus-to-open-august-23-3-6163062.webp)

Exhibit Columbus to Open August 23[3]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 21, 2019 Exhibit Columbus to open August 23 2019 exhibition brings together designers, academics, students, and volunteers to explore central theme of “Good Design and the Community” Exhibit Columbus, the annual exploration of architecture, art, design, and community, continues to celebrate the design legacy of Columbus, Indiana, with the opening of its second major exhibition this weekend, August 23-24, with two days of programming. The exhibition will feature 18 site-responsive installations by architects, designers, academics, artists, and graphic designers. These designers have created outdoor installations and experiences that use Columbus’ built heritage as inspiration and context, while highlighting the role that visionary community plays in growing a vibrant, sustainable, and equitable city. The exhibition is free and open to the public, and will transform downtown Columbus through December 1. For inspiration, Exhibit Columbus looked to the 1986 exhibition, Good Design and the Community: Columbus, Indiana, created when Columbus business leader and philanthropist J. Irwin Miller became the first person inducted into the National Building Museum Hall of Fame in Washington. Mr. Miller chose to emphasize the community’s process and involvement in building, rather than the architecture itself, as a source of his hometown pride: “Architecture is something you can see. You cannot see a spirit or a temperament or a character, though, and there’s an invisible part of this community of which I am very proud because, in a democracy, I think that the process is more important than the product.” Elaborating on the connection between the tangible and intangible culture that Mr. -

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype JOSHUA COGGESHALL Ball State University JANICE SHIMIZU Ball State University How can an architectural exhibition speak to ideas Lasch, Plan B Architecture & Urbanism, Oyler Wu Collaborative, of between-ness? How can a temporal event for- studio:indigenous, and IKD. ever transform the understanding of a place? In - Washington Street installations: Five international design gal- 2014, along with a small talented team, we started leries commissioned designers to add interventions that would working on a project with the goal to transform and connect emerging trends in design to the commercial core- Studio heighten awareness of the architectural legacy of Formafantasma, Pettersen & Hein, Productora, Cody Hoyt, and Columbus, Indiana, through the production of con- Snarkitecture temporary architecture and design. In this paper, we - University Installations: Six Midwest universities built prototypes will describe Exhibit Columbus’ curatorial premises beside Central Middle School and North Christian church- Ball State of dialogue and context through the lens of our mul- University, College of Architecture and Planning; The Ohio State tiple roles: as members of the steering committee University, Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture; University of that defined its curatorial vision, as university instal- Cincinnati, School of Architecture and Interior Design; University of lation coordinators who hope to impact architecture Kentucky, College of Design, School of Architecture; University of Michigan, Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, education in the Midwest, faculty research, and thoughts on pedagogy, and finally as instructor for - High School Installations: Local students did a design-build at the a design-build studio. historic post office.