Columbus/Columbus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

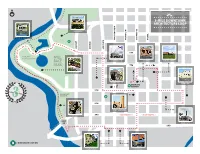

Three Mile Downtown Architecture Loop

EXIT 76 TOWN OF HOPE ANTIQUE MALL IUPUC COLUMBUS EDINBURGH MUNICIPAL AIRPORT PREMIUM OUTLETS ATTERBURY BAKALAR AIR MUSEUM 65 TAYLORSVILLE IVY TECH STATE RD. 9 RD. STATE SOCCER FIELDS CHAPMAN T. BLACKWELL III PARK FREEDOM FIELD PLAYGROUND 31 PAR 3 GOLF FLATROCK RIVER COURSE . - 31 31 9 NORTH H.S. FAIROAKS MALL APP. 3.5 MILES 46 LINCOLN PARK 9 46 DONNER PARK HOSPITAL NOBLITT PARK NOBLITT PARK 31 COUNTY RD. 650E RD. COUNTY CLIFTY CREEK ZAHARAKOS ICE CREAM PARLOR AND MUSEUM OTTER CREEK KIDSCOMMONS GOLF COURSE CHILDREN’S MUSEUM N F 3-MILE DOWNTOWN GREENBELT ARCHITECTURE LOOP GOLF COURSE FLATROCK RIVER MILL RACE COUNTY RD. 50N COVERED BRIDGE WASHINGTON FRANKLIN LAFAYETTE PEARL B LINDSEY BROWN JACKSON 8TH SUBJECT TO FLOODING MILL RACE CUMMINS H.Q. LIBRARY CENTRAL MIDDLE 31 PARK 7TH SAITOWITZ IRWIN CONF. CTR. PLANT ONE VISITORS EAST FORK, WHITE RIVER B CENTER DRIFTWOOD RIVER 5TH THREE-MILE RIDE LOOKOUT K;3 TOWER B CUMMINS INC. PLANT ONE 4TH 65 ELIEL SAARINEN 3RD < HIGH-TRAFFIC > < HIGH-TRAFFIC > SKOPOS 46 COUNTY RD. 100S HWY 4466 ST. PETER’S APP. 1.5 M. 2ND 46 B > BIKESHARE STATION 11 THE REPUBLIC CITY HALL EAST 4H FAIRGROUNDS HIGH CLIFTY CREEK 46 SCHOOL PARK HAW CREEK CERALAND EAST FORK WHITE RIVER 46 OGILVILLE LOUISVILLE REVISED MARCH 2010 SITES ALONG THE 3-MILE ARCHITECTURE LOOP (STARTING FROM THE VISITORS CENTER) CLEO ROGERS LIBRARY firms in the world and was named AIA Firm of the is a stop on The Indiana Covered Bridge Loop. The Architect : I.M. Pei, Pritzker Prize recipient | Pei also Year in both 1961 and again in 1996 - no other firm bridge is also, of course, a beautiful backdrop for designed Grand Louvre in Paris, and The Rock and has been awarded the prize more than once. -

Wright and Modernism in Indiana Indianapolis, Indiana May 1-3, 2015 Vis

Wright and Modernism in Indiana Indianapolis, Indiana May 1-3, 2015 VIS A Central Indiana holds a trove of architectural treasures. Some, like Frank PHOTO BY ANNE D Lloyd Wright’s Richard Davis House (1950) and John E. Christian Richard Davis House (Wright, 1950) House–Samara (1954) are tucked away in leafy enclaves, and some, like the midcentury modern wonders of Columbus, hide in plain sight. On the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy’s annual Out and About Wright tour, you’ll get to see both of Wright’s distinctive central Indiana works as well as several highlights around Indianapolis. Saturday, May 2 ERTIKOFF V We’ll depart from the Omni Severin Hotel starting at 8:30 a.m. to tour the local landmark Christian Theological Seminary (Edward Larrabee Barnes, 1966) and the 2012 AIA Honor Award-winning Ruth Lilly Visi- PHOTO BY ALEX tors Pavilion (Marlon Blackwell Architects, 2010) in the 100 Acres Art & John E. Christian House–Samara (Wright, 1954) Nature Park at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. After a brief stop at local icon The Pyramids (Roche Dinkeloo and Associates, 1967), we’ll head out to Wright’s Samara house in West Lafayette, a copper fascia-adorned Usonian still occupied by its original owner, and Davis House in Marion, with its unique 38-foot central octagonal teepee (we are one of the very few groups to tour this unique Wright work!). A seated lunch is included. We’ll return to the hotel around 6:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3 The list of architects with works in Columbus, Indiana reads like a who’s who of the great modernists: Saarinen, Pei, Weese, Pelli, Meier, Roche.. -

AIA Committee on Design Conference, Columbus, Indiana April 12-15, 2012: “Defining Architectural Design Excellence”

AIA Committee on Design conference, Columbus, Indiana April 12-15, 2012: “Defining Architectural Design Excellence” Last year Columbus, Indiana was rediscovered in the national media with the public opening of the Miller House and Gardens. An exquisite design collaboration of Eero Saarinen, Alexander Girard and Dan Kiley, completed in 1957, the landmark has been declared “America’s most significant modernist house”. While the house is now owned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) and public tours are available through the Columbus Visitors Center, the tours are often sold out, limited in numbers and access. The IMA is providing the AIA-COD the opportunity to visit the house and gardens as an “open house”, with guides distributed throughout to provide information, and is allowing us personal photography. If you have visited Columbus in the past, you are aware of its recognition for its many modern buildings designed by nationally and internationally recognized architects, including Eliel Saarinen, Eero Saarinen, Harry Weese, Robert Venturi, I.M. Pei, Gunnar Birkerts, Kevin Roche, and Richard Meier. Columbus has been called the “mecca of modern architecture” and “the Athens of the Prairie”. In 2000, in a highly unusual move, six modern architecture and landscape architecture sites were designated as National Historic Landmarks; including First Christian Church (Eliel Saarinen), Irwin Union Bank (Eero Saarinen), Miller House and Gardens, North Christian Church (Eero Saarinen), Mabel McDowell Elementary School (John Carl Warnecke), and First Baptist Church (Harry Weese). The AIA COD conference will visit each of these locations. The commitment to design excellence has continued in Columbus the last 10 years, in fact thriving to have had the most construction per capita through the Great Recession. -

Preserving Historic Places

PRESERVING HISTORIC PLACES INDIANA’S STATEWIDE PRESERVATION CONFERENCE APRIL 17-20, 2018 COLUMBUS, INDIANA 2 #INPHP2018 WBreedingabash streetscape: Farm: Courtesy, courtesy Bartholomew Wabash County County Historical Historical Museum Society GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to Preserving Historic Places: Indiana’s Statewide Preservation Conference, 2018. We are excited to bring the annual conference for the first time to Columbus, which earned the moniker “Athens of the Prairie” in the 1960s for its world-class design and enlightened leadership. You’ll have a chance to see the city’s architecture—including nineteenth-century standouts and the Mid-Century Modern landmarks that have earned the city international renown. In educational sessions, workshops, and tours, you’ll discover the economic power of preservation, learn historic building maintenance tips, and much more, while meeting and swapping successes and lessons with others interested in preservation and community revitalization. LOCATION OF EVENTS CONTINUING EDUCATION You’ll find the registration desk and bookstore at First CREDITS Christian Church, 531 5th Street. Educational sessions take place at the church and Bartholomew County Public Library The conference offers continuing education credits (CEU) at 536 5th Street. Free parking is available in the church’s and Library Education Units (LEU) for certain sessions and lots on Lafayette Street and in the lot north of the Columbus workshops, with certification by the following organizations: Visitors Center in the 500 block of Franklin Street. Parking AIA Indiana is also available in the garage in the 400 block of Jackson American Planning Association Street. Street parking is free but limited to three hours. American Society of Landscape Architects, Indiana Chapter Indiana State Library BOOKSTORE Indiana Professional Licensing Agency for Realtors The Conference Bookstore, managed by the Indiana Historical Check the flyer in your registration bag for information on all Bureau, carries books on topics covered in educational sessions. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Modernism in Bartholomew County, Indiana, from 1942

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MODERNISM IN BARTHOLOMEW COUNTY, INDIANA, FROM 1942 Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form E. STATEMENT OF HISTORIC CONTEXTS INTRODUCTION This National Historic Landmark Theme Study, entitled “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana from 1942,” is a revision of an earlier study, “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana, 1942-1999.” The initial documentation was completed in 1999 and endorsed by the Landmarks Committee at its April 2000 meeting. It led to the designation of six Bartholomew County buildings as National Historic Landmarks in 2000 and 2001 First Christian Church (Eliel Saarinen, 1942; NHL, 2001), the Irwin Union Bank and Trust (Eero Saarinen, 1954; NHL, 2000), the Miller House (Eero Saarinen, 1955; NHL, 2000), the Mabel McDowell School (John Carl Warnecke, 1960; NHL, 2001), North Christian Church (Eero Saarinen, 1964; NHL, 2000) and First Baptist Church (Harry Weese, 1965; NHL, 2000). No fewer than ninety-five other built works of architecture or landscape architecture by major American architects in Columbus and greater Bartholomew County were included in the study, plus many renovations and an extensive number of unbuilt projects. In 2007, a request to lengthen the period of significance for the theme study as it specifically relates to the registration requirements for properties, from 1965 to 1973, was accepted by the NHL program and the original study was revised to define a more natural cut-off date with regard to both Modern design trends and the pace of Bartholomew County’s cycles of new construction. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

LO 2019Cr Mill Race Marathon

MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS RUN&FUN // MILL RACE MARATHON 1 Proud sponsor: Our commitment to Columbus and Bartholomew County is strong. Offering 5 locations to serve you with full-service banking, insurance, investments, and 240 Jackson Street • 529 Washington Street 803 Washington Street • 1901 25th Street wealth advisory solutions, all 2310 W. Jonathan Moore Pike backed by a local team of (812)372-2265 • germanamerican.com financial professionals committed to customer service excellence. TR-35017766 MILL RACE MARATHON RUN&FUN OFFICIAL GUIDE to THE SEPTEMBER 27-28, 2019 2019 MILL Race Marathon PUBLISHER Bud Hunt EDITOR MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 Julie McClure 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 assistant YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS managing editor Kirk Johannesen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Anna Perlich ON THE COVER Participants are shown at the start of the 2018 Mill Race Marathon. Race organizers have planned one huge party in downtown Columbus, and you don't have to be a runner to participate. You'll find a health and fitness expo, live music, activities for kids, food and more. Use this as your guide to everything you need to know about the races and events. Then go run and have some fun! ©2019 by AIM Media Indiana. All rights reserved. Reproduction of stories, photographs and advertisements without permission is prohibited. INFO: 812-379-5633 TABLE OF CONTENTS Getting started Entertainment Welcome 4 Finish on Fourth map 24 Schedule -

LCF-Annualreport.Pdf

UTK Tower: Marshall Prado, 2018–19 UDRF Fellow Executive Summary The Columbus, Indiana community continues to demonstrate that the best way to have an authentically great place to live is through the process of working together with shared values and clear goals. Engaging excellent designers and relying upon a thoughtful process to build new buildings, landscapes, artworks, or reuse existing ones is a key part of our history. After more than seventy-five years, this tradition has created what we hold dear today: an internationally-recognized collection of architecture, art, and design that has become a defining characteristic of the community and the core of this city’s identity. Heritage Fund — The Community Foundation of Bartholomew County launched Landmark Columbus Foundation (LCF) in 2015 as one of its key programs to ensure that Columbus’ traditions and investments in design excellence are well cared for and can remain a source of inspiration for future generations. With the support of many in this community and those around the state and country, Heritage Fund’s program quickly became a community asset making a big difference through Exhibit Columbus and many progressive preservation efforts. 1 Executive Summary Bartholomew County Courthouse: Isaac Hodgson, 1874 In late 2019 Heritage Fund supported the move of this program to become a stand alone 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, with the mission to care for, celebrate, and advance the cultural heritage of Columbus, Indiana. At the start of 2020, the inaugural Board of Directors of LCF met to move the mission forward, and with dedicated staff, volunteers, and collaborators, this organization has made great progress and is poised for continued success far beyond today. -

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolatio

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolation Factory LA-Más People for Urban Progress PienZa Sostenible Christopher Battaglia BSU Daniel Luis Martinez and Etien Santiago IU Viola Ago OSU and Hans Tursack MIT Sean Lally UIC and Matthew Wizinsky UC Sean Ahlquist UM Marshall Prado UTK Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation Thirst 2019 2019 Exhibition J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize Good Design and the Community Presented by Cummins Inc. Exhibit Columbus is inspired by the 1986 exhibition, The J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize is the centerpiece Good Design and the Community: Columbus, Indiana, of Exhibit Columbus’ exhibition and symposium and created by the National Building Museum in Washington honors two great patrons of the Columbus community. when Columbus business leader and philanthropist The Miller Prize Recipients are international leaders that J. Irwin Miller became the first person inducted into were selected for their commitment to the transformative their Hall of Fame. power that architecture, art, and design has to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. With That exhibition honored the Miller family’s legacy of servant leadership and the entire city’s commitment to make Columbus the best community of its size. When profiled by this award, we bring these studios’ unique perspectives the Washington Post that year, Mr. Miller chose to emphasize the community’s process and involvement in building, rather than the architecture itself, as a source of his to Columbus to explore the traditions and values that hometown pride: “Architecture is something you can see. -

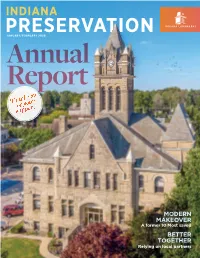

Modern Makeover Better Together

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2020 Annual Report MODERN MAKEOVER A former 10 Most saved BETTER TOGETHER Relying on local partners FROM THE PRESIDENT BY THE NUMBERS Temple Beth-El South Bend BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS Olon F. Dotson Muncie Hon. Randall T. Shepard Honorary Chairman Jeremy D. Efroymson Indianapolis Parker Beauchamp Better to Keep Her Chairman Melissa Glaze Roanoke James P. Fadely, Ph.D. people who attended Indiana ONE OF THE MOST JARRING entries in Indiana Landmarks’ Past Chairman Tracy Haddad Columbus Sara Edgerton Landmarks tours, talks, open current 10 Most Endangered list is the Pulaski County Vice Chairman David A. Haist Culver houses, and events around the Courthouse, a Romanesque Revival gem that imparts dignity Marsh Davis President Bob Jones Evansville state in the last year and grandeur to Winamac, the county seat. When we were Doris Anne Sadler Secretary/Assistant Treasurer Christine H. Keck Evansville alerted that Pulaski County officials were considering demo- Thomas H. Engle Assistant Secretary Matthew R. Mayol, AIA lition of their historic courthouse, our immediate response Indianapolis Brett D. McKamey might have been to raise a chorus of opposition and do battle Treasurer Ray Ontko Richmond with public officials. Instead, we committed to helping the Judy A. O’Bannon Secretary Emerita Martin E. Rahe congregations receiving training county find another path that might lead to the preservation Cincinnati, OH DIRECTORS James W. Renne in landmark stewardship, of the courthouse. Hilary Barnes Newburgh community engagement, and Indianapolis We can conjure compelling reasons for saving the court- George A. Rogge fundraising from Sacred Places The Rt. Rev. Jennifer Gary Riverside High School house: design, craftsmanship, materials, community char- Baskerville-Burrows Sallie W. -

Photographs of American Architecture and Architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Mss 302

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc11jp No online items Guide to the Photographs of American architecture and architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Mss 302 UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2013 Mss 302 1 Title: Photographs of American architecture and architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Identifier/Call Number: Mss 302 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 39.0 linear feet(94 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1936-1983 Abstract: American and European architectural images totaling four thousand one hundred and eighty-three images (4,183) two thirds of which are of American architecture and the rest European, with a small number of images from Mexico. Physical location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. General Physical Description note: (94 document boxes) Creator: Andrews, Wayne Access Use of the collection is unrestricted. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained.