When Was Columbus Modern? the Word “Modern,” According to Webster's Means “Of, Related To, Or Characteristic of the Pres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

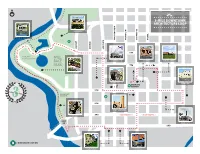

Three Mile Downtown Architecture Loop

EXIT 76 TOWN OF HOPE ANTIQUE MALL IUPUC COLUMBUS EDINBURGH MUNICIPAL AIRPORT PREMIUM OUTLETS ATTERBURY BAKALAR AIR MUSEUM 65 TAYLORSVILLE IVY TECH STATE RD. 9 RD. STATE SOCCER FIELDS CHAPMAN T. BLACKWELL III PARK FREEDOM FIELD PLAYGROUND 31 PAR 3 GOLF FLATROCK RIVER COURSE . - 31 31 9 NORTH H.S. FAIROAKS MALL APP. 3.5 MILES 46 LINCOLN PARK 9 46 DONNER PARK HOSPITAL NOBLITT PARK NOBLITT PARK 31 COUNTY RD. 650E RD. COUNTY CLIFTY CREEK ZAHARAKOS ICE CREAM PARLOR AND MUSEUM OTTER CREEK KIDSCOMMONS GOLF COURSE CHILDREN’S MUSEUM N F 3-MILE DOWNTOWN GREENBELT ARCHITECTURE LOOP GOLF COURSE FLATROCK RIVER MILL RACE COUNTY RD. 50N COVERED BRIDGE WASHINGTON FRANKLIN LAFAYETTE PEARL B LINDSEY BROWN JACKSON 8TH SUBJECT TO FLOODING MILL RACE CUMMINS H.Q. LIBRARY CENTRAL MIDDLE 31 PARK 7TH SAITOWITZ IRWIN CONF. CTR. PLANT ONE VISITORS EAST FORK, WHITE RIVER B CENTER DRIFTWOOD RIVER 5TH THREE-MILE RIDE LOOKOUT K;3 TOWER B CUMMINS INC. PLANT ONE 4TH 65 ELIEL SAARINEN 3RD < HIGH-TRAFFIC > < HIGH-TRAFFIC > SKOPOS 46 COUNTY RD. 100S HWY 4466 ST. PETER’S APP. 1.5 M. 2ND 46 B > BIKESHARE STATION 11 THE REPUBLIC CITY HALL EAST 4H FAIRGROUNDS HIGH CLIFTY CREEK 46 SCHOOL PARK HAW CREEK CERALAND EAST FORK WHITE RIVER 46 OGILVILLE LOUISVILLE REVISED MARCH 2010 SITES ALONG THE 3-MILE ARCHITECTURE LOOP (STARTING FROM THE VISITORS CENTER) CLEO ROGERS LIBRARY firms in the world and was named AIA Firm of the is a stop on The Indiana Covered Bridge Loop. The Architect : I.M. Pei, Pritzker Prize recipient | Pei also Year in both 1961 and again in 1996 - no other firm bridge is also, of course, a beautiful backdrop for designed Grand Louvre in Paris, and The Rock and has been awarded the prize more than once. -

Columbus/Columbus

The Avery Review Sarah M. Hirschman – Columbus/Columbus Columbus, the debut feature film from artist Kogonada set in the unlikely Citation: Sarah M. Hirschman, “Columbus/ Columbus,” in the Avery Review 28 (December midcentury architecture mecca of Columbus, Indiana, was released to great 2017), http://averyreview.com/issues/28/columbus- acclaim this August and enjoyed a slow but celebrated rollout in independent columbus. theaters throughout the fall. [1] The pseudonymous filmmaker has been hailed for the originality of his voice and technique, in particular for the careful framing [1] Columbus is home to an exceptional quantity of midcentury buildings designed by architecture of architecture in his film. His use of deep, flat focus and wide shots foreground heavyweights. This is entirely thanks to a philanthropic the settings and distances viewers from the action of the actors. In this film, effort that began in 1957 by Cummins Corporation Chairman and hometown booster J. Irwin Miller that architecture has the presence normally afforded a central character. I saw provided funding for services on public buildings if the architects working on them were selected from Columbus in Columbus, Indiana, surrounded by a pumped-up hometown crowd a pre-approved short list. While Columbus has been eager to call themselves out as extras or to identify their cars as captured in well known within architecture circles (in 2012 it was the AIA’s “sixth most architecturally important city in parking lots. There was a conspiratorial air in the Yes Cinema, a nonprofit the country”), its location about fifty miles south of Indianapolis and its relatively rural setting have kept it art-house theater where Columbus was enjoying the theater’s highest-grossing under-visited and off the national radar. -

Preserving Historic Places

PRESERVING HISTORIC PLACES INDIANA’S STATEWIDE PRESERVATION CONFERENCE APRIL 17-20, 2018 COLUMBUS, INDIANA 2 #INPHP2018 WBreedingabash streetscape: Farm: Courtesy, courtesy Bartholomew Wabash County County Historical Historical Museum Society GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to Preserving Historic Places: Indiana’s Statewide Preservation Conference, 2018. We are excited to bring the annual conference for the first time to Columbus, which earned the moniker “Athens of the Prairie” in the 1960s for its world-class design and enlightened leadership. You’ll have a chance to see the city’s architecture—including nineteenth-century standouts and the Mid-Century Modern landmarks that have earned the city international renown. In educational sessions, workshops, and tours, you’ll discover the economic power of preservation, learn historic building maintenance tips, and much more, while meeting and swapping successes and lessons with others interested in preservation and community revitalization. LOCATION OF EVENTS CONTINUING EDUCATION You’ll find the registration desk and bookstore at First CREDITS Christian Church, 531 5th Street. Educational sessions take place at the church and Bartholomew County Public Library The conference offers continuing education credits (CEU) at 536 5th Street. Free parking is available in the church’s and Library Education Units (LEU) for certain sessions and lots on Lafayette Street and in the lot north of the Columbus workshops, with certification by the following organizations: Visitors Center in the 500 block of Franklin Street. Parking AIA Indiana is also available in the garage in the 400 block of Jackson American Planning Association Street. Street parking is free but limited to three hours. American Society of Landscape Architects, Indiana Chapter Indiana State Library BOOKSTORE Indiana Professional Licensing Agency for Realtors The Conference Bookstore, managed by the Indiana Historical Check the flyer in your registration bag for information on all Bureau, carries books on topics covered in educational sessions. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolatio

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolation Factory LA-Más People for Urban Progress PienZa Sostenible Christopher Battaglia BSU Daniel Luis Martinez and Etien Santiago IU Viola Ago OSU and Hans Tursack MIT Sean Lally UIC and Matthew Wizinsky UC Sean Ahlquist UM Marshall Prado UTK Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation Thirst 2019 2019 Exhibition J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize Good Design and the Community Presented by Cummins Inc. Exhibit Columbus is inspired by the 1986 exhibition, The J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize is the centerpiece Good Design and the Community: Columbus, Indiana, of Exhibit Columbus’ exhibition and symposium and created by the National Building Museum in Washington honors two great patrons of the Columbus community. when Columbus business leader and philanthropist The Miller Prize Recipients are international leaders that J. Irwin Miller became the first person inducted into were selected for their commitment to the transformative their Hall of Fame. power that architecture, art, and design has to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. With That exhibition honored the Miller family’s legacy of servant leadership and the entire city’s commitment to make Columbus the best community of its size. When profiled by this award, we bring these studios’ unique perspectives the Washington Post that year, Mr. Miller chose to emphasize the community’s process and involvement in building, rather than the architecture itself, as a source of his to Columbus to explore the traditions and values that hometown pride: “Architecture is something you can see. -

P.E. Macallister Collection

Collection # P 0492 P. E. MACALLISTER COLLECTION 1974–2010 (DVDS, 1982–2007) Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Processed by Sarah Newell and Barbara Quigley June 12, 2012 Revised June 16, 2015 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 309 titles on DVD (1982–2007); 10 folders of manuscript and COLLECTION: printed materials (1974–2010) COLLECTION 1974–2010 (DVDs, 1982–2007) DATES: PROVENANCE: Donated by P.E. MacAllister, 2008; second accession in December 2008 of 94 DVDs of On Site programs (ca. 1983- 2006) from IUPUI special collections, who in turn got them from P.E. MacAllister; MacAllister Machinery newsletters mailed to IHS in 2010 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2008.0004, 2008.0380, 2010.0382X NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH P.E. (Pershing Edwin) MacAllister is chairman of the board at MacAllister Machinery Co., a Caterpillar dealership started by his father. He was born 30 August 1918 in Green Bay, Wisconsin, to Edwin W. and Hilda MacAllister. His father, a WWI veteran, named him Pershing after General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing. P.E. graduated from Carroll College in Waukesha, Wisconsin, with a major in history and minors in English and speech. Upon his graduation he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and reported for duty at the Muskogee, Oklahoma, Air Corps Primary Training School. -

Download a PDF of the FY19-20 Biennial Report

The arts everywhere every day for everyone in Indiana. Biennial Report Fiscal Years 2019–2020 We value you. To create equitable access to the arts for all Indiana residents, the Indiana Arts Commission is committed to intentional and ongoing engagement with all communities in our state. We will listen, engage, and incorporate diverse people and perspectives into all policies, programs, and services. Being consistently mindful and inclusive of the needs, ideas, and cultural history of the people who call Indiana home, we value and embrace their artistic expression and support them as they advance the arts that reflect their values and traditions. We believe in embracing diversity, championing inclusion, practicing equity, and embodying both the geographic and cultural variety that form the fabric of Indiana. What we do. We positively impact the cultural, economic and educational climate of Indiana by providing responsible leadership for and public stewardship of artistic resources for all of our state's citizens and communities. A look to the future. Good government starts with access for all citizens. The last two years have been exemplary for the Indiana Arts Commission as the agency has advanced its opportunities for artists, arts providing organizations and communities, and has helped our arts assets prosper, endure and ultimately pivot to engage and serve our citizens during an unprecedented pandemic. The demand for Arts Commission services has never been greater, with a record number of applicants to our granting programs and record participation in our education services. This helps our arts assets advance their abilities to produce public value by engaging with everyone, every day, everywhere in our state. -

The Future History of Public Art Symposium Proceedings

The Future History of Public Art Symposium Proceedings The 2017 Symposium of the Western States Arts Federation November 5-7, 2017 Honolulu, Hawai’i Symposium Director Lori Goldstein Symposium Advisors Jack Becker Karen Ewald Jonathan Johnson Jen Krava Anthony Radich Theresa Sweetland Proceedings Editors Lori Goldstein Laurel Sherman Contributing Editors Sonja K. Foss Lori Goldstein Cover Design Lori Goldstein Rainbows by Shige Yamada. Bronze. 1998. 11’6” x 4’ x 2’6” / 7’6”. University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Stan Sheriff Center. Photo Courtesy: Hawai’i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts. For permission requests, please contact WESTAF (the Western States Arts Federation) at the address below: 2 WESTAF 1888 Sherman Street, Ste. 375 Denver, CO 80203 Phone: 303-629-1166 Fax: 303-629-9717 Email: [email protected] 3 Table of Contents About the Project Sponsors 8 Introduction 10 Symposium Participants 16 Presentations and Discussions Keynote Presentation 18 Our Inner Lives in Public: Making Space for Well-being and Kinship Candy Chang, Artist, New Orleans, Louisiana Welcome and Opening Remarks 30 • Anthony Radich, Executive Director, WESTAF, Denver, Colorado Moderator: ● Cameron Cartiere, Associate Professor, Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver, British Columbia The Future Democracy of Public Art 32 Presenters: • Jasper Wong, Founder and Lead Director, POW! WOW!, Honolulu, Hawai’i • Lauren Kennedy, Executive Director, UrbanArt Commission, Memphis, Tennessee • Larry Baza, Council Member, California Arts Council, San Diego, California -

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype JOSHUA COGGESHALL Ball State University JANICE SHIMIZU Ball State University How can an architectural exhibition speak to ideas Lasch, Plan B Architecture & Urbanism, Oyler Wu Collaborative, of between-ness? How can a temporal event for- studio:indigenous, and IKD. ever transform the understanding of a place? In - Washington Street installations: Five international design gal- 2014, along with a small talented team, we started leries commissioned designers to add interventions that would working on a project with the goal to transform and connect emerging trends in design to the commercial core- Studio heighten awareness of the architectural legacy of Formafantasma, Pettersen & Hein, Productora, Cody Hoyt, and Columbus, Indiana, through the production of con- Snarkitecture temporary architecture and design. In this paper, we - University Installations: Six Midwest universities built prototypes will describe Exhibit Columbus’ curatorial premises beside Central Middle School and North Christian church- Ball State of dialogue and context through the lens of our mul- University, College of Architecture and Planning; The Ohio State tiple roles: as members of the steering committee University, Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture; University of that defined its curatorial vision, as university instal- Cincinnati, School of Architecture and Interior Design; University of lation coordinators who hope to impact architecture Kentucky, College of Design, School of Architecture; University of Michigan, Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, education in the Midwest, faculty research, and thoughts on pedagogy, and finally as instructor for - High School Installations: Local students did a design-build at the a design-build studio. historic post office. -

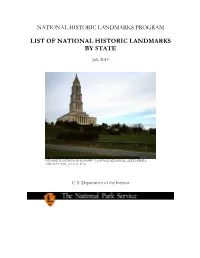

National Historic Landmarks Program

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM LIST OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE July 2015 GEORGE WASHINGTOM MASONIC NATIONAL MEMORIAL, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA (NHL, JULY 21, 2015) U. S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LISTING OF NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS BY STATE ALABAMA (38) ALABAMA (USS) (Battleship) ......................................................................................................................... 01/14/86 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, ALABAMA APALACHICOLA FORT SITE ........................................................................................................................ 07/19/64 RUSSELL COUNTY, ALABAMA BARTON HALL ............................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 COLBERT COUNTY, ALABAMA BETHEL BAPTIST CHURCH, PARSONAGE, AND GUARD HOUSE .......................................................... 04/05/05 BIRMINGHAM, JEFFERSON COUNTY, ALABAMA BOTTLE CREEK SITE UPDATED DOCUMENTATION 04/05/05 ...................................................................... 04/19/94 BALDWIN COUNTY, ALABAMA BROWN CHAPEL A.M.E. CHURCH .............................................................................................................. 12/09/97 SELMA, DALLAS COUNTY, ALABAMA CITY HALL ...................................................................................................................................................... 11/07/73 MOBILE, MOBILE COUNTY, -

Collection on Exhibit Columbus

DIDACTIC COLLECTION ON EXHIBIT COLUMBUS A Selection for the inaugural 2016 Exhibit Columbus Symposium, "Foundations and Futures" DIDACTIC III Collection on Exhibit Columbus A selection for the inaugural 2016 Exhibit Columbus Symposium, "Foundations and Futures" At Exhibit Columbus we are thrilled to partner with PRINTtEXT to produce this is- sue of Didactic. I hope that you’ll read through these pages with thoughtful attention, as each word was written and each page designed with the same kind of intentionali- ty that has made Columbus, Indiana an internationally recognized city for its pursuit of good design. Enrique has written perceptive histories of the nine sites we’ve select- ed to host new temporary installations next year. These installations, built to respond artistically and architecturally to each site’s unique design history, will be featured in the 2017 Exhibit Columbus exhibition. Amy and Matt’s articles show what Colum- bus has meant to them from a personal perspective. All of this work snaps into clari- ty with the beautiful images of Hadley Fruits. I hope you enjoy this issue—and make plans to attend the inaugural symposium, “Foundations and Futures,” Sept 29 - Oct 1. —Richard McCoy, Director, Landmark Columbus Creative Directors / Editors: Janneane & Benjamin Blevins Published by: PRINTtEXT Photography: Hadley Fruits Features Editor: Eleanor Rust Contributors: Enrique Ramirez “A Home in The Modern World: Sites & Histories of Columbus, Indiana” 2 Site One: First Christian Church (1942) 3 Site Two: Irwin Conference Center -

Association of Architecture Organizations 2013 Members Weekend Columbus, in (July 18-20)

Association of Architecture Organizations 2013 Members Weekend Columbus, IN (July 18-20) Participants Allison Arieff, San Francisco Planning + Urban Research Association Gwen Berlekamp, The Center for Architecture and Design (Columbus, OH) Greg Brown, Dallas Center for Architecture John Claypool, Philadelphia Center for Architecture John Comazzi, University of Minnesota College of Design (Assistant Professor, School of Architecture) Nate Eudaly (and wife, Jean, and son, Daniel), Dallas Architecture Forum Patricia Feller, Chicago Architecture Foundation Docent Stephen Glassman, Design Center Pittsburgh Ruth Gless, Board Member, The Center for Architecture and Design (Columbus, OH) James Gysler, Chicago Architecture Foundation Member Kathleen Gysler, Chicago Architecture Foundation Member Becky Harper, Columbus Area Visitors Center Erin Hawkins, Columbus Area Visitors Center Henry Kuehn, Columbus Area Visitors Center Docent; Chicago Architecture Foundation Docent and Life Trustee Lynn Lucas, Columbus Area Visitors Center Julie Lilie, Chicago Architecture Foundation Member Kelly Lyons, Cranbrook Art Museum Klaus Mayer, Alaska Design Forum Susan McDaid, The American Institute of Architects (National HQ) Srini Murthy, Hyderabad Architecture Foundation (India) Don Nissen, Columbus Area Visitors Center Jason Nu, University of Wisconsin-Madison (Doctoral Candidate, Department of Geography) Margie O’Driscoll, Center for Architecture + Design, San Francisco Joyce Orwin, Columbus Area Visitors Center Lynn Osmond, Chicago Architecture Foundation