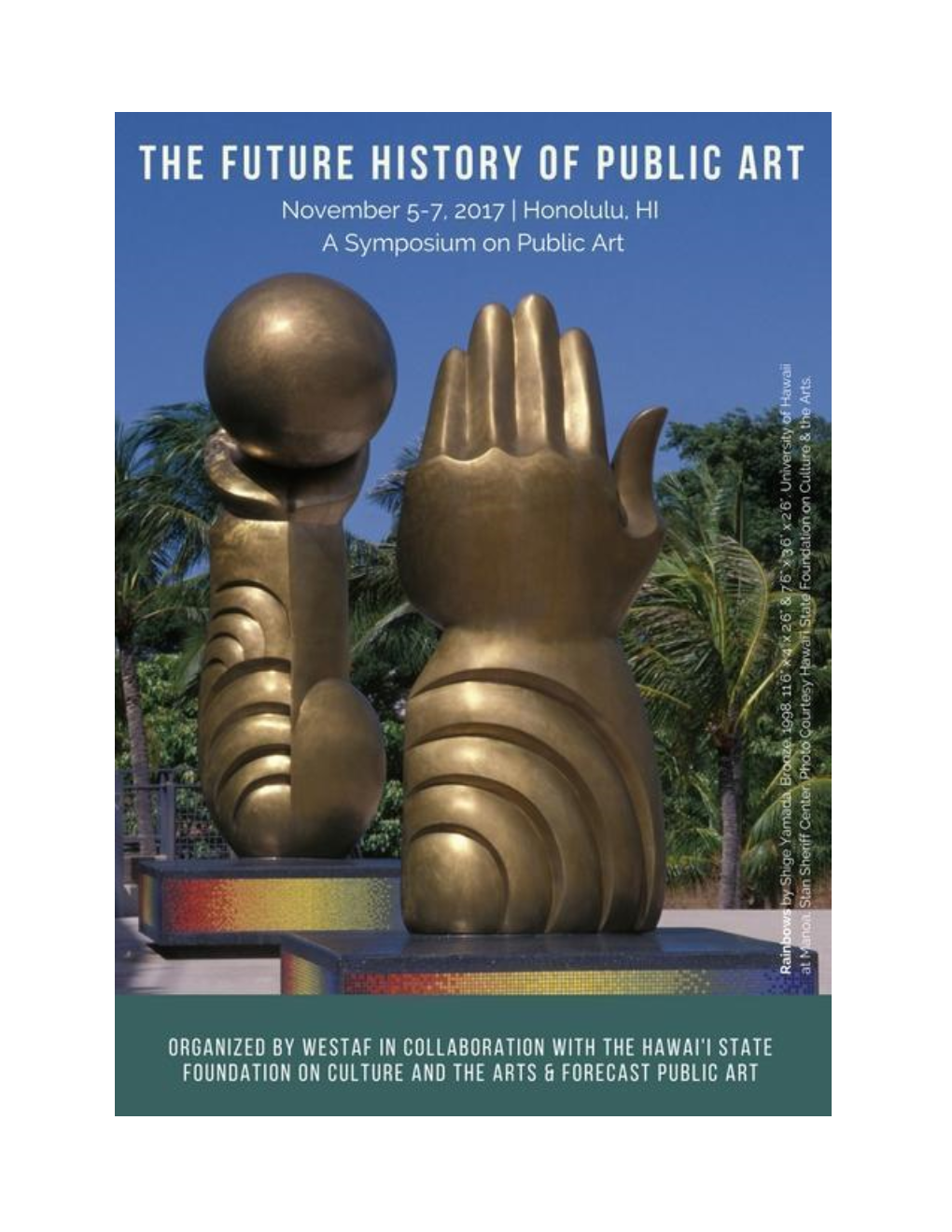

The Future History of Public Art Symposium Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Mile Downtown Architecture Loop

EXIT 76 TOWN OF HOPE ANTIQUE MALL IUPUC COLUMBUS EDINBURGH MUNICIPAL AIRPORT PREMIUM OUTLETS ATTERBURY BAKALAR AIR MUSEUM 65 TAYLORSVILLE IVY TECH STATE RD. 9 RD. STATE SOCCER FIELDS CHAPMAN T. BLACKWELL III PARK FREEDOM FIELD PLAYGROUND 31 PAR 3 GOLF FLATROCK RIVER COURSE . - 31 31 9 NORTH H.S. FAIROAKS MALL APP. 3.5 MILES 46 LINCOLN PARK 9 46 DONNER PARK HOSPITAL NOBLITT PARK NOBLITT PARK 31 COUNTY RD. 650E RD. COUNTY CLIFTY CREEK ZAHARAKOS ICE CREAM PARLOR AND MUSEUM OTTER CREEK KIDSCOMMONS GOLF COURSE CHILDREN’S MUSEUM N F 3-MILE DOWNTOWN GREENBELT ARCHITECTURE LOOP GOLF COURSE FLATROCK RIVER MILL RACE COUNTY RD. 50N COVERED BRIDGE WASHINGTON FRANKLIN LAFAYETTE PEARL B LINDSEY BROWN JACKSON 8TH SUBJECT TO FLOODING MILL RACE CUMMINS H.Q. LIBRARY CENTRAL MIDDLE 31 PARK 7TH SAITOWITZ IRWIN CONF. CTR. PLANT ONE VISITORS EAST FORK, WHITE RIVER B CENTER DRIFTWOOD RIVER 5TH THREE-MILE RIDE LOOKOUT K;3 TOWER B CUMMINS INC. PLANT ONE 4TH 65 ELIEL SAARINEN 3RD < HIGH-TRAFFIC > < HIGH-TRAFFIC > SKOPOS 46 COUNTY RD. 100S HWY 4466 ST. PETER’S APP. 1.5 M. 2ND 46 B > BIKESHARE STATION 11 THE REPUBLIC CITY HALL EAST 4H FAIRGROUNDS HIGH CLIFTY CREEK 46 SCHOOL PARK HAW CREEK CERALAND EAST FORK WHITE RIVER 46 OGILVILLE LOUISVILLE REVISED MARCH 2010 SITES ALONG THE 3-MILE ARCHITECTURE LOOP (STARTING FROM THE VISITORS CENTER) CLEO ROGERS LIBRARY firms in the world and was named AIA Firm of the is a stop on The Indiana Covered Bridge Loop. The Architect : I.M. Pei, Pritzker Prize recipient | Pei also Year in both 1961 and again in 1996 - no other firm bridge is also, of course, a beautiful backdrop for designed Grand Louvre in Paris, and The Rock and has been awarded the prize more than once. -

Columbus/Columbus

The Avery Review Sarah M. Hirschman – Columbus/Columbus Columbus, the debut feature film from artist Kogonada set in the unlikely Citation: Sarah M. Hirschman, “Columbus/ Columbus,” in the Avery Review 28 (December midcentury architecture mecca of Columbus, Indiana, was released to great 2017), http://averyreview.com/issues/28/columbus- acclaim this August and enjoyed a slow but celebrated rollout in independent columbus. theaters throughout the fall. [1] The pseudonymous filmmaker has been hailed for the originality of his voice and technique, in particular for the careful framing [1] Columbus is home to an exceptional quantity of midcentury buildings designed by architecture of architecture in his film. His use of deep, flat focus and wide shots foreground heavyweights. This is entirely thanks to a philanthropic the settings and distances viewers from the action of the actors. In this film, effort that began in 1957 by Cummins Corporation Chairman and hometown booster J. Irwin Miller that architecture has the presence normally afforded a central character. I saw provided funding for services on public buildings if the architects working on them were selected from Columbus in Columbus, Indiana, surrounded by a pumped-up hometown crowd a pre-approved short list. While Columbus has been eager to call themselves out as extras or to identify their cars as captured in well known within architecture circles (in 2012 it was the AIA’s “sixth most architecturally important city in parking lots. There was a conspiratorial air in the Yes Cinema, a nonprofit the country”), its location about fifty miles south of Indianapolis and its relatively rural setting have kept it art-house theater where Columbus was enjoying the theater’s highest-grossing under-visited and off the national radar. -

Preserving Historic Places

PRESERVING HISTORIC PLACES INDIANA’S STATEWIDE PRESERVATION CONFERENCE APRIL 17-20, 2018 COLUMBUS, INDIANA 2 #INPHP2018 WBreedingabash streetscape: Farm: Courtesy, courtesy Bartholomew Wabash County County Historical Historical Museum Society GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to Preserving Historic Places: Indiana’s Statewide Preservation Conference, 2018. We are excited to bring the annual conference for the first time to Columbus, which earned the moniker “Athens of the Prairie” in the 1960s for its world-class design and enlightened leadership. You’ll have a chance to see the city’s architecture—including nineteenth-century standouts and the Mid-Century Modern landmarks that have earned the city international renown. In educational sessions, workshops, and tours, you’ll discover the economic power of preservation, learn historic building maintenance tips, and much more, while meeting and swapping successes and lessons with others interested in preservation and community revitalization. LOCATION OF EVENTS CONTINUING EDUCATION You’ll find the registration desk and bookstore at First CREDITS Christian Church, 531 5th Street. Educational sessions take place at the church and Bartholomew County Public Library The conference offers continuing education credits (CEU) at 536 5th Street. Free parking is available in the church’s and Library Education Units (LEU) for certain sessions and lots on Lafayette Street and in the lot north of the Columbus workshops, with certification by the following organizations: Visitors Center in the 500 block of Franklin Street. Parking AIA Indiana is also available in the garage in the 400 block of Jackson American Planning Association Street. Street parking is free but limited to three hours. American Society of Landscape Architects, Indiana Chapter Indiana State Library BOOKSTORE Indiana Professional Licensing Agency for Realtors The Conference Bookstore, managed by the Indiana Historical Check the flyer in your registration bag for information on all Bureau, carries books on topics covered in educational sessions. -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

LO 2019Cr Mill Race Marathon

MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS RUN&FUN // MILL RACE MARATHON 1 Proud sponsor: Our commitment to Columbus and Bartholomew County is strong. Offering 5 locations to serve you with full-service banking, insurance, investments, and 240 Jackson Street • 529 Washington Street 803 Washington Street • 1901 25th Street wealth advisory solutions, all 2310 W. Jonathan Moore Pike backed by a local team of (812)372-2265 • germanamerican.com financial professionals committed to customer service excellence. TR-35017766 MILL RACE MARATHON RUN&FUN OFFICIAL GUIDE to THE SEPTEMBER 27-28, 2019 2019 MILL Race Marathon PUBLISHER Bud Hunt EDITOR MILL RACE MARATHON SEPT. 27-28, 2019 Julie McClure 2019RUN FUNSEPTEMBER 21-22 assistant YOUR OFFICIAL GUIDE &TO THE BIG PARTY IN COLUMBUS managing editor Kirk Johannesen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Anna Perlich ON THE COVER Participants are shown at the start of the 2018 Mill Race Marathon. Race organizers have planned one huge party in downtown Columbus, and you don't have to be a runner to participate. You'll find a health and fitness expo, live music, activities for kids, food and more. Use this as your guide to everything you need to know about the races and events. Then go run and have some fun! ©2019 by AIM Media Indiana. All rights reserved. Reproduction of stories, photographs and advertisements without permission is prohibited. INFO: 812-379-5633 TABLE OF CONTENTS Getting started Entertainment Welcome 4 Finish on Fourth map 24 Schedule -

主題演講(一)Keynote Plenary (1)

主題演講(一)Keynote Plenary (1) ENESS《搖搖光》 The Light Seesaw by ENESS ENESS 創辦人兼創作總監寧錄 ‧ 韋斯及他的 Nimrod WEIS, Founder and Creative Director of ENESS and his team are 團隊,一直積極打造激發正能量的作品,期望 at the forefront of actively creating artworks that also stimulate powerful, 為人們帶來快樂和幸福感。特別在當前動盪的 positive emotions like joy, delight, happiness and well-being — needed all 環境中,這些藝術品顯得尤其重要。 the more during these times of worldwide upheaval. ENESS 的互動作品遍布全球商務空間、公共 Weis will speak about the importance of public engagement in ENESS’s 領域、藝術及文化機構、保健及遊樂場所。 interactive artworks, commissioned internationally for commercial spaces, 藉著分享一系列得獎作品——如《搖搖光》、 public realm, art and cultural institutions, healthcare and playgrounds. 《Jem》、《Sky Castle》和《Airship Or- Let us learn more about the process and challenges behind the creation chestra》和《LUMES》等,韋斯探討如何透 of award-winning artworks such as The Light Seesaw, Jem, Sky Castle, 過激發人們對於城市建築及公共藝術的大膽想 Airship Orchestra and LUMES; projects that are radically redefining the 像,刺激跨世代之間既深且廣的連繫,從而重 spaces and places in which they exist by stimulating deep, intergenerational 新定義我們所身處的空間。 connections and altering the ways that people expect to interact with built form and public art in their cities. 講者 Speaker 寧錄 ‧ 韋斯 | 澳洲 Nimrod WEIS | Australia ENESS 創辦人兼創作總監 Founder & Creative Director of ENESS 韋斯為雕塑家、科技創夢者、藝術家、設計 Part sculptor, part technologist dreamer, artist and designer, 師、ENESS(設計工作室)創辦人之一兼 Weis is one of the co-founders and Creative Director of 創作總監;專注於多媒體創作及設計,探討 ENESS, a multidisciplinary design studio dedicated to 虛擬與現實世界千絲萬縷的關係,致力打造 exploring the intersection between the virtual and the 出獨一無二的公共藝術/互動裝置品牌。 physical world via its unique brand of interactive public art 韋斯對未來的城市充滿熱情及好奇,相信透 installations worldwide. 過創作融合藝術與科技的作品,能夠將人與 Weis is passionate about a future of cities filled with new 人連繫起來;並期望藉著人與作品的互動, experiences designed to bind us as art and technology bring 帶動各種情緒體驗。作品的風格玩味性強, us closer together. -

LCF-Annualreport.Pdf

UTK Tower: Marshall Prado, 2018–19 UDRF Fellow Executive Summary The Columbus, Indiana community continues to demonstrate that the best way to have an authentically great place to live is through the process of working together with shared values and clear goals. Engaging excellent designers and relying upon a thoughtful process to build new buildings, landscapes, artworks, or reuse existing ones is a key part of our history. After more than seventy-five years, this tradition has created what we hold dear today: an internationally-recognized collection of architecture, art, and design that has become a defining characteristic of the community and the core of this city’s identity. Heritage Fund — The Community Foundation of Bartholomew County launched Landmark Columbus Foundation (LCF) in 2015 as one of its key programs to ensure that Columbus’ traditions and investments in design excellence are well cared for and can remain a source of inspiration for future generations. With the support of many in this community and those around the state and country, Heritage Fund’s program quickly became a community asset making a big difference through Exhibit Columbus and many progressive preservation efforts. 1 Executive Summary Bartholomew County Courthouse: Isaac Hodgson, 1874 In late 2019 Heritage Fund supported the move of this program to become a stand alone 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, with the mission to care for, celebrate, and advance the cultural heritage of Columbus, Indiana. At the start of 2020, the inaugural Board of Directors of LCF met to move the mission forward, and with dedicated staff, volunteers, and collaborators, this organization has made great progress and is poised for continued success far beyond today. -

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolatio

Agency Landscape + Planning Bryony Roberts Studio Frida Escobedo Studio MASS Design Group SO–IL Borderless Studio Extrapolation Factory LA-Más People for Urban Progress PienZa Sostenible Christopher Battaglia BSU Daniel Luis Martinez and Etien Santiago IU Viola Ago OSU and Hans Tursack MIT Sean Lally UIC and Matthew Wizinsky UC Sean Ahlquist UM Marshall Prado UTK Bartholomew Consolidated School Corporation Thirst 2019 2019 Exhibition J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize Good Design and the Community Presented by Cummins Inc. Exhibit Columbus is inspired by the 1986 exhibition, The J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize is the centerpiece Good Design and the Community: Columbus, Indiana, of Exhibit Columbus’ exhibition and symposium and created by the National Building Museum in Washington honors two great patrons of the Columbus community. when Columbus business leader and philanthropist The Miller Prize Recipients are international leaders that J. Irwin Miller became the first person inducted into were selected for their commitment to the transformative their Hall of Fame. power that architecture, art, and design has to improve people’s lives and make cities better places to live. With That exhibition honored the Miller family’s legacy of servant leadership and the entire city’s commitment to make Columbus the best community of its size. When profiled by this award, we bring these studios’ unique perspectives the Washington Post that year, Mr. Miller chose to emphasize the community’s process and involvement in building, rather than the architecture itself, as a source of his to Columbus to explore the traditions and values that hometown pride: “Architecture is something you can see. -

Houston Arts Alliance 2018 Artist Roster

2018 Artist Roster Fariba Abedin Houston, TX I have always been fascinated by the beauty of nature and its integral parts, colors, and geometry. The geometric shapes and the rich colors of Persian tile works appeal to me. The architecture and structures of the most unique domes in the mosques and their unparalleled mirror works still mesmerize me, reminding me of my childhood. My work emphasizes exploration of color using geometric abstraction as my foundation. www.faribaabedin.com Our work is usually characterized by a strong profile, a sense of humor, and Actual Size Artworks excellent craftsmanship. We are especially dedicated to works that change as a Stoughton, WI viewer walks past, creating a sense of discovery and keeping up interest upon www.actualsizeartworks.com repeated viewing. Adela Andea Houston, TX Formally, my work has a very distinctive style and it presents original and cutting edge ideas. I create light installations and light sculptures using the latest technologies in the industry and a variety of materials that suit my vision for each installation. I believe that the vibrant energy and the unique aesthetics of my work will bring liveliness, color, and brightness to any site in the Houston area. www.adelaandea.com Bennie Flores Ansell Houston, TX I realize the ethereal nature of my work does not lend itself to favorable long-lasting public art installations. However, I have been printing images of the light projections on dye infused metal which can be printed very large and are very moveable as well as permanent. Most recently, I started working with a laser cutter and a 3-D printer that will allow for new and sturdy presentations of my work and ideas. -

When Was Columbus Modern? the Word “Modern,” According to Webster's Means “Of, Related To, Or Characteristic of the Pres

When was Columbus Modern? The word “modern,” according to Webster’s means “of, related to, or characteristic of the present or immediate past.” And yet the modern architecture and design for which Columbus, Indiana is justly famous, was inaugurated by Eliel Saarinen at the First Christian Church in 1942! (Visitors will know the building from its gridded façade and 166 foot, geometric tower.) Other modern buildings in Columbus include the glass-framed Irwin Union Bank (now Irwin Conference Center) by Eero Saarinen (64 years old), and the red brick and concrete Cleo Roger Memorial Library by I.M. Pei (49 years old). The designer Paul Rand’s iconic, dancing C’s logo for the Columbus Visitor’s Center from 1974 just turned 44! Are these buildings and designs still modern, or should they be called old, or middle-aged? Modern architecture began in Europe during the first decades of the 20th Century. It was called modern because it served new needs, was up-to-date in engineering, and didn’t resemble anything that came before. This was intended to be a style- less architecture that responded only to purpose or need. Some of the key names associated with it are the Swiss Le Corbusier and the Germans Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. The latter’s famous catchphrase “less is more” (actually first used by Mies’ teacher, Peter Behrens) summarizes the belief of the modernists that the best architect is the one who designs least, and who permits function to dictate form. In the United States, modern architecture and design wasn’t fully embraced until after the second world war, when a new, national confidence permitted a broad jettisoning of historical forms and traditions. -

P.E. Macallister Collection

Collection # P 0492 P. E. MACALLISTER COLLECTION 1974–2010 (DVDS, 1982–2007) Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Series Contents Processed by Sarah Newell and Barbara Quigley June 12, 2012 Revised June 16, 2015 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 309 titles on DVD (1982–2007); 10 folders of manuscript and COLLECTION: printed materials (1974–2010) COLLECTION 1974–2010 (DVDs, 1982–2007) DATES: PROVENANCE: Donated by P.E. MacAllister, 2008; second accession in December 2008 of 94 DVDs of On Site programs (ca. 1983- 2006) from IUPUI special collections, who in turn got them from P.E. MacAllister; MacAllister Machinery newsletters mailed to IHS in 2010 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2008.0004, 2008.0380, 2010.0382X NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH P.E. (Pershing Edwin) MacAllister is chairman of the board at MacAllister Machinery Co., a Caterpillar dealership started by his father. He was born 30 August 1918 in Green Bay, Wisconsin, to Edwin W. and Hilda MacAllister. His father, a WWI veteran, named him Pershing after General John Joseph “Black Jack” Pershing. P.E. graduated from Carroll College in Waukesha, Wisconsin, with a major in history and minors in English and speech. Upon his graduation he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and reported for duty at the Muskogee, Oklahoma, Air Corps Primary Training School. -

Columbusvisitors Guide | Summer 2020

DISCOVER columbusVISITORS GUIDE | summer 2020 INSIDE: The Indiana Covered Bridge Loop AccommodAtions • shopping • dining • events • recreAtion Summer 2020 | DISCOVER COLUMBUS 1 THANKS FOR LETTING US BE YOUR TRUSTED ADVISOR FOR THE PAST 45 YEARS! ADVERSITY REVEALS TRUE CHARACTER ■ Thanks to our clients, Kirr, Marbach celebrated its 45th Anniversary on May 1, 2020. ■ We were established in 1975 under a single goal: to be a friendly, knowledgeable, trustworthy and reassuring source of financial guidance to our clients. Our founding values remain: ◆ Loyalty. We act as fiduciaries to our clients. Our interests are aligned with yours. ◆ Humility. We don’t know what’s going to happen next, but we’ve navigated through numerous bull and bear markets, economic booms and busts, market bubbles and crashes and seen investment fads come and go. ◆ Discipline. We focus on the long-term voyage. ◆ Responsibility. We do what we say we’re going to do. ■ Visit our new website at www.kirrmar.com to view ◆ Our Insights page, which contains timely content on investments and personal finance we have both curated and created. ◆ A video featuring David Kirr, CFA discussing how he and Terry Marbach, CFA founded the firm after working for J. Irwin Miller at Irwin Management Company. ■ Whether you have $1,000 or $10 million to invest, we’d love to invest alongside you. Please contact us at (812) 376-9444 or by email so we can learn what matters to you. Zach Greiner Matt Kirr Maggie Kamman, CMA Assoc. Director of Client Service Director of Client Service Assoc. Director of Client Service [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] TR-35045915 Registration of an investment advisor does not imply any level of skill or training.