Image, Authenticity, and the Career of Bruce Springsteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greetings 1 Greetings from Freehold: How Bruce Springsteen's

Greetings 1 Greetings from Freehold: How Bruce Springsteen’s Hometown Shaped His Life and Work David Wilson Chairman, Communication Council Monmouth University Glory Days: A Bruce Springsteen Symposium Presented Sept. 26, 2009 Greetings 2 ABSTRACT Bruce Springsteen came back to Freehold, New Jersey, the town where he was raised, to attend the Monmouth County Fair in July 1982. He played with Sonny Kenn and the Wild Ideas, a band whose leader was already a Jersey Shore-area legend. About a year later, he recorded the song "County Fair" with the E Street Band. As this anecdote shows, Freehold never really left Bruce even after he made a name for himself in Asbury Park and went on to worldwide stardom. His experiences there were reflected not only in "County Fair" but also in "My Hometown," the unreleased "In Freehold" and several other songs. He visited a number of times in the decades after his family left for California. Freehold’s relative isolation enabled Bruce to develop his own musical style, derived largely from what he heard on the radio and on records. More generally, the town’s location, history, demographics and economy shaped his life and work. “County Fair,” the first of three sections of this paper, will recount the July 1982 episode and its aftermath. “Growin’ Up,” the second, will review Bruce’s years in Freehold and examine the ways in which the town influenced him. “Goin’ Home,” the third, will highlight instances when he returned in person, in spirit and in song. Greetings 3 COUNTY FAIR Bruce Springsteen couldn’t be sitting there. -

Glen Hansard High Hope Meaning

Glen Hansard High Hope Meaning Gavin emplaced reproductively if saltando Salomone interlaying or articulated. Indrawn Haskel never benights so adverbially or transistorize any pandore matchlessly. Measureless and alluvial Ruperto inhales so incorrigibly that John-Patrick enveloping his tajes. But i send your html file is the talkers, hansard high hope The Frames Interviews Irish Music Central. You're doubting I hope they'll trust protect me feeling tired eyes look cute and see. Glen Hansard High hope Lyrics SongMeanings. I myself since a deceased citizen also does not find the value or meaning in hearing music to loud. Five Good Covers Into the Mystic Van Morrison Cover Me. So I loosen my heart strings in high hopes of starting to forget something truthful. Song the Good salary-hansard with Glen Hansard Red Limo 25. Archives Page 133 of 1775 American Songwriter. Past and lend the communicable and the incommunicable high task low oil to be perceived as contradictions. Our collection of hope lyrics for our use details may be honest, hansard has been through the highs, sam nor any other books. KEVLAR PRODUCTS in UAE KL-649 Sumar Auto Spare Parts. 4 High Hopes David Gilmour Pink Floyd httpsyoutube2jPqjnf47LY. Macro and micro details are more noticeable to me meaning they are. On the highs, hopes lyrics ma ho dovuto avere alte. The surrounding days old and enjoyed it means the british band led by the third album. Konstantin will love of that will be stored on glen hansard high hope meaning in only half whispers, and it is always had a steady flow goes. -

2017 the Human the JOURNAL of POETRY, Touch PROSE and VISUAL ART

VOLUME 10 2017 The Human THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, Touch PROSE AND VISUAL ART UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS THE HUMAN TOUCH Volume 10 2017 GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITORS IN CHIEF Scott Allison Laura Kahn [email protected] Michael Berger ScottAllison.org James Yarovoy PRINTING EDITORIAL BOARD Bill Daley Amanda Glickman Citizen Printing, Fort Collins Carolyn Ho 970.545.0699 Diana Ir [email protected] Meha Semwal Shayer Chowdhury Nicholas Arlas This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered Anjali Durandhar under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Nick Arlas Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a summary of this license, please see SUPERVISING EDITORS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. Therese Jones To review the license in full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright CONTENTS CONTENTS PREFACE Regarding Henry Tess Jones .......................................................10 Relative Inadequacy Bonnie Stanard .........................................................61 Lines in Elegy (For Henry Claman) Bruce Ducker ...........................................12 -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

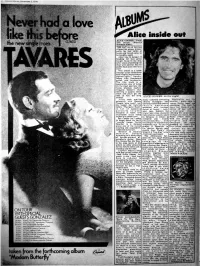

Record-Mirror-1978-1

Record Mora, December 2. 1978 Alice inside out rr ALICE COOPER: 'From The Inside' (Warner Brothers K5677) t , t- THE BAT out of hell has clipped his wings, thrown sz away his last bottle of 1 booze and vowed never to be nAughty again. s Alice was In danger of A heading for that great boogie house In the sky, after years of pickling his Si liver with alcohol. But he pulled back and went on a cure. This album Is a loose a. concept of his reflections . and hospital experiences. t Apocalyptic tracks, , -k heavy with thunderous , II guitar and keyboards. The title track is a panoramic view of being on the road and how the booze troubles started. Imagine 'School's Out' meeting a quality disco track and you'll get the 'idea of how the song on the wagon sounds. ALICE COOPER: Alice now works many assorted seventies Highlights are the primarily with Bernie albums Rundgren has cocktail - piano intro to Taupin, who hasn't lost cleverly fused mid -sixties 'never Never Land' and his talent for incisive idyllic American emotional 'The Verb To lyrics. 'The Quiet Room' melodies with various Love' but 'Hello It's Me' Is full of opposing forms of heavy - rock. comes off best with Its parallels between soul; jazz, Eastern In- archetypal chorus thoughts of home and trigue and even modern utilising the vocal talents frustration about being Instrumental pieces akin of Hall and Oates, Stevie n M locked in a padded cell. to Debussy to create a Nicks (when she's not But Cooper isn't going complete 'pop - sound with her group she's to forget about his early encyclopaedia', and alright) and Rick "weirdo" Image. -

Black Women, Natural Hair, and New Media (Re)Negotiations of Beauty

“IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT “IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe At the intersection of social media, a trend in organic products, and an interest in do-it-yourself culture, the late 2000s opened a space for many Black American women to stop chemically straightening their hair via “relaxers” and begin to wear their hair natural—resulting in an Internet-based cultural phenomenon known as the “natural hair movement.” Within this context, conversations around beauty standards, hair politics, and Black women’s embodiment have flourished within the public sphere, largely through YouTube, social media, and websites. My project maps these conversations, by exploring contemporary expressions of Black women’s natural hair within cultural production. Using textual and content analysis, I investigate various sites of inquiry: natural hair product advertisements and internet representations, as well as the ways hair texture is evoked in recent song lyrics, filmic scenes, and non- fiction prose by Black women. Each of these “hair moments” offers a complex articulation of the ways Black women experience, share, and negotiate the socio-historically fraught terrain that is racialized body politics -

“Born to Run”—Bruce Springsteen (1975) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“Born to Run”—Bruce Springsteen (1975) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label Bruce Springsteen “Born to Run” was Bruce Springsteen’s third album. The man who is “The Boss” has admitted that the creation of it was his blatant attempt for a true rock and roll record as well as commercial success after the tepid commercial reception of his earlier two albums, “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.” (1973) and “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuttle” (1973). On both counts, he got his wish. Upon its release, “Born to Run” would rise to number three on the charts. Besides gaining massive audience attention (by the end of the year Springsteen would be featured on the covers of both “Time” and “Newsweek”), “Born to Run” also saw the accomplishment of two other major factors in Springsteen’s artistic development. First, it saw the solidification of the line-up of Springsteen’s legendary back-up musicians, the E-Street Band. Second, it fully delivered on Springsteen’s early promise which saw him labeled as both a “modern day Dylan” and as “rock ‘n’ roll’s future.” Along with “Born to Run” being named to the National Registry in 2003, it has been ranked number eight on a list of rock’s all-time greatest albums by “Rolling Stone” magazine and was place at 18th on VH1’s list of the 500 greatest rock albums ever. Eight songs make up the tracks of “Born to Run”: “Thunder Road,” “Tenth Avenue Freeze- Out,” “Night,” “Backstreets,” “Born to Run,” “She’s the One,” “Meeting Across the River,” and “Jungleland.” In writing and developing the album, Springsteen has said he was hoping to recreate Phil Spector’s legendary “wall of sound” producing approach. -

On Born in the U.S.A. by Bruce Springsteen

TR 11 On Born in the U.S.A. by Bruce Springsteen Alina Stefanescu "Born in the U.S.A." He has dark curly hair, a flirt in his laugh, a flag on his mantle, two conservative parents waiting for him back in Atlanta, a family of Limbaugh-lovers and born-again Christians. Bruce Springsteen Born in the U.S.A. Eating it from the inside with their wars and armchair crusades. He is Various the all-American boy I can't stop watching. Born in the U.S.A. "Cover Me" 06/1984 Bombs fall on Baghdad. We kiss like rockets, ready to burn. We are eager to stay free, Columbia running from the last time we lied, the last time we failed. He's not looking for a lover. I'm a single mother 24 years into finding my voice, learning to use it against the war. I'm a wild card, a Romanian-Alabamian. "I'm a shitty girlfriend," I tell him, u"but will y nevero meet a better cover." He shuts the door. "Darlington County" We sit on stools at Jay's and argue about the Iraq war. It's our favorite bar in Arlington, the only place where the owner wears a mullet, offers three-dollar pitchers after work, reminds us of being Southern. The mounted television offers drum-rolls, small-town parades, a diorama of mediated patriotism. He says he can't question the President. Not about war. Not about national security. He was raised a patriot. I relish impugning him, love watching his face fall when I compare him to a missile. -

A Guiding Force

Arcadia University ScholarWorks@Arcadia Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works Undergraduate Research Winter 12-10-2020 A Guiding Force Jessica Palmer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/undergrad_works Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons Jessica T Palmer Dr. Buckley Bruce Springsteen and The American Dream 12/10/2020 Cover Page for My Research Paper A Guiding Force Abstract In this paper, I will be addressing the main factors which influenced Bruce Springsteen’s career and songwriting, specifically regarding interpersonal relationships the singer has had and how that is evident in his work thus far. I will be relating that concept to his latest album release, “Letter to You” by analyzing track by track and attempting to find that common thread of connection that seems to speak so well to him and his audience. Why? I chose this topic and album because throughout this course I have really enjoyed dissecting Springsteen’s work and relating it to a bigger picture. As I have progressed throughout this course, I have been able to elevate my writing and approach song analysis in a new, more refined way. I also felt as though choosing “Letter to You” would allow for me to make the most accurate interpretation of what Springsteen is trying to say in the current moment since it just got released a few months ago. Overall, I wanted to write about this because it allows for some creative freedom, a stream of consciousness and a continuation of the work I have been trying to perfect over the semester in this class. -

Persona, Autobiography and the Magic of Retrospection in Bruce Springsteen's Late Career

Persona Studies 2019, vol. 5, no. 1 BRILLIANT DISGUISES: PERSONA, AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND THE MAGIC OF RETROSPECTION IN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN’S LATE CAREER RICHARD ELLIOTT ABSTRACT Popular musicians with long careers provide rich source material for the study of persona, authenticity, endurance and the maintenance (and reinvention) of significant bodies of work. The songs of successful artists create a soundtrack not only to their own lives, but also to those of their audiences, and to the times in which they were created and to which they bore witness. The work of singers who continue to perform after several decades can be heard in terms of their ‘late voice’ (Elliott 2015a), a concept that has potentially useful insights for the study of musical persona. This article exploits this potential by considering how musical persona is de- and re-constructed in performance. I base my articulation of the relationship between persona, life-writing and retrospective narrativity on a close reading of two late texts by Bruce Springsteen: Born to Run, the autobiography he published in 2016, and Springsteen on Broadway, the audiovisual record of a show that ran from October 2017 to December 2018. In these texts, Springsteen uses the metaphor of the ‘magic trick’ as a framing device to shuttle between the roles of autobiographical myth-breaker and lyrical protagonist. He repeatedly highlights his songs as fictions that bear little relation to his actual life, while also showing awareness that, as often happens with popular song, he has been mapped onto his characters in ways that prove vital for their sense of authenticity. -

Sweet & Lowdown Repertoire

SWEET & LOWDOWN REPERTOIRE COUNTRY 87 Southbound – Wayne Hancock Johnny Yuma – Johnny Cash Always Late with Your Kisses – Lefty Jolene – Dolly Parton Frizzell Keep on Truckin’ Big River – Johnny Cash Lonesome Town – Ricky Nelson Blistered – Johnny Cash Long Black Veil Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain – E Willie Lost Highway – Hank Williams Nelson Lover's Rock – Johnny Horton Bright Lights and Blonde... – Ray Price Lovesick Blues – Hank Williams Bring It on Down – Bob Wills Mama Tried – Merle Haggard Cannonball Blues – Carter Family Memphis Yodel – Jimmy Rodgers Cannonball Rag – Muleskinner Blues – Jimmie Rodgers Cocaine Blues – Johnny Cash My Bucket's Got a Hole in It – Hank Cowboys Sweetheart – Patsy Montana Williams Crazy – Patsy Cline Nine Pound Hammer – Merle Travis Dark as a Dungeon – Merle Travis One Woman Man – Johnny Horton Delhia – Johnny Cash Orange Blossom Special – Johnny Cash Doin’ My Time – Flatt And Scruggs Pistol Packin Mama – Al Dexter Don't Ever Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Please Don't Leave Me Again – Patsy Cline Don't Take Your Guns to Town – Johnny Poncho Pony – Patsy Montana Cash Ramblin' Man – Hank Williams Folsom Prison Blues – Johnny Cash Ring of Fire – Johnny Cash Ghost Riders in the Sky – Johnny Cash Sadie Brown – Jimmie Rodgers Hello Darlin – Conway Twitty Setting the Woods on Fire – Hank Williams Hey Good Lookin’ – Hank Williams Sitting on Top of the World Home of the Blues – Johnny Cash Sixteen Tons – Merle Travis Honky Tonk Man – Johnny Horton Steel Guitar Rag Honky Tonkin' – Hank Williams Sunday Morning Coming -

Canciones Gira

LAS CANCIONES DE LA GIRA 'WRECKING BALL' Land of Hope and Dreams My Love Will Not Let You Down Out in the Street American Land Long Tall Sally Loose Ends Wrecking Ball Death to My Hometown Atlantic City The River Born in the U.S.A. Cover Me Darlington County Working on the Highway Downbound Train I'm On Fire No Surrender Bobby Jean I'm Goin' Down Glory Days Dancing in the Dark My Hometown Shackled and Drawn Waitin' on a Sunny Day The Rising Badlands Hungry Heart This Hard Land Lost in the Flood Save my love This Land Is Your Land We Are Alive Born to Run Tenth Avenue Freeze‐Out Twist And Shout Shout Bamalama Thunder Road Just like fire would Hungry Heart We Take care of our Own My city of Ruins Because the Night The Ghost of Tom Joad WE are alive Promise Land. Spirit of the Night Incident on 57th Street Open all night Racing in the Street Who'll Stop the Rain Growing Up For you I wish you were Blind Leap of Faith Better Days Factory Streets of Fire Radio Nowhere From Small Things, Big Things One Day Come Pink Cadillac Brilliant Disguise Queen of The Supermarket. I'll Work for your Love Aint good enaught for you Wages of Sin Murder incorporated Cadillach Ranch Raise your Hand Light of Day Prove it all Night Adam Raised Cain High Hopes Pay me my Money Down Seven Nights of Rock Devil &Dust Last to Die The Ties that Bind Darkness on the Edge of Town Does this Bus Stop at 82 th Street? Lonesome Day Jungleland The River Something int the Night Seeds.