Separation of Powers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Constitution of Malaysia

LAWS OF MALAYSIA REPRINT FEDERAL CONSTITUTION Incorporating all amendments up to 1 January 2006 PUBLISHED BY THE COMMISSIONER OF LAW REVISION, MALAYSIA UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISION OF LAWS ACT 1968 IN COLLABORATION WITH PERCETAKAN NASIONAL MALAYSIA BHD 2006 Laws of Malaysia FEDERAL CONSTITUTION First introduced as the Constitution … 31 August 1957 of the Federation of Malaya on Merdeka Day Subsequently introduced as the … … 16 September 1963 Constitution of Malaysia on Malaysia Day PREVIOUS REPRINTS First Reprint … … … … … 1958 Second Reprint … … … … … 1962 Third Reprint … … … … … 1964 Fourth Reprint … … … … … 1968 Fifth Reprint … … … … … 1970 Sixth Reprint … … … … … 1977 Seventh Reprint … … … … … 1978 Eighth Reprint … … … … … 1982 Ninth Reprint … … … … … 1988 Tenth Reprint … … … … … 1992 Eleventh Reprint … … … … … 1994 Twelfth Reprint … … … … … 1997 Thirteenth Reprint … … … … … 2002 Fourteenth Reprint … … … … … 2003 Fifteenth Reprint … … … … … 2006 Federal Constitution CONTENTS PAGE ARRANGEMENT OF ARTICLES 3–15 CONSTITUTION 17–208 LIST OF AMENDMENTS 209–211 LIST OF ARTICLES AMENDED 212–229 4 Laws of Malaysia FEDERAL CONSTITUTION NOTE: The Notes in small print on unnumbered pages are not part of the authoritative text. They are intended to assist the reader by setting out the chronology of the major amendments to the Federal Constitution and for editorial reasons, are set out in the present format. Federal Constitution 3 LAWS OF MALAYSIA FEDERAL CONSTITUTION ARRANGEMENT OF ARTICLES PART I THE STATES, RELIGION AND LAW OF THE FEDERATION Article 1. Name, States and territories of the Federation 2. Admission of new territories into the Federation 3. Religion of the Federation 4. Supreme Law of the Federation PART II FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES 5. Liberty of the person 6. Slavery and forced labour prohibited 7. -

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

OPENING of the LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General

OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2021 Speech by Attorney-General, Mr Lucien Wong, S.C. 11 January 2021 May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Justices of the Court of Appeal, Judges of the Appellate Division, Judges and Judicial Commissioners, Introduction 1. The past year has been an extremely trying one for the country, and no less for my Chambers. It has been a real test of our fortitude, our commitment to defend and advance Singapore’s interests, and our ability to adapt to unforeseen difficulties brought about by the COVID-19 virus. I am very proud of the good work my Chambers has done over the past year, which I will share with you in the course of my speech. I also acknowledge that the past year has shown that we have some room to grow and improve. I will outline the measures we have undertaken as an institution to address issues which we faced and ensure that we meet the highest standards of excellence, fairness and integrity in the years to come. 2. My speech this morning is in three parts. First, I will talk about the critical legal support which we provided to the Government throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Second, I will discuss some initiatives we have embarked on to future-proof the organisation and to deal with the challenges which we faced this past year, including digitalisation and workforce changes. Finally, I will share my reflections about the role we play in the criminal justice system and what I consider to be our grave and solemn duty as prosecutors. -

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Solicitor General April 30, 2021

U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Solicitor General Washington, D.C. 20530 April 30, 2021 Honorable Scott S. Harris Clerk Supreme Court of the United States Washington, D.C. 20543 Re: Biden, et al. v. Sierra Club, et al., No. 20-138 Dear Mr. Harris: On February 3, 2021, this Court granted the government’s unopposed motion to hold the above-captioned case in abeyance and to remove the case from the February argument calendar. The purpose of this letter is to advise the Court of recent factual developments in the case— although we do not believe those developments warrant further action by the Court at this time. This case concerns actions taken by the then-Acting Secretary of Defense pursuant to 10 U.S.C. 284 to construct a wall at the southern border of the United States during the prior Administration, using funds transferred between Department of Defense (DoD) appropriations accounts under Sections 8005 and 9002 of the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2019 (2019 Act), Pub. L. No. 115-245, Div. A, Tit. VIII, 132 Stat. 2999. The questions presented are whether respondents have a valid cause of action to challenge those transfers and, if so, whether the transfers were lawful. Following the change in Administration, however, this Court granted the government’s motion to hold the case in abeyance in light of President Biden’s January 20, 2021, Proclamation directing the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of Homeland Security to “pause work on each construction project on the southern border wall, to the extent permitted by law, as soon as possible” and to “pause immediately the obligation of funds related to construction of the southern border wall, to the extent permitted by law.” Proclamation No. -

Head B Attorney-General's Chambers

19 HEAD B ATTORNEY-GENERAL'S CHAMBERS OVERVIEW Mission Statement Serving Singapore's interests and upholding the rule of law through sound advice, effective representation, fair and independent prosecution and accessible legislation. FY2021 EXPENDITURE ESTIMATES Expenditure Estimates by Object Class BLANK Actual Estimated Revised Estimated Code Object Class FY2019 FY2020 FY2020 FY2021 Change Over FY2020 BLANK TOTAL EXPENDITURE $179,125,101 $204,500,000 $182,800,000 $202,000,000 $19,200,000 10.5% Main Estimates $167,743,431 $198,836,000 $178,078,100 $193,777,000 $15,698,900 8.8% OPERATING EXPENDITURE1 $167,735,631 $198,736,000 $178,028,100 $193,727,000 $15,698,900 8.8% RUNNING COSTS $167,720,467 $198,719,500 $178,008,500 $193,707,300 $15,698,800 8.8% Expenditure on Manpower $128,799,723 $146,778,900 $135,897,200 $144,458,000 $8,560,800 6.3% 1400 Other Statutory Appointments 5,104,217 6,072,000 5,220,000 7,000,000 1,780,000 34.1 1500 Permanent Staff 123,649,014 140,651,900 130,639,200 137,400,000 6,760,800 5.2 1600 Temporary, Daily-Rated & Other Staff 46,492 55,000 38,000 58,000 20,000 52.6 Other Operating Expenditure $35,260,744 $48,280,600 $38,451,300 $45,589,300 $7,138,000 18.6% 2100 Consumption of Products & Services 28,301,295 36,284,600 31,706,700 35,882,700 4,176,000 13.2 2300 Manpower Development 4,330,903 6,871,100 3,467,200 4,953,700 1,486,500 42.9 2400 International & Public Relations, Public 918,016 1,540,900 125,700 1,579,900 1,454,200 n.a. -

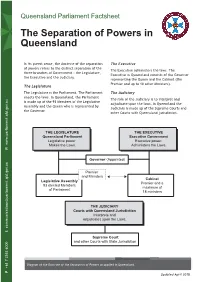

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

The Common Law Power of State Attorneys- General to Supersede Local Prosecutors*

1951] NOTES under the antitrust laws "based in whole or in part" on any matter com- plained of in the government proceeding. 17 Every plaintiff who comes within the terms of this provision should be forced to bring suit within a short period-two years, perhaps-after entry of a final judgment or decree in the government action.'8 The effect of such a modification on plaintiffs would vary: where the government suit began during the last two years of a plaintiff's statutory period, his time would be extended; in all other instances, it would be shortened. 19 Where the limitations period is lengthened, two years would provide ample time to bring an action. Where shortened, claim- ants whose actions would otherwise have been preserved for three, four, or five years after the end of the government suit, would be forced to litigate promptly. Plaintiffs thus restricted would have sufficient time to appraise their chances and to prepare their cases, given the advantage of prima facie evidence in the event of a government victory, and what is usually an ex- haustive record. Moreover, with such a record plaintiffs should be better 2 able to utilize the discovery provisions of the Federal Rules. But here, as in other instances, the exact period chosen is not the impor- tant thing. What is important is the pressing need for uniformity. Congress should move to meet it. THE COMMON LAW POWER OF STATE ATTORNEYS- GENERAL TO SUPERSEDE LOCAL PROSECUTORS* ENFORCEMENT of state penal law is traditionally the responsibility of local prosecutors.' But in recent years there has been a demand for more cen- tralized control of state prosecution policy.2 Centralization, it is urged, will 17. -

The Administration of Criminal Justice in Malaysia: the Role and Function of Prosecution

107TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE PARTICIPANTS’ PAPERS THE ADMINISTRATION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN MALAYSIA: THE ROLE AND FUNCTION OF PROSECUTION Abdul Razak Bin Haji Mohamad Hassan* INTRODUCTION PART I Malaysia as a political entity came into A. Constitutional History being on 16 September 1963, formed by The territories of Malaysia had been part federating the then independent of the British Empire for a long time. After Federation of Malaya with Singapore, the Second World War, there was a brief North Borneo (renamed Sabah) and period of British military administration. Sarawak, the new federation being A civilian government came into being in Malaysia and remaining and independent 1946 in the form of a federation known as country within the Commonwealth. On 9 the Malayan Union consisting of the eleven August 1965, Singapore separated to states of what is now known as West become a fully independent republic within Malaysia. This Federation of Malaya the Commonwealth. So today Malaysia is attained its independence on 31 August a federation of 13 states, namely Johore, 1957. In 1963, the East Malaysian states Kedah, Kelantan, Selangor, Negeri of Sabah and Sarawak joined the Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Federation and was renamed “Malaysia”. Trengganu, Malacca, Penang, Sabah and Sarawak, plus a compliment of two federal B. Parliamentary Democracy and territories namely, Kuala Lumpur and Constitutional Monarchy Labuan. The Federal constitution provides for a Insofar as its legal system is concerned, parliamentary democracy at both federal it was inherited from the British when the and state levels. The members of each state Royal Charter of Justice was introduced in legislature are wholly elected and each Penang on 25 March 1807 under the aegis state has a hereditary ruler (the Sultan) of the East India Company. -

Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies

1 Christoph Grabenwarter Separation of Powers and the Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent Bodies Keynote Speech 16 January 2011 2nd Congress of the World Conference on Constitutional Justice, Rio de Janeiro 1. Introduction Separation of Power is one of the basic structural principles of democratic societies. It was already discussed by ancient philosophers, deep analysis can be found in medieval political and philosophical scientific work, and we base our contemporary discussion on legal theory that has been developed in parallel to the emergence of democratic systems in Northern America and in Europe in the 18 th Century. Separation of Powers is not an end in itself, nor is it a simple tool for legal theorists or political scientists. It is a basic principle in every democratic society that serves other purposes such as freedom, legality of state acts – and independence of certain organs which exercise power delegated to them by a specific constitutional rule. When the organisers of this World Conference combine the concept of the separation of powers with the independence of constitutional courts, they address two different aspects. The first aspect has just been mentioned. The independence of constitutional courts is an objective of the separation of powers, independence is its result. This is the first aspect, and perhaps the aspect which first occurs to most of us. The second aspect deals with the reverse relationship: independence of constitutional courts as a precondition for the separation of powers. Independence enables constitutional courts to effectively control the respect for the separation of powers. As a keynote speech is not intended to provide a general report on the results of the national reports, I would like to take this opportunity to discuss certain questions raised in the national reports and to add some thoughts that are not covered by the questionnaire sent out a few months ago, but are still thoughts on the relationship between the constitutional principle and the independence of constitutional judges. -

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body

Separation of Powers Between County Executive and County Fiscal Body Karen Arland Ice Miller LLP September 27, 2017 Ice on Fire Separation of Powers Division of governmental authority into three branches – legislative, executive and judicial, each with specified duties on which neither of the other branches can encroach A constitutional doctrine of checks and balances designed to protect the people against tyranny 1 Ice on Fire Historical Background The phrase “separation of powers” is traditionally ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Also known as “Montesquieu’s tri-partite system,” the theory was the division of political power between the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary as the best method to promote liberty. 2 Ice on Fire Constitution of the United States Article I – Legislative Section 1 – All legislative Powers granted herein shall be vested in a Congress of the United States. Article II – Executive Section 1 – The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. Article III – Judicial The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. 3 Ice on Fire Indiana Constitution of 1816 Article II - The powers of the Government of Indiana shall be divided into three distinct departments, and each of them be confided to a separate body of Magistracy, to wit: those which are Legislative to one, those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judiciary to another: And no person or collection of persons, being of one of those departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted. -

Reform of the Office of Attorney General

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on the Constitution 7th Report of Session 2007–08 Reform of the Office of Attorney General Report with Evidence Ordered to be printed 2 April 2008 and published 18 April 2008 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords London : The Stationery Office Limited £price HL Paper 93 Select Committee on the Constitution The Constitution Committee is appointed by the House of Lords in each session with the following terms of reference: To examine the constitutional implications of all public bills coming before the House; and to keep under review the operation of the constitution. Current Membership Viscount Bledisloe Lord Goodlad (Chairman) Lord Lyell of Markyate Lord Morris of Aberavon Lord Norton of Louth Baroness O’Cathain Lord Peston Baroness Quin Lord Rodgers of Quarry Bank Lord Rowlands Lord Smith of Clifton Lord Woolf Declaration of Interests A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld/ldreg/reg01.htm Publications The reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee are available on the internet at: http://www.parliament.uk/hlconstitution Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at www.parliamentlive.tv General Information General Information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is on the internet at: http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/parliamentary_committees26.cfm Contact Details All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Select Committee on the Constitution, Committee Office, House of Lords, London, SW1A 0PW.