Do Rufous Common Cuckoo Females Indeed Mimic a Predator? an Experimental Test

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31St October to 16Th November 2016 (17 Days)

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31st October to 16th November 2016 (17 days) The Critically Endangered South Island Takahe by Erik Forsyth Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Erik Forsyth RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive II Trip Report 2016 2 Tour Summary New Zealand is a must for the serious seabird enthusiast. Not only will you see a variety of albatross, petrels and shearwaters, there are multiple- chances of getting out on the high seas and finding something unusual. Seabirds dominate this tour and views of most birds are alongside the boat. There are also several land birds which are unique to these islands: kiwis - terrestrial nocturnal inhabitants, the huge swamp hen-like Takahe - prehistoric in its looks and movements, and wattlebirds, the saddlebacks and Kokako - poor flyers with short wings Salvin’s Albatross by Erik Forsyth which bound along the branches and on the ground. On this tour we had so many highlights, including close encounters with North Island, South Island and Little Spotted Kiwi, Wandering, Northern and Southern Royal, Black-browed, Shy, Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses, Mottled and Black Petrels, Buller’s and Hutton’s Shearwater and South Island Takahe, North Island Kokako, the tiny Rifleman and the very cute New Zealand (South Island wren) Rockwren. With a few members of the group already at the hotel (the afternoon before the tour started), we jumped into our van and drove to the nearby Puketutu Island. Here we had a good introduction to New Zealand birding. Arriving at a bay, the canals were teeming with Black Swans, Australasian Shovelers, Mallard and several White-faced Herons. -

Frequency-Dependent Selection by Wild Birds Promotes Polymorphism in Model Salamanders

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Ecology and Evolutionary Biology July 2013 Frequency-dependent selection by wild birds promotes polymorphism in model salamanders Benjamin M. Fitzpatrick University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Kim Shook University of Tennessee - Knoxville Reuben Izally Farragut High School Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_ecolpubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation BMC Ecology 2009, 9:12 doi:10.1186/1472-6785-9-12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Ecology and Evolutionary Biology by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BMC Ecology BioMed Central Research article Open Access Frequency-dependent selection by wild birds promotes polymorphism in model salamanders Benjamin M Fitzpatrick*1, Kim Shook2,3 and Reuben Izally2,3 Address: 1Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville TN 37996, USA, 2Pre-collegiate Research Scholars Program, University of Tennessee, Knoxville TN 37996, USA and 3Farragut High School, Knoxville TN 37934, USA Email: Benjamin M Fitzpatrick* - [email protected]; Kim Shook - [email protected]; Reuben Izally - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 8 May 2009 Received: 10 February 2009 Accepted: 8 May 2009 BMC Ecology 2009, 9:12 doi:10.1186/1472-6785-9-12 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6785/9/12 © 2009 Fitzpatrick et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. -

The Evolution of Müllerian Mimicry

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Naturwissenschaften (2008) 95:681–695 DOI 10.1007/s00114-008-0403-y REVIEW The evolution of Müllerian mimicry Thomas N. Sherratt Received: 9 February 2008 /Revised: 26 April 2008 /Accepted: 29 April 2008 /Published online: 10 June 2008 # Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract It is now 130 years since Fritz Müller proposed systems based on profitability rather than unprofitability an evolutionary explanation for the close similarity of co- and the co-evolution of defence. existing unpalatable prey species, a phenomenon now known as Müllerian mimicry. Müller’s hypothesis was that Keywords Müllerian mimicry. Anti-apostatic selection . unpalatable species evolve a similar appearance to reduce Warning signals . Predation the mortality involved in training predators to avoid them, and he backed up his arguments with a mathematical model in which predators attack a fixed number (n) of each Introduction distinct unpalatable type in a given season before avoiding them. Here, I review what has since been discovered about In footnote to a letter written in 1860 from Alfred Russel Müllerian mimicry and consider in particular its relation- Wallace to Charles Darwin, Wallace (1860)drewattentionto ship to other forms of mimicry. Müller’s specific model of a phenomenon that he simply could not understand: “P.S. associative learning involving a “fixed n” in a given season ‘Natural Selection’ explains almost everything in Nature, but has not been supported, and several experiments now there is one class of phenomena I cannot bring under it,—the suggest that two distinct unpalatable prey types may be repetition of the forms and colours of animals in distinct just as easy to learn to avoid as one. -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Developing Methods for the Field Survey and Monitoring of Breeding Short-Eared Owls (Asio Flammeus) in the UK: Final Report from Pilot Fieldwork in 2006 and 2007

BTO Research Report No. 496 Developing methods for the field survey and monitoring of breeding Short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) in the UK: Final report from pilot fieldwork in 2006 and 2007 A report to Scottish Natural Heritage Ref: 14652 Authors John Calladine, Graeme Garner and Chris Wernham February 2008 BTO Scotland School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA Registered Charity No. SC039193 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF APPENDICES...........................................................................................................vi SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... viii CRYNODEB............................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................xvi 1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS...........................................................................................2 -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

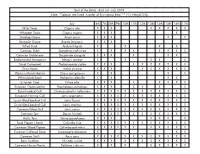

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Eurasian Collared-Doves in Ohio: the Background Coverage

Birdin" the Pits these types ol pits m southwestern Ohio al~ne, and less tha~1 5% get any 61.rdmg Eurasian Collared-doves in Ohio: The Background coverage. tfwe are finding blue grosbeaks m most of the pits that do get birder coverage. then how many are there in the hundreds of~it~ that don 't? . by Bill Whan Two other rare Ohio species have shown an affiliation to gravel pits m 223 E. Tulane Rd. southwestern Ohio. Lark sparrows, an accidental species in Ohio away from Columbus, OH 43202 Oak Openings, have been reported breeding or presum~d breeding at th.ree . southwestern Ohio locations since 1980. On two occasions they were discovered m [email protected] gravel pits. In J 987 a pair nes t e~ in the Mt. Nebo g r ~v~ l pit near Shawnee Lookout Park in Hamilton County. A patr was seen there again m 1990 but was not The Eurasian collared-dove Streplopelia decaoc/o has made history confinned breeding. ln late May and early June of2004 a lark sparrow was present in lands far beyond its likely origins in India. Sri Lanka. and Myanmar. Its at the Roxanna-New Burlington gravel pit and seen by many birders who came present range in North America is already as extensive as that for the rock to see the brown pelican. The third site, as mentioned before. was along a newly pigeon Columbo /ivia, and it has occupied its adopted territory far more constructed section of Blue Rock Rd. in Hamilton County. a site that exhibited quickly. -

Polymorphism Under Apostatic

Heredity (1984), 53(3), 677—686 1984. The Genetical Society of Great Britain POLYMORPHISMUNDER APOSTATIC AND APOSEMATIC SELECTION VINTON THOMPSON Department of Biology, Roosevelt University, 430 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60805 USA Received31 .i.84 SUMMARY Selection for warning colouration in well-defended species should lead to a single colour form in each local population, but some species are locally polymor- phic for aposematic colour forms. Single-locus two-allele models of frequency- dependent selection indicate that combined apostatic and aposematic selection may maintain stable polymorphism for one, two or three aposematic forms, provided that at least one form is subject to net apostatic selection. Frequency- independent selective differences between colour forms broaden the possibilities for aposematic polymorphism but lead to monomorphism if too large. Concurrent apostatic and aposematic selection may explain polymorphism for warning colouration in a number of jumping or moderately unpalatable insects. 1. INTRODUCTION Polymorphism for warning colouration poses a paradox for evolutionists because, as Fisher (1958) seems to have been the first to note, selection for warning colouration (aposematic selection) should lead to monomorphism. Under aposematic selection predators tend to avoid previously encountered phenotypes of undesirable prey, so that the fitness of each phenotype increases as it becomes more common. Given the presence of two forms, each will suffer at the hands of predators conditioned to avoid the other and one will eventually prevail because as soon as it gets the upper hand numerically it will drive the other to extinction. Nonetheless, many species are polymorphic for colour forms that appear to be aposematic. The ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae) furnish a number of particularly striking examples (Hodek, 1973; and see illustration in Ayala, 1978). -

Attraction of Nocturnally Migrating Birds to Artificial Light the Influence

Biological Conservation 233 (2019) 220–227 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Attraction of nocturnally migrating birds to artificial light: The influence of colour, intensity and blinking mode under different cloud cover conditions T ⁎ Maren Rebkea, , Volker Dierschkeb, Christiane N. Weinera, Ralf Aumüllera, Katrin Hilla, Reinhold Hilla a Avitec Research GbR, Sachsenring 11, 27711 Osterholz-Scharmbeck, Germany b Gavia EcoResearch, Tönnhäuser Dorfstr. 20, 21423 Winsen (Luhe), Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: A growing number of offshore wind farms have led to a tremendous increase in artificial lighting in the marine Continuous and intermittent light environment. This study disentangles the connection of light characteristics, which potentially influence the Light attraction reaction of nocturnally migrating passerines to artificial illumination under different cloud cover conditions. In a Light characteristics spotlight experiment on a North Sea island, birds were exposed to combinations of light colour (red, yellow, Migrating passerines green, blue, white), intensity (half, full) and blinking mode (intermittent, continuous) while measuring their Nocturnal bird migration number close to the light source with thermal imaging cameras. Obstruction light We found that no light variant was constantly avoided by nocturnally migrating passerines crossing the sea. The number of birds did neither differ between observation periods with blinking light of different colours nor compared to darkness. While intensity did not influence the number attracted, birds were drawn more towards continuous than towards blinking illumination, when stars were not visible. Red continuous light was the only exception that did not differ from the blinking counterpart. Continuous green, blue and white light attracted significantly more birds than continuous red light in overcast situations. -

Endangered and Threatened Species

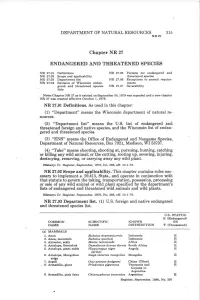

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

Variation in the Procoracoid Foramen in the Accipitridae

Z6f Riv. Hal. Orn., Milano, 57 (3-4): 161-184, 15-XII-19B7 STORRS L. OLSON (*) VARIATION IN THE PROCORACOID FORAMEN IN THE ACCIPITRIDAE Abstract. — The procoracoid foramen of the eoracoid is present in the great majority of genera of Accipitridae. It may be nearly or completely absent in indivi- duals of Circus and Harpagus, the taxonomic significance of which is uncertain. The procoracoid foramen is invariably absent in the genus Accipiter, although the con- dition is still unknown in Erythrotriorchis and Megatriorchis which have sometimes been synonymized with Accipiter. The presence of a well developed procoracoid fo- ramen in Urotriorchis suggests that this genus may not be as closely related to Accipiter as has been assumed. Riassunto. — Variazione nel forame procoracoideo degli Accipitridae. II forame procoracoideo del coraeoide e presente nella maggioranza del generi degli Accipitridi. Esso puo essere quasi o completamente assente in individui di Circus e di Harpagus, fatto dal significato tassonomico incerto. II forame procora- coideo e invariabilmente assente nel genere Accipiter, sebbene tale condizione sia an- cora sconosciuta per i generi Erythrotriorchis e Megatriorchis, a volte posti in sino- nimia con Accipiter. La presenza di un forame procoracoideo ben sviluppato in Uro- triorchis suggerisce che questo genere possa non essere cosi strettamente affine ad Accipiter, come e stato ritenuto. Anatomical characters that may be of use in defining natural sub- divisions of the large and complex family Accipitridae are much to be desired, as, for example, the fused condition of the phalanges of the inner toe (OLSON 1982). Another feature that shows significant variation in the family is the procoracoid process of the eoracoid, the condition of which is worth documenting not just for systematic information but also for purposes of identification of archeological and paleontological materials.