The Growth of the Neurocranium: Literature Review and Implications in Cranial Repair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Can I Learn from a Skull? Animal Skulls Have Evolved for Millions of Years to Protect Vertebrate’S Brains and Sensory Organs

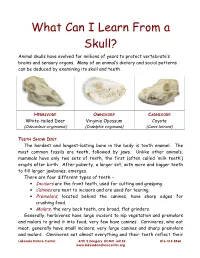

What Can I Learn From a Skull? Animal skulls have evolved for millions of years to protect vertebrate’s brains and sensory organs. Many of an animal’s dietary and social patterns can be deduced by examining its skull and teeth. HERBIVORE OMNIVORE CARNIVORE White-tailed Deer Virginia Opossum Coyote (Odocoileus virginianus) (Didelphis virginiana) (Canis latrans) TEETH SHOW DIET . The hardest and longest-lasting bone in the body is tooth enamel. The most common fossils are teeth, followed by jaws. Unlike other animals, mammals have only two sets of teeth, the first (often called ‘milk teeth’) erupts after birth. After puberty, a larger set, with more and bigger teeth to fill larger jawbones, emerges. There are four different types of teeth – • Incisors are the front teeth, used for cutting and grasping. • Canines are next to incisors and are used for tearing. • Premolars , located behind the canines, have sharp edges for crushing food. • Molars , the very back teeth, are broad, flat grinders. Generally, herbivores have large incisors to nip vegetation and premolars and molars to grind it into food; very few have canines. Carnivores, who eat meat, generally have small incisors, very large canines and sharp premolars and molars. Omnivores eat almost everything and their teeth reflect their Lakeside Nature Center 4701 E Gregory, KCMO 64132 816-513-8960 www.lakesidenaturecenter.org preferences; they have all four types of teeth. In fact, if you’d like to see an excellent example of an omnivore’s teeth, look in the mirror. EYE PLACEMENT IDENTIFIES PREDATORS . Carnivores generally have large eyes, placed so that the eyes look forward and the areas of vision of the two eyes overlap. -

PE2812 Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time

Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time Children who have broken arm bones are at higher risk for breaking the same arm bones again if they do not go through the right treatment, for the right amount of time. How likely is it that There is up to a 5% chance (1 out of every 20 cases) of breaking forearm my child’s arm bones a second time, in the same place. There is a higher risk to break these bones again if the first fracture is in the middle of the forearm bones (as bones will break seen in the pictures below). There is a lower risk if the fracture is closer to again? the hand. Most repeat fractures tend to happen within six months after the first injury heals. First fracture Same fracture after healing for about 6 weeks 1 of 2 To Learn More Free Interpreter Services • Orthopedics and Sports Medicine • In the hospital, ask your nurse. 206-987-2109 • From outside the hospital, call the • Ask your child’s healthcare provider toll-free Family Interpreting Line, 1-866-583-1527. Tell the interpreter • seattlechildrens.org the name or extension you need. Breaking Arm Bones a Second Time How can I help my Wearing a cast for at least six weeks lowers the risk of breaking the same child lower the risk arm bones again. After wearing a cast, we recommend your child wear a brace for 4 weeks in order to protect the injured area and start improving of having a wrist movement. While your child wears a brace, we recommend they do repeated bone not participate in contact sports (e.g., soccer, football or dodge ball). -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

6. the Pharynx the Pharynx, Which Forms the Upper Part of the Digestive Tract, Consists of Three Parts: the Nasopharynx, the Oropharynx and the Laryngopharynx

6. The Pharynx The pharynx, which forms the upper part of the digestive tract, consists of three parts: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx and the laryngopharynx. The principle object of this dissection is to observe the pharyngeal constrictors that form the back wall of the vocal tract. Because the cadaver is lying face down, we will consider these muscles from the back. Figure 6.1 shows their location. stylopharyngeus suuperior phayngeal constrictor mandible medial hyoid bone phayngeal constrictor inferior phayngeal constrictor Figure 6.1. Posterior view of the muscles of the pharynx. Each of the three pharyngeal constrictors has a left and right part that interdigitate (join in fingerlike branches) in the midline, forming a raphe, or union. This raphe forms the back wall of the pharynx. The superior pharyngeal constrictor is largely in the nasopharynx. It has several origins (some texts regard it as more than one muscle) one of which is the medial pterygoid plate. It assists in the constriction of the nasopharynx, but has little role in speech production other than helping form a site against which the velum may be pulled when forming a velic closure. The medial pharyngeal constrictor, which originates on the greater horn of the hyoid bone, also has little function in speech. To some extent it can be considered as an elevator of the hyoid bone, but its most important role for speech is simply as the back wall of the vocal tract. The inferior pharyngeal constrictor also performs this function, but plays a more important role constricting the pharynx in the formation of pharyngeal consonants. -

98796-Anatomy of the Orbit

Anatomy of the orbit Prof. Pia C Sundgren MD, PhD Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Sweden Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lay-out • brief overview of the basic anatomy of the orbit and its structures • the orbit is a complicated structure due to its embryological composition • high number of entities, and diseases due to its composition of ectoderm, surface ectoderm and mesoderm Recommend you to read for more details Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 3 x 3 Imaging technique 3 layers: - neuroectoderm (retina, iris, optic nerve) - surface ectoderm (lens) • CT and / or MR - mesoderm (vascular structures, sclera, choroid) •IOM plane 3 spaces: - pre-septal •thin slices extraconal - post-septal • axial and coronal projections intraconal • CT: soft tissue and bone windows 3 motor nerves: - occulomotor (III) • MR: T1 pre and post, T2, STIR, fat suppression, DWI (?) - trochlear (IV) - abducens (VI) Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Superior orbital fissure • cranial nerves (CN) III, IV, and VI • lacrimal nerve • frontal nerve • nasociliary nerve • orbital branch of middle meningeal artery • recurrent branch of lacrimal artery • superior orbital vein • superior ophthalmic vein Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. -

Morphology of the Foramen Magnum in Young Eastern European Adults

Folia Morphol. Vol. 71, No. 4, pp. 205–216 Copyright © 2012 Via Medica O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl Morphology of the foramen magnum in young Eastern European adults F. Burdan1, 2, J. Szumiło3, J. Walocha4, L. Klepacz5, B. Madej1, W. Dworzański1, R. Klepacz3, A. Dworzańska1, E. Czekajska-Chehab6, A. Drop6 1Department of Human Anatomy, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland 2St. John’s Cancer Centre, Lublin, Poland 3Department of Clinical Pathomorphology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland 4Department of Anatomy, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland 5Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences, Behavioural Health Centre, New York Medical College, Valhalla NY, USA 6Department of General Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland [Received 21 July 2012; Accepted 7 September 2012] Background: The foramen magnum is an important anatomical opening in the base of the skull through which the posterior cranial fossa communicates with the vertebral canal. It is also related to a number of pathological condi- tions including Chiari malformations, various tumours, and occipital dysplasias. The aim of the study was to evaluate the morphology of the foramen magnum in adult individuals in relation to sex. Material and methods: The morphology of the foramen magnum was evalu- ated using 3D computer tomography images in 313 individuals (142 male, 171 female) aged 20–30 years. Results: The mean values of the foramen length (37.06 ± 3.07 vs. 35.47 ± ± 2.60 mm), breadth (32.98 ± 2.78 vs. 30.95 ± 2.71 mm) and area (877.40 ± ± 131.64 vs. -

The Skull O Neurocranium, Form and Function O Dermatocranium, Form

Lesson 15 ◊ Lesson Outline: ♦ The Skull o Neurocranium, Form and Function o Dermatocranium, Form and Function o Splanchnocranium, Form and Function • Evolution and Design of Jaws • Fate of the Splanchnocranium ♦ Trends ◊ Objectives: At the end of this lesson, you should be able to: ♦ Describe the structure and function of the neurocranium ♦ Describe the structure and function of the dermatocranium ♦ Describe the origin of the splanchnocranium and discuss the various structures that have evolved from it. ♦ Describe the structure and function of the various structures that have been derived from the splanchnocranium ♦ Discuss various types of jaw suspension and the significance of the differences in each type ◊ References: ♦ Chapter: 9: 162-198 ◊ Reading for Next Lesson: ♦ Chapter: 9: 162-198 The Skull: From an anatomical perspective, the skull is composed of three parts based on the origins of the various components that make up the final product. These are the: Neurocranium (Chondocranium) Dermatocranium Splanchnocranium Each part is distinguished by its ontogenetic and phylogenetic origins although all three work together to produce the skull. The first two are considered part of the Cranial Skeleton. The latter is considered as a separate Visceral Skeleton in our textbook. Many other morphologists include the visceral skeleton as part of the cranial skeleton. This is a complex group of elements that are derived from the ancestral skeleton of the branchial arches and that ultimately gives rise to the jaws and the skeleton of the gill -

MORPHOMETRIC and MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of FORAMEN OVALE in DRY HUMAN SKULLS Ashwini

International Journal of Anatomy and Research, Int J Anat Res 2017, Vol 5(1):3547-51. ISSN 2321-4287 Original Research Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2017.109 MORPHOMETRIC AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF FORAMEN OVALE IN DRY HUMAN SKULLS Ashwini. N.S *1, Venkateshu. K.V 2. *1 Assistant Professor, Department Of Anatomy,Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College ,Tamaka, Kolar, Karnataka, India. 2 Professor And Head, Department Of Anatomy ,Sri Devaraj Urs Medical College, Tamaka, Kolar, India. ABSTRACT Introduction: Foramen ovale is an important foramen in the middle cranial fossa. Foramen ovale is situated in the greater wing of sphenoid bone, posterior to the foramen rotandum. Through the foramen ovale the mandibular nerve, accessory meningeal artery, lesser petrosal nerve, emissary veins pass .The shape of the foramen ovale is usually oval compared to other foramen of the skull. Materials and Methods: The study was conducted on 55 dry human skulls(110 sides) in Department of Anatomy, Sri Devaraj Urs Medical college, Tamaka, Kolar. Skulls in poor condition or skulls with partially damaged surroundings around the foramen ovale were excluded from the study. Linear measurements were taken on right and left sides of foramen ovale using divider and meter rule. Results: The maximum length of foramen ovale was 14 mm on the right side and 17 mm on the left, its maximum breadth on the right side was 8mm and 10mm on the left . Through the statistical analysis of morphometric measurements between right and left foramen ovale which was found to be insignificant , the results of both sides marks as the evidence of asymmetry in the morphometry of the foramen ovale. -

Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y European Association of Neurooncology Magazine 2014; 4 (2) 71-74

Volume 4 (2014) // Issue 2 // e-ISSN 2224-3453 European Association of NeuroOncology Magazine Neurology · Neurosurgery · Medical Oncology · Radiotherapy · Paediatric Neuro- oncology · Neuropathology · Neuroradiology · Neuroimaging · Nursing · Patient Issues Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Mitsuya K, Nakasu Y European Association of NeuroOncology Magazine 2014; 4 (2) 71-74 Homepage www.kup.at/ journals/eano/index.html Online Database Featuring Author, Key Word and Full-Text Search Member of the THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF NEUROONCOLOGY Indexed in EMBASE Krause & Pachernegg GmbH . VERLAG für MEDIZIN und WIRTSCHAFT . A-3003 Gablitz, Austria Metastatic Skull Tumours Metastatic Skull Tumours: Diagnosis and Management Koichi Mitsuya, Yoko Nakasu Abstract: Metastases of the skull are classifi ed Magnetic resonance imaging is the primary diag- skull metastasis. Surgery is indicated in selected into 2 anatomical groups, presenting distinct clin- nostic tool. Skull metastasis is a focal lesion with patients with good performance status who need ical features. One is calvarial metastasis, which a low-intensity signal on T1-weighted images. En- immediate decompression, cosmetic recovery, or is usually asymptomatic but may cause dural in- hanced T1-weighted images with fat-suppression histological diagnosis. Eur Assoc NeuroOncol vasion, dural sinus occlusion, or cosmetic prob- show tumour, dural infi ltration, and cranial nerve Mag 2014; 4 (2): 71–4. lems. The other is skull-base metastasis, which involvements. Irradiation is the effective and fi rst- presents with cranial-nerve involvement leading line therapy for most skull metastases. Chemo- to devastating symptoms. A high index of suspi- therapy or hormonal therapy is applied depending cion based on new-onset cranial nerve defi cits on tumour sensitivity. -

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy Skull Osteology • This is a comprehensive guide of all the skull features you must know by the practical exam. • Many of these structures will be presented multiple times during upcoming labs. • This PowerPoint Handout is the resource you will use during lab when you have access to skulls. Mind, Brain & Behavior 2021 Osteology of the Skull Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Ethmoid Slide 3 Paranasal Sinuses Slide 19 Vomer, Nasal Bone, and Inferior Turbinate (Concha) Slide4 Paranasal Sinus Imaging Slide 20 Lacrimal and Palatine Bones Slide 5 Paranasal Sinus Imaging (Sagittal Section) Slide 21 Zygomatic Bone Slide 6 Skull Sutures Slide 22 Frontal Bone Slide 7 Foramen RevieW Slide 23 Mandible Slide 8 Skull Subdivisions Slide 24 Maxilla Slide 9 Sphenoid Bone Slide 10 Skull Subdivisions: Viscerocranium Slide 25 Temporal Bone Slide 11 Skull Subdivisions: Neurocranium Slide 26 Temporal Bone (Continued) Slide 12 Cranial Base: Cranial Fossae Slide 27 Temporal Bone (Middle Ear Cavity and Facial Canal) Slide 13 Skull Development: Intramembranous vs Endochondral Slide 28 Occipital Bone Slide 14 Ossification Structures/Spaces Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 15 Intramembranous Ossification: Fontanelles Slide 29 Structures/Apertures Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 16 Intramembranous Ossification: Craniosynostosis Slide 30 Nasal Septum Slide 17 Endochondral Ossification Slide 31 Infratemporal Fossa & Pterygopalatine Fossa Slide 18 Achondroplasia and Skull Growth Slide 32 Ethmoid • Cribriform plate/foramina