'Most Abysmal Thought': the Experience of Eternal Recurrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voronina, "Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's the Flame of Eternity

Volume 8, No 1, Spring 2013 ISSN 1932-1066 Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's The Flame of Eternity Lydia Voronina Boston, MA [email protected] Abstract: Emphasizing romantic tendencies in Nietzsche's philosophy allowed Krzysztof Michalski to build a more comprehensive context for the understanding of his most cryptic philosophical concepts, such as Nihilism, Over- man, the Will to power, the Eternal Return. Describing life in terms of constant advancement of itself, opening new possibilities, the flame which "ignites" human body and soul, etc, also positioned Michalski closer to spirituality as a human condition and existential interpretation of Christianity which implies reliving life and death of Christ as a real event that one lives through and that burns one's heart, i.e. not as leaned from reading texts or listening to a teacher. The image of fire implies constant changing, unrest, never-ending passing away and becoming phases of reality and seems losing its present phase. This makes Michalski's perspective on Nietzsche and his existential view of Christianity vulnerable because both of them lack a sufficient foundation for the sustainable present that requires various constants and makes it possible for life to be lived. Keywords: Nietzsche, Friedrich; life; eternity; spontaneity; spirituality; Romanticism; existential Christianity; death of God; eternal return; overman; time; temporality. People often say that to understand a Romantic you have occurrence of itself through the eternal game of self- to be even a more incurable Romantic or to understand a asserting forces, becomes Michalski's major explanatory mystic you have to be a more comprehensive mystic. -

Engadin ENGLISH EDITION MAGAZINE N MAGIC O

ENGLISH Engadin MAGAZINE No . 3 W I N T E R –––––– 2 0 / 2 1 MAGIC ENGLISH EDITION 2 3 Engadin Winter — 20/21 Dear guests, Ideally we would like to magic you straight over to our valley, Germany but unfortunately we are not able to do that just yet. Instead, you can come to us along a World Heritage railway line of fairy-tale charm, Austria or travel over the bewitching snow-covered mountains with your own SWITZERLAND France GRAUBÜNDEN sleigh. We’re waiting for you: with sparkling powder snow, all kinds of gastronomic wizardry and the purest ice in the world. ENGADIN Italy We wish you happy reading and a good journey – and we look forward to welcoming you here soon! The people of the Engadin Lej da Segl Lej m m m m m m Cover photograph by Filip Zuan Filip by photograph Cover m m m m m Piz Bernina, 4,049 Bernina, Piz Piz Palü, 3,905 Palü, Piz Piz Scerscen, 3,971 Scerscen, Piz 3,937 Roseg, Piz m Map: Rohweder Piz Cambrena, 3,604 Cambrena, Piz Piz Tremoggla, 3,441 Tremoggla, Piz Piz Fora, 3,363 Fora, Piz m m m Piz Lagalb, 2,959 Lagalb, Piz Diavolezza, Diavolezza, 2,978 Piz Led, 3,088 Led, Piz Piz Corvatsch, 3,451 Corvatsch, Piz Diavolezza 3,433 Murtèl, Piz m Lago Bianco Lagalb Piz Lavirun, 3,058 Lavirun, Piz Val Forno Italy Punta Casana, 3,007 Casana, Punta Val Fex Corvatsch Punta Saliente, 3,048 Saliente, Punta Bernina Pass Surlej, 3,188 Piz Val Fedoz Maloja Pass Val Roseg MALOJA Swiss National Park Lej da Silvaplauna SILS SURLEJ ST. -

INTUITION .THE PHILOSOPHY of HENRI BERGSON By

THE RHYTHM OF PHILOSOPHY: INTUITION ·ANI? PHILOSO~IDC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON By CAROLE TABOR FlSHER Bachelor Of Arts Taylor University Upland, Indiana .. 1983 Submitted ~o the Faculty of the Graduate College of the · Oklahoma State University in partial fulfi11ment of the requirements for . the Degree of . Master of Arts May, 1990 Oklahoma State. Univ. Library THE RHY1HM OF PlllLOSOPHY: INTUITION ' AND PfnLoSOPlllC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON Thesis Approved: vt4;;. e ·~lu .. ·~ests AdVIsor /l4.t--OZ. ·~ ,£__ '', 13~6350' ii · ,. PREFACE The writing of this thesis has bee~ a tiring, enjoyable, :Qustrating and challenging experience. M.,Bergson has introduced me to ·a whole new way of doing . philosophy which has put vitality into the process. I have caught a Bergson bug. His vision of a collaboration of philosophers using his intuitional m~thod to correct, each others' work and patiently compile a body of philosophic know: ledge is inspiring. I hope I have done him justice in my description of that vision. If I have succeeded and that vision catches your imagination I hope you Will make the effort to apply it. Please let me know of your effort, your successes and your failures. With the current challenges to rationalist epistemology, I believe the time has come to give Bergson's method a try. My discovery of Bergson is. the culmination of a development of my thought, one that started long before I began my work at Oklahoma State. However, there are some people there who deserv~. special thanks for awakening me from my ' "''' analytic slumber. -

Duration, Temporality and Self

Duration, Temporality and Self: Prospects for the Future of Bergsonism by Elena Fell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire 2007 2 Student Declaration Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that white registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy Department Centre for Professional Ethics Abstract In philosophy time is one of the most difficult subjects because, notoriously, it eludes rationalization. However, Bergson succeeds in presenting time effectively as reality that exists in its own right. Time in Bergson is almost accessible, almost palpable in a discourse which overcomes certain difficulties of language and traditional thought. Bergson equates time with duration, a genuine temporal succession of phenomena defined by their position in that succession, and asserts that time is a quality belonging to the nature of all things rather than a relation between supposedly static elements. But Rergson's theory of duration is not organised, nor is it complete - fragments of it are embedded in discussions of various aspects of psychology, evolution, matter, and movement. My first task is therefore to extract the theory of duration from Bergson's major texts in Chapters 2-4. -

Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences Spring 2007 Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/phi Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kain, P. J. "Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence," The ourJ nal of Nietzsche Studies, 33 (2007): 49-63. Copyright © 2007 The eP nnsylvania State University Press. This article is used by permission of The eP nnsylvania State University Press. http://doi.org/10.1353/nie.2007.0007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence PHILIP J. KAIN I t the center ofNietzsche's vision lies his concept of the "terror and horror A of existence" (BT 3). As he puts it in The Birth of Tragedy: There is an ancient story that King Midas hunted in the forest a long time for the wise Silenus, the companion of Dionysus .... When Silenus at last fell into his hands, the king asked what was the best and most desirable of all things for man. Fixed and immovable, the demigod said not a word, till at last, urged by the king, he gave a shrill laugh and broke out into these words: "Oh, wretched ephemeral race, children of chance and misery, why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. -

Nietzsche for Physicists

Nietzsche for physicists Juliano C. S. Neves∗ Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Instituto de Matemática, Estatística e Computação Científica, CEP. 13083-859, Campinas, SP, Brazil Abstract One of the most important philosophers in history, the German Friedrich Nietzsche, is almost ignored by physicists. This author who declared the death of God in the 19th century was a science enthusiast, especially in the second period of his work. With the aid of the physical concept of force, Nietzsche created his concept of will to power. After thinking about energy conservation, the German philosopher had some inspiration for creating his concept of eternal recurrence. In this article, some influences of physics on Nietzsche are pointed out, and the topicality of his epistemological position—the perspectivism—is discussed. Considering the concept of will to power, I propose that the perspectivism leads to an interpretation where physics and science in general are viewed as a game. Keywords: Perspectivism, Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, Physics 1 Introduction: an obscure philosopher? The man who said “God is dead” (GS §108)1 is a popular philosopher well-regarded world- wide. Nietzsche is a strong reference in philosophy, psychology, sociology and the arts. But did Nietzsche have any influence on natural sciences, especially on physics? Among physi- cists and scientists in general, the thinker who created a philosophy that argues against the Platonism is known as an obscure or irrationalist philosopher. However, contrary to common arXiv:1611.08193v3 [physics.hist-ph] 15 May 2018 ideas, although Nietzsche was critical about absolute rationalism, he was not an irrationalist. Nietzsche criticized the hubris of reason (the Socratic rationalism2): the belief that mankind ∗[email protected] 1Nietzsche’s works are indicated by the initials, with the correspondent sections or aphorisms, established by the critical edition of the complete works edited by Colli and Montinari [Nietzsche, 1978]. -

THE ATROCITY PARADIGM This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Atrocity Paradigm

THE ATROCITY PARADIGM This page intentionally left blank The Atrocity Paradigm A Theory of Evil CLAUDIA CARD 1 2002 3 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2002 by Claudia Card Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Card, Claudia. The atrocity paradigm : a theory of evil / Claudia Card. p. cm. ISBN 0-19-514508-9 1. Good and evil. I. Title. BJ1401 .C29 2002 170—dc21 2001036610 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To my teachers, whose example and encouragement have elicited my best efforts: Ruby Healy Marquardt (1891–1976) Marjorie Glass Pinkerton Marcus George Singer John Rawls Lorna Smith Benjamin This page intentionally left blank Preface Four decades of philosophical work in ethics have engaged me with varieties of evil. It began with an undergraduate honors thesis on punishment, which was followed by a Ph.D. dissertation on that topic, essays on mercy and retribu- tion, and a grant to study the U.S. -

Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting

European Medicines Agency June 1995 CPMP/ICH/377/95 ICH Topic E 2 A Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting Step 5 NOTE FOR GUIDANCE ON CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING (CPMP/ICH/377/95) APPROVAL BY CPMP November 1994 DATE FOR COMING INTO OPERATION June 1995 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 85 75 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 40 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int EMEA 2006 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline 1. INTRODUCTION It is important to harmonise the way to gather and, if necessary, to take action on important clinical safety information arising during clinical development. Thus, agreed definitions and terminology, as well as procedures, will ensure uniform Good Clinical Practice standards in this area. The initiatives already undertaken for marketed medicines through the CIOMS-1 and CIOMS-2 Working Groups on expedited (alert) reports and periodic safety update reporting, respectively, are important precedents and models. However, there are special circumstances involving medicinal products under development, especially in the early stages and before any marketing experience is available. Conversely, it must be recognised that a medicinal product will be under various stages of development and/or marketing in different countries, and safety data from marketing experience will ordinarily be of interest to regulators in countries where the medicinal product is still under investigational-only (Phase 1, 2, or 3) status. -

Recent Ice Trends in Swiss Mountain Lakes: 20-Year Analysis of MODIS Imagery

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Recent Ice Trends in Swiss Mountain Lakes: 20-year Analysis of MODIS Imagery Manu Tom 1,2,3 · Tianyu Wu 1 · Emmanuel Baltsavias 1 · Konrad Schindler 1 Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract Depleting lake ice can serve as an indicator products. We find a change in Complete Freeze Dura- for climate change, just like sea level rise or glacial re- tion of -0.76 and -0.89 days per annum for lakes Sils and treat. Several Lake Ice Phenological (LIP) events serve Silvaplana, respectively. Furthermore, we observe plau- as sentinels to understand the regional and global cli- sible correlations of the LIP trends with climate data mate change. Hence, it is useful to monitor long-term measured at nearby meteorological stations. We notice lake freezing and thawing patterns. In this paper we re- that mean winter air temperature has negative correla- port a case study for the Oberengadin region of Switzer- tion with the freeze duration and break-up events, and land, where there are several small- and medium-sized positive correlation with the freeze-up events. Addition- mountain lakes. We observe the LIP events, such as ally, we observe strong negative correlation of sunshine freeze-up, break-up and ice cover duration, across two during the winter months with the freeze duration and decades (2000-2020) from optical satellite images. We break-up events. analyse time-series of MODIS imagery by estimating spatially resolved maps of lake ice for these Alpine Keywords lake ice monitoring · machine learning · lakes with supervised machine learning (and addition- semantic segmentation · satellite image processing · ally cross-check with VIIRS data when available). -

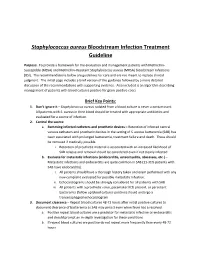

Staphylococcus Aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline

Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline Purpose: To provide a framework for the evaluation and management patients with Methicillin- Susceptible (MSSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI). The recommendations below are guidelines for care and are not meant to replace clinical judgment. The initial page includes a brief version of the guidance followed by a more detailed discussion of the recommendations with supporting evidence. Also included is an algorithm describing management of patients with blood cultures positive for gram-positive cocci. Brief Key Points: 1. Don’t ignore it – Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a blood culture is never a contaminant. All patients with S. aureus in their blood should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and evaluated for a source of infection. 2. Control the source a. Removing infected catheters and prosthetic devices – Retention of infected central venous catheters and prosthetic devices in the setting of S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with prolonged bacteremia, treatment failure and death. These should be removed if medically possible. i. Retention of prosthetic material is associated with an increased likelihood of SAB relapse and removal should be considered even if not clearly infected b. Evaluate for metastatic infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscesses, etc.) – Metastatic infections and endocarditis are quite common in SAB (11-31% patients with SAB have endocarditis). i. All patients should have a thorough history taken and exam performed with any new complaint evaluated for possible metastatic infection. ii. Echocardiograms should be strongly considered for all patients with SAB iii. All patients with a prosthetic valve, pacemaker/ICD present, or persistent bacteremia (follow up blood cultures positive) should undergo a transesophageal echocardiogram 3. -

The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales

Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, 17-22 January 1993, Anaheim, California if ~ THE RELATIONSHIP OF DROUGHT FREQUENCY AND DURATION TO TIME SCALES Thomas B. McKee, Nolan J. Doesken and John Kleist Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 1.0 INTRODUCTION Five practical issues become important in any analysis of drought. These include: 1) time scale, 2) The definition of drought has continually been probability, 3) precipitation deficit, 4) application of the a stumbling block for drought monitoring and analysis. definition to precipitation and to the five water supply Wilhite and Glantz (1985) completed a thorough review variables, and 5) the relationship of the definition to the of dozens of drought definitions and identified six impacts of drought. Frequency, duration and intensity overall categories: meteorological, climatological, of drought all become functions that depend on the atmospheric, agricultural, hydrologic and water implicitly or explicitly established time scales. Our management. Dracup et al. (1980) also reviewed experience in providing drought information to a definitions. All points of view seem to agree that collection of decision makers in Colorado is that they drought is a condition of insufficient moisture caused have a need for current conditions expressed in terms by a deficit in precipitation over some time period. of probability, water deficit, and water supply as a Difficulties are primarily related to the time period over percent of average using recent climatic history (the which deficits accumulate and to the connection of the last 30 to 100 years) as the basis for comparison. No deficit in precipitation to deficits in usable water single drought definition or analysis method has sources and the impacts that ensue. -

Walter Kaufmann

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction walter kaufmann was born in Freiburg in Breisgau, Germany, on July 1, 1921, and died in Princeton, New Jersey, on September 4, 1980, far too young, at fifty‑nine, for someone of his vitality.1 His colleague, the Princeton histo‑ rian Carl Schorske, remained lucid until his death in 2015, after having cel‑ ebrated his one‑hundredth birthday.2 Arthur Szathmary, who together with Walter Kaufmann joined Princeton’s Department of Philosophy in 1947, died in 2013 at ninety‑seven; and Joseph Frank, emeritus professor of compara‑ tive literature at Princeton, with whom Walter debated an understanding of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, passed away in 2013 at ninety‑four, some months after publishing his last book.3 It is hard to imagine Kaufmann’s sudden death at that age arising from an ordinary illness, and in fact the cir‑ cumstances fit a conception of tragedy—if not his own. According to Walter’s brother, Felix Kaufmann, Walter, while on one of his Faustian journeys of exploration to West Africa, swallowed a parasite that attacked his heart. In the months following, Walter died of a burst aorta in his Princeton home. His death does not fit his own conception of tragedy, for his bookThe Faith of a Heretic contains the extraordinary sentences: When I die, I do not want them to say: Think of all he still might have done.