SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT- FISHERIES No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Food and Drink Experiences

MORECAMBE BAY SENSE OF PLACE . TOOLKIT Local Food and Drink Everyone loves to try the local delicacies when on holiday, and it’s important to visitors that these food experiences are authentic. Morecambe Bay has great food to offer that is both connected to the landscape and fun to experience. One thing is for sure, the pubs and cafes around Morecambe Bay are very popular, and the perfect complement to a hard days exploring. “In Morecambe Bay I love to spend a day visiting craft fairs in small villages, have lunch out followed by a short stroll, and then coffee and cake to end the day.” By supporting local food, you are helping the local economy, and reducing food miles, which is better for the environment. And of course you’ll be giving the visitors what they want - traceability, quality and a great experience. You can support local food by: • Using local products in your menus. • Describe where your food has come from on menus, placemats and websites. • Tell visitors about local food events. • Don’t be afraid to recommend your favourite places to eat (the businesses we know recommended these places in the next section). • Prepare a hamper of local food for guests in self-catering accommodation. • Share traditional recipes that use local produce. • Check out more options in Bay Tourism Association’s Morecambe Bay Food and Drink Trail – download a copy of the leaflet from www.baytourism.co.uk, or order one on 01524 582808 / 582394. FASCINATING FOOD Here are our top 7 local ingredients to promote and celebrate: • Shellfish, particularly cockles, mussels and brown shrimps • Fish, seabass, flukes and salmon • Saltmarsh Lamb • Heritage beef • Apples and pears • Damsons and sloes • Local cheeses 34 © Tony Riden Local Food: It’s all in the Name Our food and drink in Morecambe Bay is linked to the landscape and its inhabitants. -

Gball Front 2

Black Pudding Scotch Egg, Smoked Salmon Cocktail, Grilled Gem, Spiced Apple & Grain Mustard Chutney £5.50 Pickled Cucumber & Marie Rose Sauce £7.00 Cider Glazed Beetroot, Seasonal Melon SMALL PLATES Ham Hock Terrine, & Goats Cheese Salad (v) £6.00 Sundried Tomatoes, Picalilly, Toasted Bread £6.00 Cockle & Mussel Popcorn, Piri Piri Salt & Bacon Mayo £6.00 Potted Shrimp, Brown Butter & Toast £8.00 Soy & Honey Chicken Wings, Sesame Soup of the Day £5.00 Spicy Beef & Pork Meatballs, Seeds & Spring Onions £5.50 Tomato Sauce, Charred Bread £6.00 Golden Ball Platter Sharing Seafood to Share - Smoked Salmon, Black Pudding Scotch Egg, Ham Hock Terrine, Whitebait, Crispy Seabass Beef & Pork Meatballs, Mussel & Cockle Popcorn, Crevettes, Garlic Mayonnaise, Smoked Salmon, Potted Shrimps, Olives & Bread £14.50 Bread & Butter £15.50 Large Plates Fish & Chips, Crushed Peas, Salt & Vinegar Sauce £11.00 Chalk Stream Trout, Seafood Broth & Saffron Potatoes £14.00 GB Burger, 8oz Burger, Bacon, Cheddar, Salad & Chips £12.50 Wild Mushroom Risotto Truffle & Parmesan (v) Sml £8 Lg £12 Fish Pie, Cheddar Cheese Mash & Minted Peas £12.50 Honey Glazed Ham, Fried Egg & Pub Chips £11.50 Chicken Kiev, Hot Pot Potatoes & Broccoli Cheese £14.00 Cheese & Onion Pie, Pub Chips & Spiced , Garlic & Rosemary Lamb Henry Tomato Ketchup (v) £11.50 Truffle Potatoes, Green Beans &. Red Wine Jus £15 .00 Lancashire Sausage, Mash Potato, Seafood Linguini, Prawns, Clams, Mussels, Garlic & Chilli £14.00 Crispy Cabbage & Red Onion Gravy £12.00 6oz Steak Frites, Air Dried Tomato, Roast Mushroom 10oz Ribeye Chips, Air Dried Tomato & Roast Mushroom £19.00 & Chips £14.00. -

8247/6 BFF Schools Guide

British foods raise some intriguing Normans and medieval productivity, and many of questions about our past.Why are we a period our special native foods nation of curry lovers, with a taste for dwindled.There is, piquant pickles next to plainly cooked A more refined native cuisine took root after the however, a reversal of this meats? What made us eat fish and chips? Normans introduced new ingredients and techniques. trend as people shop at Returning Crusaders helped promote exotic flavours farmers’ markets, farm And what on earth is Marmite all about? such as rose-water (still familiar in Turkish Delight), shops, specialists and local The bedrock of our food is the land and sea. Rainfall and almonds and sugar. Expensive spices were kept under shops, looking for fresh, a mild, island climate provide lush pastures for feeding lock-and-key and put into special dishes that come seasonal ingredients and cattle and sheep; our coastline (nobody is more than 75 down to us in such festive foods as Christmas pudding produce such as native miles from the sea) delivers plenty of fish; our copious and mince pies. British meat breeds. fuel has long enabled us to bake and roast; our fields of As well as exploring the cuisines of other cultures, chefs barley and northern climate mean we mostly produce The sixteenth to and home-cooks are now rediscovering recipes from the beer rather than wine. But this, of course, is only part of eighteenth centuries past, to find traditional ways of using native ingredients. the story: our culture has been stirred up by the After losing touch with the land and its produce, we are influence of many cultures over many centuries. -

Coates Family Cookbook-15.Pages

THE COATES FAMILY COOKBOOK THE COATES FAMILY COOKBOOK CONTENTS CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 8 HOUSEKEEPING 9 WEIGHTS, MEASURES, AND TEMPERATURES 13 BASIC STOCKS AND SAUCES 15 FISH STOCK OR FUMET 16 COURT BOUILLON 17 CHICKEN STOCK 18 TOMATO SAUCE 20 PESTO SAUCE 21 CHEESE SAUCE 22 BEURRE BLANC 23 HOLLANDAISE SAUCE 24 MAYONNAISE 25 AIOLI 26 VINAIGRETTE 27 SAUCE BRETONNE 28 SAUCE TARTARE 29 CREME ANGLAISE 30 GRAVY 31 BATTERS 32 BATTER FOR PANCAKES 33 YEAST BATTER 34 TEMPURA BATTER 35 NIBBLES – OR AMUSE-BOUCHES 36 CHEESE STRAWS 37 GOUGERES 38 CHAUSSONS (TURNOVERS) 39 BACON AND CHEDDAR TOASTS 40 SPINACH AND CHEESE TOASTS 41 SESAME PRAWN TOAST 42 Page 2 THE COATES FAMILY COOKBOOK SHRIMP AND SPRING ONION FRITTERS 43 CRAB IN FILO PASTRY WITH GINGER AND LIME 44 WELSH RABBIT 45 FURTHER SUGGESTIONS 46 SOUPS 47 CURRIED PARSNIP SOUP 48 WATERCRESS AND SPRING ONION SOUP 49 SPINACH AND CORIANDER SOUP 50 SOUPE AU PISTOU 51 VICHYSSOISE – A VARIATION 52 FOIE GRAS SOUP 53 TOMATO SOUP 54 HOT AND SOUR CHICKEN NOODLE SOUP 55 THAI SOUP 56 FOIE GRAS AND NOODLE SOUP WITH TRUFFLES 57 CARAMELIZED CAULIFLOWER SOUP 58 TOMATO AND ORANGE SOUP 59 PATES, MOUSSES AND TERRINES 60 SALMON RILLETTES 61 SARDINE RILLETTES 62 BUCKLING PATE 63 CHICKEN LIVER PATE 64 TERRINE DE CAMPAGNE 65 AVOCADO MOUSSE 66 SOUFLEES 67 CHEESE SOUFFLÉ 68 SONJA'S AUSTERITY CHEESE SOUFFLÉ 69 QUICHES 70 ONION QUICHE 71 FRESH TOMATO QUICHE 72 RED PEPPER QUICHE 73 LEEK AND BLUE CHEESE QUICHE 74 LEEK, SMOKED HADDOCK AND CHEDDAR CHEESE QUICHE 75 PISSALADIERE 76 ENTREES AND LUNCH AND SUPPER DISHES 77 SUZIE'S CARAMELIZED -

Loch Ryan Natives No

OYSTERS – – FISH & SHELLFISH – West Mersea Jersey Loch Ryan Cornish plaice grilled, fried or meunière 23.50 Native No1 Rock Native No2 ½ doz 24.00 ½ doz 16.50 ½ doz 30.00 Scottish lobster grilled, Newburg, Thermidor or cold 60.00 Dover sole grilled or meunière 48.00 Beau Brummel Rockefeller Kilpatrick ½ doz 19.50 ½ doz 19.50 ½ doz 19.50 Lemon sole Cubat mushroom duxelle, hollandaise sauce and truffle 28.00 CAVIAR – Halibut grilled or poached 34.00 With buckwheat blinis and sour cream Fisherman’s stew scallop, prawns and gurnard 26.00 Aquitaine Royal Belgian Beluga Goujons, tartar sauce 27.00/48.00 Oscietra Turbot on the bone grilled or poached 55.00 30g 40.00 30g 52.00 30g 160.00 50g 67.50 50g 86.00 50g 268.00 – MEAT AND GRILLS – 125g 165.00 125g 210.00 Surrey Farm fillet of beef 36.00 – CRUSTACEA AND MOLLUSCS – Lamb cutlets, mint jelly 32.00 Lamb kidneys 18.00 Mixed grill 28.00 Whelks 7.50 Potted shrimps cold or warm 14.00 Beef fillet, lamb cutlet, lamb kidney, black pudding, bacon and sausage Native lobster cocktail 35.00 Prawn cocktail 16.00 – GAME – Dressed crab 19.00/28.50 Venison ‘au poivre’ 36.00 Devonshire crab and avocado pear 16.00 Roast teal, celeriac, kale and orange 19.50 – SOUPS – Pheasant breast, Savoy cabbage, bacon and Winter truffle 26.00 Chestnut and apple soup Cream cheese Jammy Dodger 8.50 Beef consommé hot or cold 14.00 Lobster bisque 14.00 – OMELETTES – Smoked salmon 17.50 Caviar 45.00 Lobster and crab 31.00 – SMOKED FISH – – VEGETARIAN – Lincolnshire Eel 18.00 Gigha halibut 18.50/37.00 Wild mushroom, salsify and -

Sea Foods Can Make You Live 10 Years More…

SEA FOODS CAN MAKE YOU LIVE 10 YEARS MORE… FISH!!! When we hear this word, our mouth secretes saliva and makes us feel hungry. Most of us love sea foods and records state that sea foods are being a staple food since ancient times. We take immense pleasure in revealing the secrets about sea foods. Seafood is any form of sea life regarded as food by humans, prominently including fish and shellfish. There are many types of seafood which includes cockle, cuttlefish, loco, mussel, octopus, oyster, periwinkle, lobsters, scallop and many more. Fish is a staple food especially in coastal areas. China is the world’s top seafood consumer, followed by Japan and United States. In US, the most widely served seafood is shrimp, followed by salmon and tuna. Seafood provides essential nutrients to the body which includes vitamins A, B and D as well as omega 3 fatty acids. It is also a rich source of calcium and phosphorus. We were so much interested and the eagerness to know more about seafoods almost killed us, as it showered us with so many unknown secrets. We chose this topic to share what we have gained. It is a vast area which could swell our brain with so much information. We have touched only the surface of seafood. Hope this magazine will give you interest towards this topic and help you gain more information. Editor: Adhikeshavan B Co- Editor: Shangamithra SM NATIONAL NEWS over 250 stalls spread over 7,000 sq m, showcasing a wide range of products. This biennial show, re- Monica V visiting Kochi after a span of 12 years, will provide a The Marine Products Export Development Authority platform for an interaction between Indian exporters (MPEDA) has opened its second signature stall at the and overseas importers of Indian marine products and Cochin International Airport under its ‘Seafood India’ an opportunity for display and sale for manufacturers project launched ten months ago. -

Close up Britain Pics Puzzle Answers

9. Prince William 3. Swan 9. Excalibur 10. Teacup & Saucer 4. Sean Connery 10. Ozzy Osbourne 5. Cricket Stumps Level 4 6. JCB Level 11 1. Policeman’s Hat 7. Concorde 1. Dairy Milk Close Up Britain Pics Puzzle 2. Teapot 8. Liver & Onions 2. Hitchcock Answers 3. London Eye 9. Narrowboat 3. Shepherds Pie - Mediaflex Games 4. Cricket Ball 10. Prince Harry 4. Fox 5. The Gherkin 5. Guy Fawkes Mask Level 1 6. Full English Level 8 6. Duchess Kate 1. Big Ben 7. Thatched Roof 1. Kings College 7. Deerstalker 2. Football 8. Bowler Hat 2. Raven 8. Prince Philip 3. Strawberries 9. One Penny 3. The Shard 9. Aston Martin 4. Red Rose 10. Simon Cowell 4. Spotted Dick 10. Christmas Pud 5. Post Box 5. Red Arrows 6. Sandwich Level 5 6. Glastonbury Level 12 7. Telephone Box 1. Wembley Stadium 7. Mick Jagger 1. Spring Lamb 8. Fish and Chips 2. Scones 8. Toad in the Hole 2. The Mall 9. The Queen 3. David Cameron 9. Windsor Castle 3. Roald Dahl 10. John Lennon 4. Top Hat 10. Cup of Tea 4. Adder 5. Bangers and Mash 5. Straw Boater Level 2 6. Bagpipes Level 9 6. Afternoon Tea 1. Bulldog 7. Adele 1. James Bond 7. Lake Windermere 2. Beer 8. Trifle 2. Mini Cooper 8. Olivier 3. Union Jack 9. Millenium Dome 3. Victoria Sponge 9. Bluebells 4. Pound Coins 10. Royal Ballet 4. Churchill 10. Hampton Court 5. Princess Diana 5. Bakewell Tart 6. Black Cab Level 6 6. Parliament Level 13 7. -

The Omega Factor

THE OMEGA FACTOR Women are obsessed with avoiding every trace of fat but some is vital. The Omega factor is the key and you avoid these essential fatty acids at your peril, says Woman’s complementary health editor Michael van Straten. There are good fats, bad fats and essential fats. Trans fats are the worst and only found in manufactured artificial foods like margarines and are even worse for your heart than animal fats. The best are the liquid fats, rich in Omega-3 and 6 essential fatty acids. You need both but it’s the balance between them that’s important. Our ancestors’ diet provided almost equal amounts of 6 and 3 but modern habits provide twenty times as much Omega-6 as 3 that is a recipe for disaster. The Omega-6 fats come from cheap vegetable oils widely used in the food industry. GRANNY WAS RIGHT When granny insisted that eating fish was good for the children’s brains she was almost right. In fact the human brain needs the Omega-3 fats to grow and function so they’re essential during pregnancy, breast-feeding and infancy. Omega-3s from oily fish are now known to be a vital part of the way the brain transmits messages. Oily fish and seafood used to be a staple part of the diet, even in the poorest communities. London’s East End for instance was famous for jellied eels, cockles, mussels, winkles, potted shrimps, pickled herrings and even oysters. Maybe this was part of the reason for traditional Cockneys being so smart. -

STARTERS Potted Shrimps, Smoked Salmon, Mackerel Pate and Artisan Bread 7.00 Soup of the Day with Warm Bread 5.25 Hangover Hash

STARTERS Potted Shrimps, Smoked Salmon, Mackerel Pate and Artisan Bread 7.00 Soup of the Day with Warm Bread 5.25 Hangover Hash – Duck, Chorizo, Potato, Caramelised Onions, Bacon and Parmesan – topped with Poached Duck Egg 7.25 Two Way Goat’s Cheese with Beetroot Puree, Fennel Marinated Apricots and Pine Nuts 6.50 Roast Flat Mushroom with Pesto, Parma Ham and Parmesan 6.75 Sautéed Chicken Livers with Apple and Walnuts on Toast 7.00 MAINS Catalan Fish Stew (Mixed White Fish, King Prawns, Mussels, Tomatoes, Chorizo, Chilli and Garlic) served with Warm Bread 17.00 Beer Battered Fish of the Day with Chunky Chips, Pea Puree and Tartar Sauce 14.00 8oz Rib Eye Steak with Chunky Chips, Onion Rings, Watercress and Pepper Sauce 22.00 Chicken Caesar Salad – Baby Gem Lettuce, Crispy Parma Ham, Croutons, Anchovies, Parmesan and Caesar Dressing on the Side 14.00 Parmigiana – Rustic Italian Dish of Aubergines, Creamy Béchamel Sauce, Tomato Sauce and Cheese – served with Garlic Bread and Mozzarella Salad 12.75 Beef and Stout Pie with Shortcrust Pastry, Parsley Mashed Potato or Fries, Roasted Vegetables and Jus 14.00 Wild Mushroom, Mascarpone and Pea Risotto with Garlic Bread 11.50 Smoked Haddock Florentine (Haddock Flakes, Spinach and a Creamy Cheese Béchamel Sauce) topped with Poached Egg and served with Fries and Salad 12.95 Fishcakes with Fries, Salad and Tartar Sauce 14.00 OPEN SANDWICHES on Warm Sundried Tomato Bread with Fries 9.00 Bacon, Black Pudding and Poached Egg Fish Fingers with Tartar Sauce Smoked Salmon, Poached Egg and Butter Sauce Bacon and Brie Chicken Bacon and Garlic Mayonnaise Please let us know at the time of ordering of any allergies or intolerances and we will either amend the dish or let you know what is suitable. -

Sample Regional Menus

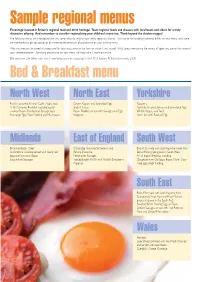

6476_BFF BuyGuide'05 ƒ WEBv 30/6/05 3:28 pm Page 12 Sample regional menus Encourage interest in Britain’s regional food and drink heritage! Team regional foods and cheeses with local beers and ciders for a truly distinctive offering. And remember to consider regionalising your children’s menu too. Think beyond the chicken nugget! The following menus are intended to give you some ideas for making your menu regionally distinct. This may be by including traditional dishes on your menu (and some are mentioned to get you going) or by increasing the emphasis of provenance on your existing menu. Why not mention the breed of sheep used for your roast lamb or the farm on which it was raised? What about mentioning the variety of apple you use or the name of your cheese producer? Specifying provenance on your menu will help make it more distinctive. Did you know £34 billion each year is now being spent on eating out in the UK? (Horizons FS Limited research, 2005) Bed & Breakfast menu North West North East Yorkshire Freshly squeezed Keswick Codlin Apple Juice. Craster Kippers and Scrambled Eggs. Popovers. A full Cumbrian Breakfast including locally- Singin’ Hinnies. Yo r kshire Smoked Salmon and Scrambled Eggs. smoked Bacon, Cumberland Sausage, local Bacon Floddies served with Sausages and Eggs. Whitby Kippers and Toast. free-range Eggs, Black Pudding and Mushrooms. Kedgeree. Yo rk Ham with Poached Egg. Midlands East of England South West Brummie Bacon Cakes. Cambridge Favourite Strawberry and Bucks Fizz made with sparkling wine made from Staffordshire Oatcake served with locally-laid Banana Smoothie. -

Frozen Product List

FROZEN PRODUCT LIST FROZEN AT SEA PACK SIZE 8-16OZ SKINLESS COD FILLET (PBI) 3X15LB 16-32OZ SKINLESS COD FILLET (PBI) 3X15LB 5-8OZ SKINLESS HADDOCK FILLET (PBI) 3X15LB 8-16OZ SKINLESS HADDOCK FILLET (PBI) 3X15LB IQF FILLETS 7-8OZ SKINLESS BONELESS ATLANTIC COD FILLET 4.54KILO 8-10OZ SKINLESS BONELESS COD FILLET 4.54KILO 10-12OZ SKINLESS BONELESS COD FILLET 4.54KILO 7-8OZ COD LOIN 4.54KILO 7-8OZ SKINLESS BONELESS HADDOCK FILLET 4.54KILO 8-10OZ SKINLESS BONELESS HADDOCK FILLET 4.54KILO 7-8OZ PLAICE FILLET 4.54KILO 8-10OZ PLAICE FILLET 4.54KILO 10-12OZ PLAICE FILLET 4.54KILO 8-10OZ BREADED PLAICE 15 PER BOX 8-10OZ LEMON SOLE FILLET 4.54KILO 80-100G SEA BASS FILLET 10 PER BOX 5-6OZ POLLOCK FILLET 4.54KILO 7-8OZ PANGA FILLET 4.54KILO FROZEN SMOKED FISH PACK SIZE SCOTTISH CURED COD STONE SCOTTISH NATURAL SMOKED HADDOCK STONE MANX KIPPERS STONE LOCH FYNE KIPPERS 6KILO BONED KIPPER STONE SMOKED MACKEREL STONE SMALL SMOKED BLOCK STONE COLD WATER PRAWNS 446 ROYAL GREENLAND 5X2KILO 125/175 POLAR 4X2.5KILO 70/90 HOLMES 5X2KILO 125/175 ARCTIC ROYAL (BLACK BAG) 5X2KILO 150/250 ARCTIC ROYAL (BLUE BAG) 5X2KILO 125/175 ARCTIC ROYAL 24X1LB 150/250 CLEAR SEAS 5X2KILO U 150’S GLENMYR 5X2KILO 90/120 COOKED SHELL ON 5KILO 10/20 ARGENTINIAN WILD RED SHRIMP 6X2KILO SCARLET PRAWNS 800G FROZEN PRODUCT LIST WARM WATER PRAWNS PACK SIZE 8/12 ARCTIC ROYAL PEELED DEVEINED TIGER 10X1KILO 16/20 ROYAL STAR PEELED DEVEINED TIGER 10X1KILO 26/30 ROYAL STAR PEELED DEVEINED TIGER 10X1KILO 16/20 ARCTIC ROYAL PEELED DEVEINED KING PRAWN TAIL 10X1KILO 21/25 ARCTIC ROYAL PEELED -

Inverawe Smokehouses WT15 £49.95 INVERAWE SCOTTISH OAK SMOKEHOUSE

THE SIGNATURE BOX 200g Smoked Salmon Sliced Pack 170g Jar Inverawe Dill Sauce INVERAWE 115g Smoked Salmon Pâté AT OUR VERY 120g Duck Pâté with Apricots poached in Cointreau By Appointment to 120g Sliced Roast Smoked Salmon best Her Majesty The Queen 100g Gravadlax Sliced Pack Mail Order Smoked Foods & Hampers 2 x 80g Smoked Salmon Timbale Inverawe Smokehouses WT15 £49.95 INVERAWE SCOTTISH OAK SMOKEHOUSE ALL THE tastes OF SPRING Turn your next meal into a real showstopper Order now by calling 03448 475 490 Visit www.smokedsalmon.co.uk Order lines open Mon-Fri 9am to 7pm | Sat-Sun 9am to 5pm Created to be savoured INV001_80 SPRING 2017 MAILER aw1.indd 1-2 15/03/2017 16:32 A labour of love that goes beyond the normal You may come to us for the unique smoke that flavours our fresh fish, yet the smoke is just the grand finale of our masterful crafting. Our ability to harness every element around us – the environment, the climate, the oak, the brick kilns, the clear waters – sets us apart and creates the authentic smoked salmon that we are recognised for. This belief in a better standard is the hallmark of our history and one that we are proud to serve on your plates. Our award-winning food and exceptional service makes all the difference Throughout our spring selection you will find the very The most exceptional flavours best of Inverawe. Favoured by foodies and customers throughout the country, as well as being praised by are only ever crafted by hand chefs and judges alike.