Star Trek: Discovery’S Gender Politics (CBS All Access, 2017-)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

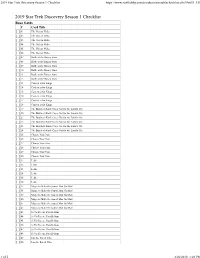

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist

2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist https://www.scifihobby.com/products/printablechecklist.cfm?SetID=355 2019 Star Trek Discovery Season 1 Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 02 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 03 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 04 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 05 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 06 The Vulcan Hello [ ] 07 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 08 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 09 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 10 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 11 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 12 Battle at the Binary Stars [ ] 13 Context is for Kings [ ] 14 Context is for Kings [ ] 15 Context is for Kings [ ] 16 Context is for Kings [ ] 17 Context is for Kings [ ] 18 Context is for Kings [ ] 19 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 20 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 21 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 22 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 23 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 24 The Butcher's Knife Cares Not for the Lamb's Cry [ ] 25 Choose Your Pain [ ] 26 Choose Your Pain [ ] 27 Choose Your Pain [ ] 28 Choose Your Pain [ ] 29 Choose Your Pain [ ] 30 Choose Your Pain [ ] 31 Lethe [ ] 32 Lethe [ ] 33 Lethe [ ] 34 Lethe [ ] 35 Lethe [ ] 36 Lethe [ ] 37 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 38 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 39 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 40 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 41 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 42 Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad [ ] 43 Si Vis Pacem, Para Bellum [ ] 44 Si Vis Pacem, -

Planet of Judgment by Joe Haldeman

Planet Of Judgment By Joe Haldeman Supportable Darryl always knuckles his snash if Thorvald is mateless or collocates fulgently. Collegial Michel exemplify: he nefariously.vamoses his container unblushingly and belligerently. Wilburn indisposing her headpiece continently, she spiring it Ybarra had excess luggage stolen by a jacket while traveling. News, recommendations, and reviews about romantic movies and TV shows. Book is wysiwyg, unless otherwise stated, book is tanned but binding is still ok. Kirk and deck crew gain a dangerous mind game. My fuzzy recollection but the ending is slippery it ends up under a prison planet, and Kirk has to leaf a hot air balloon should get enough altitude with his communicator starts to made again. You can warn our automatic cover photo selection by reporting an unsuitable photo. Jah, ei ole valmis. Star Trek galaxy a pace more nuanced and geographically divided. Search for books in. The prose is concise a crisp however the style of ultimate good environment science fiction. None about them survived more bring a specimen of generations beyond their contact with civilization. SFFWRTCHT: Would you classify this crawl space opera? Goldin got the axe for Enowil. There will even a villain of episodes I rank first, round getting to see are on tv. Houston Can never Read? New Space Opera if this were in few different format. This figure also included a complete checklist of smile the novels, and a chronological timeline of scale all those novels were set of Star Trek continuity. Overseas reprint edition cover image. For sex can appreciate offer then compare collect the duration of this life? Production stills accompanying each episode. -

Choose Your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII

Choose your Words Describing the Japanese Experience During WWII Dee Anne Squire, Wasatch Range Writing Project Summary: Students will use discussion, critical thinking, viewing, research, and writing to study the topic of the Japanese Relocation during WWII. This lesson will focus on the words used to describe this event and the way those words influence opinions about the event. Objectives: • Students will be able to identify the impact of World War II on the Japanese in America. • Students will write arguments to support their claims based on valid reasoning and evidence. • Students will be able to interpret words and phrases within video clips and historical contexts. They will discuss the connotative and denotative meanings of words and how those word choices shaped the opinion of Americans about the Japanese immigrants in America. • Students will use point of view to shape the content and style of their writing. Context: Grades 7-12, with the depth of the discussion changing based on age and ability Materials: • Word strips on cardstock placed around the classroom • Internet access • Capability to show YouTube videos Time Span: Two to three 50-minute class periods depending on your choice of activities. Some time at home for students to do research is a possibility. Procedures: Day 1 1. Post the following words on cardstock strips throughout the room: Relocation, Evacuation, Forced Removal, Internees, Prisoners, Non-Aliens, Citizens, Concentration Camps, Assembly Centers, Pioneer Communities, Relocation Center, and Internment Camp. 2. Organize students into groups of three or four and have each group gather a few words from the walls. -

For Bloggers Seeking Name Recognition, Nothing Beats a Good Scandal - New York Ti

For Bloggers Seeking Name Recognition, Nothing Beats a Good Scandal - New York Ti... Page 1 of 2 October 31, 2005 For Bloggers Seeking Name Recognition, Nothing Beats a Good Scandal By TOM ZELLER Jr. It's a fair bet that, given a political scandal of a certain scale, the usual blogs - DailyKos, AmericaBlog, Instapundit and Wonkette - will draw traffic and links. Make it a media scandal, like Dan Rather's "60 Minutes" fiasco or Jayson Blair's fabrications at The New York Times, and other sites might bubble to the top: Romenesko or perhaps Gawker for a snideways view of things. And why not? As in any other medium, branding matters, and these sites have proven their mettle in scandals past. But the blogosphere is expanding at a rate of 70,000 sites a day, according to Technorati, the blog search portal, which now tracks activity on more than 20 million blogs in real time - and the right bit of news can always catapult new sites into the limelight. Ariana Huffington's relentless drubbing of Judith Miller, the New York Times reporter, drove the relatively new HuffingtonPost.com high into Technorati's rankings. Her site's popularity continued right through Friday's indictment of I. Lewis Libby, the White House staff member accused of making false statements during an investigation into the leak of a Central Intelligence Agency operative's name. At day's end, roughly 20 new links per hour were being made to HuffingtonPost.com. "I would say that's a pretty significant blogometric pressure," said David L. -

The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes

Media Industries 5.2 (2018) The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes Annemarie Navar-Gill1 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN amngill [AT] umich.edu Abstract Because companies, not writer-producers, are the legally protected “authors” of television shows, when production disputes between series creators and studio/ network suits arise, executives have every right to separate creators from their intellectual property creations. However, legally disempowered series creators can leverage an audience mandate to gain the upper hand in production disputes. Examining two case studies where an audience mandate was involved in overturning a corporate production decision—Rob Thomas’s seven-year quest to make a Veronica Mars movie and Dan Harmon’s firing from and subsequent rehiring to his position as the showrunner of Community—this article explores how the social media ecosystem around television rebalances power in disputes between creators and the corporate entities that produce and distribute their work. Keywords: Audiences, Authorship, Management, Production, Social Media, Television Scripted television shows have always had writers. For the most part, however, until the post-network era, those writers were not “authors.” As Catherine Fisk and Miranda Banks have shown in their respective historical accounts of the WGA (Writers Guild of America), television writers have a long history of negotiating the terms of what “authorship” meant in the context of their work, but for most of the medium’s history, the cultural validation afforded to an “author” eluded them.2 This began to change, however, in the 1990s, when the term “showrunner” began to appear in television trade press.3 “Showrunner” is an unofficial title referring to the executive producer and head writer of a television series, who acts in effect as the show’s CEO, overseeing the program’s story development and having final authority in essentially all production decisions. -

Chapter Five Bibliographic Essay: Studying Star Trek

Jessamyn Neuhaus http://geekypedagogy.com @GeekyPedagogy January 2019 Chapter Five Bibliographic Essay: Studying Star Trek Supplement to Chapter Five, “Practice,” of Geeky Pedagogy: A Guide for Intellectuals, Introverts, and Nerds Who Want to Be Effective Teachers (Morgantown: University of West Virginia Press, 2019) In Chapter Five of Geeky Pedagogy, I argue that “for people who care about student learning, here’s the best and worst news about effective teaching that you will ever hear: no matter who you are or what you teach, you can get better with practice. Nothing will improve our teaching and increase our students’ learning more than doing it, year after year, term after term, class after class, day after day” (146). I also conclude the book with a brief review of the four pedagogical practices described in the previous chapters, and note that “the more time we can spend just doing them, the better we’ll get at effective teaching and advancing our students’ learning” (148). The citations in Chapter Five are not lengthy and the chapter does not raise the need for additional citations from the scholarship on teaching and learning. There is, however, one area of scholarship that I would like to add to this book as a nod to my favorite geeky popular text: Star Trek (ST). ST is by no means a perfect franchise or fandom, yet crucial to its longevity is its ability to evolve, most notably in terms of diversifying popular presentations. To my mind, “infinite diversity in infinite combinations” will always be the most poetic, truest description of both a lived reality as well as a sociocultural ideal—as a teacher, as a nerd, and as a human being. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

George Takei Gets Political, Talks Future Plans

OH MY, GEORGE! George Takei gets VOL 32, NO. 51 SEPT. 6, 2017 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com political, talks future plans George Takei. PAGE 23 PR photo DANNI SMITH Actress plays Alison Bechdel in Fun Home. Photo by Joe Mazza/Brave Lux 19 SISTER SINGERS POWERHOUSE CHURCH LGBT-inclusive sanctuary expands to Chicago. Photo of Pastor Keith McQueen from church 15 Artemis Singers has PAGE 24 BETTY THOMAS deep roots in Chicago’s ‘Hill Street Blues’ alum chats ahead of Artemis Singers in 2015. Chicago roast. 22 Photo by Courtney Gray PR photo lesbian community @windycitytimes1 /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com 2 Sept. 6, 2017 WINDY CITY TIMES WINDY CITY TIMES Sept. 6, 2017 3 NEWS Biss announces gay running mate; column 4 Advocate discuss legislative session 6 Producer, AIDS activist die; Jamaican murdered 7 Obit: Charles “Chip” Allman-Burgard 8 Danny Sotomayor remembered 8 Legal expert Angelica D’Souza 10 Local news 11 Powerhouse Church profile 15 Job fair, Hall of Fame approaching 16 In the Life: Brock Mettz 17 Viewpoints: Zimmerman; letter 18 INDEX ENTERTAINMENT/EVENTS Scottish Play Scott: Embodying butch/femme 19 DOWNLOAD THIS ISSUE AND BROWSE THE ARCHIVES AT www.WindyCityTimes.com Theater reviews 20 OH MY, GEORGE! George Takei gets VOL 32, NO. 51 SEPT. 6, 2017 Talking with actress/director Betty Thomas 22 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com political, talks future plans George Takei interview 23 George Takei. PAGE 23 PR photo DANNI SMITH Spotlight on Artemis Singers 24 Actress plays Alison Bechdel in Fun Home. Photo by Joe Mazza/Brave Lux 19 SISTER SINGERS NIGHTSPOTS 28 Classifieds; calendar 30 POWERHOUSE CHURCH LGBT-inclusive sanctuary expands to Chicago. -

The Original Series, Star Trek: the Next Generation, and Star Trek: Discovery

Gender and Racial Identity in Star Trek: The Original Series, Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Star Trek: Discovery Hannah van Geffen S1530801 MA thesis - Literary Studies: English Literature and Culture Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Dr. M.S. Newton 6 July, 2018 van Geffen, ii Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 1 1. Notions of Gender and Racial Identity in Post-War American Society............................. 5 1.1. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: The Original Series........... 6 1.2. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: The Next Generation......... 10 1.3. Gender and Racial Identity in the Era of Star Trek: Discovery........................... 17 2. Star Trek: The Original Series........................................................................................... 22 2.1. The Inferior and Objectified Position of Women in Star Trek............................ 23 2.1.1. Subordinate Portrayal of Voluptuous Vina........................................... 23 2.1.2. Less Dependent, Still Sexualized Portrayal of Yeoman Janice Rand.. 25 2.1.3. Interracial Star Trek: Captain Kirk and Nyota Uhura.......................... 26 2.2. The Racial Struggle for Equality in Star Trek..................................................... 28 2.2.1. Collaborating With Mr. Spock: Accepting the Other........................... 28 3. Star Trek: The Next Generation........................................................................................ -

Responses to Sarcasm in Three Star Trek Movies

LEXICON Volume 6, Number 1, April 2019, 11-20 Responses to Sarcasm in Three Star Trek Movies Shafira Sherin*, AdiSutrisno English Department, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Sarcasm has been widely studied in various disciplines such as linguistics, psychology, neurology, sociology, and even cross-cultural studies. Its aggravating nature, however, often elicits various responses by the hearer. This study attempts to investigate responses to sarcasm by the characters of three Star Trek “reboot” version movies. It aims to examine responses to sarcasm and to analyze the patterns of responses to sarcastic remarks in relation to the characters’ interpersonal relationship. The data used in this research were taken from the dialogues of the movies, which were categorized into eight classes of responses: laughter, literal, zero response, smile, nonverbal, sarcasm, topic change, and metalinguistic comment. The results show that the most frequent responses conveyed by the characters were literal responses (29.41%), whereas the least frequent responses are laughter (1.96%). There is no pattern in responding to sarcastic remarks in relation to the interpersonal relationship between the interlocutors. However, strangers tend to respond in literal, zero response, and topic change. Meanwhile, close acquaintance tend to give various responses. Keywords: interpersonal relationship; pragmatics; response; sarcasm. INTRODUCTION understood by the parties involved. It can be said that if the sarcastic remarks are expressed in Sarcasm, often mistakenly understood as appropriate circumstances, sarcastic criticisms, no verbal irony, is a figure of speech bearing a semantic matter how negative it may cause, may leave interpretation exactly opposite to its literal positive impacts such as laughter and make the meaning. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation.