Praamsma Naomi.Pdf (1.277Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peel Shelter and Housing Support Services

Peel Shelter and Housing Support Services Giving Hope Today Today David Carleton Executive Director November 2014 Letter of Recommendation- Boaden’s Mississauga I am pleased to offer a letter of recommendation for Boaden’s and Organic Kids Catering. PEEL FAMILY Boaden’s and Organic Kids Catering has been a proud partner of the Salvation Army and the SHELTER Peel Family Shelters for many years. 1767 Dundas St. Mississauga, Ontario The reason I say partners and not supplier is that’s exactly what they are. What began as L4X 1L5 business relationship quickly turned into much more. Boaden’s and the Salvation Army have (905) 272-7061 partnered together to provide meals on a daily basis to our various Homeless Shelters in the Peel Region. CAWTHRA RD. SHELTER Boaden’s and Organic Kids Catering provides excellent, quality and most of all delicious meals. 2500 Cawthra Road These are not your typical homeless shelter meals you may think. Boaden’s and Organic Kids Mississauga, Ont. Catering goes beyond this is in the attention detail it puts into each and every meal for our L5A 2X3 residences. They provide us with b, lunch and dinner meals 7 days a week, 365 days a year. (905) 281-1272 Yes they even arrange meals on all holidays. Brampton I have heard quite often how delicious their meals are but from experience (my taste buds) I can attest to this. When our staff and myself enjoy the meals just as much as the clientele that WILKINSON should tell you something. Their meals are meals are you would eat at home. -

The Salvation Army Bahamas Division 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 SALVATION ARMY BAHAMAS DIVISION 2020 TABLE of CONTENTS

The Salvation Army Bahamas Division 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 SALVATION ARMY BAHAMAS DIVISION 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 About The Salvation Army 06 Advisory Board 08 Message from the Chairman 10 Message from the Divisional Commander Service is our watchword, and there is no 12 reward equal to that of doing the most good to Key Stats the most people in the most need. 14 -Evangeline Booth Annual Highlights 16 Financial Statement 18 Our Partners 19 William Booth Society 20 Thrift Shop Donors 21 People Helping People 2 ANNUAL REPORT SALVATION ARMY BAHAMAS DIVISION 2020 SALVATION ARMY BAHAMAS DIVISION 2020 The Army in The Bahamas The administrative offices (or Divisional Headquarters) for The Salvation Army are located on 31 Mackey Street, Nassau. From this location, The Salvation Army coordinates all of its programs and services rendered in The Bahamas. The Divisional Commander is directly responsible for the Army’s work and business in The Bahamas, and is ably supported at Divisional Headquarters by other Salvation Army officers, advisory board members, employees and volunteers. The Salvation Army in The Bahamas falls under the administrative jurisdiction of the Caribbean Territory, with Territorial Headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica. The Salvation Army’s international offices are in London, England, where the General, the Army’s world leader, gives guidance to the organization in 113 countries around the world. How it all got started In 1931 Colonel Mary Booth, then Territorial Commander for The Salvation Army in the Caribbean, was on her way to Bermuda from the Territorial Headquarters in Jamaica when the ship she was sailing in made a brief stop at the port in Nassau. -

The-War-Cry-April-2012.Pdf

Founder From the Editor William Booth General Linda Bond Territorial Commander esus chose to engage with the local community. It cost him - his Commissioner André Cox life, but his gain outweighed all the suffering - Eternal life for you International Headquarters Jand me. 101 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4P 4GP England We go to church - in our community. We shop - in our community. We even attend special events - in our community, but why is it that we do Territorial Headquarters not engage with our community? We pull out of the driveway in the 119 - 121 Rissik Street, morning and zoom to work or jump in the taxi and return in the evening Johannesburg 2001 and we are perhaps oblivious to what is happening around us - in our Editor community. Bill Hybels said: “The local church is the hope of the Captain Wendy Clack world.” If we acknowledge that WE are the church and therefore the Editorial Office hope, because Jesus should be seen in us, then should this Easter time not be a turning point for us as amidst the busyness we remember that P.O. Box 1018 there is a whole wide world out there that is waiting to experience that Johannesburg 2000 hope - in our community. Tel:. (011) 718-6700 Fax: (011) 718-6790 In this edition we look at various places where ordinary people like you E-mail: and me are making a difference and bringing hope by engaging with [email protected] their communities. www.salvationarmy.org.za We bid our Territorial Commanders a farewell as they depart to the Design, Print & United Kingdom as Commissioner André Cox shares his last TC talk Distribution with us. -

History of the Salvation Army Early Beginnings the Salvation Army Is

History of the Salvation Army Early Beginnings The Salvation Army is an international organization, which began humbly in 1865 under the guidance of a radical Methodist minister named William Booth. More than 130 years later, The Salvation Army now stretches across the globe with churches and missions on every continent except Antarctica. With its international headquarters in London, England, The Salvation Army is dedicated to spreading the Gospel of Jesus Christ and ministering whenever and wherever there is need. The Salvation Army was founded by William Booth, an ordained Methodist minister. Aided by his wife Catherine, Booth formed an evangelical group dedicated to preaching among the “unchurched” people living in the midst of appalling poverty in London’s East End. Booth abandoned the conventional concept of church and a pulpit, instead taking is message to the people. His fervor led to disagreement with church leaders in London, who preferred traditional methods. As a result, he withdrew from the church and traveled throughout England, conducting evangelistic meetings. In 1865, William Booth was invited to hold a series of Evangelistic meetings in the East of London. He set up a tent in a Quaker graveyard, and his services became an instant success. This proved to be the end of his wanderings as an independent traveling evangelist. His renown as a religious leader spread throughout London, and he attracted followers who were dedicated to fighting for the souls of men and women. Thieves, prostitutes, gamblers and drunkards were among Booth’s first converts to Christianity. To congregations that were desperately poor, he preached hope and salvation. -

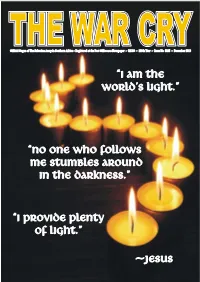

No One Who Follows Me Stumbles Around in the Darkness.”

THE WAR CRY Official Organ of The Salvation Army in Southern Africa ~ Registered at the Post Office as a Newspaper ~ R5.00 ~ 129th Year ~ Issue No 5825 ~ December 2013 “I am the world’s Light.” “No one who follows me stumbles around in the darkness.” “I provide plenty of light.” ~Jesus Founder FROM THE EDITOR William Booth General André Cox Territorial Commander Commissioner W. Langa International Headquarters 101 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4P 4GP England Territorial Headquarters ince moving to Johannesburg last year, I This light is not just for believers - it is for have made it a habit to have candles and everyone, therefore it is important for us to share 119 - 121 Rissik Street, Smatches in every room to be prepared this hope with our neighbours, colleagues and Johannesburg 2001 when the lights go out. After a long day at work, school mates. We would not hide or keep a cure Editor you arrive home, quickly start supper and click, for a disease to ourselves, surely? God brought Captain Wendy Clack the electricity goes off- a familiar event for most the cure for humankind's biggest problem - sin - Editorial Office of you. It takes me time to orientate myself and through Jesus' death on the cross and His P.O. Box 1018 to grope in the dark for the nearest candle to light resurrection. This is the greatest gift you could it. Relief! I can see where I am going again… give anyone this year - give them Jesus, by living Johannesburg 2000 Him and sharing Him. Tel:. (011) 718-6700 There are so many people that still live like this Fax: (011) 718-6790 spiritually - we open the newspapers and watch I have sourced photos from all over the Territory E-mail: the news reports and see that within our country for you to share how Youth and Children, [email protected] young children, the most vulnerable in our Women and men have been sharing this light. -

Central News Pages Feb08

The Salvation Army / USA Central Territory News and Views from the Midwest “We are all one body, we have the same Spirit, and we have all been called to the same glorious future.” Eph. 4:3,4 (NLT) Volume 46, Number 11 Novemberr 2016 “Messengers of the Gospel” welcomed he 24 members of the talked about “These men, with their messen - “Messengers of the Gospel” Christ’s ger bags strapped across their bod - session were greeted by the instruction to ies, were referred to as warrior T monks. They knew they were going territory with a public wel - those people come at the Chicago, Ill., Mayfair He had healed into exile, never to see their home - Community Church (Corps) where to “go tell oth - lands again, but their commitment they—and the rest of those in atten - ers.” Alluding to Christ’s charge was even dance—were issued a challenge by to her visit to stronger,” she continued. “When we guest speaker Commissioner Sue the Trinity received God’s grace, Christ gave Swanson to proclaim the good news College each of us a messenger bag; He of Jesus Christ. Museum in called us to speak up. Where do you need to take your bag?” the Dublin, Ireland, she compared efforts of Irish monks to do likewise Basing her remarks on the fifth commissioner asked. chapter of Mark, the commissioner Christ’s charge to them with the during the Dark Ages. She said the monks painstakingly pre - During the entrance of the new served the Bible by copying its cadets, their officer and soldier text by hand onto parchment mentors were recognized as they sheets, which were then followed them down the center bound not only into the beau - aisle to the foot of the platform to tifully illuminated Book of stand with their divisional leaders Kells on display in the muse - and divisional candidates’ secre - um but also into smaller books taries. -

Central News Pages Feb08

The Salvation Army / USA Central Territory News and Views from the Midwest “We are all one body, we have the same Spirit, and we have all been called to the same glorious future.” Eph. 4:3,4 (NLT) Volume 47, Number 11 December 2017 Love rings true at Christmas by Craig Dirkes Unit. Incredibly, his last name is eral mental disabilities. Winterringer! 45-year-old man is in his “The only reason I’m alive is fourth year of ringing Michael Winterringer has manned because of God,” said Michael, Abells at kettles in the cold the same spot outside the local who celebrated five years of and snow for the Grand Walmart for more than 200 hours sobriety last spring. “There are Rapids, Minn., Service Extension each season—and he’s loved every no words to explain the depths minute of it. of God’s love,” he said, fighting “You know back tears. “It’s better than any that feeling drug. It’s better than any you get when drink.” you fall in love Michael’s lifelong struggle with Jesus? with addiction ended when he That’s the way moved to Grand Rapids and hour for The Salvation Army. I feel when I got involved with a Presbyterian ring bells,” he church in the nearby city of Although ringing bells outside for said. Coleraine. Several members of his eight hours a day is frigid work, Michael said he doesn’t mind the Michael church have been like parents to him, as have members of other cold. In fact, he almost prefers it. -

Spiritual Formation Towards Christ Likeness in a Holiness Context

3377 Bayview Avenue TEL: Toronto, ON 416.226.6620 M2M 3S4 www.tyndale.ca UNIVERSITY Note: This Work has been made available by the authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research and may not be copied or reproduced except as permitted by the copyright laws of Canada without the written authority from the copyright owner. Bond, Linda Christene Diane. "Through the Lens of Grace: Spiritual Formation Towards Christlikeness in a Holiness Context." D. Min., Tyndale University College & Seminary, 2017. Tyndale University College and Seminary Through the Lens of Grace: Spiritual Formation towards Christlikeness in a Holiness Context A Research Portfolio Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Tyndale Seminary by Linda Christene Diane Bond Toronto, Canada July 3, 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Linda Bond All rights reserved ABSTRACT To see life through the lens of grace is to gain a new perspective of how God shapes his children in the image of his Son. Spiritual formation is a process, a journey with God’s people, which calls for faith and participation, but all is of grace. This portfolio testifies to spiritual formation being God’s work. Though our involvement in spiritual disciplines and the nurturing of the Christian community are indispensable, they too are means of grace. The journey of spiritual formation for the individual Christian within the community of faith is explained in the writings of A.W. Tozer as well as the Model of Spiritual Formation in The Salvation Army. The goal is Christlikeness, a goal which requires adversity and suffering to deepen our faith and further our witness. -

Called to Service Officers in the Norwegian Salvation Army

Called to Service Officers in the Norwegian Salvation Army Jens Inge Flataas Master’s Thesis in Comparative Religion Spring 2014 Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion Faculty of Humanities University of Bergen II Called to Service The Norwegian Salvation Army Officer © Jens Inge Flataas. Masters Thesis, University of Bergen, 2014 III Table of Contents Norwegian Summary/Norsk sammendrag V Acknowledgements VI Part I: Background 1 Chapter 1 - The Salvation Army 1 A Brief History of the Salvation Army 1 A Brief Organizational Profile 7 Previous Research 14 Chapter 2 - Leadership and Religion 16 Personal Motivation 16 Strategy 18 Human Resources 21 Spiritual Leadership & Workplace Spirituality 24 Further Perspectives on Religion and Leadership 28 Chapter 3 – Method 34 The Interviewees 34 The Interview Guide 35 Group Interview 37 The Post – Interview Process 40 NSD 41 Part II: Analysis Chapter 4 - Approaching Officership 42 Motivation 42 The Calling 50 Challenging Aspects of Officership 58 Handling Stress 65 Chapter 5 – Strategy 72 Visions 72 Guiding Orders 80 Challenges 83 Individual Strategies 86 Chapter 6 - Human Resources 91 Motivation 91 Work Tasks 97 Use of Resources 100 Guidelines for Human Resource Management 102 Part III: Synthesis 104 Chapter 7 – The Norwegian Salvation Army Officer 104 Suggestions for Further Research 106 Bibliography Appendices IV Norwegian Summary – Norsk sammendrag Denne oppgaven tar for seg frelsesarmeen i Norge. Offiserene i frelsesarmeen fyller en rekke ulike funksjoner i frelsesarmeen, men offisersutdanningen forbereder offiserene til å fungere primært som religiøse- og administrative ledere. Prosjektet baserer seg på en presentasjon av data samlet gjennom intervjuer med tolv individuelle offiserer i tillegg til et gruppeintervju med fire deltakere. -

Moorlands College

WBC Journal Issue 2 February 2020 What kind of leaders does The Salvation Army need to lead its mission in the United Kingdom in the twenty-first century? By Michael Hutchings Abstract This exploration of leadership begins with an analysis of a Pauline perspective on Christian leadership, beginning with the Pastoral Epistles, under the themes of Knowing, Being and Doing. Developing Salvation Army perspectives on leadership are explored and various practical and ecclesiological tensions are identified. An integrated response to the research question begins by summarising of the contemporary mission landscape and acknowledging that The Salvation Army has experienced a period of decline. A number of themes are explored in relation to the required attitudes and activities of contemporary Salvationist leaders. Conclusions demonstrate the need to faithfully re-imagine leadership while acknowledging tensions surrounding the leadership task and remaining true to scripture and the essence of the Army. Introduction In 2013, Commissioner André Cox delivered the keynote address to the Called and Commissioned International Conference on the Training of Cadets. Cox (2014:16) argued that ‘effective leadership is essential if The Salvation Army is to continue fulfilling its unique mission effectively’. He also asked, ‘What kind of leaders do we need to be producing?’ (2014:15). This question, which conflates issues of identity, mission and leadership, is explored in this paper. The research explores this question in terms of officership at corps level and the aim is to identify characteristic attitudes and activities of officers as leaders of twenty- first-century mission; and to acknowledge points of tension which, left unaddressed, could present barriers to effective spiritual leadership in the Army. -

William and Catherine Booth: Did You Know?

Issue 26: William & Catherine Booth: Salvation Army Founders William and Catherine Booth: Did You Know? John D. Waldron, retired Salvation Army commissioner of Canada and Bermuda, is the author or editor of many books on The Salvation Army. William Booth, as a teenager, was a pawnbroker’s apprentice. Catherine Booth experienced long periods of illness as a child, during which she read voraciously, including theological and philosophical books far beyond her years. She read the entire Bible before she was 12. William toured the United States several times in his later years, drawing enormous crowds, and met President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1898 he gave the opening prayer at a session of the U. S. Senate. William was a vegetarian, eating “neither fish, flesh, nor fowl.” The Booths had eight children of their own, yet they adopted a ninth, George, about whose later life little is known. Seven of the Booths’ eight natural children became world-known preachers and leaders—two as general of The Salvation Army. The seven also all published songs that are still sung today. William led the fight against London’s loathsome prostitution of 13- to 16-year-old girls; he collected 393,000 signatures that resulted in legislation aimed at stopping the “white slavery.” The Salvation Army led in the formation of the USO, operating 3,000 service units for the armed forces. William pioneered the mass production of safety matches. The Salvation Army helps more than 2,500,000 families each year through 10,000 centers worldwide. Their resident alcoholic rehabilitation program is the largest in the U.S. -

Virtual Community of Practice?

NOVEMBER 2013-JANUARY 2014 // ISSUE 10 [email protected] Prog A NEWS UPDATE FROM THE PROGRAMME RESOURCES DEPARTMENT AT IHQ Programme Resources Commissioner Gerrit Marseille INTERNATIONAL SECRETARY FOR PROGRAMME RESOURCES What is a Virtual Community of Practice? ast year I had the opportunity What is new is that, in more recent days, to take part in a Project Officer’s the world of education has recognised 1 Programme Resources Conference for the South the value of these groups for informal What is a Virtual American territories, held in learning. In addition, new electronic means Community of Practice? Lima, Peru. The conference of communication have opened up new Lwas ably facilitated by Jo Clark of our possibilities in this area. 3 International International Projects and Development The term ‘Community of Practice’ (CoP) Health Services Section. The meeting was set-up to help was coined in the 1990s: Trained to serve project officers from these territories to ‘CoPs are groups of people who share discuss the issues and challenges they a concern, a set of problems or a passion 4 Photo pages all share. Normally they would be far about a topic and who deepen their apart, wrestling on their own with the knowledge and experience by interacting Projects from around the world complexities of our development work, but on an on-going basis’ (Wenger, 1998). during this week of formal and informal The concept has been implemented by discussions they were able to discover that self-forming teams within organisations, 6 International they were not alone. then across geographical locations.