Final Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. Owyhee Uplands Section

12. Owyhee Uplands Section Section Description The Owyhee Uplands Section is part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion. The Idaho portion, the subject of this review, comprises southwestern Idaho from the lower Payette River valley in the northwest and the Camas Prairie in the northeast, south through the Hagerman Valley and Salmon Falls Creek Drainage (Fig. 12.1, Fig. 12.2). The Owyhee Uplands spans a 1,200 to 2,561 m (4,000 to 8,402 ft) elevation range. This arid region generally receives 18 to 25 cm (7 to 10 in) of annual precipitation at lower elevations. At higher elevations, precipitation falls predominantly during the winter and often as snow. The Owyhee Uplands has the largest human population of any region in Idaho, concentrated in a portion of the section north of the Snake River—the lower Boise and lower Payette River valleys, generally referred to as the Treasure Valley. This area is characterized by urban and suburban development as well as extensive areas devoted to agricultural production of crops for both human and livestock use. Among the conservation issues in the Owyhee Uplands include the ongoing conversion of agricultural lands to urban and suburban development, which limits wildlife habitat values. In addition, the conversion of grazing land used for ranching to development likewise threatens wildlife habitat. Accordingly, the maintenance of opportunity for economically viable Lower Deep Creek, Owyhee Uplands, Idaho © 2011 Will Whelan ranching operations is an important consideration in protecting open space. The aridity of this region requires water management programs, including water storage, delivery, and regulation for agriculture, commercial, and residential uses. -

Idaho Moose Management Plan 2020-2025

Idaho Moose Management Plan 2020-2025 DRAFT December 10, 2019 1 This page intentionally left blank. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Shiras Moose (Alces alces shirasi) occur across much of Idaho, except for the southwest corner of the state. Moose are highly valued by both hunters and non-hunters, providing consumptive and non-consumptive opportunities that have economic and aesthetic value. Over the past century their known range has expanded from small areas of northern and eastern Idaho to their current distribution. Population size also increased during this time, likely peaking around the late 1990s or early 2000s. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) is concerned that current survey data, anecdotal information and harvest data indicate moose have recently declined in parts of Idaho. Several factors may be impacting moose populations both positively and negatively including predation, habitat change (e.g., roads, development, timber harvest), changing climate, disease or parasites and combinations thereof. IDFG was established to preserve, protect, perpetuate and manage all of Idaho’s fish and wildlife. As such, species management plans are written to set statewide management direction to help fulfill IDFG’s mission. Idaho’s prior moose management plan (Idaho Department of Fish and Game 1990) addressed providing a quality hunting experience, the vulnerability of moose to illegal harvest, protecting their habitat, improving controlled hunt drawing odds and expanding moose populations into suitable ranges. The intent of this revision to the 1990 Moose Management Plan is to provide guidance for IDFG and their partners to implement management actions that will aid in protection and management of moose populations in Idaho and guide harvest season recommendations for the next 6 years. -

Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019

Management Plan for the Conservation of Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME July 2014 2 Idaho Department of Fish & Game Recommended Citation: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2014. Management plan for the conservation of wolverines in Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Idaho Department of Fish and Game – Wolverine Planning Team: Becky Abel – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Southeast Region Bryan Aber – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Upper Snake Region Scott Bergen PhD – Senior Wildlife Research Biologist, Statewide, Pocatello William Bosworth – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Rob Cavallaro – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Upper Snake Region Rita D Dixon PhD – State Wildlife Action Plan Coordinator, Headquarters Diane Evans Mack – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, McCall Subregion Sonya J Knetter – Wildlife Diversity Program GIS Analyst, Headquarters Zach Lockyer – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southeast Region Michael Lucid – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Panhandle Region Joel Sauder PhD – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Clearwater Region Ben Studer – Web and Digital Communications Lead, Headquarters Leona K Svancara PhD – Spatial Ecology Program Lead, Headquarters Beth Waterbury – Team Leader & Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Salmon Region Craig White PhD – Regional Wildlife Manager, Southwest Region Ross Winton – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Magic Valley Region Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at fishandgame.idaho.gov/wolverine-conservation-plan Front Cover Photo: Composite photo: Wolverine photo by AYImages; background photo of the Beaverhead Mountains, Lemhi County, Idaho by Rob Spence, Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Program, Wildlife conservation Society. Back Cover Photo: Release of Wolverine F4, a study animal from the Central Idaho Winter Recreation/Wolverine Project, from a live trap north of McCall, 2011. -

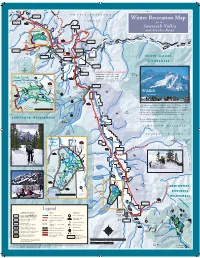

Winter Recreation Map

to Lowman r N 44˚ 18.794’ CHALLIS NATIONAL C W 115˚ 04.023’ p r a C k r n e T w re Winter Recreation Map o k C e G k e FOREST e N 44˚ 18.950’ c e n r o r W 115˚ 05.241’ M s C for the p C m n o l i l s r e n N 44˚ 16.798’ a C n B e W 114˚ 55.578’ k B ee Sawtooth Valley T Cr a w ly s t el in s o V K Cr a d a K L O e a l E e E e k le O and Stanley Basin M ee y E k r R Park C C P C Creek r k e k l e E k Y e L e r L SUNBEAM C E O N ho T I A K o A R N E E R Y Cree R A A y k E C D to Challis r R B N D k N 44˚ 16.018’ O U e ELK e L MOUNTAIN r W 114˚ 55.247’ A C N ey R l I O n A T i v t a N S e r J oe’ W T O O T H e s A B C N G ak re S e u L i k l k k i p c y V g e N 44˚ 15.325’ e N 44˚ 15.30’ N 44˚ 13.988’ h e l a & e n e W 115˚ 02.705’ l W 115˚ 00.02’ W 114˚ 56.006’ r a r t l T C S eek e r y u a C C C c R Stanley Job k n s o in m o k Lake l o l a o u S n E i C g WHITE CLOUDS N 44˚ 15.496’ r s C O U eek h B N D W 115˚ 00.008’ a r S S A N 44˚ 13.953’ e e E R W 114˚ 56.375’ LOWER C C N Y k R r STANLEY e e E l e WILDERNESS k D t t L k i I e e L r W C N 44˚ 13.960’ ed ok k STANLEY W 114˚ 55.200’ ro ee C r k C e McGOWN r e n C PEAK r o at Snowmobile trail mileage from Stanley to: I Go e k re N 44˚ 13.037’ C W 114˚ 55.933’ LOOKOUT Redfish Lake ...................... -

Geology and Mineral Resources of the Randolph Quadrangle, Utah -Wyoming

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 923 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE RANDOLPH QUADRANGLE, UTAH -WYOMING BY G. B. RICHARDSON UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. O. ......... Price 55 cents HALL LIBRARY CONTENTS Pag* Abstract.____________--__-_-_-___-___-_---------------__----_____- 1 Introduction- ____________-__-___---__-_-_---_-_-----_----- -_______ 1 Topography. _____________________________________________________ 3 Bear River Range._.___---_-_---_-.---.---___-___-_-__________ 3 Bear River-Plateau___-_-----_-___-------_-_-____---___________ 5 Bear Lake-Valley..-_--_-._-_-__----__----_-_-__-_----____-____- 5 Bear River Valley.___---------_---____----_-_-__--_______'_____ 5 Crawford Mountains .________-_-___---____:.______-____________ 6 Descriptive geology.______-_____-___--__----- _-______--_-_-________ 6 Stratigraphy _ _________________________________________________ 7 Cambrian system.__________________________________________ 7 Brigham quartzite.____________________________________ 7 Langston limestone.___________________________________ 8 Ute limestone.__----_--____-----_-___-__--___________. 9 Blacksmith limestone._________________________________ 10 Bloomington formation..... _-_-_--___-____-_-_____-____ 11 Nounan limestone. _______-________ ____________________ 12 St. Charles limestone.. ---_------------------_--_-.-._ 13 Ordovician system._'_____________.___.__________________^__ -

USGS Jarbidge River Bull Trout Project

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Distribution and Movement of Bull Trout in the Upper Jarbidge River Watershed, Nevada Open-File Report 2010-1033 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Distribution and Movement of Bull Trout in the Upper Jarbidge River Watershed, Nevada By M. Brady Allen, Patrick J. Connolly, Matthew G. Mesa, Jodi Charrier, and Chris Dixon Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Open-File Report 2010–1033 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Allen, M.B., Connolly, P.J., Mesa, M.G., Charrier, Jodi, and Dixon, Chris, 2010, Distribution and movement of bull trout in the upper Jarbidge River watershed, Nevada: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2010-1033, 80 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

Lakes, Rivers & Hot Springs

LAKES, RIVERS & HOT SPRINGS Idaho has some of the most impressive water in the nation, and several of the state’s claims to fame are located in Southwest Idaho. Writers covering adventure, family and nature travel will find uncrowded, accessible lakes, rivers and hot springs in Southwest Idaho. RIVERS Multiple sections of the Payette River and Salmon River LAKES & RESERVOIRS are world-famous whitewater destinations. Watch the Southwest Idaho is a water recreation mecca. The area pros during the North Fork Championships or try for has dozens of reservoirs and lakes, including but not yourself with Cascade Raft & Kayak. limited to: Anderson Ranch, Arrowrock, C.J. Strike, Lake The mighty Snake River runs through Southwest Idaho, Cascade, Deadwood, Lucky Peak, Black Canyon and nourishing a massive agriculture and wine region. The river Payette Lake. turns north at the Oregon-Idaho border and runs through These bodies of water are the perfect place to take the Hells Canyon, the deepest river gorge in North America. boat out for the day. Spend an afternoon on Payette Lake Experience the impressive canyon on a whitewater on a McCall Lake Cruise. Go paddleboarding on clean, raft or jet boat tour with Hells Canyon Adventures or glacial water. Fish year-round in Southwest Idaho — Hells Canyon Raft. You’re sure to see wildlife in Hells it’s one of the only places this far inland where you can Canyon, including bald eagles, raptors, coyotes and bears. catch steelhead and salmon. The Owyhee River and Jarbidge River are perhaps two of the most remote, uncharted waters in the nation. -

Rmrs 2008 Rogers P001.Pdf

Forest Ecology and Management 256 (2008) 1760–1770 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Lichen community change in response to succession in aspen forests of the southern Rocky Mountains Paul C. Rogers a,*, Ronald J. Ryel b a Western Aspen Alliance, Utah State University, Department of Wildland Resources, 5200 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322, USA b Utah State University, Department of Wildland Resources, 5200 Old Main Hill, Room 108, Logan, UT 84322, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In western North America, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is the most common hardwood in Received 6 July 2007 montane landscapes. Fire suppression, grazing and wildlife management practices, and climate patterns Received in revised form 21 May 2008 of the past century are all potential threats to aspen coverage in this region. If aspen-dependent species Accepted 22 May 2008 are losing habitat, this raises concerns about their long-term viability. Though lichens have a rich history as air pollution indicators, we believe that they may also be useful as a metric of community diversity Keywords: associated with habitat change. We established 47 plots in the Bear River Range of northern Utah and Aspen southern Idaho to evaluate the effects of forest succession on epiphytic macrolichen communities. Plots Lichens Diversity were located in a narrow elevational belt (2134–2438 m) to minimize the known covariant effects of Community analysis elevation and moisture on lichen communities. Results show increasing total lichen diversity and a Succession decrease in aspen-dependent species as aspen forests succeed to conifer cover types. -

Structural and Lithological Influences on the Tony Grove Alpine Karst

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2016 Structural and Lithological Influences on the onyT Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah Kirsten Bahr Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Bahr, Kirsten, "Structural and Lithological Influences on the onyT Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah" (2016). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 5015. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/5015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRUCTURAL AND LITHOLOGICAL INFLUENCES ON THE TONY GROVE ALPINE KARST SYSTEM, BEAR RIVER RANGE, NORTH-CENTRAL UTAH by Kirsten Bahr A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology Approved: ______________________________ ______________________________ W. David Liddell, Ph.D. Robert Q. Oaks, Jr, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________________ ______________________________ Thomas E. Lachmar, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2016 ii Copyright © Kirsten Bahr 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Structural and Lithological Influences on the Tony Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah by Kirsten Bahr, Master of Science Utah State University, 2016 Major Professor: Dr. W. -

Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1969 Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho Philip L. VanDorston Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation VanDorston, Philip L., "Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho" (1969). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 3530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/3530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVffiONMENTAL ANALYSIS OF THE SWAN PEAK FORMATION IN THE BEAR RTVER RANGE , NORTH-CENTRAL UTAH AND SOUTHEASTERN IDAHO by Philip L. VanDorston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest appreciation is extended to Dr. Robert Q. Oaks, Jr. , for allowing me to develop the study along the directions I preferred, and for imposing few restrictions on the methodology, approach, and ensuing inter pretations. The assistance of Dr. J . Stewart Williams in identification of many of the fossils collected throughout the study was gratefully recetved. My appreciation is also extended to Dr. Raymond L. Kerns for assistance in obtaining the thin sections used in this study. -

December 2010 Storm Data Publication

DECEMBER 2010 VOLUME 52 NUMBER 12 STORM DATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: This cover represents a few weather conditions such as snow, hurricanes, tornadoes, heavy rain and flooding that may occur in any given location any month of the year. (Photo courtesy of NCDC.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month…....………………..........……..…………..…….……...….............4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena......…….…....…………...…...........….........................6 Reference Notes.............……...........................……….........…..….….............................................234 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: Joseph E. Kraft Assistant Editor: Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events resulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confirmed information on storms -

Evaluation of the Status of Bull Trout in the Jarbidge River Drainage, Idaho

EVALUATION OF THE STATUS OF BULL TROUT IN THE JARBIDGE RIVER DRAINAGE, IDAHO by Charles D. Warren and Fred E. Partridge Idaho Department of Fish and Game Region 4 Jerome, Idaho 83338 IDAHO BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 93-1 FEBRUARY 1 9 9 3 EVALUATION OF THE STATUS OF BULL TROUT IN THE JARBIDGE RIVER DRAINAGE, IDAHO Challenge Cost Share Project ID013-435206-25-9Z Charles D. Warren Regional Fishery Biologist and Fred E. Partridge Regional Fishery Manager Idaho Department of Fish and Game 1992 Prepared for the Boise District Bureau of Land Management ABSTRACT In an effort to gather information on bull trout Salvelinus confluentus on the Jarbidge River system within Idaho, habitat and fish communities were assessed at 19 sites on the river and its tributaries. Fish sampling was by either electrofishing or snorkel observations to assess population densities and age structures. Streambed composition, water column habitat, and stream width were evaluated for habitat. Fish sampling resulted in no bull trout, although a self sustaining population of wild redband/rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss spp, whitefish Prosopium williamsoni, four cyprinid, one cottid, and one catastomid species were found. Habitat and water temperature assessments indicate that bull trout may be limited by excessive water temperatures which were intensified by the recent drought conditions. Bull trout were last observed in Idaho by Department personnel in 1991 and one incidental observation was reported during 1992. Research in Nevada sampled bull trout in 1992. 1 INTRODUCTION The only native char in Idaho and Nevada is the bull trout Salvelinus confluentus.