Utah Forest Insect and Disease Conditions Report 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Biological Assessment

REVISED BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Effects of the Modified Idaho Roadless Rule on Federally Listed Threatened, Endangered, Candidate, and Proposed Species for Terrestrial Wildlife, Aquatics, and Plants September 12, 2008 FINAL BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Effects of the Modified Idaho Roadless Rule on Federally Listed Threatened, Endangered, Candidate, and Proposed Species for Terrestrial Wildlife, Aquatics, and Plants Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................... 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE FEDERAL ACTION .................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need..................................................................................................................................3 Description of the Project Area...............................................................................................................4 Modified Idaho Roadless Rule................................................................................................................6 Wild Land Recreation (WLR)...............................................................................................................6 Primitive (PRIM) and Special Areas of Historic and Tribal Significance (SAHTS)..............................7 Backcountry/ Restoration (Backcountry) (BCR)................................................................................10 General Forest, Rangeland, -

Macrolepidoptera Inventory of the Chilcotin District

Macrolepidoptera Inventory of the Chilcotin District Aud I. Fischer – Biologist Jon H. Shepard - Research Scientist and Crispin S. Guppy – Research Scientist January 31, 2000 2 Abstract This study was undertaken to learn more of the distribution, status and habitat requirements of B.C. macrolepidoptera (butterflies and the larger moths), the group of insects given the highest priority by the BC Environment Conservation Center. The study was conducted in the Chilcotin District near Williams Lake and Riske Creek in central B.C. The study area contains a wide variety of habitats, including rare habitat types that elsewhere occur only in the Lillooet-Lytton area of the Fraser Canyon and, in some cases, the Southern Interior. Specimens were collected with light traps and by aerial net. A total of 538 species of macrolepidoptera were identified during the two years of the project, which is 96% of the estimated total number of species in the study area. There were 29,689 specimens collected, and 9,988 records of the number of specimens of each species captured on each date at each sample site. A list of the species recorded from the Chilcotin is provided, with a summary of provincial and global distributions. The habitats, at site series level as TEM mapped, are provided for each sample. A subset of the data was provided to the Ministry of Forests (Research Section, Williams Lake) for use in a Flamulated Owl study. A voucher collection of 2,526 moth and butterfly specimens was deposited in the Royal BC Museum. There were 25 species that are rare in BC, with most known only from the Riske Creek area. -

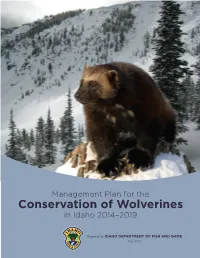

Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019

Management Plan for the Conservation of Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME July 2014 2 Idaho Department of Fish & Game Recommended Citation: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2014. Management plan for the conservation of wolverines in Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Idaho Department of Fish and Game – Wolverine Planning Team: Becky Abel – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Southeast Region Bryan Aber – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Upper Snake Region Scott Bergen PhD – Senior Wildlife Research Biologist, Statewide, Pocatello William Bosworth – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Rob Cavallaro – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Upper Snake Region Rita D Dixon PhD – State Wildlife Action Plan Coordinator, Headquarters Diane Evans Mack – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, McCall Subregion Sonya J Knetter – Wildlife Diversity Program GIS Analyst, Headquarters Zach Lockyer – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southeast Region Michael Lucid – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Panhandle Region Joel Sauder PhD – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Clearwater Region Ben Studer – Web and Digital Communications Lead, Headquarters Leona K Svancara PhD – Spatial Ecology Program Lead, Headquarters Beth Waterbury – Team Leader & Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Salmon Region Craig White PhD – Regional Wildlife Manager, Southwest Region Ross Winton – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Magic Valley Region Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at fishandgame.idaho.gov/wolverine-conservation-plan Front Cover Photo: Composite photo: Wolverine photo by AYImages; background photo of the Beaverhead Mountains, Lemhi County, Idaho by Rob Spence, Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Program, Wildlife conservation Society. Back Cover Photo: Release of Wolverine F4, a study animal from the Central Idaho Winter Recreation/Wolverine Project, from a live trap north of McCall, 2011. -

Forest Management Plan Yakama Reservation

Forest Management Plan Yakama Reservation United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Yakama Agency Branch of Forestry and the Yakama Nation Toppenish, Washington September 2005 Forest Management Plan Signature Page i Forest Management Plan Tribal Council Resolution T-021-04 September 2005 ii Forest Management Plan Tribal Council Resolution T-159-05 September 2005 iii Forest Management Plan General Council Resolution GC-02-06 September 2005 iv Forest Management Plan Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This Forest Management Plan (FMP) is the result of the cooperative efforts of many people over an extended period of time, incorporating the outstanding talents and knowledge of personnel from the Yakama Nation and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, including the Yakama Nation Department of Natural Resources, Yakama Nation Land Enterprise, Yakama Forest Products, Yakama Agency Branch of Forestry, and Yakama Agency Natural Resources Program. In addition, Yakama tribal members provided information and direction that was critical to the preparation of this Forest Management Plan. Achievement of their goals, desires, and visions for the future of the Yakama Forest was the basis for the development of the management directions in this document. The leadership and advice of the Yakama Tribal Council, General Council Officers, the Yakama Agency Forest Manager, and the Yakama Agency Superintendent were significant to the development of the FMP. Particularly noteworthy was the assistance and encouragement provided by the Chairman and members of the Tribal Council Timber, Grazing, Overall Economic Development Committee. September 2005 v Forest Management Plan Preface Preface This Forest Management Plan (FMP) for the Yakama Reservation was developed in coordination with the Yakama Nation to direct the management of the Yakama Nation’s forest and woodlands. -

Forest Insect Conditions in the United States 1966

FOREST INSECT CONDITIONS IN THE UNITED STATES 1966 FOREST SERVICE ' U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Foreword This report is the 18th annual account of the scope, severity, and trend of the more important forest insect infestations in the United States, and of the programs undertaken to check resulting damage and loss. It is compiled primarily for managers of public and private forest lands, but has become useful to students and others interested in outbreak trends and in the location and extent of pest populations. The report also makes possible n greater awareness of the insect prob lem and of losses to the timber resource. The opening section highlights the more important conditions Nationwide, and each section that pertains to a forest region is prefaced by its own brief summary. Under the Federal Forest Pest Control Act, a sharing by Federal and State Governments the costs of surveys and control is resulting in a stronger program of forest insect and disease detection and evaluation surveys on non-Federal lands. As more States avail themselves of this financial assistance from the Federal Government, damage and loss from forest insects will become less. The screening and testing of nonpersistent pesticides for use in suppressing forest defoliators continued in 1966. The carbamate insecticide Zectran in a pilot study of its effectiveness against the spruce budworm in Montana and Idaho appeared both successful and safe. More extensive 'tests are planned for 1967. Since only the smallest of the spray droplets reach the target, plans call for reducing the spray to a fine mist. The course of the fine spray, resulting from diffusion and atmospheric currents, will be tracked by lidar, a radar-laser combination. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0099135A1 Enan (43) Pub

US 20090099.135A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0099135A1 Enan (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 16, 2009 (54) PEST CONTROL COMPOSITIONS AND Publication Classification METHODS (51) Int. Cl. AOIN 57/6 (2006.01) AOIN 47/2 (2006.01) (75) Inventor: Essam Enan, Davis, CA (US) AOIN 43/12 (2006.01) AOIN 57/4 (2006.01) AOIN 53/06 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: AOIN 5L/00 (2006.01) SONNENSCHEN NATH & ROSENTHAL LLP AOIN 43/40 (2006.01) AOIP3/00 (2006.01) P.O. BOX 061080, WACKER DRIVE STATION, AOIP 7/04 (2006.01) SEARS TOWER AOIP 7/02 (2006.01) CHICAGO, IL 60606-1080 (US) AOIN 43/90 (2006.01) AOIN 43/6 (2006.01) AOIN 43/56 (2006.01) (73) Assignee: TyraTech, Inc., Melbourne, FL AOIN 29/2 (2006.01) (US) AOIN 43/52 (2006.01) AOIN 57/12 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ........... 514/86; 514/477; 514/469; 514/481; (21) Appl. No.: 12/009,220 514/395; 514/122:514/89: 514/486; 514/132: 514/748; 514/520; 514/531; 514/.407: 514/365; 514/341; 514/453: 514/343; 514/299 (22) Filed: Jan. 16, 2008 (57) ABSTRACT Embodiments of the present invention provide compositions for controlling a target pest including a pest control product Related U.S. Application Data and at least one active agent, wherein: the active agent can be capable of interacting with a receptor in the target pest; the (60) Provisional application No. 60/885,214, filed on Jan. pest control product can have a first activity against the target 16, 2007, provisional application No. -

Geology and Mineral Resources of the Randolph Quadrangle, Utah -Wyoming

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 923 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE RANDOLPH QUADRANGLE, UTAH -WYOMING BY G. B. RICHARDSON UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. O. ......... Price 55 cents HALL LIBRARY CONTENTS Pag* Abstract.____________--__-_-_-___-___-_---------------__----_____- 1 Introduction- ____________-__-___---__-_-_---_-_-----_----- -_______ 1 Topography. _____________________________________________________ 3 Bear River Range._.___---_-_---_-.---.---___-___-_-__________ 3 Bear River-Plateau___-_-----_-___-------_-_-____---___________ 5 Bear Lake-Valley..-_--_-._-_-__----__----_-_-__-_----____-____- 5 Bear River Valley.___---------_---____----_-_-__--_______'_____ 5 Crawford Mountains .________-_-___---____:.______-____________ 6 Descriptive geology.______-_____-___--__----- _-______--_-_-________ 6 Stratigraphy _ _________________________________________________ 7 Cambrian system.__________________________________________ 7 Brigham quartzite.____________________________________ 7 Langston limestone.___________________________________ 8 Ute limestone.__----_--____-----_-___-__--___________. 9 Blacksmith limestone._________________________________ 10 Bloomington formation..... _-_-_--___-____-_-_____-____ 11 Nounan limestone. _______-________ ____________________ 12 St. Charles limestone.. ---_------------------_--_-.-._ 13 Ordovician system._'_____________.___.__________________^__ -

Rmrs 2008 Rogers P001.Pdf

Forest Ecology and Management 256 (2008) 1760–1770 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Lichen community change in response to succession in aspen forests of the southern Rocky Mountains Paul C. Rogers a,*, Ronald J. Ryel b a Western Aspen Alliance, Utah State University, Department of Wildland Resources, 5200 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322, USA b Utah State University, Department of Wildland Resources, 5200 Old Main Hill, Room 108, Logan, UT 84322, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In western North America, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is the most common hardwood in Received 6 July 2007 montane landscapes. Fire suppression, grazing and wildlife management practices, and climate patterns Received in revised form 21 May 2008 of the past century are all potential threats to aspen coverage in this region. If aspen-dependent species Accepted 22 May 2008 are losing habitat, this raises concerns about their long-term viability. Though lichens have a rich history as air pollution indicators, we believe that they may also be useful as a metric of community diversity Keywords: associated with habitat change. We established 47 plots in the Bear River Range of northern Utah and Aspen southern Idaho to evaluate the effects of forest succession on epiphytic macrolichen communities. Plots Lichens Diversity were located in a narrow elevational belt (2134–2438 m) to minimize the known covariant effects of Community analysis elevation and moisture on lichen communities. Results show increasing total lichen diversity and a Succession decrease in aspen-dependent species as aspen forests succeed to conifer cover types. -

Structural and Lithological Influences on the Tony Grove Alpine Karst

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2016 Structural and Lithological Influences on the onyT Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah Kirsten Bahr Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Bahr, Kirsten, "Structural and Lithological Influences on the onyT Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah" (2016). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 5015. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/5015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRUCTURAL AND LITHOLOGICAL INFLUENCES ON THE TONY GROVE ALPINE KARST SYSTEM, BEAR RIVER RANGE, NORTH-CENTRAL UTAH by Kirsten Bahr A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology Approved: ______________________________ ______________________________ W. David Liddell, Ph.D. Robert Q. Oaks, Jr, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________________ ______________________________ Thomas E. Lachmar, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2016 ii Copyright © Kirsten Bahr 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Structural and Lithological Influences on the Tony Grove Alpine Karst System, Bear River Range, North-Central Utah by Kirsten Bahr, Master of Science Utah State University, 2016 Major Professor: Dr. W. -

Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1969 Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho Philip L. VanDorston Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation VanDorston, Philip L., "Environmental Analysis of the Swan Peak Formation in the Bear River Range, North-Central Utah and Southeastern Idaho" (1969). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 3530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/3530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENVffiONMENTAL ANALYSIS OF THE SWAN PEAK FORMATION IN THE BEAR RTVER RANGE , NORTH-CENTRAL UTAH AND SOUTHEASTERN IDAHO by Philip L. VanDorston A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest appreciation is extended to Dr. Robert Q. Oaks, Jr. , for allowing me to develop the study along the directions I preferred, and for imposing few restrictions on the methodology, approach, and ensuing inter pretations. The assistance of Dr. J . Stewart Williams in identification of many of the fossils collected throughout the study was gratefully recetved. My appreciation is also extended to Dr. Raymond L. Kerns for assistance in obtaining the thin sections used in this study. -

Logan Canyon

C A C H E V A L L E Y / B E A R L A K E Guide to the LOGAN CANYON NATIONAL SCENIC BYWAY 1 explorelogan.com C A C H E V A L L E Y / B E A R L A K E 31 SITES AND STOPS TABLE OF CONTENTS Site 1 Logan Ranger District 4 31 Site 2 Canyon Entrance 6 Site 3 Stokes Nature Center / River Trail 7 hether you travel by car, bicycle or on foot, a Site 4 Logan City Power Plant / Second Dam 8 Wjourney on the Logan Canyon National Scenic Site 5 Bridger Campground 9 Byway through the Wasatch-Cache National Forest Site 6 Spring Hollow / Third Dam 9 Site 7 Dewitt Picnic Area 10 offers an abundance of breathtaking natural beauty, Site 8 Wind Caves Trailhead 11 diverse recreational opportunities, and fascinating Site 9 Guinavah-Malibu 12 history. This journey can calm your heart, lift your Site 10 Card Picnic Area 13 Site 11 Chokecherry Picnic Area 13 spirit, and create wonderful memories. Located Site 12 Preston Valley Campground 14 approximately 90 miles north of Salt Lake City, this Site 13 Right Hand Fork / winding stretch of U.S. Hwy. 89 runs from the city of Lodge Campground 15 Site 14 Wood Camp / Jardine Juniper 16 Logan in beautiful Cache Valley to Garden City on Site 15 Logan Cave 17 the shores of the brilliant azure-blue waters of Bear Site 16 The Dugway 18 Lake. It passes through colorful fields of wildflowers, Site 17 Blind Hollow Trailhead 19 Site 18 Temple Fork / Old Ephraim’s Grave 19 between vertical limestone cliffs, and along rolling Site 19 Ricks Spring 21 streams brimming with trout.