The Sources for the Life of St. Francis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholastic Reactions to the Radical Eschatology of Joachim of Fiore

The Abbot and the Doctors: Scholastic Reactions to the Radical Eschatology of Joachim of Fiore Bernard McGinn Church History, Vol. 40, No. 1. (Mar., 1971), pp. 30-47. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0009-6407%28197103%2940%3A1%3C30%3ATAATDS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6 Church History is currently published by American Society of Church History. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/asch.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Dec 2 00:48:04 2007 The Abbot and the Doctors: Scholastic Reactions to the Radical Eschatology of Joachim of Fiore BERNARDMCGINN "Why are these fools awaiting the end of the world?" This remark, said to have been made by Pope Boniface VIII during the perusal of a Joachite treatise? typifies what must have been the reaction of many thirteenth century popes to the eschatological groups of the time. -

Prayer in the Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano

PRAYER IN THE LIFE OF SAINT FRANCIS BY THOMAS OF CELANO J.A. Wayne Hellmann Brother Thomas of Celano,1 upon the request of Pope Gregory IX,2 shortly after the 1228 canonization of Francis of Assisi, wrote The Life of St. Francis.3 In the opening lines, Thomas describes the begin- nings of Francis’s conversion. Thomas writes that Francis, secluded in a cave, prayed that “God guide his way.”4 In the closing lines at the end of The Life, Thomas accents the public prayer of the church in the person of pope. After the canonization Pope Gregory went to Francis’s tomb to pray: “by the lower steps he enters the sanc- tuary to offer prayers and sacrifices.”5 From beginning to end, through- out the text of The Life of St. Francis, the author, Brother Thomas, weaves Francis’s life together through an integrative theology of prayer. To shape his vision of Francis, Thomas, as a hagiographer, moves with multiple theological and literary currents, old and new. At the core of his vision, however, Thomas presents the life of a saint that developed from beginning to end in prayer. To do this, he employs 1 Brother Thomas of Celano was born into the noble family of the Conti dei Marsi sometime between the years of 1185–1190. Celano, the place of his birth, is a small city in the Abruzzi region southeast of Aquila. Thomas may have included himself a reference in number 56 of his text that “some literary men and nobles gladly joined” Francis after his return from Spain in 1215. -

Lectio Divina

Go Deep! Session 6 “Fiat voluntas tua…” Luke 18: 9 – 14 “He then addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else – "Two people went up to the temple area to pray; one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector. The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, 'O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity--greedy, dishonest, adulterous--or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income.' Luke 18: 9 – 14 But the tax collector stood off at a distance and would not even raise his eyes to heaven but beat his breast and prayed, 'O God, be merciful to me a sinner.' I tell you, the latter went home justified, not the former; for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” #2. Avoiding Self-Reliance “Our blessed father [Francis] would say: "Too much confidence makes one guard too little against the enemy. If the devil can get but one hair from a man, he will soon make it grow into a beam. Even if after many years he still has not made him fall whom he has tempted, he is not put out over the delay, as long as he catches him in the end. For this is his (the devil) business, and he is busy about nothing else by day or by night."” Thomas of Celano St. Alphonsus de Ligouri “To obtain perseverance in good, we must not trust in our resolutions and in the promises we have made to God; if we trust in our own strength, we are lost. -

Dante and the Franciscans: Poverty and the Papacy in the ‘Commedia’ Nick Havely Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521833051 - Dante and the Franciscans: Poverty and the Papacy in the ‘Commedia’ Nick Havely Index More information Index Acquasparta, Matteo of (Franciscan Minister Beatrice 82, 85;inPurgatorio 99, 101, 109–13, General andCardinal) 151–2 118; andthe ‘ 515’ 118–21, 122;inParadiso Ad conditorem (Bull, 1322), see John XXII 122, 123, 125, 128–9, 163, 169, 182, 183, 187 Aeneas 47, 60 beguines 25 Alfani, Gianni 17 beguins (of Provence) 28, 164, 165, 166, Angelic Pope 97 172–5 Angelo Clareno 28, 39, 41, 42, 75, 166 Benedict, St 123, 147, 160, 185 Angiolieri, Cecco 10–11, 12 Benvenuto da Imola (commentary on Aquinas, St Thomas: on avarice 46; definition Commmedia) 93, 103 of ‘poor in spirit’ 88;inParadiso 149–51 Berlinghieri, Bonaventura, see Pescia Arnoldus of Villanova 75 Bernard, St (of Clairvaux) 24–5, 32–3, 34; and Assisi 51, 86, 139; frescoes in Upper Church wilderness 25;inParadiso (cantos 32–3) 177 143 Bible: Genesis 156; Proverbs 15, 23;Songof Augustine, St 34, 46, 148; definition of ‘poor Songs 168;Isaiah168; Jeremiah 168; in spirit’ 88, 99, 108 Matthew 23, 54, 55, 57, 88, 101, 133, 138, 156, authority, of Boniface VIII 66–8; of Cardinals 157, 172; Mark 55, 127, 137, 138; Luke 23, 84;ofChurch158; of Dante as persona, 55, 58, 106, 127, 133, 136, 156, 157; John 55, writer andvernacular poet 3, 5, 54, 58, 71, 84;ActsofApostles55, 57, 137, 157; 2 109, 123, 176–80, 186–7;ofEmperor156–7; Corinthians 30; Revelation 42, 53, of evangelical poverty 3, 58, 124, 131, 155;of 79, 80, 103, 110, 113, 115, 122, 171, 172, Nicholas -

Bonaventure As Minister General Dominic V. Monti on 2 February

BONAVENTURE AS MINISTER GENERAL Dominic V. Monti On 2 February 1257, at a chapter of the Order of Friars Minor held in Rome, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio was unanimously elected its minister general. This was at the suggestion of his predecessor, John of Parma. Bonaven- ture would then not hand over the reins of government until June 1274, at a chapter held in conjunction with the Second Council of Lyons. In the interim, he had presided over five other general chapters, which had endorsed his leadership and renewed his mandate. His seventeen-year term of office was far longer than any of his predecessors or any of his successors for more than a century. It was not simply the sheer length of Bonaventure’s tenure, however, that made it significant: it was the fact that it occurred at a critical juncture in Franciscan history, as the Lesser Brothers were struggling to formulate a clear self-understanding of their role in church and society.1 As minister general, Bonaventure played a truly singular role in this process: his policies and writings did much to define an identity for his brotherhood that would stamp it decisively for generations.2 1 For a general introduction to and translation of Bonaventure’s writings as general minister, see Dominic V. Monti, Writings Concerning the Franciscan Order (Works of St Bonaventure) 5 (Saint Bonaventure: 1994), and Opuscoli Francescani, intro. Luigi Pel- legrini (Opere di San Bonaventura) 1 (Rome: 1993). Treatments in general histories of the Order include John Moorman, A History of The Franciscan Order: from its Origins to the Year 1517 (Oxford: 1968), 140–155; Grado Giovanni Merlo, In the Name of St Francis, trans. -

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis A Blessing for Brother Leo The Canticle of the Creatures The First Letter to the Faithful The Second Letter to the Faithful A Letter to the Rulers of the Peoples The Praises of God The Earlier Rule The Later Rule A Rule for Hermitages The Testament True and Perfect Joy Franciscan Sources The Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul The Mirror of Perfection, Smaller Version The Mirror of Perfection, Larger Version The Sacred Exchange between Saint Francis and Lady Poverty The Anonymous of Perugia The Legend of the Three Companions The Legend of Perugia The Assisi Compilation The Sermons of Bonaventure The Major Legend by Bonaventure The Minor Legend by Bonaventure The Deeds of Saint Francis and His Companions The Little Flowers of Saint Francis The Chronicle of Jordan of Giano Secondary Sources Aristotle. 1953. The works of Aristotle translated into English, Vol.11. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Armstrong, Edward A.1973. Saint Francis : nature mystic : the derivation and significance of the nature stories in the Franciscan legend. Berkeley: University of California Press. Armstrong, Regis J. 1998. At. Francis of Assisi: writings for a Gospel life. NY: Crossroad. Armstrong, R.,Hellmann, JAW., & Short W. 1999. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Saint. Vol.1. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R,. Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2000. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Founder. Vol.2. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R., Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2001. Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, The Prophet. -

The Sources for the Life of St. Francis

http://ofm.org.mt/noelmuscat THE SOURCES FOR THE LIFE OF ST. FRANCIS Lecture 2 THE MODERN STUDY OF THE SOURCES The modern approach to the study of Franciscan hagiography began with the Irish Franciscan Luke Wadding, who in 1623 published a critical edition of the Writings of St. Francis, Opusucla Sancti Patris Francisci Assisiensis, in Antwerp. In 1625 Wadding began the publication of the Annales Minorum, a chronological history of the Order of Friars Minor from the beginnings till the year 1540. Other chronicles of the Order had been published by Nicholas Glassberger in 1508, Mark of Lisbon in 1557, and Francesco Gonzaga in 1587, to mention the most important. In 1671 the Jesuit scholar Daniel Papenbroch discovered a manuscript in Perugia, containing a life of St. Francis by brother John of Perugia. The manuscript was published again in the Acta Sanctorum by another Jesuit, Cornelius Suyskens, in 1768, as part of the monumental work of the Bollandists. It became known as the Anonymous of Perugia. Suyskens had also discovered the First Life of St. Francis by Thomas of Celano. In 1803 Stefano Rinaldi discovered the manuscript containing the second portrait which Thomas of Celano gives of St. Francis in 1247, namely, The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul. The discovery of these biographies prompted the scholar Niccolo Papini to publish two volumes entitled La Storia di S. Francesco d’Assisi (1825-27). In 1856 Stanislao Melchiorri published a compilation of the documentation which was discovered in his book La Leggenda di San Francesco d’Ascesi scritta dalli suoi compagni. -

Video Collection

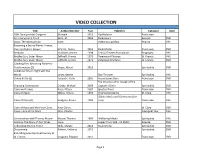

VIDEO COLLECTION Title Author/Director Year Publisher Category Kind 18th Quinquennial Congress Multiple 2012 Apollodorus Franciscan An Inconvenient Truth Gore, Al 2006 Paramount Science DVD Assisi: The Spiritual City none Videocity Casellaq History VHS Becoming a Sacred Flame: Francis, Clare and John's Gospel Schreck, Nancy 2011 Ruah Media Franciscan DVD Bernadin Doblmeir, Martin 1998 Family Theater Productions Biography VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1972 Paramount Pictures St. Francis VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1973 Paramount Pictures St. Francis DVD Catching Fire, Becoming Flame for Trasformation (2) Haase, Albert 2013 Spirituality DVD Celebrate What's Right with the World Jones, Dewitt Star Thrower Spirituality VHS Chiara di Dio (2) Tedeschi, Carlo 2005 Associazione Dare Franciscan DVD The Province of St. Joseph of the Choosing Compassion Crosby, Michael 2009 Capuchin Order Spirituality DVD Clare and Francis Bassi, Ettore 2007 Ignatius Press Franciscan DVD Clare of Assisi Sbicca, Arturo 1993 Oriente Occidente St. Clare VHS Oblate Media and Communication Clare of Assisi (2) Hodgson, Karen 1989 Corp. Franciscan VHS Clare of Assisi and the Poor Clares Poor Clares St. Clare DVD Closer Look at the Mass Faso, Charles Liturigical Year VHS Conversation with Thomas Moore Moore, Thomas 1995 Wellstring Media Spirituality VHS Cosmos: The Story of Our Times none copied from VHS - 12 DVD's Science DVD Cultivating Kindom Power Wills, Margie 2014 Ruah Media Spirituality DVD Discipleship Gittens, Anthony 2012 -

Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” Hope Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope Heaven: Where the Morning Lies November - December 2016 Faith makes us know God: we believe in Him with all our strength but we do not see Him. Our faith, therefore, needs to be supported by the certitude that some day we will see our God, that we will possess Him and willl be united to Him forever. The virtue of hope gives us this certitude by presenting God to us as our infinite good and our eternal reward. Fresco of the five prudent virgins, St. Godehard, Hildesheim, Germany Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Who has not heard of Pandora’s box? The Greek legend tells us that Pandora, the first woman created by Zeus, received many gifts—beauty, charm, wit, artistry, and lastly, curiosity. Included with the gifts was a box, which she was told never to open. But curiosity got the best of her. She lifted the lid, and out flew all the evils of the world, such as toil, illness, and despair. But at the bottom of the box lay Hope. Pandora’s last words were “Hope is what makes us strong. It is why we are here. It is what we fight with when all else is lost.” This story is the first thing which came to mind as I read over E Supremi, the first en- cyclical of our Patron Saint, St. Pius X. “In the midst of a progress in civilization which is justly extolled, who can avoid being appalled and afflicted when he beholds the greater part of mankind fighting among themselves so savagely as to make it seem as though strife were universal? The desire for peace is certainly harbored in every breast.” And the Pope goes on to explain that the peace of the godless is founded on sand. -

History Franciscan Movement 01 (Pdf)

HISTORY OF THE FRANCISCAN MOVEMENT Volume 1 FROM THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ORDER TO THE YEAR 1517 On-line course in Franciscan History at Washington Theological Union Washington DC By Noel Muscat OFM Jerusalem 2008 History of the Franciscan Movement. Volume 1: From the beginnings of the Order to the Year 1517 Course description and contents The Course aims at giving an overall picture of the history of the Franciscan Movement from the origins (1209) until Vatican Council II (1965). It deals primarily with the history of the Franciscan Order in two main sections, namely, from the foundation of the Order until the division into the Conventual and Observant families (1517), and from the Capuchin reform to modern times. Some lectures will also deal with the history of the Order of St. Clare, the Third Order Regular, and the Secular Franciscan Order. Chapter 1: The Franciscan Rule and Its Interpretation. • The form of life of the Gospel and the foundation of an Order (1209-1223). • The canonization of St. Francis and its aftermath (1226). • The generalate of Giovanni Parenti (1227-1232), the chapter of 1230, the question of the Rule and Testament of St. Francis, and the bulla Quo elongati. Chapter 2: Betrayal of the Founder‟s Intention? • The generalate of Elias (1232-1239). • The clericalization of the Order under Haymo of Faversham (1240-1244). • The Friars Minor and studies in the 13th century. Chapter 3: Further interpretation of the Rule and missionary expansion to the East. • The generalate of Crescentius of Iesi (1244-1247). The bulla Ordinem vestrum. • The first Franciscan missions in the Holy Land and Far East. -

Title Author Category

TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY A An Invitation to Joy - John Paul II Burke, Greg Popes Abbey Psalter, The - Trappist Monks Paulist Press Religious Orders An Outline of American Philosophy Bentley, John E. Philosophy ABC's of Angels, The Gates, Donna S. Teachings for Children An Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory Society of the IHOM Faith and Education ABC's of the Ten Commandments, The O'Connor, Francine M. Teachings for Children Anatomy of the Spirit Myss, Caroline, PhD Healing Abraham Feiler, Bruce Saints And The Angels Were Silent Lucado, Max Inspirational Accessory to Murder Terry, Randall A. Reference And We Shall Cast Rainbows Upon The Land Reitze, Raymond Spirituality Acropolis of Athens, The Al. N. Oekonomides Arts and Travel Angel Book, The Goldman, Karen Angels Acts Holman Reference Bible Reference Angel Letters Burnham, Sophy Angels Acts - A Devotional Commentary Zanchettin, Leo, Gen. Ed. Books of the Bible Angel Talk Crystal, Ruth Angels Acts of Kindness McCarty Faith and Education Angels Bussagli, Mario Angels Acts of the Apostles Barclay, William Books of the Bible Angels & Demons Kreeft, Peter Angels Acts of The Apostles Hamm, Dennis Books of the Bible Angels & Devils Cruse, Joan Carroll Angels Acts of the Apostles - Study Guide Little Rock Scripture Books of the Bible Angels and Miracles Am. Bible Society Angels Administration of Communion and Viaticum US Catholic Conference Reference Angels of God Aquilina, Mike Angels Advent and Christmas - St. Francis Assisi Kruse, John V., Compiled St. Francis of Assisi Angels of God Edmundite Missions Angels Advent and Christmas with Fr. Fulton Sheen Ed. Bauer, Judy Liturgical Seasons Anima Christi - Soul of Christ Mary Francis, Mother, PCC Jesus Advent Thirst … Christmas Hope Constance, Anita M., SC Liturgical Seasons Annulments and the Catholic Church Myers, Arhbishop John J., b.b. -

Unity Through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury Lake Forest College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lake Forest College Publications Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications All-College Writing Contest 5-1-2008 Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury Lake Forest College Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/allcollege_writing_contest Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Woodbury, Sara, "Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece" (2008). All-College Writing Contest. http://publications.lakeforest.edu/allcollege_writing_contest/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in All-College Writing Contest by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Saint Francis Altarpiece 1 Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury, Art 485 Image courtesy of the Web Gallery of Art (www.wga.hu) Saint Francis Altarpiece 2 The animal stories of Francis of Assisi are among the most recognizable images of the saint. Appearing on holy cards and garden statues, these animal narratives have come to represent a romantic, idealized relationship between humanity and nature.1 Francis’s animal stories, however, should not be regarded solely as sentimental, superfluous images. Rather, they should be recognized as a subject matter that has been adapted by artists, patrons, and cultural values to promote different agendas.