Thomas of Celano and the "Dies Irae" 43

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer in the Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano

PRAYER IN THE LIFE OF SAINT FRANCIS BY THOMAS OF CELANO J.A. Wayne Hellmann Brother Thomas of Celano,1 upon the request of Pope Gregory IX,2 shortly after the 1228 canonization of Francis of Assisi, wrote The Life of St. Francis.3 In the opening lines, Thomas describes the begin- nings of Francis’s conversion. Thomas writes that Francis, secluded in a cave, prayed that “God guide his way.”4 In the closing lines at the end of The Life, Thomas accents the public prayer of the church in the person of pope. After the canonization Pope Gregory went to Francis’s tomb to pray: “by the lower steps he enters the sanc- tuary to offer prayers and sacrifices.”5 From beginning to end, through- out the text of The Life of St. Francis, the author, Brother Thomas, weaves Francis’s life together through an integrative theology of prayer. To shape his vision of Francis, Thomas, as a hagiographer, moves with multiple theological and literary currents, old and new. At the core of his vision, however, Thomas presents the life of a saint that developed from beginning to end in prayer. To do this, he employs 1 Brother Thomas of Celano was born into the noble family of the Conti dei Marsi sometime between the years of 1185–1190. Celano, the place of his birth, is a small city in the Abruzzi region southeast of Aquila. Thomas may have included himself a reference in number 56 of his text that “some literary men and nobles gladly joined” Francis after his return from Spain in 1215. -

Lectio Divina

Go Deep! Session 6 “Fiat voluntas tua…” Luke 18: 9 – 14 “He then addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else – "Two people went up to the temple area to pray; one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector. The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, 'O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity--greedy, dishonest, adulterous--or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income.' Luke 18: 9 – 14 But the tax collector stood off at a distance and would not even raise his eyes to heaven but beat his breast and prayed, 'O God, be merciful to me a sinner.' I tell you, the latter went home justified, not the former; for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” #2. Avoiding Self-Reliance “Our blessed father [Francis] would say: "Too much confidence makes one guard too little against the enemy. If the devil can get but one hair from a man, he will soon make it grow into a beam. Even if after many years he still has not made him fall whom he has tempted, he is not put out over the delay, as long as he catches him in the end. For this is his (the devil) business, and he is busy about nothing else by day or by night."” Thomas of Celano St. Alphonsus de Ligouri “To obtain perseverance in good, we must not trust in our resolutions and in the promises we have made to God; if we trust in our own strength, we are lost. -

Low Requiem Mass

REQUIEM LOW MASS FOR TWO SERVERS The Requiem Mass is very ancient in its origin, being the predecessor of the current Roman Rite (i.e., the so- called “Tridentine Rite”) of Mass before the majority of the gallicanizations1 of the Mass were introduced. And so, many ancient features, in the form of omissions from the normal customs of Low Mass, are observed2. A. Interwoven into the beautiful and spiritually consoling Requiem Rite is the liturgical principle, that all blessings are reserved for the deceased soul(s) for whose repose the Mass is being celebrated. This principle is put into action through the omission of these blessings: 1. Holy water is not taken before processing into the Sanctuary. 2. The sign of the Cross is not made at the beginning of the Introit3. 3. C does not kiss the praeconium4 of the Gospel after reading it5. 4. During the Offertory, the water is not blessed before being mixed with the wine in the chalice6. 5. The Last Blessing is not given. B. All solita oscula that the servers usually perform are omitted, namely: . When giving and receiving the biretta. When presenting and receiving the cruets at the Offertory. C. Also absent from the Requiem Mass are all Gloria Patris, namely during the Introit and the Lavabo. D. The Preparatory Prayers are said in an abbreviated form: . The entire of Psalm 42 (Judica me) is omitted; consequently the prayers begin with the sign of the Cross and then “Adjutorium nostrum…” is immediately said. After this, the remainder of the Preparatory Prayers are said as usual. -

Dies Irae. Bernhard Pick 577

$1.00 per Year OCTOBER, 1911 Price, 10 Cents XLhc ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE Htevoteo to tbe Science of iReliaion, tbe IRelioion ot Science, ano tbe Extension ot tbe "Religious parliament 1oea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. ORIENTAL ART ADAPTED TO MODERN USES. (See page 609.) Woe ©pen Court publisbino Company CHICAGO LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d.). Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111. under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 191 1. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from CARLI: Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois http://www.archive.org/details/opencourt_oct1911caru $1.00 per Year OCTOBER, 1911 Price, 10 Cents XTbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE 2>evoteD to tbe Science of iRelfQion, tbe "Religion of Science, ano tbe Extension of tbe IReliQious parliament loea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. ORIENTAL ART ADAPTED TO MODERN USES. (See page 609.) Woe ©pen Court publishing Company CHICAGO LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d.). Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111. under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 191 1. VOL. XXV. (No. 10.) OCTOBER, 1911. NO. 665 CONTENTS PAGE Frontispiece. The Last Judgment by Michelangelo. Dies Irae. Bernhard Pick 577 The Text, 577 ; Authorship, 583 ; Contents, 584 ; General Acceptance, 587; A Parody, 591. -

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ziolkowski, Jan M. The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. Published Version https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/822 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40880864 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR AND PEACE, SEX AND VIOLENCE JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 6 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. -

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis A Blessing for Brother Leo The Canticle of the Creatures The First Letter to the Faithful The Second Letter to the Faithful A Letter to the Rulers of the Peoples The Praises of God The Earlier Rule The Later Rule A Rule for Hermitages The Testament True and Perfect Joy Franciscan Sources The Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul The Mirror of Perfection, Smaller Version The Mirror of Perfection, Larger Version The Sacred Exchange between Saint Francis and Lady Poverty The Anonymous of Perugia The Legend of the Three Companions The Legend of Perugia The Assisi Compilation The Sermons of Bonaventure The Major Legend by Bonaventure The Minor Legend by Bonaventure The Deeds of Saint Francis and His Companions The Little Flowers of Saint Francis The Chronicle of Jordan of Giano Secondary Sources Aristotle. 1953. The works of Aristotle translated into English, Vol.11. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Armstrong, Edward A.1973. Saint Francis : nature mystic : the derivation and significance of the nature stories in the Franciscan legend. Berkeley: University of California Press. Armstrong, Regis J. 1998. At. Francis of Assisi: writings for a Gospel life. NY: Crossroad. Armstrong, R.,Hellmann, JAW., & Short W. 1999. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Saint. Vol.1. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R,. Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2000. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Founder. Vol.2. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R., Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2001. Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, The Prophet. -

The Sources for the Life of St. Francis

http://ofm.org.mt/noelmuscat THE SOURCES FOR THE LIFE OF ST. FRANCIS Lecture 2 THE MODERN STUDY OF THE SOURCES The modern approach to the study of Franciscan hagiography began with the Irish Franciscan Luke Wadding, who in 1623 published a critical edition of the Writings of St. Francis, Opusucla Sancti Patris Francisci Assisiensis, in Antwerp. In 1625 Wadding began the publication of the Annales Minorum, a chronological history of the Order of Friars Minor from the beginnings till the year 1540. Other chronicles of the Order had been published by Nicholas Glassberger in 1508, Mark of Lisbon in 1557, and Francesco Gonzaga in 1587, to mention the most important. In 1671 the Jesuit scholar Daniel Papenbroch discovered a manuscript in Perugia, containing a life of St. Francis by brother John of Perugia. The manuscript was published again in the Acta Sanctorum by another Jesuit, Cornelius Suyskens, in 1768, as part of the monumental work of the Bollandists. It became known as the Anonymous of Perugia. Suyskens had also discovered the First Life of St. Francis by Thomas of Celano. In 1803 Stefano Rinaldi discovered the manuscript containing the second portrait which Thomas of Celano gives of St. Francis in 1247, namely, The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul. The discovery of these biographies prompted the scholar Niccolo Papini to publish two volumes entitled La Storia di S. Francesco d’Assisi (1825-27). In 1856 Stanislao Melchiorri published a compilation of the documentation which was discovered in his book La Leggenda di San Francesco d’Ascesi scritta dalli suoi compagni. -

Video Collection

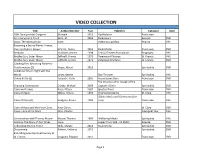

VIDEO COLLECTION Title Author/Director Year Publisher Category Kind 18th Quinquennial Congress Multiple 2012 Apollodorus Franciscan An Inconvenient Truth Gore, Al 2006 Paramount Science DVD Assisi: The Spiritual City none Videocity Casellaq History VHS Becoming a Sacred Flame: Francis, Clare and John's Gospel Schreck, Nancy 2011 Ruah Media Franciscan DVD Bernadin Doblmeir, Martin 1998 Family Theater Productions Biography VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1972 Paramount Pictures St. Francis VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1973 Paramount Pictures St. Francis DVD Catching Fire, Becoming Flame for Trasformation (2) Haase, Albert 2013 Spirituality DVD Celebrate What's Right with the World Jones, Dewitt Star Thrower Spirituality VHS Chiara di Dio (2) Tedeschi, Carlo 2005 Associazione Dare Franciscan DVD The Province of St. Joseph of the Choosing Compassion Crosby, Michael 2009 Capuchin Order Spirituality DVD Clare and Francis Bassi, Ettore 2007 Ignatius Press Franciscan DVD Clare of Assisi Sbicca, Arturo 1993 Oriente Occidente St. Clare VHS Oblate Media and Communication Clare of Assisi (2) Hodgson, Karen 1989 Corp. Franciscan VHS Clare of Assisi and the Poor Clares Poor Clares St. Clare DVD Closer Look at the Mass Faso, Charles Liturigical Year VHS Conversation with Thomas Moore Moore, Thomas 1995 Wellstring Media Spirituality VHS Cosmos: The Story of Our Times none copied from VHS - 12 DVD's Science DVD Cultivating Kindom Power Wills, Margie 2014 Ruah Media Spirituality DVD Discipleship Gittens, Anthony 2012 -

Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” Hope Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope Heaven: Where the Morning Lies November - December 2016 Faith makes us know God: we believe in Him with all our strength but we do not see Him. Our faith, therefore, needs to be supported by the certitude that some day we will see our God, that we will possess Him and willl be united to Him forever. The virtue of hope gives us this certitude by presenting God to us as our infinite good and our eternal reward. Fresco of the five prudent virgins, St. Godehard, Hildesheim, Germany Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Who has not heard of Pandora’s box? The Greek legend tells us that Pandora, the first woman created by Zeus, received many gifts—beauty, charm, wit, artistry, and lastly, curiosity. Included with the gifts was a box, which she was told never to open. But curiosity got the best of her. She lifted the lid, and out flew all the evils of the world, such as toil, illness, and despair. But at the bottom of the box lay Hope. Pandora’s last words were “Hope is what makes us strong. It is why we are here. It is what we fight with when all else is lost.” This story is the first thing which came to mind as I read over E Supremi, the first en- cyclical of our Patron Saint, St. Pius X. “In the midst of a progress in civilization which is justly extolled, who can avoid being appalled and afflicted when he beholds the greater part of mankind fighting among themselves so savagely as to make it seem as though strife were universal? The desire for peace is certainly harbored in every breast.” And the Pope goes on to explain that the peace of the godless is founded on sand. -

A Guide to Verdi's Requiem

A Guide to Verdi’s Requiem Created by Dr. Mary Jane Ayers You may have heard that over the last 29 years, texts of the mass. The purpose of the requiem the Sarasota Opera produced ALL of the mass is to ask God to give rest to the souls of operatic works of composer Guiseppi Verdi, the dead. The title “requiem” comes from the including some extremely famous ones, Aida, first word of the Latin phrase, Requiem Otello, and Falstaff. But Verdi, an amazing aeternam dona eis, Domine, (pronounced: reh- opera composer, is also responsible for the qui-em ay-tare-nahm doh-nah ay-ees, daw- creation of one of the most often performed mee-nay) which translates, Rest eternal grant religious works ever written, the Verdi them, Lord. Requiem. Like many of his operas, Verdi’s Requiem is written for a massive group of performers, including a double chorus, large orchestra, and four soloists: a soprano, a mezzo-soprano (a medium high female voice), a tenor, and a bass. Gregorian chant version of the beginning of a The solos written for the Requiem require Requiem, composed 10th century singers with rich, full, ‘operatic’ voices. So what is a requiem, and why would Verdi So why did Verdi decide to write a requiem choose to compose one? mass? In 1869, Verdi lost his friend, the great composer Giacomo Rossini. Verdi worked with other composers to cobble together a requiem with each composer writing a different section of the mass, but that did not work out. Four years later another friend died, and Verdi decided to keep what he had already composed and complete the rest of the entire requiem. -

Title Author Category

TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY A An Invitation to Joy - John Paul II Burke, Greg Popes Abbey Psalter, The - Trappist Monks Paulist Press Religious Orders An Outline of American Philosophy Bentley, John E. Philosophy ABC's of Angels, The Gates, Donna S. Teachings for Children An Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory Society of the IHOM Faith and Education ABC's of the Ten Commandments, The O'Connor, Francine M. Teachings for Children Anatomy of the Spirit Myss, Caroline, PhD Healing Abraham Feiler, Bruce Saints And The Angels Were Silent Lucado, Max Inspirational Accessory to Murder Terry, Randall A. Reference And We Shall Cast Rainbows Upon The Land Reitze, Raymond Spirituality Acropolis of Athens, The Al. N. Oekonomides Arts and Travel Angel Book, The Goldman, Karen Angels Acts Holman Reference Bible Reference Angel Letters Burnham, Sophy Angels Acts - A Devotional Commentary Zanchettin, Leo, Gen. Ed. Books of the Bible Angel Talk Crystal, Ruth Angels Acts of Kindness McCarty Faith and Education Angels Bussagli, Mario Angels Acts of the Apostles Barclay, William Books of the Bible Angels & Demons Kreeft, Peter Angels Acts of The Apostles Hamm, Dennis Books of the Bible Angels & Devils Cruse, Joan Carroll Angels Acts of the Apostles - Study Guide Little Rock Scripture Books of the Bible Angels and Miracles Am. Bible Society Angels Administration of Communion and Viaticum US Catholic Conference Reference Angels of God Aquilina, Mike Angels Advent and Christmas - St. Francis Assisi Kruse, John V., Compiled St. Francis of Assisi Angels of God Edmundite Missions Angels Advent and Christmas with Fr. Fulton Sheen Ed. Bauer, Judy Liturgical Seasons Anima Christi - Soul of Christ Mary Francis, Mother, PCC Jesus Advent Thirst … Christmas Hope Constance, Anita M., SC Liturgical Seasons Annulments and the Catholic Church Myers, Arhbishop John J., b.b. -

Pdf • an American Requiem

An American Requiem Our nation’s first cathedral in Baltimore An American Expression of our Roman Rite A Funeral Guide for helping Catholic pastors, choirmasters and families in America honor our beloved dead An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, And let perpetual light shine upon them. And may the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, Rest in Peace. Amen. Grave of Father Thomas Merton at Gethsemane, Kentucky "This is what I think about the Latin and the chant: they are masterpieces, which offer us an irreplaceable monastic and Christian experience. They have a force, an energy, a depth without equal … As you know, I have many friends in the world who are artists, poets, authors, editors, etc. Now they are well able to appre- ciate our chant and even our Latin. But they are all, without exception, scandalized and grieved when I tell them that probably this Office, this Mass will no longer be here in ten years. And that is the worst. The monks cannot understand this treasure they possess, and they throw it out to look for something else, when seculars, who for the most part are not even Christians, are able to love this incomparable art." — Thomas Merton wrote this in a letter to Dom Ignace Gillet, who was the Abbot General of the Cistercians of the Strict Observance (1964) An American Requiem: AN American expression of our Roman Rite Requiescat in Pace Praying for the Dead The Carrols were among the early founders of Maryland, but as Catholic subjects to the Eng- lish Crown they were unable to participate in the political life of the colony.