The Sources for the Life of St. Francis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer in the Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano

PRAYER IN THE LIFE OF SAINT FRANCIS BY THOMAS OF CELANO J.A. Wayne Hellmann Brother Thomas of Celano,1 upon the request of Pope Gregory IX,2 shortly after the 1228 canonization of Francis of Assisi, wrote The Life of St. Francis.3 In the opening lines, Thomas describes the begin- nings of Francis’s conversion. Thomas writes that Francis, secluded in a cave, prayed that “God guide his way.”4 In the closing lines at the end of The Life, Thomas accents the public prayer of the church in the person of pope. After the canonization Pope Gregory went to Francis’s tomb to pray: “by the lower steps he enters the sanc- tuary to offer prayers and sacrifices.”5 From beginning to end, through- out the text of The Life of St. Francis, the author, Brother Thomas, weaves Francis’s life together through an integrative theology of prayer. To shape his vision of Francis, Thomas, as a hagiographer, moves with multiple theological and literary currents, old and new. At the core of his vision, however, Thomas presents the life of a saint that developed from beginning to end in prayer. To do this, he employs 1 Brother Thomas of Celano was born into the noble family of the Conti dei Marsi sometime between the years of 1185–1190. Celano, the place of his birth, is a small city in the Abruzzi region southeast of Aquila. Thomas may have included himself a reference in number 56 of his text that “some literary men and nobles gladly joined” Francis after his return from Spain in 1215. -

Lectio Divina

Go Deep! Session 6 “Fiat voluntas tua…” Luke 18: 9 – 14 “He then addressed this parable to those who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else – "Two people went up to the temple area to pray; one was a Pharisee and the other was a tax collector. The Pharisee took up his position and spoke this prayer to himself, 'O God, I thank you that I am not like the rest of humanity--greedy, dishonest, adulterous--or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week, and I pay tithes on my whole income.' Luke 18: 9 – 14 But the tax collector stood off at a distance and would not even raise his eyes to heaven but beat his breast and prayed, 'O God, be merciful to me a sinner.' I tell you, the latter went home justified, not the former; for everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” #2. Avoiding Self-Reliance “Our blessed father [Francis] would say: "Too much confidence makes one guard too little against the enemy. If the devil can get but one hair from a man, he will soon make it grow into a beam. Even if after many years he still has not made him fall whom he has tempted, he is not put out over the delay, as long as he catches him in the end. For this is his (the devil) business, and he is busy about nothing else by day or by night."” Thomas of Celano St. Alphonsus de Ligouri “To obtain perseverance in good, we must not trust in our resolutions and in the promises we have made to God; if we trust in our own strength, we are lost. -

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis A Blessing for Brother Leo The Canticle of the Creatures The First Letter to the Faithful The Second Letter to the Faithful A Letter to the Rulers of the Peoples The Praises of God The Earlier Rule The Later Rule A Rule for Hermitages The Testament True and Perfect Joy Franciscan Sources The Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul The Mirror of Perfection, Smaller Version The Mirror of Perfection, Larger Version The Sacred Exchange between Saint Francis and Lady Poverty The Anonymous of Perugia The Legend of the Three Companions The Legend of Perugia The Assisi Compilation The Sermons of Bonaventure The Major Legend by Bonaventure The Minor Legend by Bonaventure The Deeds of Saint Francis and His Companions The Little Flowers of Saint Francis The Chronicle of Jordan of Giano Secondary Sources Aristotle. 1953. The works of Aristotle translated into English, Vol.11. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Armstrong, Edward A.1973. Saint Francis : nature mystic : the derivation and significance of the nature stories in the Franciscan legend. Berkeley: University of California Press. Armstrong, Regis J. 1998. At. Francis of Assisi: writings for a Gospel life. NY: Crossroad. Armstrong, R.,Hellmann, JAW., & Short W. 1999. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Saint. Vol.1. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R,. Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2000. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Founder. Vol.2. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R., Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2001. Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, The Prophet. -

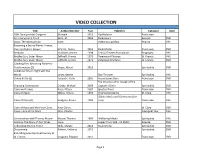

Video Collection

VIDEO COLLECTION Title Author/Director Year Publisher Category Kind 18th Quinquennial Congress Multiple 2012 Apollodorus Franciscan An Inconvenient Truth Gore, Al 2006 Paramount Science DVD Assisi: The Spiritual City none Videocity Casellaq History VHS Becoming a Sacred Flame: Francis, Clare and John's Gospel Schreck, Nancy 2011 Ruah Media Franciscan DVD Bernadin Doblmeir, Martin 1998 Family Theater Productions Biography VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1972 Paramount Pictures St. Francis VHS Brother Sun, Sister Moon Zeffirelli, Franco 1973 Paramount Pictures St. Francis DVD Catching Fire, Becoming Flame for Trasformation (2) Haase, Albert 2013 Spirituality DVD Celebrate What's Right with the World Jones, Dewitt Star Thrower Spirituality VHS Chiara di Dio (2) Tedeschi, Carlo 2005 Associazione Dare Franciscan DVD The Province of St. Joseph of the Choosing Compassion Crosby, Michael 2009 Capuchin Order Spirituality DVD Clare and Francis Bassi, Ettore 2007 Ignatius Press Franciscan DVD Clare of Assisi Sbicca, Arturo 1993 Oriente Occidente St. Clare VHS Oblate Media and Communication Clare of Assisi (2) Hodgson, Karen 1989 Corp. Franciscan VHS Clare of Assisi and the Poor Clares Poor Clares St. Clare DVD Closer Look at the Mass Faso, Charles Liturigical Year VHS Conversation with Thomas Moore Moore, Thomas 1995 Wellstring Media Spirituality VHS Cosmos: The Story of Our Times none copied from VHS - 12 DVD's Science DVD Cultivating Kindom Power Wills, Margie 2014 Ruah Media Spirituality DVD Discipleship Gittens, Anthony 2012 -

Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” Hope Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope Heaven: Where the Morning Lies November - December 2016 Faith makes us know God: we believe in Him with all our strength but we do not see Him. Our faith, therefore, needs to be supported by the certitude that some day we will see our God, that we will possess Him and willl be united to Him forever. The virtue of hope gives us this certitude by presenting God to us as our infinite good and our eternal reward. Fresco of the five prudent virgins, St. Godehard, Hildesheim, Germany Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Who has not heard of Pandora’s box? The Greek legend tells us that Pandora, the first woman created by Zeus, received many gifts—beauty, charm, wit, artistry, and lastly, curiosity. Included with the gifts was a box, which she was told never to open. But curiosity got the best of her. She lifted the lid, and out flew all the evils of the world, such as toil, illness, and despair. But at the bottom of the box lay Hope. Pandora’s last words were “Hope is what makes us strong. It is why we are here. It is what we fight with when all else is lost.” This story is the first thing which came to mind as I read over E Supremi, the first en- cyclical of our Patron Saint, St. Pius X. “In the midst of a progress in civilization which is justly extolled, who can avoid being appalled and afflicted when he beholds the greater part of mankind fighting among themselves so savagely as to make it seem as though strife were universal? The desire for peace is certainly harbored in every breast.” And the Pope goes on to explain that the peace of the godless is founded on sand. -

Title Author Category

TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY TITLE AUTHOR CATEGORY A An Invitation to Joy - John Paul II Burke, Greg Popes Abbey Psalter, The - Trappist Monks Paulist Press Religious Orders An Outline of American Philosophy Bentley, John E. Philosophy ABC's of Angels, The Gates, Donna S. Teachings for Children An Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory Society of the IHOM Faith and Education ABC's of the Ten Commandments, The O'Connor, Francine M. Teachings for Children Anatomy of the Spirit Myss, Caroline, PhD Healing Abraham Feiler, Bruce Saints And The Angels Were Silent Lucado, Max Inspirational Accessory to Murder Terry, Randall A. Reference And We Shall Cast Rainbows Upon The Land Reitze, Raymond Spirituality Acropolis of Athens, The Al. N. Oekonomides Arts and Travel Angel Book, The Goldman, Karen Angels Acts Holman Reference Bible Reference Angel Letters Burnham, Sophy Angels Acts - A Devotional Commentary Zanchettin, Leo, Gen. Ed. Books of the Bible Angel Talk Crystal, Ruth Angels Acts of Kindness McCarty Faith and Education Angels Bussagli, Mario Angels Acts of the Apostles Barclay, William Books of the Bible Angels & Demons Kreeft, Peter Angels Acts of The Apostles Hamm, Dennis Books of the Bible Angels & Devils Cruse, Joan Carroll Angels Acts of the Apostles - Study Guide Little Rock Scripture Books of the Bible Angels and Miracles Am. Bible Society Angels Administration of Communion and Viaticum US Catholic Conference Reference Angels of God Aquilina, Mike Angels Advent and Christmas - St. Francis Assisi Kruse, John V., Compiled St. Francis of Assisi Angels of God Edmundite Missions Angels Advent and Christmas with Fr. Fulton Sheen Ed. Bauer, Judy Liturgical Seasons Anima Christi - Soul of Christ Mary Francis, Mother, PCC Jesus Advent Thirst … Christmas Hope Constance, Anita M., SC Liturgical Seasons Annulments and the Catholic Church Myers, Arhbishop John J., b.b. -

Unity Through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury Lake Forest College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lake Forest College Publications Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications All-College Writing Contest 5-1-2008 Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury Lake Forest College Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/allcollege_writing_contest Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Woodbury, Sara, "Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece" (2008). All-College Writing Contest. http://publications.lakeforest.edu/allcollege_writing_contest/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in All-College Writing Contest by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Saint Francis Altarpiece 1 Unity through Francis: Demonstrations of Franciscan Authority in the Animal Stories of the Saint Francis Altarpiece Sara Woodbury, Art 485 Image courtesy of the Web Gallery of Art (www.wga.hu) Saint Francis Altarpiece 2 The animal stories of Francis of Assisi are among the most recognizable images of the saint. Appearing on holy cards and garden statues, these animal narratives have come to represent a romantic, idealized relationship between humanity and nature.1 Francis’s animal stories, however, should not be regarded solely as sentimental, superfluous images. Rather, they should be recognized as a subject matter that has been adapted by artists, patrons, and cultural values to promote different agendas. -

St. Francis of Assisi, the Writings of Saint Francis of Assisi (12Thc)

St. Francis of Assisi_0535 http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/EBook.php?recordID=0535 THE ONLINE LIBRARY OF LIBERTY © Liberty Fund, Inc. 2005 http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/index.php ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI, THE WRITINGS OF SAINT FRANCIS OF ASSISI (12THC) URL of this E-Book: http://oll.libertyfund.org/EBooks/St. Francis of Assisi_0535.pdf URL of original HTML file: http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/HTML.php?recordID=0535 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Saint Francis of Assisi founded the Franciscan order and was an important participant in the religious revival of the late Middle Ages. ABOUT THE BOOK A collection of St Francis’s writings, including various rules, letters, and prayers. THE EDITION USED The Writings of Saint Francis of Assisi, newly translated into English with an Introduction and Notes by Father Paschal Robinson (Philadelphia: The Dolphin Press, 1906). COPYRIGHT INFORMATION The text of this edition is in the public domain. FAIR USE STATEMENT This material is put online to further 1 of 160 9/13/05 11:55 AM St. Francis of Assisi_0535 http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/EBook.php?recordID=0535 the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit. _______________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. Printed Editions Wadding’s Edition. First Critical Edition Endnotes PART I ADMONITIONS, RULES, ETC I. Words of Admonition of our Holy Father St. Francis. ADMONITIONS. 1. Of the Lord’s Body. 2. The Evil of Self-will. -

182-8 Catholic Spirit Txt.Indd

Contents Preface ix General Introduction: How to Use this Sourcebook 1 Unit 1: What We Believe (Th e Profession of Faith) 9 Creation and Nature of God “God’s Grandeur”: Gerard Manley Hopkins 14 “Th e Teacher of Wisdom”: Oscar Wilde 17 “Pigeon Feathers”: John Updike 24 “Th e Creation”: James Weldon Johnson and 52 “Th e Burning Babe”: Robert Southwell “Parker’s Back”: Flannery O’Connor 59 Th e Journey of the Mind into God: St. Bonaventure 84 Seeing with the Artist 89 “Questions for Fra Angelico”: Annabelle Mosley 92 Looking at Film 93 God’s Ongoing Revelation “Th e Bethlehem Explosion”: Madeleine L’Engle 96 “Where Love Is, God Is”: Leo Tolstoy 100 “A Woman of Little Faith” from Th e Brothers Karamazov: 115 Fyodor Dostoyevsky Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina of Tuscany: 121 Galileo Galilei and “Address to the Pontifi cal Academy of Science”: Pope John Paul II Seeing with the Artist 137 Looking at Film 137 Listening to Sacred Music 138 Th e Uniqueness of Mary, the Mother of God “Th e Blessed Virgin Mary Compared to a Window”: 141 Th omas Merton “Our Lady’s Juggler”: Anatole France 145 Th e Communion of Saints “Marble Floor”: Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II) 153 An Account of the Martyrdom of St. Blandine and 156 Her Companions in AD 177, from Th e Ecclesiastical History: Eusebius of Caesarea Life Everlasting Two Letters of St. Th érèse of Lisieux to Abbe Belliere: 165 St. Th érèse of Lisieux Seeing with the Artist 173 Looking at Film 175 Unit 2: How We Touch God and How God Touches Us 179 (Th e Celebration of the Christian Mystery) Sacred Times and Sacred Spaces “St. -

The Complete Francis of Assisi Paraclete Giants

THE COMPLETE FRANCIS OF ASSISI PARACLETE GIANTS About This Series: Each Paraclete Giant presents collected works of one of Christianity’s great- est writers—“giants” of the faith. These essential volumes share the pivotal teachings of leading Christian figures throughout history with today’s theological students and all people seeking spiritual wisdom. The Complete Paraclete Giant Series… THE COMPLETE CLOUD OF UNKNOWING THE COMPLETE FÉNELON THE COMPLETE IMITATION OF CHRIST THE COMPLETE INTRODUCTION TO THE DEVOUT LIFE His Life, The Complete Writings, and THE COMPLETE JULIAN OF NORWICH The Little Flowers THE COMPLETE THÉRÈSE OF LISIEUX THE COMPLETE MADAME GUYON THE COMPLETE FRANCIS OF ASSISI For more information, visit www.paracletepress.com. PARACLETE GIANTS The C OMPLETE of His Life, The Completessisi Writings, and The Little Flowers Edited, Translated, and Introduced by Jon M. Sweeney Paraclete Press BREWSTER, MASSACHUSETTS 2015 First printing The Complete Francis of Assisi: His Life, The Complete Writings, and The Little Flowers Copyright © 2015 by Jon M. Sweeney ISBN 978-1-61261-688-9 Unless otherwise noted, all scriptural references used by the editor are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NAB) are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. -

Thomas of Celano and the "Dies Irae" 43

Thomas of Celano and the "D ies Irae Donald E. Demaray Thomas of Celano� "Friar Minor, poet, and hagiographical ^ writer. was probably born at Celano in the Province of Abruzzi, about 1200. It is thought that he died about 1255, though neither the date of his birth nor death is absolutely known to scholars of medi eval history. A Franciscan friar, he was the devout biographer and disciple of St. Francis of Assisi. In regard to the latter he was one of the first group (comprising eleven) of disciples who followed St. Francis. Thomas joined this group in 1214, and traveled in Germany spreading the good news of a redeeming Christ, Upon one occasion it is thought that he went into Germany with Caesar of Speyer. The following year he was made custos of the convents at Mayence, Worms, Speyer, and Cologne. Later, Caesar of Speyer, on his return to Italy, made him vicar in the government of the German province. Then, Thomas was an early biographer of St. Francis. Some say he was the first biographer, while others say he was only an early writer on the life of St. Francis. He was commissioned by Gregory IX to write Francis' life. In 1229 he completed the First Legend, while in 1247, at the command of the minister general, he wrote the Second Legend. There was yet a third volume entitled the Tract on the Miracles of St. Francis. The latter was published a few years after the Second Legend, at the encouragement of the Blessed John of Parma. Henry Osborn Taylor has characterized the Franciscan monk as follows: One of the earliest biographers of St. -

FINDING JOY in SINGING with the ANGELS the GRACE of JUBILATION the ASTOUNDING PRAYER THAT CAME with PENTECOST by Deacon Eddie Ensley

Providing Support and Leadership SCRC for the Catholic Charismatic Renewal SPIRIT Volume 48 Southern California Renewal Communities Number 3 May / June 2020 FINDING JOY IN SINGING WITH THE ANGELS THE GRACE OF JUBILATION THE ASTOUNDING PRAYER THAT CAME WITH PENTECOST by Deacon Eddie Ensley One of the happiest words.”[i] Komonchak quotes from As part of my discovery discoveries in my life has been Augustine’s Commentary on the of the Catholic Church, I read the an ancient form of prayer that Psalms: [i] early Church Fathers and Mothers offers a foretaste of heaven, a What I am about to say you and the original lives of the way of opening up so God can fill already know. One who is whooping saints, especially St. Francis. The us with boundless joy. Great description of thousands of theologians like St. Thomas people praying in jubilation Aquinas and St. Augustine and the genuinely felt prayed this way. Great spiritual emotion in their worship was leaders like St. Francis prayed far richer than what I had seen this way. Countless numbers at modern day charismatic of Christians prayed this way Masses and prayer groups. in the first sixteen centuries When people prayed this of the history of the Church. way miracles and healing After years this prayer form is broke out. experiencing a resurgence of There are hundreds interest through the charismatic of references to jubilation renewal movement. through the centuries. It is a way of prayer Augustine describes a Mass found in the Catholic tradition he celebrated in his home called “jubilation” (jubilatio church in Hippo when two in Latin), which modern-day people were healed of palsy: charismatics called “singing “The exultation continued, in tongues.” In an article on and the wordless praise to jubilation in Commonweal, God was shouted so loud Joseph A.