• • • • • • 3 News 13 BFS Convention 27 John Radcliff and the Antipodes 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

Pan-March-2020.Pdf

PANJOURNAL OF THE BRITISH FLUTE SOCIETY MARCH 2020 “This is my Flute. There are many like it, but this one is mine” Juliette Hurel Maesta 18K - Forte Headjoint pearlflutes.eu Principal Flautist of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra contents The British Flute Society news & events 24 President 2 BFS NEWS William Bennett OBE 4 NOTES FROM THE CHAIR 6 NEWS Vice President 11 FLUTE CHOIR NEWS Wissam Boustany 13 TRADE NEWS 14 EVENTS LISTINGS Honorary Patrons 16 INTERNATIONAL EVENTS Sir James Galway 23 FLUTE CHOIR FOCUS: and Lady Jeanne Galway WOKING FLUTE CHOIR 32 Conductorless democracy in action. Vice Presidents Emeritus Atarah Ben-Tovim MBE features Sheena Gordon 24 ALEXANDER MURRAY: I’VE GONE ON LEARNING THE FLUTE ALL MY LIFE Secretary Cressida Godfrey examines an astonishing Rachel Shirley career seven decades long and counting. [email protected] 32 CASE FOR MOVEMENT EDUCATION Musicians move for a living. Kelly Mollnow 39 Membership Secretary Wilson shows them how to do it freely and [email protected] efficiently through Body Mapping. 39 WILLIAM BENNETT’S The British Flute Society is a HAPPY FLUTE FESTIVAL Charitable Incorporated Organisation Edward Blakeman describes some of the registered charity number 1178279 enticing treats on offer this summer in Wibb’s feel-good festival. Pan 40 GRADED EXAMS AND BEYOND: The Journal of the EXPLORING THE OPTIONS AVAILABLE 40 British Flute Society The range of exams can be daunting for Volume 39 Number 1 student and teacher alike. David Barton March 2020 gives a comprehensive review. 42 STEPHEN WESSEL: Editor A NATIONAL TREASURE Carla Rees Judith Hall gives a personal appreciation of [email protected] the flutemaker in the year of his retirement. -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild Alice Bennett © 2012 Statement of Responsibility: This document does not contain any material, which has been accepted for the award of any other degree from any university. To the best of my knowledge, this document does not contain any material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference is given. Candidate: Alice Bennett Supervisor: Dr. Joel Crotty Signed:____________________ Date:____________________ 2 Contents Statement of Responsibility: ................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter Outlines ............................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter Two ......................................................................................................................................... -

21St Century Consort Composer Performance List

21st Century Consort Composer List 1975 - 2016 Archive of performance recordings Hans Abrahamsen Winternacht (1976-78) 1986-12-06 (15:27) flute, clarinet, trumpet, French horn, piano, violin, cello, conductor John Adams Road Movies 2012-05-05 (15:59) violin, piano Hallelujah Junction 2016-02-06 (17:25) piano, piano Shaker Loops (1978) 2000-04-15 (26:34) violin, violin, violin, viola, cello, cello, contrabass, conductor Bruce Adolphe Machaut is My Beginning (1989) 1996-03-16 (5:01) violin, cello, flute, clarinet, piano Miguel Del Agui Clocks 2011-11-05 (20:46) violin, piano, viola, violin, cello Stephen Albert To Wake the Dead (1978) 1993-02-13 (27:24) soprano, violin, conductor Tribute (1988) 1995-04-08 (10:27) violin, piano Treestone (1984) 1991-11-02 (38:15) soprano, tenor, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, trumpet, clarinet, French horn, flute, percussion, piano, conductor Songs from the Stone Harp (1988) 1989-03-18 (11:56) tenor, harp, cello, percussion Treestone (1978) 1984-03-17 (30:22) soprano, tenor, flute, clarinet, trumpet, horn, harp, violin, violin, viola, cello, bass, piano, percussion, conductor Into Eclipse (1981) 1985-11-02 (31:46) tenor, violin, violin, viola, cello, contrabass, flute, clarinet, piano, percussion, trumpet, horn, conductor Distant Hills Coming Nigh: "Flower of the Mountain" 2016-04-30 (16:44) double bass, clarinet, piano, viola, conductor, French horn, violin, soprano, flute, violin, oboe, bassoon, cello Tribute (1988) 2002-01-26 (9:55) violin, piano Into Eclipse [New Version for Cello Solo Prepared -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

2018 Available in Carbon Fibre

NFAc_Obsession_18_Ad_1.pdf 1 6/4/18 3:56 PM Brannen & LaFIn Come see how fast your obsession can begin. C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Booth 301 · brannenutes.com Brannen Brothers Flutemakers, Inc. HANDMADE CUSTOM 18K ROSE GOLD TRY ONE TODAY AT BOOTH #515 #WEAREVQPOWELL POWELLFLUTES.COM Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 408 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2018 available in Carbon Fibre. Orlando! 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] www.wisemanlondon.com MAKE YOUR MUSIC MATTER Longy has created one of the most outstanding flute departments in the country! Seize the opportunity to study with our world-class faculty including: Cobus du Toit, Antero Winds Clint Foreman, Boston Symphony Orchestra Vanessa Breault Mulvey, Body Mapping Expert Sergio Pallottelli, Flute Faculty at the Zodiac Music Festival Continue your journey towards a meaningful life in music at Longy.edu/apply TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ................................................................ 14 From the Convention Program Chair ................................................. 21 2018 Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished Service Awards ........ 22 Previous Lifetime Achievement and Distinguished -

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

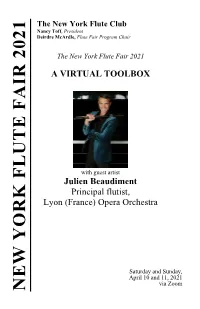

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

Melbourne Suburb of Northcote

ON STAGE The Autumn 2012 journal of Vol.13 No.2 ‘By Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’ Frank Van Straten, Ian Smith and the CATHS Research Group relive good times at the Plaza Theatre, Northcote. ‘ y Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’, equipment. It’s a building that does not give along the way, its management was probably wrote Frank Doherty in The Argus up its secrets easily. more often living a nightmare on Elm Street. Bin January 1952. It was an apt Nevertheless it stands as a reminder The Plaza was the dream of Mr Ludbrook summation of the variety fare offered for 10 of one man’s determination to run an Owen Menck, who owned it to the end. One years at the Plaza Theatre in the northern independent cinema in the face of powerful of his partners in the variety venture later Melbourne suburb of Northcote. opposition, and then boldly break with the described him as ‘a little elderly gentleman The shell of the old theatre still stands on past and turn to live variety shows. It was about to expand his horse breeding interests the west side of bustling High Street, on the a unique and quixotic venture for 1950s and invest in show business’. Mr Menck was corner of Elm Street. It’s a time-worn façade, Melbourne, but it survived for as long as consistent about his twin interests. Twenty but distinctive; the Art Deco tower now a many theatres with better pedigrees and years earlier, when he opened the Plaza as a convenient perch for telecommunication richer backers. -

'Musical Pitch Ought to Be One from Pole to Pole': Touring Musicians and the Issue of Performing Pitch in Late Nineteenth

2011 © Simon Purtell, Context 35/36 (2010/2011): 111–25. ‘Musical Pitch ought to be One from Pole to Pole’: Touring Musicians and the Issue of Performing Pitch in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-century Melbourne Simon Purtell In 1869, English vocal teacher Charles Bishenden complained that the high performing pitch in use in England was ‘ruinous to the voice.’ The high pitch, he reported, was the very reason why many European singers did not perform in Britain.1 ‘For a Continental larynx,’ French soprano Blanche Marchesi (1863–1940) later explained, ‘it is a real torture to sing to different pitches.’ ‘The muscles of a trained larynx act like fine clockwork,’ she wrote, and ‘a change of tone, up or down, alters the precision of their action.’ For this reason, Marchesi believed that ‘musical pitch ought to be one from pole to pole.’2 A standard of performing pitch comprises three fundamental concepts: sound frequency, note-name, and standard. A sound frequency, expressed in Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second (cps), becomes a pitch when assigned to a note in the musical scale, thus determining the pitch of every other note in a particular system of tuning. If, in equal temperament, the A directly above middle C equals 440 Hz, then the C directly above it equals 523.25 Hz. A pitch that is agreed upon, at a given time and place, as the reference point for building and tuning musical instruments to play together, is a pitch standard. Standards of pitch are usually expressed in relation to the note A directly above middle C. -

Salt Lake City August 1—4, 2019 Nfac Discover 18 Ad OL.Pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM

47th Annual National Flute Association Convention Salt Lake City August 1 —4, 2019 NFAc_Discover_18_Ad_OL.pdf 1 6/13/19 8:29 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Custom Handmade Since 1888 Booth 110 wmshaynes.com Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery Wiseman Flute Cases Compact. Strong. Comfortable. Stylish. And Guaranteed for life. All Wiseman cases are hand- crafted in England from the Visit us at finest materials. booth 214 in All instrument combinations the exhibit hall, supplied – choose from a range of lining colours. Now also NFA 2019, Salt available in Carbon Fibre. Lake City! Dr. Rachel Haug Root Katie Lowry Bianca Najera An expert for every f lutist. Three amazing utists, all passionate about helping you und your best sound. The Schmitt Music Flute Gallery offers expert consultations, easy trials, and free shipping to utists of all abilities, all around the world! Visit us at NFA booth #126! Meet our specialists, get on-site ute repairs, enter to win prizes, and more. 00 44 (0)20 8778 0752 [email protected] schmittmusic.com/f lutegallery www.wisemanlondon.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President ................................................................... 11 Officers, Directors, Staff, Convention Volunteers, and Competition Committees ............................................................... -

Buried Treasure

Buried treasure ............................................................................. The colonial woman composer Performers Thursday 4 August 2016, 1pm La Trobe Reading Room State Library Victoria Merlyn Quaife is an Jacinta Dennett is a leading Johanna Selleck is internationally-renowned figure in harp performance a composer, flautist, soprano of great versatility, and teaching in Australia, and musicologist. She performing regularly in and her work is recognised completed a PhD in opera, oratorio, chamber for its rare fusion of poetry composition at the music, lieder and and physicality. Her wide University of Melbourne contemporary music. She is range of performance in 2006. She currently a champion of new music experience includes teaches composition at the and has had many works concerto soloist, recitalist, university, where she is an composed for her. Quaife orchestral and chamber honorary fellow. Selleck is appears on CD with Naxos, musician. Dennett holds published by Cambridge ABC Classics, Tall Poppies, a Master of Fine Arts Scholars Press and has won and Move Records. She in Interdisciplinary Arts numerous awards including is currently Associate Practice and is currently the Percy Grainger Prize Professor and Coordinator undertaking a PhD at the for Composition. Her music of Voice at Sir Zelman University of Melbourne. is recorded on the Move Cowen School of Music, Records and Tall Poppies Monash University. labels. ................................................. Creative Fellow acknowledgments Johanna Selleck would like to express her deep appreciation to State Library Victoria for the opportunity to undertake a Creative Fellowship in the inspiring ..................... surrounds of the Library. 328 Swanston Street Selleck’s thanks are extended to Suzie Gasper, Melbourne Gail Schmidt, Rebecca Anthony, and Dermot McCaul from State Library Victoria, and to performers Merlyn Open 10am–5pm daily Quaife and Jacinta Dennett for their dedication and And until 9pm Thursdays.