Chapter 2 – Existing Transportation Conditions and Major Markets Tier 1 Draft EIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report Pursuing Our Unlimited Potential Annual Report 2012

For the year ended March 31, 2012 Pursuing Our Unlimited Potential Annual Report 2012 Annual Report 2012 EAST JAPAN RAILWAY COMPANY JR East’s Strengths 1 AN OVERWHELMINGLY SOLID AND ADVANTAGEOUS RAILWAY NETWORK The railway business of the JR East Being based in the Tokyo metro- Group covers the eastern half of politan area is a major source of our Honshu island, which includes the strength. Routes originating in the Tokyo metropolitan area. We provide Kanto area (JR East Tokyo Branch transportation services via our Office, Yokohama Branch Office, Shinkansen network, which connects Hachioji Branch Office, Omiya Tokyo with regional cities in five Branch Office, Takasaki Branch directions, Kanto area network, and Office, Mito Branch Office, and intercity and regional networks. Our Chiba Branch Office) account for JR EAST’S SERVICE AREA networks combine to cover 7,512.6 68% of transportation revenue. kilometers and serve 17 million Japan’s total population may be people daily. We are the largest declining, but the population of the railway company in Japan and one of Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, TOKYO the largest in the world. Kanagawa Prefecture, Saitama Prefecture, and Chiba On a daily basis, about 17million passengers travel a network of 70 train lines stretching 7,512.6 operating kilometers An Overwhelmingly Solid and Advantageous Railway Network Annual Report 2012 SECTION 1 OVERALL GROWTH STRATEGY Prefecture) continues to rise, mean- OPERATING REVENUES OPERATING INCOME ing our railway networks are sup- For the year ended March 31, 2012 For the year ended March 31, 2012 ported by an extremely sturdy Others 7.9% Transportation Others 6.1% Transportation operating foundation. -

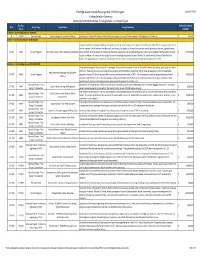

Master HSIPR Selection Sheet 030413 Updates.Xlsx

FRA High‐Speed Intercity Passenger Rail (HSIPR) Program Updated 3/4/2013 Funding Selection Summary (Sorted by State Abbreviation, Funding Source, and Project Type) Funding Potential Estimated State Project Type Project Name Project Summary Source Funding* Alabama ‐ Total Funding Amount: $200,000 AL FY 2009 Planning Project New Passenger Rail Service in Alabama Completion of a feasibility study to restore intercity passenger rail service from Birmingham to Montgomery to Mobile, AL.$ 200,000 Amtrak ‐ Total Funding Amount: $449,944,000 This project will boost capacity, reliability, and speed in one of the most heavily used sections of the Northeast Corridor (NEC). The project will create a 24 mile segment of track between New Brunswick and Trenton, NJ capable of 160 mph train operations with high‐tension catenary, upgraded electric Amtrak ARRA Corridor Program NEC Power, Signal, Track, Catenary Improvements power facilities, and high‐speed rail interlockings that allow express trains to overtake and pass local trains, reducing delays that often affect this track $ 449,944,000 section. In addition, this project makes related track and interlocking investments between Trenton, NJ and Morrisville, PA and at New York Penn Station. The upgraded power facilities will reduce power failures, which are frequently experienced on this segment of the NEC. California ‐ Total Funding Amount: $4,243,143,231 This project encompasses the purchase of 15 passenger rail cars and 4 locomotives for use on the Pacific Surfliner, San Joaquin, and Capitol Corridors in California. These new cars and locomotives will be compliant with standards for equipment that can travel at speeds up to 125 mph established Next Generation Passenger Rail Equipment CA ‐ DOT ARRA Corridor Program pursuant to Section 305 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008. -

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

Submitted by the City of Rensselaer

Downtown Revitalization Initiative “Resurgent Rensselaer” – Submitted by the City of Rensselaer BASIC INFORMATION Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) Region: Capital District Municipality Name: City of Rensselaer Downtown Name: Rensselaer Transit Village County: Rensselaer Vision for Downtown. Provide a brief statement of the municipality’s vision for downtown revitalization. The City of Rensselaer is in the process of reinventing itself as an active waterfront transit village where residents can “Live, Work and Play.” In order to accomplish this mission, the city plans to completely redevelop its waterfront, redefine Broadway as its Main Street, and improve connectivity from new residential, retail, commercial and recreational uses to the Albany/Rensselaer Train Station. Justification. Provide an overview of the downtown, highlighting the area’s defining characteristics and the reasons for its selection. Explain why the downtown is ready for Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) investment, and how that investment would serve as a catalyst to bring about revitalization. The City of Rensselaer is the prime example of a community which is in the midst of rebirth as a modern-day transit village. The city boasts a wonderful location with easy access to regional rail transportation, waterfront recreation, new mixed-use housing developments and a traditional Main Street thoroughfare along Broadway. Moreover, Broadway directly connects the waterfront to a number of historic resources within the city, offering an opportunity to rebrand the city as a modern transit village and historic maritime port of call along the Hudson. A historic impediment to redevelopment along Broadway and the waterfront has been the existence of perceived and potential brownfield sites, as highlighted in the City’s New York State Brownfield Opportunity Areas Program Nomination Study. -

Transportations &

Transportations & map - Overview and detail maps - To Hamamatsu station from airport by trains - Transportation in Hamamatsu city Map overview Tokaido Shinkansen (bullet train) NRT HND Venue, Sep. 12 KIX NGO Venue, Sep. 11 and 13 Accommodation Hotel Crown Palais Hamamatsu To Hamamatsu from airport by trains JR (Japan Railway) Lines Limited express “Narita Express” Tokaido Shinkansen Keikyu Line Tokyo Narita airport (NRT), Terminal 1 (bullet train) Super express Tokyo Haneda airport (HND), International terminal Tokyo Narita airport (NRT), Terminal 2 ・3 “Kodama” or “Hikari” 85min Tokyo Tokyo Shinagawa Shinagawa Shinagawa Shin-Yokohama You can use both Tokyo and Shinagawa to change trains but it is easy to do it at Shinagawa because 80 or 110 min Shinagawa is much smaller station than Tokyo. Shizuoka Meitetsu Line Chubu international airport (NGO) Hamamatsu (Nagoya international airport) 30 or 50 min Nagoya Nagoya Limited express “Haruka” 55 or 70 min - There are many different ways. Here I show Kyoto Kyoto only the most simplest way from each airport. Shin-Osaka Shin-Osaka - You can also use google map to find route 55min including train and bus. Kansai international airport (KIX) Tokaido Shinkansen (bullet train) - Shinkansen, a super express bullet train, is the fastest railway in Japan. - There are so many Tokaido Shinkansen trains between Tokyo and Shin-Osaka station, but trains stopping at Hamamatsu station are limited numbers. - There are 3 types of trains in Tokaido Shinkansen as below. You can use “Hirakari” or “Kodama” to Hamamatsu. Train Detail Duration to Hamamatsu(min) name Tokyo Shinagawa Nagoya Shin-Osaka Nozomi It is fastest but DOES NOT stop at NA NA NA NA Hamamatsu. -

Six Empire Service Trains Will Stop at Grand Central Terminal Instead of New York Penn Station Starting July 10 Through Sept. 1

Six Empire Service Trains Will Stop at Grand Central Terminal Instead of New York Penn Station Starting July 10 through Sept. 1, 2017 Infrastructure Renewal at New York Penn Station As part of the Infrastructure Renewal at New York Penn Station, Amtrak will perform a series of major track and switch renewal projects that will strengthen railroad infrastructure, operations and preparedness -- and ultimately improve reliability at America’s busiest rail hub. The Infrastructure Renewal work accelerates several years of already planned improvements to track, switch and other infrastructure at Penn Station to improve track conditions. This major work will require three northbound and three southbound Empire Service trains to use Grand Central Terminal instead of Penn Station from July 10 – Sept. 1, 2017. If you are getting on or off the following trains at Grand Central Terminal, here are a few things you should know: Trains 230, 233, 235, 236, 239 and 242 Will Stop at Grand Central Terminal Location: Grand Central Terminal is located about a mile north of Penn Station at 89 E 42nd Street, New York, NY, 10017. Transferring between Grand Central Terminal and New York Penn Station: If you are transferring between New York Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal, taxi and local transit are available from both stations, or you can choose to walk. Customers are encouraged to allow extra time if transferring between stations. Schedule Change: Note the new arrival and departure times on your ticket. Trains arriving at and departing from Grand Central Terminal will operate an adjusted schedule. Contact Amtrak for schedule information. -

PRIIA Report

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2020 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2020) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2020 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

No Action Alternative Report

No Action Alternative Report April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. NEC FUTURE Background ............................................................................................................................ 2 3. Approach to No Action Alternative.............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 METHODOLOGY FOR SELECTING NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE PROJECTS .................................................................................... 4 3.2 DISINVESTMENT SCENARIO ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. No Action Alternative ................................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 TRAIN SERVICE ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 4.2 NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE RAIL PROJECTS ............................................................................................................................... 9 4.2.1 Funded Projects or Projects with Approved Funding Plans (Category 1) ............................................................. 9 4.2.2 Funded or Unfunded Mandates (Category 2) ....................................................................................................... -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo-Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report – Discussion Draft 2 1

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo- Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report DISCUSSION DRAFT (Quantified Model Data Subject to Refinement) Table of Contents 1. Project Background: ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Early Study Efforts and Initial Findings: ................................................................................................ 5 3. Background Data Collection Interviews: ................................................................................................ 6 4. Fixed-Facility Capital Cost Estimate Range Based on Existing Studies: ............................................... 7 5. Selection of Single Route for Refined Analysis and Potential “Proxy” for Other Routes: ................ 9 6. Legal Opinion on Relevant Amtrak Enabling Legislation: ................................................................... 10 7. Sample “Timetable-Format” Schedules of Four Frequency New York-Chicago Service: .............. 12 8. Order-of-Magnitude Capital Cost Estimates for Platform-Related Improvements: ............................ 14 9. Ballpark Station-by-Station Ridership Estimates: ................................................................................... 16 10. Scoping-Level Four Frequency Operating Cost and Revenue Model: .................................................. 18 11. Study Findings and Conclusions: ......................................................................................................... -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

20210419 Amtrak Metrics Reporting

NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION 30th Street Station Philadelphia, PA 19104 April 12, 2021 Mr. Michael Lestingi Director, Office of Policy and Planning Federal Railroad Administrator U.S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Mr. Lestingi: In accordance with the Metrics and Minimum Standards for Intercity Passenger Rail Service final rule published on November 16, 2020 (the “Final Rule”), this letter serves as Amtrak’s report to the Federal Railroad Administration that, as of April 10, 2021, Amtrak has provided the 29 host railroads over which Amtrak currently operates (listed in Appendix A) with ridership data for the prior month consistent with the Final Rule. The following data was provided to each host railroad: . the total number of passengers, by train and by day; . the station-specific number of detraining passengers, reported by host railroad whose railroad right-of-way serves the station, by train, and by day; and . the station-specific number of on-time passengers reported by host railroad whose railroad right- of-way serves the station, by train, and by day. Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Jim Blair Sr. Director, Host Railroads Amtrak cc: Dennis Newman Amtrak Jason Maga Amtrak Christopher Zappi Amtrak Yoel Weiss Amtrak Kristin Ferriter Federal Railroad Administration Mr. Michael Lestingi April 12, 2021 Page 2 Appendix A Host Railroads Provided with Amtrak Ridership Data Host Railroad1 Belt Railway Company of Chicago BNSF Railway Buckingham Branch Railroad