The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire from the First Century CE to the Third

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penguin Travel DMC-Bulgaria Address: 9 Orfej Str., 1421 Sofia

Othoman rule.In the monasteries are one of horse for the day 25 % canter, 25% trot, Introduction: the oldest and best preserved religious wall 50 % walk. Six days of riding in the Rodopes –the land of paintings. high peaks and deep river gorges, weird rock The riding starts in Brestovica and formations, lush meadows and dense forests. Itinerary: continues south direction into and up the The green and 225 km (139 mile) long Rhodopa mountain. After leaving the mountain ridge of the Rodopi Mountains is The trip starts from Plovdiv - the encient village and a short steep decline where situated in southern Bulgaria, with 20 percent major town in the tracian valley, famous with the horses walk we pass trough the of the range extending into Greece. The its seven hills and 5000 years of history. After beautiful meadows of the area of Leshten highest peak is around 2,000 m (6,561 ft) high, breakfast there is a short transfer to the enjoying gorgeous views both North to the with the average height around 800 m (2,624 Brestovica village, 20 km away from Plovdiv, Tracian valley and South towards the ft). With their pleasant climate the Rodopi located in the outskirts of the Rhodopa mountain ridges. Here as terrain is opend Mountains are the perfect place for horse riding mountain. The village of Brestovica is famous up and more even the horses can trot and , offering a variety of terrains in which one can with its tradition in the production of high canter again. We have lunch there by experience of all tipes of riding. -

The Crisis and Collapse of the Roman Empire

The Crisis and Collapse of the Roman Empire The Crisis and Collapse of the Roman Empire Lesson plan (Polish) Lesson plan (English) The Crisis and Collapse of the Roman Empire The capture of Rome by the Vandals Source: Karl Bryullo, Zdobycie Rzymu przez Wandalów, between 1833 and 1836, Tretyakov Gallery, licencja: CC 0. Link to the lesson You will learn to define the causes of the crisis of the Roman Empire in the third century CE; telling who was Diocletian and what he did to end the crisis; to describe when was the Roman Empire divided into the East and West Empires; to define what was the Migration Period and how did it influence the collapse of the Western Roman Empire; to define at what point in history the Antiquity ended and the Middle Ages started. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl Nagranie abstraktu The period of “Roman Peace”, ushered in by Emperor Augustus, brought the Empire peace and prosperity. Halfway through the second century CE the Roman Empire reached the peak of its power and greatness. The provinces thrived, undergoing the process of romanization, i.e. the spread of Roman models and customs. It was, however, not an easy task to maintain peace and power in such a large area. In order to keep the borders safe, the construction of the border fortification system, known as the limes was undertaken. Its most widely‐known portion – the over 120 kilometer‐long Hadrian’s Wall – is still present in Britain. That notwithstanding, the Empire was facing ever greater inner problems. The bust of Emperor Augustus Source: Augustus Bevilacqua, Glyptothek, Munich, licencja: Especially in the third century, the state’s CC 0. -

The Ubiquity of the Cretan Archer in Ancient Warfare

1 ‘You’ll be an archer my son!’ The ubiquity of the Cretan archer in ancient warfare When a contingent of archers is mentioned in the context of Greek and Roman armies, more often than not the culture associated with them is that of Crete. Indeed, when we just have archers mentioned in an army without a specified origin, Cretan archers are commonly assumed to be meant, so ubiquitous with archery and groups of mercenary archers were the Cretans. The Cretans are the most famous, but certainly not the only ‘nation’ associated with a particular fighting style (Rhodian slingers and Thracian peltasts leap to mind but there are others too). The long history of Cretan archers can be seen in the sources – according to some stretching from the First Messenian War right down to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Even in the reliable historical record we find Cretan archer units from the Peloponnesian War well into the Roman period. Associations with the Bow Crete had had a long association with archery. Several Linear B tablets from Knossos refer to arrow-counts (6,010 on one and 2,630 on another) as well as archers being depicted on seals and mosaics. Diodorus Siculus (5.74.5) recounts the story of Apollo that: ‘as the discoverer of the bow he taught the people of the land all about the use of the bow, this being the reason why the art of archery is especially cultivated by the Cretans and the bow is called “Cretan.” ’ The first reliable references to Cretan archers as a unit, however, which fit with our ideas about developments in ancient warfare, seem to come in the context of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). -

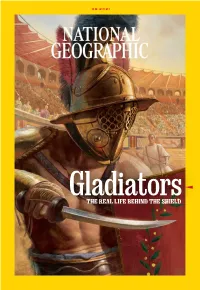

The Real Life Behind the Shield 3

08.2021 Gladiators THE REAL LIFE BEHIND THE SHIELD 3 1 2 Driving discovery further than ever before. National Geographic and Hyundai have teamed up to bring you Outside Academy–an immersive augmented reality (AR) adventure offering in-depth educational experiences from America’s national parks. Visit Yosemite National Park and activate AR hotspots throughout the park on Instagram, or bring the park to you with AR Anywhere. And now, the first-ever TUCSON Plug-in Hybrid takes your sense of discovery further in style, all while keeping in harmony with the environment around you. Reimagining how far your mind will take you, it’s your journey in the first-ever TUCSON Plug-in Hybrid. 1 Unlock the secrets of Yosemite at Yosemite Falls. 2 Learn about the park’s wonders from Tunnel View. 3 Tap to place a bighorn sheep in any meadow. Visit Yosemite Find @NatGeo Search for National Park. on Instagram. the effects. FURTHER AUGUST 2021 On the Cover CONTENTS Ready for combat, a heavily armed Thraex gladiator holds up his shield and sica, a short sword with a curved blade, in the amphitheater at Pompeii. FERNANDO G. BAPTISTA PROOF 1EXPL5ORE THE BIG IDEA The Dog (et al.) Days If we love holidays and we love animals, it’s no surprise that we’d love animal- themed holidays. BY OLIVER WHANG INNOVATOR 28 The ‘Gardening’ Tapir DECODER This animal is key to Space Hurricane reviving Brazil’s wet- A vortex of plasma lands after wildfires, spins up to 31,000 says conservation ecol- miles above Earth. ogist Patrícia Medici. -

The Expansion of Christianity: a Gazetteer of Its First Three Centuries

THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY SUPPLEMENTS TO VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAE Formerly Philosophia Patrum TEXTS AND STUDIES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE AND LANGUAGE EDITORS J. DEN BOEFT — J. VAN OORT — W.L. PETERSEN D.T. RUNIA — C. SCHOLTEN — J.C.M. VAN WINDEN VOLUME LXIX THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY A GAZETTEER OF ITS FIRST THREE CENTURIES BY RODERIC L. MULLEN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullen, Roderic L. The expansion of Christianity : a gazetteer of its first three centuries / Roderic L. Mullen. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13135-3 (alk. paper) 1. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Title. II. Series. BR165.M96 2003 270.1—dc22 2003065171 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 13135 3 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands For Anya This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Introduction ................................................................................ 1 PART ONE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA BEFORE 325 C.E. Palestine ..................................................................................... -

Romes Enemies: Germanics and Daciens No.1 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ROMES ENEMIES: GERMANICS AND DACIENS NO.1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK P. Wilcox | 48 pages | 25 Nov 1982 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780850454734 | English | New York, United Kingdom Romes Enemies: Germanics and Daciens No.1 PDF Book Aurelian established a new college of high priests, under the name Pontifices Dei Solis. We should believe it because later Hesychios wrote about tattooed men in those areas where among others lived also Dacians. Mommsen shows that Julius Caesar was prepared to attack the " Danubian wolves ", being obsessed by the idea of the destruction of the non-Roman religious centers, which represented major obstacles for the Roman colonization. More search options. They did not do only the usual colouring of the body because Plinios reported that those marks and scars can be inherited from father to son for few generations and still remain the same - the sign of Dacian origin. Military uniforms are shown in full colour artwork. Allers Illustrerede Konversations-Leksikon' Copenhagen says that the Morlaks are some of the best sailors in the Austrian navy. But Dichineus is Dicineus as referred by Iordanes, a great Dacian priest and king of the kings. Cesar Yudice rated it liked it Jan 25, This ritual was practiced in Thrace and, most probably, in Dacia. Crisp, tight pages. He lived there for about three or four years. IV of Th. A painted statue left representing a Dacian is found in Boboli. Herodot tells us about "Zalmoxis, who is called also Gebeleizis by some among them". Members Reviews Popularity Average rating Conversations 85 2 , 3. The commander of the Dacians was Diurpaneus , according to the Roman historian Tacitus, a "tarabostes" namely an aristocrat, according to local denomination and to whom the king Duras Durbaneus, would grant his throne soon after Tapae's victory. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

CHAPTER ONE — Aspects of Political and Social Developments in Germania and Scandinavia During the Roman Iron Age

CHAPTER ONE — Aspects of Political and Social Developments in Germania and Scandinavia during the Roman Iron Age 1.1 Rome & Germania 1.1.1 Early Romano-Germanic Relations It is unclear when a people who may be fairly labelled ‘Germanic’ first appeared. Dates as early as the late Neolithic or early Bronze Ages have been suggested.1 A currently popular theory identifies the earliest Germanic peoples as participants in the Jastorf superculture which emerged c. 500 bc,2 though recent linguistic research on early relations between Finno-Ugric and Germanic languages argues the existence of Bronze-Age Germanic dialects.3 Certainly, however, it may be said that ‘Germanic’ peoples existed by the final centuries bc, when classical authors began to record information about them. A fuller analysis of early Germanic society and Romano-Germanic relations would far outstrip this study’s limits,4 but several important points may be touched upon. For the Germanic peoples, Rome could be both an enemy and an ideal—often both at the same time. The tensions created by such contrasts played an important role in shaping Germanic society and ideology. Conflict marked Romano-Germanic relations from the outset. Between 113 and 101 bc, the Cimbri and Teutones, tribes apparently seeking land on which to settle, proved an alarmingly serious threat to Rome.5 It is unclear whether these tribes 1Lothar Killian, Zum Ursprung der Indogermanen: Forschungen aus Linguistik, Prähistorie und Anthropologie, 2nd edn, Habelt Sachbuch, 3 (Bonn: Habelt, 1988); Lothar Killian, Zum Ursprung der Germanen, Habelt Sachbuch, 4 (Bonn: Habelt, 1988). 2Todd, pp. 10, 26; Mark B. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

CALENDARS by David Le Conte

CALENDARS by David Le Conte This article was published in two parts, in Sagittarius (the newsletter of La Société Guernesiaise Astronomy Section), in July/August and September/October 1997. It was based on a talk given by the author to the Astronomy Section on 20 May 1997. It has been slightly updated to the date of this transcript, December 2007. Part 1 What date is it? That depends on the calendar used:- Gregorian calendar: 1997 May 20 Julian calendar: 1997 May 7 Jewish calendar: 5757 Iyyar 13 Islamic Calendar: 1418 Muharaim 13 Persian Calendar: 1376 Ordibehesht 30 Chinese Calendar: Shengxiao (Ox) Xin-You 14 French Rev Calendar: 205, Décade I Mayan Calendar: Long count 12.19.4.3.4 tzolkin = 2 Kan; haab = 2 Zip Ethiopic Calendar: 1990 Genbot 13 Coptic Calendar: 1713 Bashans 12 Julian Day: 2450589 Modified Julian Date: 50589 Day number: 140 Julian Day at 8.00 pm BST: 2450589.292 First, let us note the difference between calendars and time-keeping. The calendar deals with intervals of at least one day, while time-keeping deals with intervals less than a day. Calendars are based on astronomical movements, but they are primarily for social rather than scientific purposes. They are intended to satisfy the needs of society, for example in matters such as: agriculture, hunting. migration, religious and civil events. However, it has also been said that they do provide a link between man and the cosmos. There are about 40 calendars now in use. and there are many historical ones. In this article we will consider six principal calendars still in use, relating them to their historical background and astronomical foundation. -

A Tale of Two Periods

A tale of two periods Change and continuity in the Roman Empire between 249 and 324 Pictured left: a section of the Naqš-i Rustam, the victory monument of Shapur I of Persia, showing the captured Roman emperor Valerian kneeling before the victorious Sassanid monarch (source: www.bbc.co.uk). Pictured right: a group of statues found on St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, depicting the members of the first tetrarchy – Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius and Galerius – holding each other and with their hands on their swords, ready to act if necessary (source: www.wikipedia.org). The former image depicts the biggest shame suffered by the empire during the third-century ‘crisis’, while the latter is the most prominent surviving symbol of tetrar- chic ideology. S. L. Vennik Kluut 14 1991 VB Velserbroek S0930156 RMA-thesis Ancient History Supervisor: Dr. F. G. Naerebout Faculty of Humanities University of Leiden Date: 30-05-2014 2 Table of contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Historiography ............................................................................................................................... 10 1. Narrative ............................................................................................................................................ 14 From -

Religion: Christianity and Zoroastrianism

This page intentionally left blank ROME AND PERSIA IN LATE ANTIQUITY The foundation of the Sasanian Empire in ad 224 established a formidable new power on the Roman Empire’s Eastern frontier, and relations over the next four centuries proved turbulent. This book provides a chronological narrative of their relationship, supported by a substantial collection of translated sources illustrating important themes and structural patterns. The political goals of the two sides, their military confrontations and their diplomatic solutions are dis- cussed, as well as the common interests between the two powers. Special attention is given to the situation of Arabia and Armenia, to economic aspects, the protection of the frontiers, the religious life in both empires and the channels of communication between East and West. In its wide chronological scope, the study explores the role played by the Sasanians in the history of the ancient Near East. The book will prove invaluable for students and non-specialists interested in late antiquity and early Byzantium, and it will be equally useful for specialists on these subjects. beate dignas is Fellow and Tutorin Ancient History at Somerville College, Oxford. Her recent publications include Economy of the Sacred in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor (2002) and she has edited a forthcoming book Practitioners of the Divine: Greek Priests and Religious Officials from Homer to Heliodorus. engelbert winter is Professor of Ancient History at the Uni- versity of Munster.¨ He has participated in numerous field surveys and excavations in Turkey and published many books and articles on Roman–Persian relations and the history and culture of Asia Minor.