Full Investigations and Windshield Surveys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Assessment Agriculture

United States Department of Environmental Assessment Agriculture Forest Service Byway Lakes Enhancement Project August 2013 Hell Canyon Ranger District, Black Hills National Forest Custer & Pennington Counties, South Dakota T02S, R05E Sections 11 T02S, R06E Sections 27, 28 T03S, R05E Sections 15, 22 Horsethief Lake 1938 For Information Contact: David Pickford 330 Mt. Rushmore Road Custer, SD 57730 Phone: (605) 673-4853 Email: [email protected] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large-print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202)720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, or call (800)795-3272 (voice) or (202)720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Table of Contents SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... i CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION -

City of Yankton Commission Meeting to Be Held at the RTEC

CITY OF YANKTON 2015_05_11 COMMISSION MEETING YANKTON BOARD OF CITY COMMISSIONERS Regular City Commission Meeting beginning at 7:00 P.M. Monday, May 11, 2015 City of Yankton Community Meeting Room Located at the Technical Education Center • 1200 W. 21st Street • Room 114 Rebroadcast Schedule: Tuesday @ 7:30pm, Thursday @ 6:30 pm, on channels 3 & 45 I. ROUTINE BUSINESS 1. Roll Call 2. Approve Minutes of regular meeting of April 27, 2014 and Special Meeting of April 20, 2014 Attachment I-2 3. Schedule of Bills Attachment I-3 4. Proclamation: Safe Boating Police Week Motorcycle Safety Attachment I-4 5. City Manager’s Report Attachment I-5 6. Public Appearances II. CONSENT ITEMS 1. Establish Date for Combined City of Vermillion & City of Yankton Meeting Establish 7 p.m. Monday, June 29, 2015, as the time and date for the combined City of Vermillion and City of Yankton Commission meeting to be held at the RTEC. 2. Transient Merchant & Dance License Consideration of Memorandum #15-97 regarding Applications from the Biker Friendly Community Committee for: (A)Transient Merchant License for August 1 2015; (B)Special Events Dance License for August 1, 2015 Attachment II-2 3. Pyrotechnics License Consideration of Memorandum #15-107 in support of Resolution #15-13 for Permission to Host a Public Fireworks Display Attachment II-3 III. OLD BUSINESS 1. Public hearing for sale of alcoholic beverages Consideration of Memorandum #15-88 regarding the request for a Special Events Wine License for 1 day, May 13, 2015, from The Center (Christy Hauer, Executive Director), 900 Whiting Drive, Yankton, S.D Attachment III-1 2. -

THE AFTERMATH of the 1972 RAPID CITY FLOOD Arnett S

THE AFTERMATHOF THE 1972 RAPID CITY FLOOD Arnett S. Dennis Rapid City, South Dakota Abstract. The aftermath of the 1972 Rapid City flood included a controversy over the propriety of cloud seeding on the day of the flood and a lawsuit against the U. S. Government.Preparation of the defense against the suit involved analyses of hourly rainfall accumulations, radar data from the seeded clouds, and possible microphysical and dynamic effects of seeding clouds with powdered sodium chloride (salt). Recent developments in numerical modeling offer some hope of improved understanding of the storm. However, mesoscale systems remain somewhat unpredictable, and realization of this fact has inhibited research dealing with the deliberate modification of large convective clouds. 1. ORIGIN OF THE CONTROVERSY until about 6:00 p.m. This storm was immediately recognized by our meteorologists as dangerous and The Institute of Atmospheric Sciences (IAS) was never seeded by our group," The Governor’s of the South Dakota School of Mines and Tech- office accepted Schleusener’s report and issued nology (School of Mines) conducted two cloud a statement asking the public to refrain from seeding flights at the eastern edge of the Black Hills spreading rumors. An investigative team sent on Friday, 9 June 1972. Late that evening, a flash to Rapid City by the Bureau of Reclamation flood swept down Rapid Creek and devastated (Reclamation) of the U. S. Departmentof the Interior Rapid City. On the following day, the IAS Director, (Interior), which sponsored the IAS cloud seeding Dr. Richard Schleusener, organized a telephone experiments, also reported in an internal memo- "tree," which produced the gratifying news that all randum dated 21 June that cloud seeding did not IAS staff membersand their immediate families cause the flood. -

Riding with a NASCAR Legend

TONIGHT’S CONCERT 7 OF 7 FRIDAY AUG. 9, 2019 10:30 PM 8:30 PM p FREE P ® STURGIS RIDER DAILY DON’T MISS • Motorcycles as art Riding with a NASCAR legend • flaunt girls • Miss Buffalo chip THE RUSTY WALLACE RIDE contest hen Rusty Wallace decides to throw a party, it’s a sure bet it’s going to be a good one, espe- ciallyW when he gathers up his most famous PLAYING and fast NASCAR friends and teams up TONIGHT! with the Legendary Buffalo Chip to raise money for charities! Known for almost 40 years as the best party anywhere, the Chip STURGIS BUFFALO CHIP’S is famous for assembling riders to provide for worthy causes, and bringing NASCAR WOLFMAN JACK STAGE and motorcycles together for a day of great 10:30 PM riding and a bit of community made per- VOLBEAT fect sense. The inaugural Rusty Wallace Ride 8:30 PM kicked off from Rapid City’s Main Street RED FANG Square under bright skies with a meet and greet. The Square made for a beautiful background as fans got autographs from TOMORROW celebrities actor/musician Sean McNabb, 10:30 PM off-road racing Hall of Famer Walker ZAKK SABBATH Evans, quadriplegic off-road racer Evan Evans, and several others including Rusty 8:30 PM himself. A parade of kids on Strider bikes REVEREND HORTON HEAT provided the send-off as 58 riders on 110 motorcycles set off for lunch at the Delmo- STURGIS WEATHER nico Grill in Rapid City before the after- Fri 8/9 Sat 8/10 noon ride to the Buffalo Chip. -

Free Sturgis 2003 Guide

SturgisZone.com http://SturgisZone.com New photos online every single day of the year Sturgis 2003 Schedule Brought to you by the admittedly strange staff at SturgisZone.com Friday August 1st, 2003 The Buffalo Chip Campground 9:00am - 5:00pm - World's Longest Happy Hour ($1 dogs $1 drafts) 4:30pm - The World Pickle Lickin' Federation's Pickle Lickin' Contest 5:00pm - Stage Managers' Choice 9:00pm - 12:00pm - Toadstool Jamboree 12:30am - Miss Buffalo Chip Semi-Finals 1:45am - Captain Jack's Burnout Bridge Party Full Throttle Saloon 7:00am - Open for Breakfast 11:00am - Motley Jackson Band 4:00pm - Blue Jack 9:00pm - Shakedown Broken Spoke Saloon 3:00pm - Joe Santana Band 7:00pm - Dallas Moore Band 11:00pm - AC-DC Tribute Band - Hells Bells Jack Daniel’s - 2nd and Lazelle 8:00am-8:00pm - Open Sturgis Motorcycle Museum & Hall of Fame 12:00noon – 11:00pmJack Daniel’s Lynchburg Live Experience Hot Springs 1st Annual Hot Springs Rally - Allen Ranch, 1 mile South on Hwy 385 (Fall River Road) Saturday August 2nd, 2003 The Buffalo Chip Campground 7:00am - Christian Riders Ministry's Free pancake breakfast & opening prayer 9:00am - Arrival and commencement for the American Veterans Traveling Tribute (Vietnam Wall) 9:00am - 5:00pm - The World's Longest Happy Hour ($1 dogs & $1 drafts) 12:00noon - Steve and Steve and Friends 3:00pm - Arrival of Larry Hall's My Tour 365 - Memorabilia Related to the Vietnam War 4:30pm - The World Pickle Lickin' Federation's Pickle Lickin' Contest 5:00pm - The Dance 6:30pm - Competition dual burn-out pits 7:00pm - Captain Jack 7:45pm - Ze Bond Rocks 8:15pm - The Official Commencement Ceremonies of "THE STURGIS PARTY"™ 8:30pm - JOE BONAMASSA 9:45pm - Geneva 10:20pm - Hank Rotten, Jr. -

June 2011 Hog Express

JUNE 2011 HOGHOGHOG EXPRESSEXPRESSEXPRESS BIGGS CHAPTER #0270 NORTH SAN DIEGO COUNTY H.O.G. Next Chapter CHAPTER CHALLENGE Meeting is Friday JUNE 10, 2011 7:00PM GOES TO … BIGGS! HOG Express Editor: Mary S Asst Editor & Photog: Pat L Road Crew: HOG Officers, Black Sheep, Dave Y San Diego HOG Spring Into Summer Ride Biggs Harley-Davidson 1040 Los Vallecitos Blvd. Suite 113, San Marcos, CA (800) 4-Harley Director We are in the middle of another great riding year. Our Activities Committee has done a very nice job of filling our calendar with interesting rides of varying lengths. They have really listened to the chapter and responded to what the membership wants. The results are shown in the popularity of the local rides. And what can I say about the long distance rides? Other chapters are even copying our rides, down to the same routes and hotels. As Bill E says, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” (Well, he might not have actually said that, but I’m sure he would agree!) Our chapter is gaining a reputation for our enthusiasm and our focus on our core mission of riding and having fun. One indicator of our enthusiasm is how we all come out to the large events we put on our calendar. Last month we had the May Ride and the San Diego HOG Spring into Summer Poker Run. Our chapter came out in force and won the chapter challenges at both events. On a special note, Clint A of the May Ride actually named the May Ride chapter challenge after our own Tom M. -

Download Download

The Journal of Weather Modification 2002 Texas Weather Modification Scientific Management Seeded Control Simple Ratio Increase Prec. Mass 1439.3 kton 667.4 kton 2.16 (1.89) 116 (89) After modeling the increase dropped to 89 % Volume 35 April 2003 WEATHER MODIFICATION ASSOCIATION North American Weather Our weather modification Consultants (NAWC) is the services span the full spectrum, world’s longest-standing from a) feasibility studies to b) private weather modification turn-key design, conduct, and company. evaluation of projects to c) total A recognized leader since technology transfer. By 1950, many consider us the combining practical technical world’s premier company in this advances with field-proven dynamic field. We are proud of methods and operational our sterling record and long list of expertise, we provide expert satisfied customers. assistance to water managers and users in the agricultural, governmental, and hydroelectric communities worldwide. together the best-suited We offer ground-based and/or methods, materials, equipment airborne, summer and winter systems and talent to provide operational and research you with the greatest project programs. Additional specialties value. in extreme storm studies, climatic When you put it all together, surveys, air quality, NAWC is the logical choice meteorological observing for high value weather systems, forensic meteorology modification services. Visit our and weather forecasting, broaden website at www.nawcinc.com for our meteorological perspective. more information, and call us at Whatever your weather (801) 942-9005 to discuss your modification needs, we can help. needs. You can also reach us We will tailor a project to your by email: [email protected]. -

SBCC-Report Revised

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The 730-acre property at Sitting Bull Crystal Caverns (SBCC) is of great significance to the geological history of the Black Hills, as well as the histories of South Dakota tourism and, most importantly, of the Oceti Sakowin (“Great Sioux Nation”). Located about ten miles south of downtown Rapid City on Highway 16, the property sits in the heart of the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa), which are the creation place of the Lakota people. The Sitting Bull Cave system—named after the famed Hunkpapa leader, who is said to have camped on the property in the late 1800s—is located in the “Pahasapa limestone,” a ring of sedimentary rock on the inner edges of the “Racetrack” described in Lakota oral traditions. There are three caves in the system. The deepest, “Sitting Bull Cave,” boasts some of the largest pyramid-shaped “dog tooth spar” calcite crystals anywhere in the world. The cave opened to tourists after significant excavation in 1934 and operated almost continuously until 2015. It was among the most successful early tourist attractions in the Black Hills, due to the cave’s stunning beauty and the property’s prime location on the highway that connects Rapid City to Mount Rushmore. 2. The Duhamel Sioux Indian Pageant was created by Oglala Holy Man Nicholas Black Elk and held on the SBCC grounds from 1934 to 1957. Black Elk was a well-known Oglala Lakota whose prolific life extended from his experience at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 to the publication of Black Elk Speaks in 1932 and beyond. -

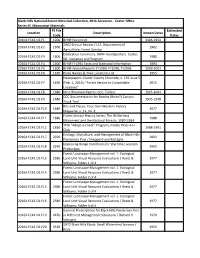

Subject File 1000: Organization and Management

Black Hills National Forest Historical Collection, 2016 Accession - Custer Office Series III. Manuscript Materials FS File Estimated Location Description Known Dates Code Dates 2016A FC42.D2.F1 1200 BHNF Personnel 1906-1954 1962 Annual Review / U.S. Department of 2016A FC42.D2.F2 1600 1962 Agriculture, Forest Service Dedication Ceremony: BHNF Headquarters, Custer, 2016A FC42.D2.F3 1600 1980 SD: Invitation and Program 2016A FC42.D2.F4 1600 BHNF FY1994 Facts and Statistical Information 1994 2016A FC42.D2.F5 1600 BHNF Annual Reports FY1999, FY2000, FY2003 1999-2003 2016A FC42.D2.F6 1630 Place Names & Their Locations List 1955 Newspapers: Custer County Chronicle, v. 135 issue 5 2016A FC42.D2.F7 1630 (Feb. 4, 2015): "Forest Service to Consolidate 2015 Locations" 2016A FC42.D2.F8 1680 Misc Historical Papers: CCC, Timber 1905-2004 CCC Documentation for Bowles (Boles?) Canyon 2016A FC42.D2.F9 1680 1935-1938 Truck Trail Bits and Pieces: Your Own Western History 2016A FC42.D2.F10 1680 1977 Magazine, v. 11, no. 4 Forest Service History Series: The Wilderness 2016A FC42.D2.F11 1680 1988 Movement and the National Forests: 1980-1984 TPIA "Adopt-a-Creek" Program, Knotty Pines 4-H 2016A FC42.D2.F12 1830 1988-1991 Club Ecology, Silviculture, and Management of Black Hills 2016A FC42.D2.F17 2070 2002 Ponderosa Pine / Shepperd and Battaglia Improving Range Conditions for Wartime Livestock 2016A FC42.D2.F18 2240 1942 Production Forest Landscape Management vol. 1: Ecological 2016A FC42.D2.F13 2380 Land Unit Visual Resource Evaluations / Reetz & 1977 Williams; Folder 1 of 4 Forest Landscape Management vol. -

CHIP HAPPENS! Other Venues, the Chip’S Amphitheater Was Brimming Most Evenings

TPW Sep07 180 PG 8/22/07 12:35 PM Page 48 Spearfish. Favorite rally Monday night, but things had been rather slow bands like Foghat, since then. The BoneYard Saloon really is quite an Canned Heat, Jimmy impressive place, complete with food and mer- Van Zant, Pat Travers, chandise vendors and even restrooms with flush Quiet Riot, The Georgia toilets—a rarity at most bike rallies. The venue Satellites, Blue Oyster was off to a slow start this year but has great Cult, Blackfoot, The potential. Marshall Tucker Band, and Steppenwolf were Breakfast of champions scheduled to play every One event that continues to gain in popularity evening during (and a is the Sturgis Builders Breakfast. This notable few days before) the function was the second to be sponsored by rally. I stopped in early Choppers Inc. and was held at the Broken Spoke Wednesday afternoon on Tuesday morning. And this year, the sold-out and, in front of the big, affair didn’t run out of food as it had during their impressive stage I saw a initial offering. More than 30 bike builders and huge, paved expanse artists joined Billy Lane to donate one-of-a-kind with a quad burnout pit and a mechanical bull Sturgis but not much else. The few peo- Continued from page 47 ple present took shelter under the covered outdoor bar. Two inside builders were to construct a bike on bars (one for the general public stage to be given away on Thursday. and one for VIP ticket holders) Although the Black List Tour got were fully air-conditioned and off to a rather shaky start this year, had small stages for more live it’s scheduled to appear in Daytona music. -

FESTIVAL GUIDE PRESENTED by Table of Contents

FREE TAKE ONE! FESTIVAL GUIDE PRESENTED BY Table of Contents Check-In & Entry.....................02 Camping at the Chip...............06 Ride-In/Walk-In Camping.......08 Concert Guide.........................09 Friday, August 6......................10 Saturday, August 7..................11 Sunday, August 8....................12 Monday, August 9...................13 Tuesday, August 10.................14 Wednesday, August 11...........15 CrossRoads.........................16 Camp Zero...............................19 PowerSports Complex...........20 Thursday, August 12..............24 Friday, August 13....................25 Saturday, August 14...............26 Buffalo Chip GarageTM............27 Motorcycles As ArtTM..............28 Bike Shows.............................29 Vendor Guide..........................30 Amenities..............................32 Contact Information Festival Tips & Tricks..............34 Policies & Procedures............36 Buffalo Chip Box Office......................605-347-9000 Jack’s Campers..................................605-999-8781 Buffalo Chip Security Dispatch...........605-720-7938 Cover Art by Russel Murchie 01 WHERE AM I? ENTRY PROCEDURE You are required to wear a wristband or have a printed pass on you at all times while Free inside the venue. Wristbands Parking must be worn on the right wrist (throttle hand). *In the event your wristband shows signs of breaking, you must bring the damaged band BEFORE IT BREAKS OFF to either box office for immediate replacement. DETACHED WRISTBANDS WILL NOT BE REPLACED. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 5:18-cv-05056-JLV Document 1 Filed 08/03/18 Page 1 of 6 PageID #: 1 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF SOUTH DAKOTA 2 WESTERN DIVISION 3 KATHLEEN HANLINE‐LEWIS, 4 CIV. NO.: ________________5:18-cv-5056 Plaintiff, 5 6 vs. 7 ROLAND SANDS, an individual, BUFFALO COMPLAINT CHIP CAMPGROUND, LLC, and POLARIS 8 INDUSTRIES, INC. dba INDIAN 9 MOTORCYCLE COMPANY, 10 Defendants. 11 Plaintiff Kathleen Hanline‐Lewis, by and through her attorneys BEARDSLEY, JENSEN & LEE 12 in the above‐entitled matter and for her Complaint against Defendant states and alleges as 13 14 follows: 15 PARTIES 16 1. Plaintiff Kathleen Hanline‐Lewis is a resident of Las Vegas, Clark County, 17 Nevada and was visiting Sturgis, South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in August, 18 2016. 19 20 2. Based upon information and belief, Defendant Roland Sands is a resident of 21 Long Beach, Los Angeles County, California. 22 3. Based upon information and belief, Defendant Buffalo Chip Campground, LLC is 23 a limited liability company organized under the laws of South Dakota with its principal place of 24 25 business in Sturgis, South Dakota. 26 4. Defendant Polaris Industries, Inc., registered in South Dakota as a foreign 27 corporation, purchased Indian Motorcycle Company in April, 2011 and continues to operate the 28 1 Case 5:18-cv-05056-JLV Document 1 Filed 08/03/18 Page 2 of 6 PageID #: 2 1 business as Indian Motorcycle Company with its principal place of business in Medina, 2 Minnesota. 3 5.