Manual, Part 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo

The Shrine : Notes toward a Study of Neighborhood Festivals in Modern Tokyo By A.W. S a d l e r Sarah Lawrence College When I arrived in Japan in the autumn of 1965, I settled my family into our home-away-from-home in a remote comer of Bunkyo-ku3 in Tokyo, and went to call upon an old timer,a man who had spent most of his adult life in Tokyo. I told him of my intention to carry out an exhaustive study of the annual festivals (taisai) of a typical neighbor hood shrine (jinja) in my area of residence,and I told him I had a full year at my disposal for the task. “Start on the grounds of the shrine/,was his solid advice; “go over every tsubo '(every square foot3 we might say),take note of every stone, investigate every marker.” And that is how I began. I worked with the shrines closest to home so that shrine and people would be part of my everyday life. When my wife and I went for an evening stroll, we invariably happened upon the grounds of one of our shrines; when we went to the market for fish or pencils or raaisnes we found ourselves visiting with the ujiko (parishioners; literally,children of the god of the shrine, who is guardian spirit of the neighborhood) of the shrine. I started with five shrines. I had great difficulty arranging for interviews with the priests of two of the five (the reasons for their reluc tance to visit with me will be discussed below) ; one was a little too large and famous for my purposes,and another was a little too far from home for really careful scrutiny. -

The Reliquaries of Hyrule: a Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time

Press Start The Reliquaries of Hyrule The Reliquaries of Hyrule: A Semiotic and Iconographic Analysis of Sacred Architecture Within Ocarina of Time Jared Hansen University of Oregon Abstract This study is a semiotic and iconographic analysis of the sacred architecture in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (Nintendo, 1998). Through an analysis of the visual elements of the game, the researcher found evidence of visual metaphors that coded three temples as sacred spaces. This coding of the temples is accomplished through the symbolism of progression that matches the design of shrines and cathedrals, drawing on iconography and other symbolism associated with Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sacred architecture. Such indications of sacred spaces highlight the ways in which these virtual environments are designed to symbolize the progression of the player from secular to sacred, much like the player’s progression from zero to hero. By using the architecture and symbolism of the three aforementioned belief systems, Ocarina of Time signifies these temples as reliquaries—that is, sacred places that house reverential items as part of the apotheosis of the player. Keywords Art history; The Legend of Zelda; sacred space; symbolism; temple. Press Start 2021 | Volume 7 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hansen The Reliquaries of Hyrule Introduction The video game experiences that I remember and treasure most are the feelings I have within the virtual environments. -

Shinto Ritual Building Practices

Shinto Ritual Building Practices Philip E. Harding History of Art 681 The Ohio State University Shinto, the native religion of Japan, is a very diverse tradition yet one unified by certain ritual practices. Roughly speaking, Shinto can be divided into “folk Shinto” and “shrine Shinto,” but even within these divisions can be found considerable diversity. Every village has its own local traditions that operate independently from, yet related to the shrine tradition. (The folk activities take place on land owned by the shrine.) Within the shrine system there is also diversity, and today we can readily identify at least eighteen separate cults, each with its own style of shrine building1. Within Japan’s own official histories the shrine tradition, particularly the Imperial shrine tradition, has been given the most attention. This tradition experienced continental influences from China and was the one with which the Japanese upper class identified itself. Japan’s folk traditions, practiced in the locale where they first evolved, have largely gone without reference in Japan’s history of art and architecture. Both traditions, however, embrace many related themes and practices. One can find formal dualities expressed in the design of the folk forms and layouts of shrine buildings, as well as some shared motifs such as a “heart pillar.” Most significantly, both traditions periodically build and re-build sacred structures so that the particular built forms are simultaneously ephemeral and enduring – sharing in a kind of temporal immortality. These periodic rebuilding practices serve to reinforce cultural memory and place individuals into the larger stream of sacred time which transcends the temporal, constantly changing world of mortal time. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Hirohito the Showa Emperor in War and Peace. Ikuhiko Hata.Pdf

00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page i HIROHITO: THE SHO¯ WA EMPEROR IN WAR AND PEACE 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page ii General MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito photographed in the US Embassy, Tokyo, shortly after the start of the Occupation in September 1945. (See page 187) 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page iii Hirohito: The Sho¯wa Emperor in War and Peace Ikuhiko Hata NIHON UNIVERSITY Edited by Marius B. Jansen GLOBAL ORIENTAL 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page iv HIROHITO: THE SHO¯ WA EMPEROR IN WAR AND PEACE by Ikuhiko Hata Edited by Marius B. Jansen First published in 2007 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL LTD P.O. Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 2WP UK www.globaloriental.co.uk © Ikuhiko Hata, 2007 ISBN 978-1-905246-35-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library Set in Garamond 11 on 12.5 pt by Mark Heslington, Scarborough, North Yorkshire Printed and bound in England by Athenaeum Press, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page vi 00 Prelims H:Master Testpages Enigma 6/6/07 15:00 Page v Contents The Author and the Book vii Editor’s Preface -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

What-Kind-Place-Is-Ayabe.Pdf

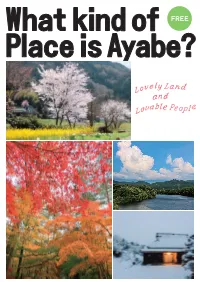

What kind of Place is Ayabe? Lovely Land and Lovable People Table of Contents 1.Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City 2 2) The Land of Ayabe 6 3) The People of Ayabe 9 2. Four Seasons in Ayabe (Events and Flowers) 1)Spring ( from March to May ) 12 2)Summer ( from June to August ) 27 3)Autumn ( from September to November ) 38 4)Winter ( from December to February ) 51 3.Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations in Ayabe 1) Shinto and Shinto Shrines 57 2) Buddhism and Buddhist Temples 63 3) Other Cultural Aspects and Tourist Destinations 69 4) Shops, Cafés, Restaurants etc. 84 Ayabe City Sightseeing Map 88 C260A4AM21 この地図の作成に当っては、国土地理院長の承認を得て、同院発行の数値地図25000(地図画像)を使用した。(承認番号 平22業使、第632号)」 1. Outline of Ayabe City 1) Fundamental Information of Ayabe City Location The middle part of Kyoto Prefecture. It takes about one hour by train from Kyoto. Total Area 347.1 square kilometers Climate It belongs to the temperate zone. The average yearly temperature is 14.8 degrees Celsius. Population 33,821 people in 2015 Working The working population of commerce Population 2,002 people (in 2014) The working population of industry 4,786 people (in 2014) The working population of agriculture 2,914 people (in 2015) Established August 1, 1950 Mayor Zenya Yamazaki (as of 2017) Friendship Cities Jerusalem (Israel), Changshu (China) City Tree Pine City Flower Japanese plum blossoms City Bird Grosbeak (Ikaru) Schools Kyoto Prefectural Agricultural College Ayabe Senior High School Junior high schools 6 schools Elementary schools 10 schools Local Specialties Green tea Matsutake mushroom Chestnut Sweet fish (Ayu) Traditional Japanese hand-made paper (Kurotani Washi) Main Rivers Yura River, Kambayashi River, Sai River, Isazu River, Yata River High mountains M.Tokin (871meters), Mt. -

Description of Fences

Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Description of Fences フェンスの説明 / Description des obstacles Fence 1 – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Hokusai. Author: (Katsushika Hokusai) Original Title: (Kanagawa-oki nami ura) Year: 1829 – 1832 Base/stand: Colour-engraved upon a wooden block. Japanese ukiyo-e master. The Great Wave is the most recognized piece by Japanese painter Katsushika Hokusai, who specializes in ukiyo-e. Published between 1830 and 1833 during the Edo period, it forms part of the collection “Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji”, even though Mount Fuji is the smallest element. The wave references the relentless force of nature, the sea, and the importance this event has in Japan’s economy and its cultural development, given the country is formed by 4 islands. EQUO JUMPTEAM----------FNL-0002RR--_03B 1 Report Created SAT 7 AUG 2021 16 :45 Page 1/7 Equestrian Park Equestrian 馬事公苑 馬術 / Sports équestres Parc Equestre Jumping Team 障害馬術団体 / Saut d'obstacles par équipes SAT 7 AUG 2021 Jump-Off) ジャンプオフ / Barrage Fence 4 – Mascot of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Japanese illustrator Ryo Taniguchi. Manga and gamer references are seen, in representation of the Japanese contemporary visual culture and with a character design inspired by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games’ Logo. The pair of futuristic characters combine tradition and innovation. The name of the Olympics mascot, Miraitowa, fuses the Japanese words for future and eternity. Someity, the Paralympics mascot, is derived from Somei-yoshino, a type of cherry blossom, cherry blossom variety "Someiyoshino" and is a play on words with the English phrase “So mighty”. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Die Riten Des Yoshida Shinto

KAPITEL 5 Die Riten des Yoshida Shinto Das Ritualwesen war das am eifersüchtigsten gehütete Geheimnis des Yoshida Shinto, sein wichtigstes Kapital. Nur Auserwählte durften an Yoshida Riten teilhaben oder gar so weit eingeweiht werden, daß sie selbst in der Lage waren, einen Ritus abzuhalten. Diese zentrale Be- deutung hatten die Riten sicher auch schon für Kanetomos Vorfah- ren. Es ist anzunehmen, daß die Urabe, abgesehen von ihren offizi- ellen priesterlichen Aufgaben, wie sie z.B. in den Engi-shiki festgelegt sind, bereits als ietsukasa bei diversen adeligen Familien private Riten vollzogen, die sie natürlich so weit als möglich geheim halten muß- ten, um ihre priesterliche Monopolstellung halten und erblich weiter- geben zu können. Ein Austausch von geheimen, Glück, Wohlstand oder Schutz vor Krankheiten versprechenden Zeremonien gegen ge- sellschaftliche Anerkennung und materielle Privilegien zwischen den Urabe und der höheren Hofaristokratie fand sicher schon in der späten Heian-Zeit statt, wurde allerdings in der Kamakura Zeit, als das offizielle Hofzeremoniell immer stärker reduziert wurde, für den Bestand der Familie umso notwendiger. Dieser Austausch verlief offenbar über lange Zeit in sehr genau festgelegten Bahnen: Eine Handvoll mächtiger Familien, alle aus dem Stammhaus Fujiwara, dürften die einzigen gewesen sein, die in den Genuß von privaten Urabe-Riten gelangen konnten. Bis weit in die Muromachi-Zeit hin- ein existierte die Spitze der Hofgesellschaft als einziger Orientie- rungspunkt der Priesterfamilie. Mit dem Ōnin-Krieg wurde aber auch diese Grundlage in Frage gestellt, da die Mentoren der Familie selbst zu Bedürftigen wurden. Selbst der große Ichijō Kaneyoshi mußte in dieser Zeit sein Über- leben durch Anbieten seines Wissens und seiner Schriften an mächti- ge Kriegsherren wie z.B. -

A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in The

II SUGIMOTO Hiroshi A Garden in Uji Embodying the Yearning for the Paradise in the West – Byôdô-in Garden – SUGIMOTO Hiroshi Sub-Manager, Historic City Planning Promotion Section, Uji City, JAPAN 1. Creation of Byôdô-in (south-facing temple building) and a pond are located on In the Heian period (794 to 1185), Uji was developed the south-north axis extending from the Nan-mon (south in the southern Heian-kyô (present-day Kyôto) as a gate), and the pond is surrounded by the U shaped temple. residential suburb. The preceding building of Byôdô-in was Byôdô-in is significantly different in these features from the originally built in the early Heian period as a private villa for other two temples. The building style of the Phoenix Hall Minamoto no Tôru, which was later purchased by Fujiwara was taken over by Shôkômyô-in in Toba and Muryôkô-in in no Michinaga. After being bequeathed to his son Fujiwara Hiraizumi, exerting a significant impact on the development no Yorimichi, the villa was converted into a temple in 1052, of Jôdo temples in later years. which coincided with the beginning of the mappô, the age of the degeneration of the Buddha’s law. The main hall of the 2. Byôdô-in Garden villa was then renovated into a Buddhist sanctum and the It is obvious, both from records and the layout, that the Phoenix Hall (Hô-oh-dô) was added in the following year. Phoenix Hall is the main building of the Byôdô-in temple The Fujiwara clan continued expanding the building and, by complex. -

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice

University of Nevada, Reno American Shinto Community of Practice: Community formation outside original context A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Craig E. Rodrigue Jr. Dr. Erin E. Stiles/Thesis Advisor May, 2017 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CRAIG E. RODRIGUE JR. Entitled American Shinto Community Of Practice: Community Formation Outside Original Context be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Erin E. Stiles, Advisor Jenanne K. Ferguson, Committee Member Meredith Oda, Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2017 i Abstract Shinto is a native Japanese religion with a history that goes back thousands of years. Because of its close ties to Japanese culture, and Shinto’s strong emphasis on place in its practice, it does not seem to be the kind of religion that would migrate to other areas of the world and convert new practitioners. However, not only are there examples of Shinto being practiced outside of Japan, the people doing the practice are not always of Japanese heritage. The Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America is one of the only fully functional Shinto shrines in the United States and is run by the first non-Japanese Shinto priest. This thesis looks at the community of practice that surrounds this American shrine and examines how membership is negotiated through action. There are three main practices that form the larger community: language use, rituals, and Aikido. Through participation in these activities members engage with an American Shinto community of practice.