The Global Language of Headwear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hats Off to You, Ladies!

HATS OFF TO YOU, LADIES! by Rhonda Wray 2 Copyright Notice CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this Work is subject to a royalty. This Work is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention and the Berne Convention. RIGHTS RESERVED: All rights to this Work are strictly reserved, including professional and amateur stage performance rights. Also reserved are: motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, information and storage retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into non-English languages. PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND ROYALTY PAYMENTS: All amateur and stock performance rights to this Work are controlled exclusively by Christian Publishers. No amateur or stock production groups or individuals may perform this play without securing license and royalty arrangements in advance from Christian Publishers. Questions concerning other rights should be addressed to Christian Publishers. Royalty fees are subject to change without notice. Professional and stock fees will be set upon application in accordance with your producing circumstances. Any licensing requests and inquiries relating to amateur and stock (professional) performance rights should be addressed to Christian Publishers. Royalty of the required amount must be paid, whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. -

Yiwu Longfashijia Industry&Trade Co

Price list Yiwu LongfaShijia Industry&Trade Co., Ltd TEL: +86-579-85876168 Contact: Andy Wang; TEL: +86-15372998684; E-mail: [email protected] ADD: No. 483 DianKou Village Chengxi Street Yiwu Zhejiang China FOB Net NAME OF head Sample item# PHOTO: finish material QTY (shangha Packing weight(g NO/CTN Carton Size: PRODUCT: size Date: i) usd$ ) Fashion paper paper 90101022 straw fedora hat beige 56cm 1000 $1.65 hangtag 108 60 28*28*78 5-7 days straw; with silver band Fashion paper straw fedora hat paper 90101023 pink 56cm 1000 $1.98 hangtag 120 60 28*28*80 5-7 days with braided straw band Fashion paper paper 90101024 straw fedora hat pink 56cm 1000 $1.82 hangtag 145 60 31*31*70 5-7 days straw with silver band Wide Brim paper Straw Hat straw; 90101025 Floppy Foldable beige 56cm 1000 $2.03 hangtag 180 60 32*32*73 5-7 days flower Summer Beach band flower Sun Hats Womens Wide paper Brim Straw Hat straw; 90101026 FloppyFedora ivory 56cm 1000 $2.03 hangtag 159 60 31*31*75 5-7 days shell Summer Beach band Sun Hats paper fringe Wide straw, Brim Straw Hat 90101027 ivory 56cm fabric 1000 $1.89 hangtag 140 60 32*32*75 5-7 days Floppy Fedora pom pom Beach Sun Hats band 5-7days Spray painting paper paper straw hat straw; 90101028 coffee 56cm 1000 $2.35 hangtag 155 60 31*31*72 with back ribbon fabric band band 5-7days Gold color paper Fedora paper straw, 90101030 straw summer Gold 56cm 1000 $2.82 hangtag 126 60 32*32*76 5-7 days fabric hat with leopard band print fabric band Fedora wide paper brim summer straw, 90101029 Pink 56cm 1000 $2.08 hangtag -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

The BOLLI Journal

The BOLLI Journal Volume Ten 2019-2020 Brandeis Osher Lifelong Learning Institute 1 The BOLLI Journal 2019-2020 Table of Contents Editorial Committee WRITING: Creative Nonfiction Sue Wurster, Production Editor Joanne Fortunato, Artistic Editor Short-Changed, Marty Kafka............................................7 The Kiss, Larry Schwirian...............................................10 Literary Editors The Cocoanut Grove, Wendy Richardson.......................12 Speaking of Shells, Barbara Jordan..... ...........................14 Them Bones, Them Bones Marjorie Arons-Barron , Donna Johns........................16 The Hoover Dam Lydia Bogar , Mark Seliber......................................18 Betsy Campbell Dennis Greene Donna Johns THREE-DIMENSIONAL ART Marjorie Roemer Larry Schwirian Shaker Cupboard, Howard Barnstone.............................22 Sue Wurster Fused Glass Pieces, Betty Brudnick...............................23 Mosaic Swirl, Amy Lou Marks.......................................24 Art Editors WRITING: Memoir Helen Abrams Joanne Fortunato A Thank You, Sophie Freud..............................................26 Miriam Goldman Excellent Work, Jane Kays...............................................28 Caroline Schwirian Reaching the Border, Steve Asen....................................30 First Tears, Kathy Kuhn..................................................32 An Unsung Hero, Dennis Greene....................................33 BOLLI Staff Harry, Steve Goldfinger..................................................36 My -

Book Section Reprint the STRUGGLE for TROGLODYTES1

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 6:33-170 (2017) Book Section Reprint THE STRUGGLE FOR TROGLODYTES1 Boris Porshnev "I have no doubt that some fact may appear fantastic and incredible to many of my readers. For example, did anyone believe in the existence of Ethiopians before seeing any? Isn't anything seen for the first time astounding? How many things are thought possible only after they have been achieved?" (Pliny, Natural History of Animals, Vol. VII, 1) INTRODUCTION BERNARD HEUVELMANS Doctor in Zoological Sciences How did I come to study animals, and from the study of animals known to science, how did I go on to that of still undiscovered animals, and finally, more specifically to that of unknown humans? It's a long story. For me, everything started a long time ago, so long ago that I couldn't say exactly when. Of course it happened gradually. Actually – I have said this often – one is born a zoologist, one does not become one. However, for the discipline to which I finally ended up fully devoting myself, it's different: one becomes a cryptozoologist. Let's specify right now that while Cryptozoology is, etymologically, "the science of hidden animals", it is in practice the study and research of animal species whose existence, for lack of a specimen or of sufficient anatomical fragments, has not been officially recognized. I should clarify what I mean when I say "one is born a zoologist. Such a congenital vocation would imply some genetic process, such as that which leads to a lineage of musicians or mathematicians. -

Of 36 POLICY 117.1 UNIFORMS, ATTIRE and GROOMING REVISED

POLICY UNIFORMS, ATTIRE AND GROOMING 117.1 REVISED: 1/93, 10/99, 12/99, 07/01, RELATED POLICIES: 405, 101, 101.1 04/02, 1/04, 08/04, 12/05, 03/06, 03/07, 05/10, 02/11, 06/11, 11/11, 07/12, 04/13, 01/14, 08/15, 06/16, 06/17, 03/18, 09/18, 03/19, 03/19, 04/21,07/21,08/21 CFA STANDARDS: REVIEWED: As Needed TABLE OF CONTENTS A. PURPOSE .............................................................................................................................. 1 B. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................. 2 C. UNIFORMS ........................................................................................................................... 2 D. PLAIN CLOTHES/ SWORN PERSONNEL ................................................................... 11 E. INSPECTIONS ................................................................................................................... 11 F. LINE INSPECTIONS OF UNIFORMS ........................................................................... 11 G. FLORIDA DRIVERS LICENSE VERIFICATION PROCEDURES ........................... 11 H. MONTHLY LINE INSPECTIONS REPORT AND ROUTING ................................... 12 I. FOLLOW-UP PROCEDURES FOR DEFICIENCY AND/OR DEFICIENCIES ....... 12 J. POLICY STANDARDS/EXPLANATION OF TERMS ................................................. 12 K. GROOMING ....................................................................................................................... 25 Appendix -

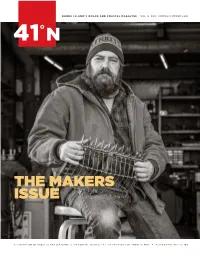

The Makers Issue

RHODE ISLAND'S OCEAN AND COASTAL MAGAZINE VOL 14 NO 1 SPRING/SUMMER 2021 41°N THE MAKERS ISSUE A PUBLICATION OF RHODE ISLAND SEA GRANT & THE COASTAL INSTITUTE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND41˚N spring • A /SEAsummer GRANT 2021 INSTITUTIONFC FROM THE EDITOR 41°N EDITORIAL STAFF Monica Allard Cox, Editor Judith Swift Alan Desbonnet Meredith Haas Amber Neville ART DIRECTOR Ernesto Aparicio PROOFREADER Lesley Squillante MAKING “THE MAKERS” PUBLICATIONS MANAGER Tracy Kennedy not wanting the art of quahog tong making to be “lost to history,” Ben Goetsch, Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council COVER aquaculture coordinator, reached out to us a while ago to ask if we Portrait of Ned Miller by Jesse Burke would be interested in writing about the few remaining local craftsmen sup- ABOUT 41°N plying equipment to dwindling numbers of quahog tongers. That request 41° N is published twice per year by the Rhode led to our cover story (page 8) as well as got us thinking about other makers Island Sea Grant College Program and the connected to the oceans—like wampum artists, salt makers, and boat Coastal Institute at the University of Rhode builders. We also looked more broadly at less tangible creations, like commu- Island (URI). The name refers to the latitude at nities being built and strengthened, as we see in “Cold Water Women” which Rhode Island lies. (page 2) and “Solidarity Through Seafood” (page 36). Rhode Island Sea Grant is a part of the And speaking of makers, we want to thank the writers and photographers National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminis- who make each issue possible—many are longtime contributors whose tration and was established to promote the names you see issue after issue and you come to know through their work. -

A Typical Digger a Digger’S Belongings Newspapers, Magazines and Books Were Full of Advice About What Diggers Should Take to the Goldfields

A typical digger A digger’s belongings Newspapers, magazines and books were full of advice about what diggers should take to the goldfields. A typical digger was a man in his 20s, either unmarried Some even provided lists of supplies. Shops in London, or with a young family. Although doctors and lawyers Sydney and Melbourne offered special digger’s kits. came to the goldfields, most diggers were tradesmen such as blacksmiths, builders, butchers, carpenters and Recommended supplies shoemakers. They were well educated and most could James Bonwick published a guide to the Australian read and write. diggings in 1852. He advised diggers not to take too Some people came to the diggings from nearby much as transport was very expensive. As most would cities and towns by coach or on foot. Others came have to walk to the diggings, they should take only from all over Australia or from overseas. For those what they could carry. Bonwick recommended: seeking their fortune, no distance was too far and • hard-wearing clothes Celebrating success no cost too great. • strong boots Some diggers had jewellery Most of the diggers who came from overseas • waterproof coat and trousers of oilskin made to celebrate their were English, but there were also Welsh, Irish and A portrait to send home success. These brooches • a roll of canvas ‘for your future home’ include many of a diggers’ Scottish diggers. Europeans were also keen to make Diggers who had left their • good jacket for Sundays essential belongings: picks their fortune and came from Germany, Italy, Poland, families far behind were keen • pick, shovel and panning dish and shovels, panning dishes, Denmark, France, Spain and Portugal. -

Spring/Summer 20/21 Featuring the Very Glamorous & Versatile Summer Poncho

ARCHER HOUSE Spring/Summer 20/21 Featuring the Very Glamorous & Versatile Summer Poncho Here is our NEW SPRING/SUMMER COLLECTION. • Stunning range of lightweight and colourful scarves in this season’s fashion colours. • Our new summer Poncho can be worn 3 ways plus it can be used as a lightweight scarf. • Bags and a great range of new summer hats. • Jewellery including bracelets, necklaces and earrings. Our difficult winter is behind us - let’s look forward to a warm, colourful and very successful summer. kind regards, Paul Refer to the jewellery order form for pricing of jewellery highlighted throughout this scarf order form. Order Form : Summer 2020/2021 Invoice : Customer : Phone No. : Date : Email. : Delivery Address : 1SC642 : Block Leaf Print Scarf 3 SC644 : Rectangles and Circles Scarf 100% Viscose, 70 x 180cm Qty Cost Total $ 100% Viscose, 70 x 180cm Qty Cost Total $ White/Orange/Aqua/Yellow $39.90 White/Olive/Mustard/Tan $39.90 SOLD OUT Total $ White/Yellow/Navy/Orange $39.90 Total $ 2 SC643 : Summer Animal Print Scarf 4 SC645 : Spots and Stripes Scarf 100% Viscose, 70 x 180cm Qty Cost Total $ 100% Viscose, 70 x 180cm Qty Cost Total $ White/Grey/Pale Pink $39.90 White/Lemon/Aqua/Navy/ $39.90 Grey White/Pale Blue/Lemon $39.90 White/Orange/Lime/Navy/ $39.90 Total $ Grey Total $ 20-143 : Genuine Stone 20-153 : Leather Bracelet $19.90 each 18-124 : Button Stud 19-146 : Genuine Dainty Freshwater Pearl Hook Earrings $19.90pr Earrings $19.90pr Hook Earrings $19.90pr 2 of 16 Order Form : Summer 2020/2021 Invoice : Customer : Phone No. -

ADDENDUM (Helps for the Teacher) 8/2015

ADDENDUM (Helps for the teacher) 8/2015 Fashion Design Studio (Formerly Fashion Strategies) Levels: Grades 9-12 Units of Credit: 0.50 CIP Code: 20.0306 Core Code: 34-01-00-00-140 Prerequisite: None Skill Test: # 355 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course explores how fashion influences everyday life and introduces students to the fashion industry. Topics covered include: fashion fundamentals, elements and principles of design, textiles, consumerism, and fashion related careers, with an emphasis on personal application. This course will strengthen comprehension of concepts and standards outlined in Sciences, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) education. FCCLA and/or DECA may be an integral part of this course. (Standards 1-5 will be covered on Skill Certification Test #355) CORE STANDARDS, OBJECTIVES, AND INDICATORS Performance Objective 1: Complete FCCLA Step One and/or introduce DECA http://www.uen.org/cte/facs_cabinet/facs_cabinet10.shtml www.deca.org STANDARD 1 Students will explore the fundamentals of fashion. Objective 1: Identify why we wear clothes. a. Protection – clothing that provides physical safeguards to the body, preventing harm from climate and environment. b. Adornment – using individual wardrobe to add decoration or ornamentation. c. Identification – clothing that establishes who someone is, what they do, or to which group(s) they belong. d. Modesty - covering the body according to the code of decency established by society. e. Status – establishing one’s position or rank in comparison to others. Objective 2: Define terminology. a. Common terms: a. Accessories – articles added to complete or enhance an outfit. Shoes, belts, handbags, jewelry, etc. b. Apparel – all men's, women's, and children's clothing c. -

CLOTHING and ADORNMENT in the GA CULTURE: by Regina

CLOTHING AND ADORNMENT IN THE GA CULTURE: SEVENTEENTH TO TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BY Regina Kwakye-Opong, MFA (Theatre Arts) A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AFRICAN ART AND CULTURE Faculty of Art College of Art and Social Sciences DECEMBER, 2011 © 2011 Department of General Art Studies i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the PhD degree and that to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Student‟s Name Regina Kwakye-Opong ............................. .............................. Signature Date Certified by (1st Supervisor) Dr. Opamshen Osei Agyeman ............................ .............................. Signature Date Certified by (2nd Supervisor) Dr. B.K. Dogbe ............................... ................................... Signature Date Certified by (Head of Department) Mrs.Nana Afia Opoku-Asare ................................... .............................. Signature Date i ABSTRACT This thesis is on the clothing components associated with Gas in the context of their socio- cultural functions from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century. The great number of literature on Ghanaian art indicates that Ghanaians including the Ga people uphold their culture and its significance. Yet in spite of the relevance and indispensable nature of clothing and adornment in the culture, researchers and scholars have given it minimal attention. The Ga people‟s desire to combine their traditional costumes with foreign fashion has also resulted in the misuse of the former, within ceremonial and ritual contexts. -

Jewish North African Head Adornment: Traditions and Transition

Jewish North African head adornment: Traditions and Transition Garments, head and foot apparel and jewellery comprise the basic clothing repertoire of man. These vestments are primarily dictated by the wearer's climate and environs and, further, reflect the wearer's ethnic affiliation, social and familial status. Exhibitions and museum collections offer a glimpse into the rich variety of headgear characteristic of diaspora Jews: decorated skuU-caps; headbands and head ornaments; turbans and head scarves, as well as shawls and wraps that covered the body from head to foot. Headdresses exist from Europe, Central Asia, Irán, Iraq, Kurdistan, Yemen, the Balkans and, as shall be focused upon in this text, North África. The head apparel and omamentation under discussion in this article were crafted primarily during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, it must be noted that Jewish garments and head apparel are known to reflect age-old cultural traditions. The artistic assemblage of head adomments was not, however, uniquely Jewish. The design repertoire of eastern Jewish headdresses was given inspiration also from the Muslim environment. Both populations, in continual fear of idolatry, tumed to symbols rich in hidden meanings and to colours ripe with magical properties. The adornments under consideration here were those worn by the Jewish populace during both ceremonial and festive occasions. Festive garb, including omamented headgear, were used in ceremonies of the life cycle ^ and on Jewish holidays ^. Undoubtedly the most exquisite items were worn by the bride and groom on their wedding day. The Song of Songs 3:11 reflects upon the age oíd custom of head adornment: «Go forth, O daughters of Zion, and behold King Solomon with the crown with which his mother crowned him on the day of his wedding...»».