Book Section Reprint the STRUGGLE for TROGLODYTES1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sea Monsters and Real Environmental Threats: Reconsidering the Famous Osborne, ‘Moha-Moha’, Valhalla, and ‘Soay Beast’ Sightings of Unidentified Marine Objects

IMAGINARY SEA MONSTERS AND REAL ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS: RECONSIDERING THE FAMOUS OSBORNE, ‘MOHA-MOHA’, VALHALLA, AND ‘SOAY BEAST’ SIGHTINGS OF UNIDENTIFIED MARINE OBJECTS R. L. FRANCE Dal Ocean Research Group Department of Plant, Food, and Environmental Sciences, Dalhousie University Abstract At one time, largely but not exclusively during the nineteenth century, retellings of encounters with sea monsters were a mainstay of dockside conversations among mariners, press reportage for an audience of fascinated landlubbers, and journal articles published by believing or sceptical natural scientists. Today, to the increasing frustration of cryptozoologists, mainstream biologists and environmental historians have convincingly argued that there is a long history of conflating or misidentifying known sea animals as purported sea monsters. The present paper provides, for the first time, a detailed, diachronic review of competing theories that have been posited to explain four particular encounters with sea monsters, which at the time of the sightings (1877, 1890, 1905, and 1959) had garnered worldwide attention and considerable fame. In so doing, insights are gleaned about the role played by sea monsters in the culture of late-Victorian natural science. Additionally, and most importantly, I offer my own parsimonious explanation that the observed ‘sea monsters’ may have been sea turtles entangled in pre-plastic fishing gear or maritime debris. Environmental history is therefore shown to be a valuable tool for looking backward in order to postulate the length of time that wildlife populations have been subjected to anthropogenic pressure. This is something of contemporary importance, given that scholars are currently involved in deliberations concerning the commencement date of the Anthropocene Era. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Is There an Abominable Snowman? Rennie Bere

'I 11 ! ~ i IJ d J 1 i t 6 I' ""--.-.~-"- 1, Right forefoot of Vrsus arctos isabellinus; 2, right hindfoot of V.a, isabellinus; 3. left hindfoot ofPresbytis entellus; 4, right forefoot ofSelenarctos thibetanus; 5, right hind foot of S, thibetanus; 6, left hindfoot of Gorilla gorilla beringei; 7, hypothesised left hindfoot ofyeti; 8, left hindfoot ofHomo sapiens, Drawings by Jeffery McNeely, first published in 'Oryx' Vo/, 12, No, 1, 100 Is there an Abominable Snowman? Rennie Bere Mysterious footprints in the Himalayan snows have been reported at intervals since early in the 19th Century. So have tales of monsters, whether man-like apes or ape-like men is never quite clear. Similar stories are told in many coun tries, though the Himalayan versions do seem to have more substance than most. They are often accompanied by eye-witness accounts which, however, are difficult to substantiate and inclined to be suspect; unsophisticated people like the Sherpas do not easily distinguish direct evidence from hearsay or re ality from myth. There are few recorded European sightings of any relevance but this is not surprising as climbing parties are rarely silent and have other objectives in mind. The position thus is that if the footprints and genuine sightings are not attributable to animals already known to science-and several large mammals occasionally move up to considerable altitudes in the Hima laya and adjacent ranges-the creature concerned must be the Yeti, the term which will be used in"this article. If such an animal exists it must surely be a primate, presumably an ape not a hominid. -

A Study on Fauna of the Shahdagh National Park

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 5(10)11-15, 2015 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2015, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com A Study on fauna of the Shahdagh National Park S.M. Guliyev Institute of Zoology of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Pass.1128, block 504, Baku, AZ 1073, Azerbaijan Received: June 2, 2015 Accepted: August 27, 2015 ABSTRACT The paper contains information about mammals and insects entered the Red Book of Azerbaijanand the Red List of IUCN distributed in the Azerbaijan territories of the Greater Caucasus (South and North slopes). Researche carried out in the 2008-2012 years. It can be noted that from 43 species of mammals and 76 species of insects entering the Red Book of Azerbaijan 23 ones of mammals ( Rhinolophus hipposideros Bechstein, 1800, Myotis bechsteinii Kunhl, 1817, M.emarqinatus Geoffroy, 1806, M.blythii Tomas, 1875, Barbastella barbastella Scheber, 1774, Barbastella leucomelas Cretzchmar, 1826, Eptesicus bottae Peters, 1869, Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792, Micromys minutus Pollas, 1771, Chionomys gud Satunin,1909, Hyaena hyaena Linnaeus, 1758, Ursus arctos (Linnaeus, 1758), Martes martes (Linnaeus, 1758), Mustela (Mustela) erminea , 1758, Lutra lutra (Linnaeus, 1758), Telus (Chaus) Chaus Gued., 1776, Lynx lynx (Linnaeus, 1758), Pantherapardus (Linnaeus, 1758), Rupicara rupicapra (Linnaeus, 1758), Capreolus capreolus (Linnaeus, 1758), Cervus elaphus maral (Ogilbi, 1840), Capra cylindricornis Bulth, 1840) and 15 species of insects ( Carabus (Procerus) caucasicus -

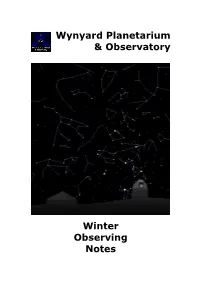

Winter Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory Winter Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye NGC 457 CASSIOPEIA eta Cas Look for Notice how the constellations 5 the ‘W’ swing around Polaris during shape the night Is Dubhe yellowish compared 2 Polaris to Merak? Dubhe 3 Merak URSA MINOR Kochab 1 Is Kochab orange Pherkad compared to Polaris? THE PLOUGH 4 Mizar Alcor Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in winter. North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. To your right is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan standing up on it’s handle. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The top two stars are called the Pointers. Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white-hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you to the left, to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the right are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. Check with binoculars. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 2.0 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Winter Polaris, Kochab and Pherkad mark the constellation Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. -

Global Forest Resources Assessment (FRA) 2020 Azerbaijan

Report Azerbaijan Rome, 2020 FRA 2020 report, Azerbaijan FAO has been monitoring the world's forests at 5 to 10 year intervals since 1946. The Global Forest Resources Assessments (FRA) are now produced every five years in an attempt to provide a consistent approach to describing the world's forests and how they are changing. The FRA is a country-driven process and the assessments are based on reports prepared by officially nominated National Correspondents. If a report is not available, the FRA Secretariat prepares a desk study using earlier reports, existing information and/or remote sensing based analysis. This document was generated automatically using the report made available as a contribution to the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, and submitted to FAO as an official government document. The content and the views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the entity submitting the report to FAO. FAO cannot be held responsible for any use made of the information contained in this document. 2 FRA 2020 report, Azerbaijan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Forest extent, characteristics and changes 2. Forest growing stock, biomass and carbon 3. Forest designation and management 4. Forest ownership and management rights 5. Forest disturbances 6. Forest policy and legislation 7. Employment, education and NWFP 8. Sustainable Development Goal 15 3 FRA 2020 report, Azerbaijan Introduction Report preparation and contact persons The present report was prepared by the following person(s) Name Role Email Tables (old contact) Sadig Salmanov Collaborator [email protected] All Sadig Salmanov National correspondent [email protected] All Introductory text Forests are considered to be one of the most valuable natural resources of Azerbaijan that integrate soil, water, trees, bushes, vegetation, wildlife, and microorganisms which mutually affect each other from biological viewpoint in the course of development. -

Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman by Bernard Heuvelmans, Translated by Paul Leblond, with Afterword by Loren Coleman

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration,Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 604–606, 2016 0892-3310/16 BOOK REVIEW Neanderthal: The Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman by Bernard Heuvelmans, translated by Paul LeBlond, with Afterword by Loren Coleman. San Antonio, TX: Anomalist Books, 2016. 284 pp. $22.95 (paperback). ISBN 978-1938398612. The story of the Minnesota Iceman, the alleged corpse of an unknown hominid, might be conflated by some today, with a more recent iteration on this theme—the claim by charlatans Rick Dyer and Matt Wheaton to have recovered the corpse of a shot and dispatched Bigfoot and their sophomoric attempt to entomb it in a block of ice. It turned out to be an off-the-shelf Bigfoot costume, laced with roadkill. In fact, there was a second attempt by Dyer to pass off an alleged Bigfoot corpse (what is the adage?—“Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice . ”). In the second more notorious incident, Dyer claims to have shot the unfortunate specimen himself outside of Austin, Texas. Eventually, the supposedly taxidermied skin was stuffed and displayed in a crude plywood coffin placed in a garishly decorated trailer, while the skinless corpse itself was reportedly sequestered in a secret lab facility, being examined by unnamed specialists. The resemblance between these tales and the Minnesota Iceman largely ends there, at least as far as the lead-in goes. In 1968, the Iceman incident involved a credentialed and reputable scientist, Bernard Heuvelmans, and a renowned naturalist, Ivan T. Sanderson, who jointly examined Frank Hansen’s exhibit extensively in December 1968. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Flooding Havoc

www.tooeletranscript.com TUESDAY TOOELETRANSCRIPT Fallen sons of Grantsville paid tribute at cemetery See B1 BULLETIN May 31, 2005 SERVING TOOELE COUNTY SINCE 1894 VOL. 112 NO. 2 50 cents Record-breaking deluge pounds Tooele Hail, rain, runoff turn roads into rivers, create flooding havoc by Mark Watson and Karen Hunt STAFF WRITERS Mother Nature saved her best punch for Memorial Day morning. She hit hard, fast and furious. Meteorologists report 3.71 inches of precipitation fell Sunday evening though Monday morning, creating record high rainfall for a 24- hour period. Most fell between 6:30 - 10:30 a.m. Monday. The outburst followed record amounts of snow and rain during the first five months of 2005. It was the beginning of a morning that would create flooding problems for hun- dreds of Tooele homeowners, businesses, schools and relief workers. “We’ve had several dozens of people call with flooding problems,” said Tooele Mayor Charlie Roberts Monday morning. “The problems are all over town. It was just too much water in too short of time.” At the height of the storm, Tooele’s Main Street had been transformed into a shallow river. photography / Troy Boman Ed Criplen hands off a sandbag near the west end of 700 South Monday morning to one of hundreds of volunteers who helped minimize flood damage. Dan Martin (below) who Kathryn Faudree went to lives on 425 West in Tooele, looks out the window in his daughter’s bedroom. The window was blown out by flood waters throwing glass and covering the basement with three work at Tooele Floral on Main feet of flood debris early Monday morning. -

Glosario Teosófico Parte I

Glosario Teosófico Parte I Helena Petronila Blavatski --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Instituto Cultural Quetzalcoatl de Antropología Psicoanalítica, A.C. Portal http://samaelgnosis.net Contacto [email protected] Glosario Teosofico Helena petronila Blavatski INDICE A ...............................................................................................................................................3 B .............................................................................................................................................43 C .............................................................................................................................................61 CH...........................................................................................................................................76 D .............................................................................................................................................85 E ...........................................................................................................................................107 F ...........................................................................................................................................125 G...........................................................................................................................................134 H ...........................................................................................................................................145 -

The Mysterious Phylogeny of Gigantopithecus

Kimberly Nail Department ofAnthropology University ofTennessee - Knoxville The Mysterious Phylogeny of Gigantopithecus Perhaps the most questionable attribute given to Gigantopithecus is its taxonomic and phylogenetic placement in the superfamily Hominoidea. In 1935 von Koenigswald made the first discovery ofa lower molar at an apothecary in Hong Kong. In a mess of"dragon teeth" von Koenigswald saw a tooth that looked remarkably primate-like and purchased it; this tooth would later be one offour looked at by a skeptical friend, Franz Weidenreich. It was this tooth that von Koenigswald originally used to name the species Gigantopithecus blacki. Researchers have only four mandibles and thousands ofteeth which they use to reconstruct not only the existence ofthis primate, but its size and phylogeny as well. Many objections have been raised to the past phylogenetic relationship proposed by Weidenreich, Woo, and von Koenigswald that Gigantopithecus was a forerunner to the hominid line. Some suggest that researchers might be jumping the gun on the size attributed to Gigantopithecus (estimated between 10 and 12 feet tall); this size has perpetuated the idea that somehow Gigantopithecus is still roaming the Himalayas today as Bigfoot. Many researchers have shunned the Bigfoot theory and focused on the causes of the animals extinction. It is my intention to explain the theories ofthe past and why many researchers currently disagree with them. It will be necessary to explain how the researchers conducted their experiments and came to their conclusions as well. The Research The first anthropologist to encounter Gigantopithecus was von Koenigswald who happened upon them in a Hong Kong apothecary selling "dragon teeth." Due to their large size one may not even have thought that they belonged to any sort ofprimate, however von Koenigswald knew better because ofthe markings on the molar. -

TỨ ĐẠI Vs. NGŨ HÀNH Nguyễn Quốc Bảo

LẠI ĂN TỤC NÓI PHÉT ĐŨA VÀ NGUYÊN LÍ NHỊ NGUYÊN PHẦN II: TỨ ĐẠI vs. NGŨ HÀNH Nguyễn Quốc Bảo Thou hast as chiding a nativity As fire, water, earth and heaven can make To herald thee from the womb PERICLES, Shakespeare, Pericles Prince of Tyre. Trong bài Ăn Tục Nói Phét Đũa và Nguyên lí Nhị Nguyên Phần I, có đoạn viết: … Hệ Từ Thượng Truyện viết nguồn gốc của Vũ Trụ: Vô Cực sinh Thái Cực, Thái Cực sinh Luỡng Nghi, Lưỡng Nghi sinh Tứ Tượng Ngũ Hành, Ngũ Hành sinh Bát Quái, Bát Quái là gốc của 64 quẻ Kinh dịch. … Thành thử Âm Dương đi 2 lối khác nhau, Tam Tài Ngũ Hành (Dương, với Số lẻ) và Tứ Tượng Bát Quái (Âm, với Số chẵn). … Âm Dương chuyển hóa theo chu kỳ Ngũ Hành Kim Mộc Thủy Hỏa Thổ, để quy định những quy luật tự nhiên trong xã hội loài người. Trời cao đất rộng, năm qua tháng lại, thời tiết lúc nhập Xuân ấm áp, nên rảnh rang lại xin chư vị bằng hữu cho phép nổi cơn ATNP, để mạn bàn thêm một chuyện vớ vẩn: từ văn hóa Đũa, chủng Bách Việt đã nhận thức lý luận nhị nguyên và vượt đến nguyên lí vĩnh cửu Âm Dương, rồi Âm Dương sinh Tứ Tượng Ngũ Hành. Trong khi đó, Văn hoá Phương Tây trong tiến trình phát triển, nhận thức ra khái niệm Tứ Đại (và Ngũ Đại). Nay xin so sánh Tứ Đại Hoả Địa Khí Thuỷ vs. Ngũ Hành Kim Thủy Mộc Hỏa Thổ, thử tìm hiểu xem hai Văn hóa Đông Tây trong lãnh vực này có điểm trùng hợp hay tương xứng, để có thể đi tới kết luận có một Chân Lý Toàn Năng, giống như đã thảo luận trước đây với Đũa Nguyên lí Nhị Nguyên (Xin xem Đũa phần I).