9 Church in the Wild: Preaching in an Age of Americanized Secularization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

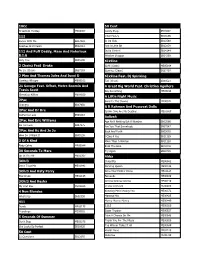

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

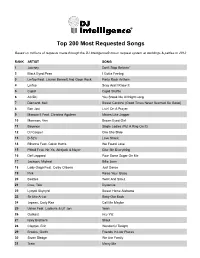

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

No Church in the Wild

No Church in the wild Who was rubbin' the wood like Kiki Shepard Two tattoos, one read "no apologies" Human beings in a mob The other said "love is cursed by monogamy" What's a mob to a king? That's somethin' that the pastor don't preach What's a king to a god? That's somethin' that a teacher can't teach What's a god to a non-believer? When we die, the money we can't keep Who don't believe in anything? But we prolly spend it all 'cause the pain ain't cheap, preach We make it out alive All right, all right Human beings in a mob No church in the wild What's a mob to a king? What's a king to a god? Tears on the mausoleum floor What's a god to a non-believer? Blood stains the Coliseum doors Who don't believe in anything? Lies on the lips of a priest Thanksgiving disguised as a feast We make it out alive Rollin' in the Rolls-Royce Corniche All right, all right Only the doctors got this, I'm hidin' from police No church in the wild Cocaine seats No church in the wild All white like I got the whole thing bleached No church in the wild Drug dealer chic No church in the wild I'm wonderin' if a thug's prayers reach Is Pious pious 'cause God loves pious? Socrates asks, "whose bias do y'all seek?" All for Plato, screech I'm out chere' ballin', I know y'all hear my sneaks Jesus was a carpenter, Yeezy, laid beats Hova flow the Holy Ghost, get the hell up out your seats, preach Human beings in a mob What's a mob to a king? What's a king to a god? What's a god to a non-believer? Who don't believe in anything? We make it out alive All right, all right No church in the wild I live by you, desire I stand by you, walk through the fire Your love, is my scripture Let me into your encryption, yeah yeah Coke on her black skin made a stripe like a zebra I call that jungle fever You will not control the threesome Just roll the weed up until I get me some We formed a new religion No sins as long as there's permission' And deception is the only felony So never fuck nobody without tellin' me Sunglasses and Advil Last night was mad real Sun comin' up 5 a.m. -

Re-Imagining Ecclesiology: a New Missional Paradigm for Community Transformation

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 4-2021 Re-Imagining Ecclesiology: A New Missional Paradigm For Community Transformation Michael J. Berry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin Part of the Christianity Commons GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY RE-IMAGINING ECCLESIOLOGY: A NEW MISSIONAL PARADIGM FOR COMMUNITY TRANSFORMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY MICHAEL J. BERRY PORTLAND, OREGON APRIL 2021 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Michael J. Berry has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on April 29, 2021 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership in the Emerging Culture Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: W. David Phillips, DMin Secondary Advisor: Karen Claassen, DMin Lead Mentor: Leonard I. Sweet, PhD Copyright © 2021 by Michael J. Berry All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife, Andra and to our daughters, Ariel and Olivia. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special thanks for everyone’s support and assistance to get me through this process: Dr. Len Sweet, Donna Wallace, Dr. David Phillips, Dr. Loren Kerns, Dr. Clifford Berger, Dr. Jason Sampler, Rochelle Deans, Dr. David Anderson, Dr. Tom Hancock, Patrick Mulvaney, Ray Crew, and especially Tracey Wagner. iv EPIGRAPH The baptism and spiritual -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Steal the Show in SXSW Performance

Lifestyle FRIDAY, MARCH 14, 2014 Kanye, Jay Z steal the show in ‘Honky Tonk Women’ SXSW performance amsung got its money’s worth from Jay Z too dirty for and Kanye West. Two of rap’s top stars com- Sbined for a powerful, hit-filled two-hour show Wednesday night and yesterday morning China as song ‘vetoed’ during South By Southwest, allowing Samsung to steal some of iTunes’ luster at the annual music he sexual lyrics of “Honky Tonk Women” the reaction from the Shanghai audience was conference and festival. Samsung announced the were apparently too much for China’s muted. “He didn’t play it for shock,” said Austin Music Hall show early this week and Communist fathers as the Rolling Stones Andrew Chin, a local arts writer who attended. scheduled the pair at the same time as the iTunes T Festival’s hip-hop night that featured Kendrick said the chart-topping song was “vetoed” for “People were just excited to see the Stones.” Lamar and ScHoolboy Q at the very nearby ACL their second ever show in the country on China censors content it deems to be politi- Moody Theater. The performance came a few Wednesday. “About now we’d usually play cally sensitive or obscene. Authorities have weeks after West called out Apple CEO Tim Cook something like ‘Honky Tonk Women’... but it’s been especially sensitive about live concerts been vetoed,” front man Mick Jagger said at since Bjork chanted “Tibet” during her song Wednesday’s show, according to a posting on “Declare Independence” in 2008. -

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de kunsten: audiovisuele kunsten Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Arts: Audiovisual Arts Academic year 2017- 2018 Doctorandus: Stoffel Debuysere Promotors: Prof. Dr. Steven Jacobs, Ghent University, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Dr. An van. Dienderen, University College Ghent School of Arts Editor: Rebecca Jane Arthur Layout: Gunther Fobe Cover design: Gitte Callaert Cover image: Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep (1977). Courtesy of Charles Burnett and Milestone Films. This manuscript partly came about in the framework of the research project Figures of Dissent (KASK / University College Ghent School of Arts, 2012-2016). Research financed by the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent. This publication would not have been the same without the support and generosity of Evan Calder Williams, Barry Esson, Mohanad Yaqubi, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Sarah Vanhee, Christina Stuhlberger, Rebecca Jane Arthur, Herman Asselberghs, Steven Jacobs, Pieter Van Bogaert, An van. Dienderen, Daniel Biltereyst, Katrien Vuylsteke Vanfleteren, Gunther Fobe, Aurelie Daems, Pieter-Paul Mortier, Marie Logie, Andrea Cinel, Celine Brouwez, Xavier Garcia-Bardon, Elias Grootaers, Gerard-Jan Claes, Sabzian, Britt Hatzius, Johan Debuysere, Christa -

Industry Panels

Treefort Music Fest - Industry Panels The Friday, Saturday, and Sunday of Treefort, we’re putting on a series of music industry panels that will teach you the ins and outs of music supervision as well as the future of music discovery and record labels: INSIDE MUSIC SUPERVISION Friday, March 24th 3:00-4:30 @ JUMP’s Inspire Studio Five veteran music supervisors discuss how songs get selected for films, TV shows, video games, and more. MUSIC SUPERVISION LISTENING SESSION Saturday, March 25th 12:00- 12:50 @ JUMP’s Inspire Studio Watch the music supervision process unfold live and learn how this mysterious process works. INDEPENDENT MUSIC IN 2017: STATE OF THE INDUSTRY Sunday, March 26th 12:00-1:00 @ the Owyhee President of the label Kill Rock Stars leads a discussion about the ever changing music industry and where it’s going. THE FUTURE OF MUSIC DISCOVERY Sunday, March 26th 1:30-2:30 @ the Owyhee A conversation about how fans are discovering artists now and into the future. You can check all the panel details here. The purpose of Saturday’s panels is to show you how music supervisors think, listen to music, and choose tunes for films, TV shows, commercials, and other projects. During this session, the supervisors will listen to songs from Treefort artists, discuss why the song may or may not make sense for a project the supervisor has worked on, and give some feedback to the artist. This could be a good opportunity for you to get feedback on your music and get it in front of music supervisors. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Never Change 2.1

Never Change 2.1: A Look at Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution kashema h. www.kashema.com Never Change 2.1: A look Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution By kashema h. “Intro” Jay-Z’s classic album Reasonable Doubt (1996) turned 20 years old this summer but it has been two years since he has released another album. He released “Spiritual” after the extrajudicial killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Jay is featured on the remix of “All the Way Up” and teamed up with DJ Khaled and Future to create “I Got the Keys.” Back in April, Mr. Carter made a cameo on his wife’s Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade as a family man. The last time we saw the lyricist in full rap mode (e.g. album, singles and tour) was for Magna Carta Holy Grail in 2013. The promotional On The Run trailer for the married couple’s tour stars Jay-Z and Beyoncé as bank robbers à la Bonnie and Clyde, and features all kinds of guns, ski masks, shady figures, cop chases and a line-up. In 2014, I started to think about Jay’s past criminal life as a drug dealer, and his references to it on his records. I let the thing between my eyes analyze Jay’s skills, then put it down—type Braille...you feel me? Last month, the rapper narrated the New York Times Op-Ed: “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail.” I went back to my study of Jay-Z and his lyrics with a more critical eye.