The National Conference on State Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Benjamin Harrison: from Military Base to Indiana State

FORT BENJAMIN HARRISON: FROM MILITARY BASE TO INDIANA STATE PARK Melanie Barbara Hankins Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University April 2020 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D., Chair ____________________________________ Rebecca K. Shrum, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Anita Morgan, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements During my second semester at IUPUI, I decided to escape the city for the day and explore the state park, Fort Benjamin Harrison State Park. I knew very little about the park’s history and that it was vaguely connected to the American military. I would visit Fort Harrison State Park many times the following summer, taking hikes with my dog Louie while contemplating the potential public history projects at Fort Harrison State Park. Despite a false start with a previous thesis topic, my hikes at Fort Harrison State Park inspired me to take a closer look at the park’s history, which eventually became this project. Finishing this thesis would have been nearly impossible without the encouragement and dedication of many people. First, I need to thank my committee: Dr. Philip Scarpino, Dr. Rebecca Shrum, and Dr. Anita Morgan for their criticism, support, and dedication throughout my writing process. I would especially like to thank my chair, Dr. Scarpino for his guidance through the transition of changing my thesis topic so late in the game. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places _ j,, -,-4 Registration Form HISTORY This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties antf'djstricts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register BullefifneA). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Shakamak State Park Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number 6165 West State Rn?H 48 N/A D not for publication city or town .Tasonville___________ ———H vicinity State Indiana_______ COde TN county Clay code zip code 47418 3. State/Federal Agency Certification "I As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this H nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property K meets D does not meet the Natjonal Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally £3 statewide J^r loyally. -

The Indianapolis Times HOME Increasing Cloudiness and Warmer Tonight, Becoming Unsettled Tuesday

Complete Wire Reports of UNITED PRESS, The Greatest World-Wide News Service The Indianapolis Times HOME Increasing cloudiness and warmer tonight, becoming unsettled Tuesday. S SCAIPPS~-JIOWARr>7k Outside Marlon Entered as Second-Class Matter County 8 Cents VOLUME 40—NUMBER 2 INDIANAPOLIS, MONDAY, MAY 14,1928. at Postoffice, Indianapolis TWO CENTS Fickle NINETEEN / Fate Expert Yeggs ON DIE By Blast Pettis TO FACE QUIZ United LEWIS, Press DAVE Safe WATSON NEW YORK, May 14.—Grief reigned in two homes today because of Mother’s day. A BY VIOLENCE daughter’s forgotten promise RACE DRIVER, CHARGES OF DAWES ‘DEAL’ to her mother of a Mother’s day visit is believed to have lead Mrs. Leila McKillop, 48. OVERSTATE to attempt suicide by gas. She NEWSPAPERS HERE is WITH in serious IS GUNVICTIM condition. Arising early Sunday to cele- Five Persons Killed Gary brate the day, May Driscoll, at 26, fell to her death from the Famed Speedway Star Is Agreement With Fairbanks and Shaffer When Train Strikes kitchen window of their third floor apartment. Found in Cabin, Bullet Alleged, Senator to Grab Delegation Auto. A desire to pay a visit to his Through mother’s grave, brought Joseph Head. to Help Vice President. Richatsky, escaped convict, back to his cell. He was ar- BLAST TOLL STILL FOUR rested as he knelt at the grave PROBE MURDER THEORY of his mother in Linden. FAVORITE SON BOOM SEEMS DYING In November, 1927, Richat- Two Fatalities Due to sky, made a sensational escape Auto Pilot Here from Flushing police court by Due This Headquarters Reported Dropping Burns knocking down a 65-year-old Here as Swell Week- ' Week; Scene of Death attendant. -

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Administrative History

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Administrative History Lincoln Boyhood Administrative History "THERE I GREW UP ..." A History of the Administration of Abraham Lincoln's Boyhood Home Jill York O'Bright Regional Historian, Midwest Region 1987 National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS libo/adhi/adhi.htm Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/adhi/adhi.htm[2/26/2014 5:01:07 PM] Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Administrative History (Table of Contents) Lincoln Boyhood Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROLOGUE Chapter 1. Early Efforts to Memorialize Nancy Hanks Lincoln Chapter 2. The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Phase I Chapter 3. The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Phase II Chapter 4. State Management of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Chapter 5. The Creation of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Chapter 6. Administration and Staffing Chapter 7. Developing the National Memorial Chapter 8. Maintaining the Memorial Chapter 9. Interpretation APPENDIXES Appendix A. Act Authorizing Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Appendix B. Maintenance Guide Prepared by Architect Richard Bishop for the Memorial Building Appendix C. Summary of Land Acquisition Appendix D. Partial Listing of Television Program Titles Appendix E. Ministers Participating in the A Christian Ministry in the National Parks (ACMNP) Program Appendix F. Lincoln Day Speakers Appendix G. List of Permanent Employees of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Appendix H. Managers of the Indiana Lincoln Park BIBLIOGRAPHY http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/adhi/adhit.htm[2/26/2014 -

Download Download

Conservation of Recreational and Scenic Resources Howard H. Michaud, Purdue University Introduction The concept of preservation of a natural area for recreational use, or for its scenic value, seems a paradox to many people. Natural resources are commonly thought of only in the sense that they yield material products. That state and national parks should remain in- violate, its forests uncut, its wildlife protected,—in fact, all commercial exploitation to be forbidden is not universally appreciated. It is true that our civilization thrives on effective use of material resources. But the need for satisfying spiritual values is just as great. Recreational lands set aside as parks yield the great cultural and in- spirational products of knowledge, refreshment, and esthetic enjoyment equally needed by all people. Mission 66, a name applied to a long-range plan for the National Parks, describes the function of the parks as follows: "As our vacation lands, they bring enjoyment and refreshment of mind, body, and spirit to millions of Americans each year. "It is the history of America and if its youngsters could but journey through the whole system from site to site, they would gain a deep understanding of the history of their country; of the natural processes which have given form to our land, and of men's actions upon it from distant prehistoric times." For those who must ascribe an economic value to all resources, parks do contribute materially to the national economy. The American Automobile Association calls the parks the primary touring objective of the American public. The unique situation of the National Parks is that while we preserve them and use them for their inherent, non- commercial values, they are contributing directly to the economic life of the Nation. -

Outdoor Indiana

p II]"Ai #1I director's.r Page THE MEN AND WOMEN of the Indiana Department of Conservation hope you will enjoy Indiana this year. Our state parks, memorials, forests, lakes and rivers offer an abundance of variety and value to you in the constructive use of your leisure time. We invite you to enjoy the recreational facilities and the vacation pleasures to be found at the properties we maintain and in the com- munities nearby. We urge you to enjoy our Conservation properties, appreciate them, and understand how they are supported for present use as well as maintained as our heritage for future Hoosiers. Some of the fascinating opportunities for enjoyment of Indiana are de- scribed or mentioned in this issue of OUTDOOR INDIANA. Many other such opportunities can be discovered by visiting a state park-you can surely acquire an ever-increasing knowledge of our wonderful state by careful observation of the material available at each state park. We are particularly pleased to offer this issue of OUTDOOR INDIANA as a tour and travel edition. This has been made possible through the combined efforts of the Tourist Assistance Council, Indiana Department of Commerce and Public Relations, the many fine people who have contributed the articles and illustrationscontained herein, and the personnel of the several divisions of the Indiana Department of Conservation. Additional copies of this issue, distributed at various places throughout the state to out-of-state travelers as well as to Hoosiers not regularly receiving this magazine, have been procured and made available without cost to the State of Indiana by business and civic organizationsand by individuals as a public service. -

Coastal Parks for a Metropolitan Nation

COASTAL PARKS FOR A METROPOLITAN NATION: HOW POSTWAR POLITICS AND URBAN GROWTH SHAPED AMERICA’S SHORES by Jacqueline Alyse Mirandola Mullen A Dissertation Submitted to the University at Albany, State University of New York in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences Department of History 2015 UMI Number: 3707302 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3707302 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Abstract Between 1961 and 1975, the United States established thirteen of the nation’s fourteen National Seashores and Lakeshores. This unprecedented, nation-wide initiative to conserve America’s coasts transformed how the National Park Service made parks, catalyzed the shift in conservation definitions in America, and created new conservation coalitions that paved the way for the environmental movement. The Department of the Interior began shoreline park establishment as a concerted effort to protect the nation’s more natural shores from the tourist development rapidly covering American coasts in the post-World War II period. The Park Service’s urgency on coastal conservation arose from concerns of overdevelopment, overpopulation, and overuse. -

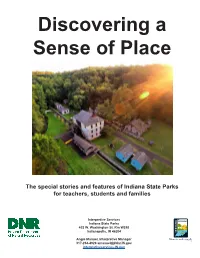

Discovering a Sense of Place

Discovering a Sense of Place The special stories and features of Indiana State Parks for teachers, students and families Interpretive Services Indiana State Parks 402 W. Washington St. Rm W298 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Angie Manuel, Interpretive Manager 317-234-4926 amanuel@#dnr.IN.gov interpretiveservices.IN.gov The special stories and features of Indiana State Parks for teachers, students and families Discovering a Sense of Place Where nature and history come together Why should I care about wildlife? What lessons can we learn from our past? What is the real value of the public land we manage? How will our actions impact the future of these unique places? We encourage questions like these from students, teachers and families as we tell the stories of plants, animals, water, soils and history at our Indiana State Parks. These are our stories......... This booklet provides an overview of the main messages that we interpret at each of our sites. These stories are presented in many ways. We introduce these themes in campground programs for families, exhibits in interpretive centers, wayside signage and environmental education programming for schools, scouts and other groups. This booklet is not just for teachers! If your group visits us for a planned program with an interpreter, we can connect one or more of our site messages with the topic(s) you are covering in your classroom or meeting time. Use this booklet to help you decide which of our properties’ messages and resources best match the topic and concepts you are introducing to your students. The booklet can also serve as a source of basic information about the natural and cultural resources at each state park or big lake. -

CY20 Arts in the Parks and Historic Sites Grant Recipients

CONTACT Indiana Arts Commission 100 N Senate Avenue, Rm N505 Indianapolis, IN 46204 317 232-1268 CY20 Arts in the Parks and Historic Sites Grant Recipients Program Description Arts in the Parks and Historic Sites is a program of the Indiana Arts Commission (IAC) in partnership with Indiana State Parks and the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites. The IAC is an agency of State Government funded by the Indiana General Assembly and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency. On behalf of the people of Indiana, the IAC advocates engagement with the arts to enrich the quality of individual and community life. The IAC is governed by a 15 member board of gubnernatorial appointees and serves all citizens and regions of the state. John Arnold Marion County Indiana Limestone Carving Workshop Spring Mill State Park June 2020 $3,000 Highlighting Indiana’s history, culture, and the natural resource limestone, this workshop will teach the strength, durability, beauty, and plasticity of limestone. The free workshop allows individuals first-hand experience of stone carving that’s been done for generations in Indiana, creating their own stone carving to take home. Arts for Learning Marion County Indiana’s Living Folklife Traditions Mounds State Park May 2020 $2,649 Indiana’s Living Folklife Traditions is a celebration and exploration of the cultural traditions of the region. Activities include yoga for mindfulness, plant and insect observational drawing, nature mandala making, basket weaving, pottery making, and a music performance during the park’s Annual Plant Sale. Arts Place, Inc. Jay County Arts in the Parks at the Limberlost Limberlost State Historic Site June 2020 $3,000 Arts in the Parks at Limberlost will be offered at the home of Gene Stratton-Porter. -

INDIANA NEWS 92 March/April 2018 Association of Indiana Counties Inc

INDIANA NEWS 92 Volume 24 Number 2 March/April 2018 The Impact of Parks ON INDIANA COMMUNITIES Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2051 Indiana Indianapolis, TWG, INC. TWG, U.S. POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S. 101 West Ohio Street, Suite 1575 Suite Street, Ohio West 101 STANDARD PRESORTED Association of Indiana Counties Inc. Counties Indiana of Association Heavy responsibilities. Plenty of pitfalls. Losing your immunity; contracting without proper precautions; dealing with employees; accepting grants, gifts or subsidies without knowing the consequences; or thinking good intentions will outweigh bad results is fraught with risks you have to manage… or trouble will surely come calling. You don’t have to figure it out alone. AIC endorsed for over 25 years. Bliss McKnight’s insurance and risk management programs include knowledgeable people to help you 800-322-3391 avoid “getting into trouble”. [email protected] AIC-8x11-PRESS v2.indd 1 1/19/16 3:49 PM What’s Inside Calendar Vol. 24 Number 2 March/April 2018 MAY 8 Primary Election Day What’s Inside 22 Budget & Finance II Institute Course 22-25 Auditors Spring Conference – Hilton, 3 Local Parks – A Vital Ingredient for Thriving Ft. Wayne Communities 28 Memorial Day By David Bottorff JUNE 4 The Cost of Being a Good Host TBD AIC Board Meeting By Ryan Hoff 13 Legal and Ethical Institute Course 14-16 Coroners’ Training Conference – 6 Indiana State Parks – Past, Present and Future Sheraton Hotel & Suites By Benjamin Clark JULY 4 Independence Day Extras 13-16 NACo Annual Conference, Nashville, TN AIC 2018 Award Applications 18 Budget & Finance II Institute Course 9-11 12 AIC 2018-2019 District Officers: AUGUST Elected to Serve You 8-10 Treasurers Annual Conference 15 Communications Institute Course 13 AIC 2018 Fourth Grade Essay Winners 23 AIC Board Meeting 15-16 AIC 2018-2019 Indiana College Scholarship Applications indianacounties.org SEPTEMBER 3 Labor Day 16-19 AIC’s 60th Annual Conference Stay Connected. -

Samuel Elliott Perkins Family Collection, 1835–1947

Collection # M0225 SAMUEL ELLIOTT PERKINS FAMILY COLLECTION, 1835–1947 Collection Information Biographical Sketches Scope and Content Note Series Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Pamela Tranfield, 1998 Revised by Greg Hertenstein, Robert W. Smith, and Dorothy A. Nicholson March 2012 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF Manuscript Materials: 1 document case, 2 bound volumes COLLECTION: Visual Materials: 2 boxes of photographs, 1 box of 4x5 glass plates, 1 box of 5x7 glass plates, 2 boxes of lantern slides, 2 envelopes of 120mm acetate negatives Printed Materials: 1 pamphlet COLLECTION 1835–1947 DATES: PROVENANCE: Gifts of Samuel E. Perkins, IV, Culver, Indiana: 1975, 1976, 1978, 1981, 1988, 1993, 1994 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED Perkins, Samuel Elliott, 1811-1879, A digest of the decisions of HOLDINGS: the Supreme Court of Indiana [1817-1856]: ... General Collection: KFI3045.1 .P47 1858 Thornbrough, Emma Lou, Judge Perkins, the Indiana Supreme Court, and the Civil War. Pamphlet Collection E506 .T46 1964 Nature Study Club of Indiana. Yearbook, Pamphlet Collection: QH1 .N28 ACCESSION 1975.0416, 1976.0625, 1976.0920, 1978.0406, 1981.1213, NUMBER: 1988.0160, 1993.0418, 1994.0028 NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES Samuel Elliott Perkins (1811–1879) was born in Vermont to John Trumbull and Catherine (Willard) Perkins. Orphaned at an early age he was adopted and raised by a William Baker in Conway, Massachusetts. -

Full Beacher

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 35, Number 25 Thursday, June 27, 2019 The Beauty of Nature bbyy WWilliamilliam HHalliaralliar “The mission of Indiana State Parks is to conserve, manage and interpret our resources, while creating memorable experiences for everyone.” The beach at Indiana Dunes State Park. Much of the talk among visitors to our lakeshore The creation of the state park in Chesterton is a is of the new national park and all it has to offer. lesson in “balance, compromise and good working Perhaps an equally important story, one with an relationships between state and local governments, even longer history that for so many years impacted industry and private interests — an example of how life in Northwest Indiana, is Indiana Dunes State life should work,” says Serena Ard, Westchester Park. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore became Township History Museum curator. She is recog- a reality in 1966, gaining national park status last nized as the local authority on the history of our year. Our state park has been welcoming visitors state park, and the Prairie Club of Chicago, which since it opened in 1925. Continued on Page 2 THE Page 2 June 27, 2019 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 • FAX 219/879-8070 %HDFKHU&RPSDQ\'LUHFWRU\ e-mail: News/Articles - [email protected] 'RQDQG7RP0RQWJRPHU\ 2ZQHUV email: Classifieds - [email protected] $QGUHZ7DOODFNVRQ (GLWRU http://www.thebeacher.com/ 'UHZ:KLWH 3ULQW6DOHVPDQ PRINTE ITH Published and Printed by -DQHW%DLQHV ,QVLGH6DOHV&XVWRPHU6HUYLFH T %HFN\:LUHEDXJK 7\SHVHWWHU'HVLJQHU T A S A THE BEACHER BUSINESS PRINTERS 5DQG\.D\VHU 3UHVVPDQ 'RUD.D\VHU %LQGHU\ Delivered weekly, free of charge to Birch Tree Farms, Duneland Beach, Grand Beach, Hidden Shores, Long Beach, Michiana Shores, Michiana MI and Shoreland Hills.