INDIANA STATE PARKS and the HOOSIER IMAGINATION, 1916-1933 by STEVEN MICHAEL BURROWS DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayflies, Stoneflies, and Caddisflies of Streams and Marshes of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, USA

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 556: 43–63Mayflies, (2016) stoneflies, and caddisflies of streams and marshes of Indiana Dunes... 43 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.556.6725 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies of streams and marshes of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, USA R. Edward DeWalt1, Eric J. South2 , Desiree R. Robertson3, Joy E. Marburger4, Wendy W. Smith4, Victoria Brinson5 1 University of Illinois, Prairie Research Institute, Illinois Natural History Survey, 1816 S Oak St., Cham- paign, IL 61820 2 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Department of Entomology, 320 Morrill Hall, 505 S. Goodwin Ave, Urbana, IL 61801 3 Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605 4 Great Lakes Research and Education Center, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, 1100 N. Mineral Springs Road, Porter, Indiana 46304 5 1545 Senator Lane, Ford heights, Illinois 60411 Corresponding author: R. Edward DeWalt ([email protected]) Academic editor: R. Holzenthal | Received 30 September 2015 | Accepted 16 December 2015 | Published 21 January 2016 http://zoobank.org/442510FA-C734-4A6B-9D5C-BDA917C1D5F6 Citation: DeWalt RE, South EJ, Robertson DR, Marburger JE, Smith WW, Brinson V (2016) Mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies of streams and marshes of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, USA. ZooKeys 556: 43–63.doi: 10.3897/ zookeys.556.6725 Abstract United States National Parks have protected natural communities for one hundred years. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore (INDU) is a park unit along the southern boundary of Lake Michigan in Indiana, USA. An inventory of 19 sites, consisting of a seep, 12 streams, four marshes, a bog, and a fen were ex- amined for mayflies (Ephemeroptera), stoneflies (Plecoptera), and caddisflies (Trichoptera) (EPT taxa). -

Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE

Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE Strategic Goals: • Conserve, manage and protect existing forests, especially large forest patches, with increased emphasis on oak regeneration • Restore, expand and connect forests, especially in riparian areas • Connect people to forests, especially children and land-use decision makers, and coordinate education training and technical assistance • Maintain and expand markets for Indiana hardwoods, with special focus on secondary processors and promoting the environmental benefits of wood products to local communities and school groups • Significantly increase the size of Indiana’s urban forest canopy by developing community assistance programs and tools Indiana Forest Action Plan | 2020 Update 1 Executive Summary The 2020 Indiana Forest Action Plan is an update to the 2010 Indiana Statewide Forest Assessment and Indiana Statewide Forest Strategy. The purpose remains unchanged: to address the sustainability of Indiana’s statewide forests and develop a plan to ensure a desired future condition for forests in the state. This plan is distinct from the Indiana DNR Division of Forestry Strategic Direction 2020-2025. Indiana forest stakeholders participating in developing this Forest Action Plan maintained the broader perspective of all forest lands, public and private, and based recommendations on the roughly 5 million acres of forest in Indiana throughout the document. This document includes conditions and trends of forest resources in the state, threats to forest -

June 15-21, 2017

JUNE 15-21, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFORTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM Proudly presents in Fort Wayne, Indiana ON SALETICKETS FRIDAY ON SALE JUNE NOW! 2 ! ONTICKETS SALE FRIDAYON SALE NOW! JUNE 2 ! ONTICKETS SALE FRIDAY ON SALE NOW! JUNE 2 ! ProudlyProudly presents inpresents Fort Wayne, in Indiana Fort Wayne, Indiana 7KH0RWRU&LW\0DGPDQ5HWXUQV7R)RUW:D\QH ONON SALE SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALEON NOW! SALE NOW!ON SALE NOW! ON SALEON SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALE NOW! WEDNESDAY SEPTEMBER 20, 2017 • 7:30 PM The Foellinger Outdoor Theatre GORDON LIGHTFOOT TUESDAY AUGUST 1, 2017 • 7:30 PM 7+856'$<0$<30 7+856'$<0$<30Fort Wayne, Indiana )5,'$<0$<30THURSDAY)5,'$<0$<30 AUGUST 24,78(6'$<0$<30 2017 • 7:30 PM 78(6'$<0$<30 The Foellinger Outdoor Theatre THE FOELLINGER OUTDOOR THEATRE The Foellinger Outdoor TheatreThe Foellinger TheThe Outdoor Foellinger Foellinger Theatre Outdoor OutdoorThe Foellinger Theatre Theatre Outdoor TheatreThe Foellinger Outdoor Theatre Fort Wayne, Indiana FORT WAYNE, INDIANA Fort Wayne, Indiana Fort Wayne, IndianaFortFort Wayne, Indiana IndianaFort Wayne, Indiana Fort Wayne, Indiana ON SALE ONON NOW!SALE SALE NOW! NOW! ON SALE ON NOW! SALE ON NOW! SALE ON SALE NOW!ON NOW! SALE NOW! ONON SALE SALEON NOW! SALE NOW! NOW!ON SALE NOW!ON SALE ON SALE NOW! NOW! 14 16 TOP 40 HITS Gold and OF GRAND FUNK MORE THAN 5 Platinum TOP 10 HITS Records 30 Million 2 Records #1 HITS RAILROAD! Free Movies Sold WORLDWIDE THURSDAY AUGUST 3, 2017 • 7:30 PM Tickets The Nut Job Wed June 15 9:00 pm MEGA HITS 7+856'$<$8*867307+856'$<$8*86730On-line By PhoneTUESDAY SEPTEMBERSurly, a curmudgeon, 5, 2017 independent • 7:30 squirrel PM is banished from his “ I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home)” “ We’re An American Band” :('1(6'$<$8*86730:('1(6'$<$8*86730 “The Loco-Motion”)5,'$<-8/<30)5,'$<-8/<30 “Some Kind of Wonderful” “Bad Time” www.foellingertheatre.org (260) 427-6000 park and forced to survive in the city. -

Indiana – Land of the Indians

Indiana – Land of the Indians Key Objectives State Parks and Reservoirs Featured In this unit students will learn about American Indian tribes ■ Pokagon State Park stateparks.IN.gov/2973.htm in early Indiana and explore the causes of removal of three ■ Tippecanoe River State Park stateparks.IN.gov/2965.htm American Indian groups from Indiana, their resettlement ■ Prophetstown State Park stateparks.IN.gov/2971.htm during the 1830s, and what life is like today for these tribes. ■ Mississinewa Lake stateparks.IN.gov/2955.htm Activity: Standards: Benchmarks: Assessment Tasks: Key Concepts: Indiana Indian tribes Identify and describe historic Native American Indian removal groups who lived in Indiana before the time Be able to name the various American Home and Indiana rivers SS.4.1.2 of early European exploration, including ways Indian tribes who called Indiana home Language “Home” and what that the groups adapted to and interacted with and where in the state they lived. it means the physical environment. Indiana Indians today Explain the importance of major transporta- Identify important rivers in Indiana tion routes, including rivers, in the exploration, SS.4.3.9 and explain their value to people and settlement and growth of Indiana, and in the parks across time. state’s location as a crossroad of America. Understand that the way we write and Consult reference materials, both print and pronounce Indian words is different ELA.4.RV.2.5 digital, to find the pronunciation and clarify than how they may have originally been the precise meanings of words and phrases. spoken. Be able to describe the reasons why the American Indians were removed Identify and explain the causes of the removal and where they ended up settling, and Disruption SS.4.1.5 of Native American Indian groups in the state understand the lifeways and landscape of Tribal Life and their resettlement during the 1830s. -

Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006

The Filson Historical Society Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 For information regarding literary and copyright interest for these papers, see the Curator of Special Collections, James J. Holmberg Size of Collection: 5 Cubic Feet Location Number: Mss./BK/B396 Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 Scope and Content Note The records of the Beckham Bird Club consist of the minutes of monthly club meetings ranging from the 1935 founding through 2000. In addition, the collection includes copies of The Observer, the club’s monthly newsletter, ranging from 1968 to 2000. Collection also contains various newspaper clippings related to the club and to conservation issues; club financial records, birding and bird count records; membership records; and general club correspondence regarding programming, special events, committees, and public relations. The Beckham Bird Club was founded as the Louisville chapter of the Kentucky Ornithological Society. Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 Biographical Note The Beckham Bird Club was founded in 1935 as the Louisville chapter of the Kentucky Ornithological Society. Members of the club participate in various social and environmental activities. The Club holds monthly meetings in which guests are often invited to give lectures relevant to birds or conservation. In addition to the monthly meetings, the club participates in bird counts, holds several birding field trips each month, and plays a major role in the yearly bird census. Club members are often very active in various conservation movements in the Louisville area. For example, members have established various wildlife sanctuaries, aided in the wildlife friendly development of the waterfront, and worked to reduce pollution and increase recycling. -

Brown County State Park Fall Clean-Up by Jody Weldy

INDIANA TRAIL RIDERS PRSRT STD ASSOCIATION, INC. US POSTAGE PAID Post Office Box 185 NOBLESVILLE, IN Farmland, IN 47340 Trail Mix PERMIT NO. 21 Return Address Requested The Official Publication of the Indiana Trail Riders Association, Inc. March, 2017 ITRA GOLD NUGGET Brown County State Park Fall Clean-Up CORP By Jody Weldy For the past five years or so, it seems one of the projects at the fall cleanup over Thanksgiving weekend was helping Yvette work on the F Trail that leads to the store on SR 135. The trail going down the hill not far from the road has always been a problem. It's not a great design but we have no choice. Several years ago when the store ORATE SPONSOR changed ownership the previous owner did not want riders to ride the ITRA BRONZE NUGGET trail on his property anymore. Yvette worked hard to lease a right-a- CORPORATE SPONSOR way from another property owner. That's why the trail is where it is today. This year though, we made great progress. A volunteer brought his skid loader. With the additional help of driving and following excellent orders, they were able to remove all the mud which was every bit of a foot deep creating horrible footing for the horses. Once the mud was gone, fabric was put down. Then the ITRA TRAIL LEAD remaining rock that we had been using all the previous years was put CORPORATE SPONSOR down over the fabric although a lot more rock is needed. If anyone wants to donate a load we'll take it. -

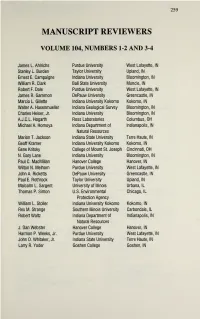

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 261 (1995) Volume 104 (3-4) P

259 MANUSCRIPT REVIEWERS VOLUME 104, NUMBERS 1-2 AND 3-4 James L. Ahlrichs Purdue University West Lafayette, IN Stanley L. Burden Taylor University Upland, IN Ernest E. Campaigne Indiana University Bloomington, IN William R. Clark Ball State University Muncie, IN Robert F. Dale Purdue University West Lafayette, IN James R. Gammon DePauw University Greencastle, IN Marcia L. Gillette Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Walter A. Hasenmueller Indiana Geological Survey Bloomington, IN Charles Heiser, Jr. Indiana University Bloomington, IN A.J.C.L. Hogarth Ross Laboratories Columbus, OH Michael A. Homoya Indiana Department of Indianapolis, IN Natural Resources Marion T. Jackson Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN Geoff Kramer Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Gene Kritsky College of Mount St. Joseph Cincinnati, OH N. Gary Lane Indiana University Bloomington, IN Paul C. MacMillan Hanover College Hanover, IN Wilton N. Melhorn Purdue University West Lafayette, IN John A. Ricketts DePauw University Greencastle, IN Paul E. Rothrock Taylor University Upland, IN Malcolm L. Sargent University of Illinois Urbana, IL Thomas P. Simon U.S. Environmental Chicago, IL Protection Agency William L. Stoller Indiana University Kokomo Kokomo, IN Rex M. Strange Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL Robert Waltz Indiana Department of Indianapolis, IN Natural Resources J. Dan Webster Hanover College Hanover, IN Harmon P. Weeks, Jr. Purdue University West Lafayette, IN John 0. Whitaker, Jr. Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN Larry R. Yoder Goshen -

Plan ID.Indd

Contents Introduction . .1 Resource Overview . 2 Natural History . 2 Cultural History . 3 Existing Conditions . .5 Audiences . 5 Facilities . 6 Staff . 7 Programs . 7 Media . 9 Partnerships . .10 Regional Offerings . .12 Interpretive Themes . .13 Recommendations . .14 Interpretive Center . 14 Pavilion . 17 Self-Guided Media . 18 Programs . 19 Staff . .20 Other Locations . 20 Summary . 22 Introduction In response to a need to stay current with interpretive and visitor trends and to maximize limited staff and fi nan- cial resources, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of State Parks and Reservoirs has devel- oped this Interpretive Master Plan for Indiana Dunes State Park. The plan accomplishes this task by: a. focusing interpretive efforts on a site-specifi c theme b. identifying needs for guided and self-guided interpretation, and c. recommending actions to fi ll those needs. The process of developing interpretive recommendations considers three components: a. Resource. What are the natural and cultural resources of the site.? b. Visitor. Who are the current users? What are the untapped audiences? c. Agency. What is the mission of the agency? What are the management goals within the agency? Other regional interpretive experiences and partnerships are incorporated to stretch staff and fi nances, foster cooperation and prevent competition. Several factors make the plan important for Indiana Dunes State Park: • In 2016, Indiana State Parks will be celebrating its 100th birthday. • The Indiana Dunes Nature Center opened int 1990. Most of the exhibits have been unchanged and are showing their age. • Indiana Dunes is unique from other parks. Recommendations need to refl ect: 1. Most of the park’s visitors are day use only. -

RELAX. REFUEL. RECHARGE. “Adopt the Pace of Nature: Her Secret Is Patience.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

RECREATION RELAX. REFUEL. RECHARGE. “Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson Young or old, you will thoroughly enjoy the many wonderful activities and places to visit, all of which offer great opportunities to relax, refuel and recharge. BASEBALL & SOFTBALL ARMSTRONG PARK: 821 Beck Ln., Lafayette LOEB STADIUM: 1915 Scott St., Columbian — 3 baseball fields. Park, Lafayette — Baseball field. CUMBERLAND PARK: 3101 N. Salisbury St., LYBOLT SPORTS PARK: 1300 Canal Rd., West Lafayette — 2 lighted softball fields, Lafayette — 3 lighted youth baseball fields. baseball field. MARLEN PARK: 5000 S. 150 E., Lafayette — FAITH COMMUNITY CENTER: 5526 Mercy Lighted softball diamond. Way, Lafayette — Softball field. MCCAW PARK: 3745 Union St., Lafayette — FAMILY SPORTS CENTER: 3242 W. 250 N., 3 lighted youth baseball fields. West Lafayette — Softball/ baseball field. MURDOCK PARK: 2100 Cason St., Lafayette — Softball field. BASKETBALL ARLINGTON PARK: 1635 Arlington Rd., MCALLISTER RECREATION CENTER: Lafayette 2351 N. 20th St., Lafayette, 765-807-1360 ARMSTRONG PARK: 821 Beck Ln., Lafayette MCCAW PARK: 3745 Union St., Lafayette CENTENNIAL PARK: 600 Brown St., Lafayette MURDOCK PARK: 2100 Cason St., Lafayette CUMBERLAND PARK: 3101 N. Salisbury St., NORTH DARBY PARK: 14 Darby Ln., Lafayette West Lafayette PARKWEST FITNESS: 1330 Win Hentschel Blvd., FAITH COMMUNITY CENTER: 5526 Mercy West Lafayette, 765-464-3435 Way, Lafayette, 765-449-4600 SHAMROCK PARK: 115 Sanford St., Lafayette FAMILY SPORTS CENTER 3242 W. 250 N., : SOUTH TIPP PARK: 300 Fountain St., Lafayette West Lafayette, 765-464-0100 TOMMY JOHNSTON PARK: 200 S. Chauncey HANNA PARK: 1201 N. 18th St., Lafayette Ave., West Lafayette LINWOOD PARK: 1500 Greenbush St., YWCA: *1950 S. -

Indiana Forest Health Highlights the Resources the Current and Future Forest Health Problems for Indiana Forests Involve Native and Exotic Insects and Diseases

2005 Indiana Forest Health Highlights The Resources The current and future forest health problems for Indiana forests involve native and exotic insects and diseases. The current forest health problem is tree mortality from the looper epidemic, forest tent caterpillar epidemic, pine bark beetles, oak wilt, Dutch Elm Disease, Ash Yellows and weather. Other impacts from these forest health problems are change in species diversity, altered wildlife habitat, growth loss and reduced timber value. What We Found Yellow-poplar is the most common species across Indiana today in terms of total live volume (fig. 1.7). Numerous other species, including ecologically and economically important hardwood species such as sugar maple, white oak, black oak, white ash, and northern red oak, contribute substantially to Indiana’s forest volume. In terms of total number of trees, sugar maple dominates, with more than twice as many trees as the next most abundant species (American elm) (fig. 1.8). Other common species include sassafras, flowering dog-wood, red maple, and black cherry. Overall, 80 individual tree species were recorded during the forest inventory. Although yellow-poplar and white oak is number one and three, respectively, in terms of total live volume across Indiana, they rank far lower in number of trees, indicating their large individual tree size compared with other species. The growing-stock volume of selected species has increased substantially since 1986, more than 100 per-cent in the case of yellow-poplar (fig. 1.9). However, black and white oak had volume increases of less than 20 percent during that period. Indiana`s forests 1999-2003 – Part A and Part B The future forest health problem is tree mortality and the other associated impacts from tree death from exotic species and the insects and diseases listed above, as they will continue to cause damage in the near future and then return again some time in the future. -

Chief Richardville House to Be Considered for National Landmark

RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED RETURN SERVICE MIAMI, OK 74355 MIAMI NATION An Official Publication of the Sovereign Miami Nation BOX 1326 P.O. STIGLER, OK 74462 PERMIT NO 49 PERMIT PAID US POSTAGE PR SRT STD PR SRT Vol. 10, No. 2 myaamionki meeloohkamike 2011 Myaamiaki Gather To Preview New Story Book By Julie Olds Myaamia citizens and guests gathered at the Ethel Miller Tribal Traditions Committee and Cultural Resources Of- Moore Cultural Education Center (longhouse) on January fice with the wonderful assistance of our dear friend Laurie 28, 2011 to herald the publication of a new book of my- Shade and her Title VI crew. aamia winter stories and traditional narratives. Following dinner it was finally story time. George Iron- “myaamia neehi peewaalia aacimoona neehi aalhsooh- strack, Assistant Director of the Myaamia Project, hosted kaana: Myaamia and Peoria Narratives and Winter Stories” the evening of myaamia storytelling. Ironstrack, joined is a work 22 years in the making and therefore a labor of by his father George Strack, opened by giving the story love to all involved, especially the editor, and translator, of where the myaamia first came from. Ironstrack gave a Dr. David Costa. number of other stories to the audience and spoke passion- Daryl Baldwin, Director of the Myaamia Project, worked ately, and knowingly, of the characters, cultural heroes, closely with Dr. Costa throughout the translation process. and landscapes intertwined to the stories. The audience Baldwin phoned me (Cultural Resources Officer Julie listened in respectful awe. Olds) in late summer of 2010 to report that Dr. Costa had To honor the closing of the “Year of Miami Women”, two completed the editing process and that the collection was women were asked to read. -

What's New at Indiana State Parks

Visit us at www.stateparks.IN.gov What’s New at Indiana State Parks in 2018 Below is a snapshot of work we have done and will do to prepare for your visits in 2018. There are many other small projects not listed that help manage and interpret the facilities, natural and cultural resources, and history of Indiana’s state park system. Indiana’s 32 state park properties have more than 2,000 buildings, 700 miles of trails, 636 hotel/lodge rooms, 17 marinas, 75 launching ramps, 17 swimming pools, 15 beaches, 7,701 campsites, more than 200 shelters, 160 or so playgrounds and 150 cabins. In recent years, we have focused attention on campground and cabin improvements, filling full-time and seasonal staff positions, and continuing a tradition of excellence in interpretation and in hospitality at Indiana State Park inns. We have a new 5-year plan, based on public responses to our Centennial Survey (more than 10,000 responses) and input from staff. It focuses on facilities and trails, improving efforts to manage our natural resources and remove invasive species, investing in technology, looking at ways to be more environmentally responsible, and training and support for park staff. Learn about our mission, vision and values at stateparks.IN.gov/6169.htm. We have wonderful partners and volunteers. Our Friends Groups and other donors contributed thousands of dollars and labor hours for projects and events. Creative and dedicated employees stretch the dollars that you pay when you enter the gate, rent a campsite, launch a boat or attend a special workshop or program.