Fort Benjamin Harrison: from Military Base to Indiana State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE

Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE Indiana Forest Action Plan 2020 UPDATE Strategic Goals: • Conserve, manage and protect existing forests, especially large forest patches, with increased emphasis on oak regeneration • Restore, expand and connect forests, especially in riparian areas • Connect people to forests, especially children and land-use decision makers, and coordinate education training and technical assistance • Maintain and expand markets for Indiana hardwoods, with special focus on secondary processors and promoting the environmental benefits of wood products to local communities and school groups • Significantly increase the size of Indiana’s urban forest canopy by developing community assistance programs and tools Indiana Forest Action Plan | 2020 Update 1 Executive Summary The 2020 Indiana Forest Action Plan is an update to the 2010 Indiana Statewide Forest Assessment and Indiana Statewide Forest Strategy. The purpose remains unchanged: to address the sustainability of Indiana’s statewide forests and develop a plan to ensure a desired future condition for forests in the state. This plan is distinct from the Indiana DNR Division of Forestry Strategic Direction 2020-2025. Indiana forest stakeholders participating in developing this Forest Action Plan maintained the broader perspective of all forest lands, public and private, and based recommendations on the roughly 5 million acres of forest in Indiana throughout the document. This document includes conditions and trends of forest resources in the state, threats to forest -

Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006

The Filson Historical Society Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 For information regarding literary and copyright interest for these papers, see the Curator of Special Collections, James J. Holmberg Size of Collection: 5 Cubic Feet Location Number: Mss./BK/B396 Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 Scope and Content Note The records of the Beckham Bird Club consist of the minutes of monthly club meetings ranging from the 1935 founding through 2000. In addition, the collection includes copies of The Observer, the club’s monthly newsletter, ranging from 1968 to 2000. Collection also contains various newspaper clippings related to the club and to conservation issues; club financial records, birding and bird count records; membership records; and general club correspondence regarding programming, special events, committees, and public relations. The Beckham Bird Club was founded as the Louisville chapter of the Kentucky Ornithological Society. Beckham Bird Club Records, 1934-2006 Biographical Note The Beckham Bird Club was founded in 1935 as the Louisville chapter of the Kentucky Ornithological Society. Members of the club participate in various social and environmental activities. The Club holds monthly meetings in which guests are often invited to give lectures relevant to birds or conservation. In addition to the monthly meetings, the club participates in bird counts, holds several birding field trips each month, and plays a major role in the yearly bird census. Club members are often very active in various conservation movements in the Louisville area. For example, members have established various wildlife sanctuaries, aided in the wildlife friendly development of the waterfront, and worked to reduce pollution and increase recycling. -

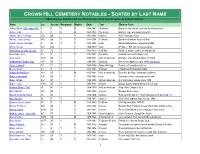

Crown Hill Cemetery Notables - Sorted by Last Name

CROWN HILL CEMETERY NOTABLES - SORTED BY LAST NAME Most of these notables are included on one of our historic tours, as indicated below. Name Lot Section Monument Marker Dates Tour Claim to Fame Achey, David (Dad, see p 440) 7 5 N N 1838-1861 Skeletons Gambler who met his “just end” when murdered Achey, John 7 5 N N 1840-1879 Skeletons Gambler who was hung for murder Adams, Alice Vonnegut 453 66 Y 1917-1958 Authors Kurt Vonnegut’s sister Adams, Justus (more) 115 36 Y Y 1841-1904 Politician Speaker of Indiana House of Rep. Allison, James (mansion) 2 23 Y Y 1872-1928 Auto Allison Engineering, co-founder of IMS Amick, George 723 235 Y 1924-1959 Auto 2nd place 1958 500, died at Daytona Armentrout, Lt. Com. George 12 12 Y 1822-1875 Civil War Naval Lt., marble anchor on monument Armstrong, John 10 5 Y Y 1811-1902 Founders Had farm across Michigan road Artis, Lionel 1525 98 Y 1895-1971 African American Manager of Lockfield Gardens 1937-69 Aufderheide’s Family, May 107 42 Y Y 1888-1972 Musician She wrote ragtime in early 1900s (her music) Ayres, Lyman S 19 11 Y Y 1824-1896 Names/Heritage Founder of department stores Bacon, Hiram 43 3 Y 1801-1881 Heritage Underground RR stop in Indpls Bagby, Robert Bruce 143 27 N 1847-1903 African American Ex-slave, principal, newspaper publisher Baker, Cannonball 150 60 Y Y 1882-1960 Auto Set many cross-country speed records Baker, Emma 822 37 Y 1885-1934 African American City’s first black female police 1918 Baker, Jason 1708 97 Y 1976-2001 Heroes Marion County Deputy killed in line of duty Baldwin, Robert “Tiny” 11 41 Y 1904-1959 African American Negro Nat’l League 1920s Ball, Randall 745 96 Y 1891-1945 Heroes Fireman died on duty Ballard, Granville Mellen 30 42 Y 1833-1926 Authors Poet, at CHC ded. -

PX Call for Offers Dec 2020.Indd

11,075 SF BUILDING FOR SALE CALL FOR OFFERS: “PX BUILDING” ORIGINAL OFFICER’S QUARTERS AT HISTORIC FORT BEN 5745 Lawton Loop East Drive The Fort Harrison Reuse Authority (FHRA) is excited to announce that the PX building is now available for sale and redevelopment for a creative reuse project that is sensitive to the historic surroundings - including offi ce, retail, restaurant or other allowed use. Located in the historical Lawton Loop district of “Fort Ben,” the PX building was originally built in 1908 as the Fort Benjamin Harrison Army Base PX (Post Exchange store) and featured a basement gymnasium for soldiers. Later, when a new PX was built, the building was converted to a non- 5745 Lawton Loop East Drive on 0.8-acres commissioned offi cers club. Today it is a brick and beam historic shell waiting for a new life. LAST OPPORTUNITY TO OWN A PIECE OF FORT BEN HISTORY! Since the base closure, the former military post has become a vibrant residential, offi ce, retail and business campus that is widely recognized as a model for reuse and redevelopment of a former military installation. Fort Ben continues to grow and is nearing its fi nal leg in its redevelopment journey - with less than 20-acres available. The PX is the fi nal historic building owned by the FHRA available for reuse. Fort Ben Campus • Tax Increment Finance (TIF) District and federal Opportunity Zone • New city center for Lawrence, IN only 20 minutes northeast of downtown Indianapolis • Walkable, green campus with abundant on-street parking central to major employee hubs • 2020 -

Medical Mobilization and the War and Later at Other Depots and Camps

the arm, or vasomotor or vasa vasorum disturbances at the government prices. Samples of cloths with the issue prices will be kept on hand by all camp, cantonment and post quartermasters and to modified nutritional conditions in the wall may be examined by officers on request after the date mentioned. For leading the present stock will be carried at the following depots only, but this of the vessel. Halsted is inclined to reject these list will be extended from time to time as cloth becomes available: New York depot, Washington depot, Atlanta depot, Sam Houston explanations. He believes that what he describes as depot, San Francisco depot, Chicago depot, St. Louis depot. the abnormal, of the blood in the 3. The quartermaster general will determine by thorough investiga¬ whirlpool-like play tion a schedule of fair prices for making uniforms, including all neces¬ relatively dead pocket just below the site of the con¬ sary trimmings, linings, etc., but not including the cloths, and prepare a list of responsible tailors who agree to make uniforms for officers striction, and the lowered pulse pressure may be the at the schedule rates, the quartermaster general guaranteeing to the chief in tailors the collection of bills for all uniforms ordered through the repre¬ factors concerned the production of the dilata¬ sentatives of the quartermaster general. The schedule of prices, the tion. The of this conclusion must be estab¬ list of tailors agreeing to make uniforms at these prices and the regula¬ validity tions governing the sale to officers of the standard cloths, the placing lished before a rational method of cure can be insti¬ of orders, the acceptance of uniforms ordered and the payment of bills will then be published to the service. -

Parks & Green Spaces Within the I-465 Ring

Parks & Green Spaces within the I-465 ring Blickman Educational Trail Park (6399 N. Meridian St.) Broad Ripple Park (1500 Broad Ripple Ave.) 62 acres Fall Creek & 30th Park (2925 E Fall Creek Pkwy N Dr.) - borders the Fall Creek Parkway Trail Franklin Township Community Park (8801 E Edgewood Ave.) Glenns Valley Nature Park (8015 Bluffs Rd.) Holliday Park (6349 Springmill Rd.) 94 acres Juan Solomon Park (6100 Grandview Dr.) 41 acres Northwestway Park (5253 W 62nd St.) Paul Ruster Park (11300 E Prospect St.) 82 acres Raymond Park (8300 Raymond St.) 35 acres Skiles Test Nature Park (6828 Fall Creek Rd.) Town Run Trail Park South (5325 E 96th St.) 127 acres - bikers have right-of-way; hike with extreme caution Washington Park (3130 E 30th St.) 128 acres Lilly ARBOR (adjacent to IUPUI campus, located along the White River on Porto Alegre St. between 10th St. bridge and New York St. bridge; park in lot 63 and take stairs at New York St. down to the trail) Parks & Green Spaces outside the I-465 ring North (Boone & Hamilton Counties) Central Park (1235 Central Park Dr. E, Carmel) 159 acres Cheeney Creek Natural Area (11030 Fishers Pointe Blvd., Fishers) 25 acres Cool Creek Park (2000 E 151st St, Carmel) 90 acres Creekside Nature Park (11001 Sycamore St., Zionsville) 18 acres - parking limited; park across the street at Lions Park and take the trail under the bridge to Creekside Creekside Corporate Park (W 106th St., Zionsville) 24 acres - links to Creekside Nature Park via bridge across Eagle Creek along S main St./Zionsville Rd Hoosier Woods -

Drive Historic Southern Indiana

HOOSIER HISTORY STATE PARKS GREEK REVIVAL ARCHITECTURE FINE RESTAURANTS NATURE TRAILS AMUSEMENT PARKS MUSEUMS CASINO GAMING CIVIL WAR SITES HISTORIC MANSIONS FESTIVALS TRADITIONS FISHING ZOOS MEMORABILIA LABYRINTHS AUTO RACING CANDLE-DIPPING RIVERS WWII SHIPS EARLY NATIVE AMERICAN SITES HYDROPLANE RACING GREENWAYS BEACHES WATER SKIING HISTORIC SETTLEMENTS CATHEDRALS PRESIDENTIAL HOMES BOTANICAL GARDENS MILITARY ARTIFACTS GERMAN HERITAGE BED & BREAKFAST PARKS & RECREATION AZALEA GARDENS WATER PARKS WINERIES CAMP SITES SCULPTURE CAFES THEATRES AMISH VILLAGES CHAMPIONSHIP GOLF COURSES BOATING CAVES & CAVERNS Drive Historic PIONEER VILLAGES COVERED WOODEN BRIDGES HISTORIC FORTS LOCAL EVENTS CANOEING SHOPPING RAILWAY RIDES & DINING HIKING TRAILS ASTRONAUT MEMORIAL WILDLIFE REFUGES HERB FARMS ONE-ROOM SCHOOLS SNOW SKIING LAKES MOUNTAIN BIKING SOAP-MAKING MILLS Southern WATERWHEELS ROMANESQUE MONASTERIES RESORTS HORSEBACK RIDING SWISS HERITAGE FULL-SERVICE SPAS VICTORIAN TOWNS SANTA CLAUS EAGLE WATCHING BENEDICTINE MONASTERIES PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S HOME WORLD-CLASS THEME PARKS UNDERGROUND RIVERS COTTON MILLS Indiana LOCK & DAM SITES SNOW BOARDING AQUARIUMS MAMMOTH SKELETONS SCENIC OVERLOOKS STEAMBOAT MUSEUM ART EXHIBITIONS CRAFT FAIRS & DEMONSTRATIONS NATIONAL FORESTS GEMSTONE MINING HERITAGE CENTERS GHOST TOURS LECTURE SERIES SWIMMING LUXURIOUS HOTELS CLIMB ROCK WALLS INDOOR KART RACING ART DECO BUILDINGS WATERFALLS ZIP LINE ADVENTURES BASKETBALL MUSEUM PICNICKING UNDERGROUND RAILROAD SITE WINE FESTIVALS Historic Southern Indiana (HSI), a heritage-based -

A Merry Prairie Holiday Tradition Continues at Conner Prairie DNR

PAGE 6 The Elwood Call-Leader, The Alexandria Times-Tribune and The Tipton County Tribune Christmas Opening Edition; Wednesday, November 25, 2020 A Merry Prairie Holiday tradition continues at Conner Prairie INDIANAPOLIS – For the of COVID-19 and protect the ornaments will be available families somewhere to cele- second year in a row, visitors health of guests and staff for purchase. However, brate safely together, can once again enjoy A Merry alike, A Merry Prairie Holiday guests can still take a ride on explained Conner Prairie Prairie Holiday while experi- has been modified in key Kringle’s Carousel – the president and CEO Norman encing Conner Prairie’s mag- ways. The Welcome Center attraction has a new home in Burns. ical festival in a new, safer will be closed except for rest- the Civil War Journey for the “Our number one priority is way. rooms, reducing the opportu- 2020 season. the health and safety of our Beginning Friday, Nov. 27 nity for guests to congregate In addition, the Winter staff, volunteers and guests,” through Sunday, Dec. 20 and indoors. Midway games, as Wonderland Stroll experi- Burns shared. “But with so on Tuesday and Wednesday, well as activities and visits at ence will be offered without many central Indiana holiday Dec. 22-23, Conner Prairie’s Mr. and Mrs. Claus’s Cabin wagon rides this year, and events and activities can- grounds will be transformed will not take place this year, guests will have the chance celled this year, we felt it was into a winter wonderland of although Selfies with Santa to explore thousands of important to still try to deliver lights and warm holiday fun. -

What's New at Indiana State Parks

Visit us at www.stateparks.IN.gov What’s New at Indiana State Parks in 2018 Below is a snapshot of work we have done and will do to prepare for your visits in 2018. There are many other small projects not listed that help manage and interpret the facilities, natural and cultural resources, and history of Indiana’s state park system. Indiana’s 32 state park properties have more than 2,000 buildings, 700 miles of trails, 636 hotel/lodge rooms, 17 marinas, 75 launching ramps, 17 swimming pools, 15 beaches, 7,701 campsites, more than 200 shelters, 160 or so playgrounds and 150 cabins. In recent years, we have focused attention on campground and cabin improvements, filling full-time and seasonal staff positions, and continuing a tradition of excellence in interpretation and in hospitality at Indiana State Park inns. We have a new 5-year plan, based on public responses to our Centennial Survey (more than 10,000 responses) and input from staff. It focuses on facilities and trails, improving efforts to manage our natural resources and remove invasive species, investing in technology, looking at ways to be more environmentally responsible, and training and support for park staff. Learn about our mission, vision and values at stateparks.IN.gov/6169.htm. We have wonderful partners and volunteers. Our Friends Groups and other donors contributed thousands of dollars and labor hours for projects and events. Creative and dedicated employees stretch the dollars that you pay when you enter the gate, rent a campsite, launch a boat or attend a special workshop or program. -

GREENING the Crossroads

GREENING the crossroads A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE VISION FOR CENTRAL INDIANA FOREWORD Central Indiana matters. It is where we work, raise our families, share our faith and welcome visitors from around the globe for world-class conventions and sporting events. It is also an area of rich biodiversity, home to freshwater mussels, neotropical migratory birds, and vibrant forests. This is our chance to work together to raise awareness about our natural assets, to protect natural areas, to improve our air and water quality, and to enhance our quality of life. We have an opportunity to connect people to nature in their own communities. Now is the time. James Wilson Heather Bacher PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR CENTRAL INDIANA LAND TRUST CENTRAL INDIANA LAND TRUST BLACK-EYED SUSANS | WAPIHANI NATURE PRESERVE, HAMILTON COUNTY GREENING THE CROSSROADS | A GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE VISION FOR CENTRAL INDIANA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 5 What is Green Infrastructure? ................................................... 6 Why is Green Infrastructure Important? .................................... 8 How is Green Infrastructure Used? ........................................... 9 Study Area: Central Indiana ..................................................... 10 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING PROCESS ......... 13 Leadership Forums ............................................................... 14 Public Input .......................................................................... 15 Network -

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick The Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn The Indianapolis Cultural Trail is having a Glick (the Trail) is an eight-mile urban bike and pedestrian measurable economic impact. pathway that serves as a linear park in the core of downtown Property values within 500 feet (approximately one block) Indianapolis. Originally conceived by Brian Payne, Presi- of the Trail have increased 148% from 2008 to 2014, an dent and CEO of the Central Indiana Community Foundation increase of $1 billion in assessed property value. (CICF), to help create and spur development in the city’s cultural districts, the Trail provides a beautiful connection for residents and visitors to safely explore downtown. Com- many businesses along Massachusetts and Virginia Avenues.The Trail Businesshas increased surveys revenue reported and part-timecustomer andtraffic full-time for cultural districts and provides a connection to the seventh via jobs have been added due to the increases in revenue and pleted in 2012, the Trail connects the now six (originally five) - tural, heritage, sports, and entertainment venue in downtown Indianapolisthe Monon Trail. as well The as Trail vibrant connects downtown every significantneighborhoods. arts, cul customers in just the first year. It also serves as the downtown hub for the central Indiana expenditure for all users is $53, and for users from outside greenway system. theUsers Indianapolis are spending area while the averageon the Trail. exceeds The $100.average In all,expected Trail users contributed millions of dollars in local spending. -

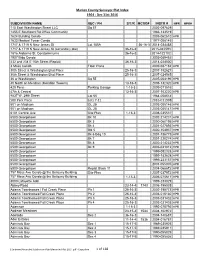

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave