Combating Opioid-Induced Constipation: New and Emerging Therapies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELISTOR, INN: Methylnaltrexone Bromide

The European Medicines Agency Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use EMEA/CHMP/10906/2008 ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RELISTOR International Nonproprietary Name: METHYLNALTREXONE BROMIDE Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/870 Assessment Report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 74 18 8613 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROCEDURE......................................... 3 1.1 Submission of the dossier ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................................... 3 2 SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSION............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Quality aspects....................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Non-clinical aspects............................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Clinical aspects .................................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Pharmacovigilance...............................................................................................................41 -

Albany-Molecular-Research-Regulatory

PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF A Abiraterone Malta • Benztropine Mesylate Cedarburg • Adenosine Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • * Betaine Citrate Anhydrous Bon Encontre • Betametasone-17,21- Alcaftadine Spain Spain • • Dipropionate Sterile • Alclometasone-17, 21- Spain Betamethasone Acetate Spain Dipropionate • • Altrenogest Spain • • Betamethasone Base Spain Amphetamine Aspartate Rensselaer Betamethasone Benzoate Spain * Monohydrate Milled • Betamethasone Valerate Amphetamine Sulfate Rensselaer Spain * • Acetate Betamethasone-17,21- Argatroban Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • • Dipropionate • • • Atenolol India • • Betamethasone-17-Valerate Spain • • Betamethasone-21- Atracurium Besylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • Phosphate Disodium Salt • • Bromfenac Monosodium Atropine Sulfate Cedarburg Lodi * • Salt Sesquihydrate • • Azanidazole Lodi Bromocriptine Mesylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • • • • Azelastine HCl Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • Budesonide Spain • • Aztreonam Rozzano - Valle Ambrosia • • Budesonide Sterile Spain • • B Bamifylline HCl Bon Encontre • Butorphanol Tartrate Cedarburg • Beclomethasone-17, 21- Spain Capecitabine Lodi Dipropionate • C • 2 *Please contact our Accounts Managers in case you are interested in this API. 3 PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF Dexamethasone-17,21- Carbimazole Bon Encontre Spain • Dipropionate -

204760Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 204760Orig1s000 OTHER REVIEW(S) MEMORANDUM DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH DATE: September 16, 2014 FROM: Julie Beitz, MD SUBJECT: Approval Action TO: NDA 204760 Movantik (naloxegol) tablets AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP Summary Naloxegol is an antagonist of opioid binding at the muͲopioid receptor. When administered at the recommended dose levels, naloxegol functions as a peripherallyͲacting opioid receptor antagonist in tissues such as the gastrointestinal tract, thereby decreasing the constipating effects of opioids. Naloxegol is a PEGylated derivative of naloxone and a new molecular entity. Pegylation confers the following properties: naloxegol has reduced passive permeability across membranes compared to naloxone; naloxegol is a PͲglycoprotein (PͲgp) efflux transporter substrate; and naloxegol is orally bioavailable. The reduced passive permeability and PͲgp efflux transporter properties limit CNS entry of naloxegol compared to naloxone. This memo documents my concurrence with the Division of Gastroenterology and Inborn Errors Product’s recommendation for approval of NDA 204760 for Movantik (naloxegol) tablets for the treatment of opioidͲinduced constipation (OIC) in adult patients with chronic nonͲcancer pain. Discussions regarding product labeling, and postmarketing study requirements and commitments have been satisfactorily completed. There are no inspectional issues that preclude approval. Dosing The recommended dose of Movantik (naloxegol) tablets is 25 mg taken once daily in the morning on an empty stomach. Patients who do not tolerate this dose, may reduce the dose to 12.5 mg once daily. Maintenance laxatives should be discontinued prior to initiation of therapy with Movantik. -

Design and Synthesis of Cyclic Analogs of the Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonist Arodyn

Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn By © 2018 Solomon Aguta Gisemba Submitted to the graduate degree program in Medicinal Chemistry and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Dr. Michael Rafferty Dr. Teruna Siahaan Dr. Thomas Tolbert Date Defended: 18 April 2018 The dissertation committee for Solomon Aguta Gisemba certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Date Approved: 10 June 2018 ii Abstract Opioid receptors are important therapeutic targets for mood disorders and pain. Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonists have recently shown potential for treating drug addiction and 1,2,3 4 8 depression. Arodyn (Ac[Phe ,Arg ,D-Ala ]Dyn A(1-11)-NH2), an acetylated dynorphin A (Dyn A) analog, has demonstrated potent and selective KOR antagonism, but can be rapidly metabolized by proteases. Cyclization of arodyn could enhance metabolic stability and potentially stabilize the bioactive conformation to give potent and selective analogs. Accordingly, novel cyclization strategies utilizing ring closing metathesis (RCM) were pursued. However, side reactions involving olefin isomerization of O-allyl groups limited the scope of the RCM reactions, and their use to explore structure-activity relationships of aromatic residues. Here we developed synthetic methodology in a model dipeptide study to facilitate RCM involving Tyr(All) residues. Optimized conditions that included microwave heating and the use of isomerization suppressants were applied to the synthesis of cyclic arodyn analogs. -

Opioids in Palliative Care: Evidence Update May 2014

Opioids in palliative care Evidence Update May 2014 A summary of selected new evidence relevant to NICE clinical guideline 140 ‘Opioids in palliative care: safe and effective prescribing of strong opioids for pain in palliative care of adults’ (2012) Evidence Update 58 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Key points .................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Commentary on new evidence .......................................................................................... 5 1.1 Communication .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Starting strong opioids – titrating the dose ................................................................ 5 1.3 First-line maintenance treatment ............................................................................... 6 1.4 First-line treatment if oral opioids are not suitable – transdermal patches ................ 6 1.5 First-line treatment if oral opioids are not suitable – subcutaneous delivery ............. 7 1.6 First-line treatment for breakthrough pain in patients who can take oral opioids ...... 7 1.7 Management of constipation ..................................................................................... 8 1.8 Management of nausea .......................................................................................... -

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions Jacqueline Cleary, PharmD, BCACP Assistant Professor Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Adjunct Professor SAGE College of Nursing DISCLOSURES • Kaleo • Remitigate, LLC OBJECTIVES • Compare and contrast unique pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of chronic pain including: methadone, buprenoprhine, tapentadol, and tramadol • Select methadone, buprenorphine, tapentadol, or tramadol based on patient specific factors • Apply appropriate opioid conversion strategies to unique opioids • Understand opioid overdose risk surrounding opioid conversions and the use of unique opioids UNIQUE OPIOIDS METHADONE, BUPRENORPHINE, TRAMADOL, TAPENTADOL METHADONE My favorite drug because….? METHADONE- INDICATIONS • FDA labeled indications – (1) chronic pain (2) detoxification Oral soluble tablets for suspension NOT indicated for chronic pain treatment • Initial inpatient detoxification of opioids by a licensed trained provider with methadone and supportive care is appropriate • Methadone maintenance provider must have special credentialing and training as required by state Outpatient prescription must be for pain ONLY and say “for pain” on RX • Continuation of methadone maintenance from outside provider while patient is inpatient for another condition is appropriate http://cdn.atforum.com/wp-content/uploads/SAMHSA-2015-Guidelines-for-OTPs.pdf MECHANISM OF ACTION • Potent µ-opioid agonist • NMDA receptor antagonist • Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor • Serotonin reuptake inhibitor ADVERSE EVENTS -

Methylnaltrexone Nonf

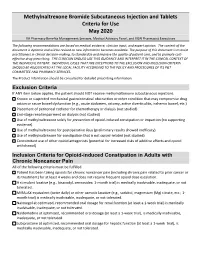

Methylnaltrexone Bromide Subcutaneous Injection and Tablets Criteria for Use May 2020 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The following recommendations are based on medical evidence, clinician input, and expert opinion. The content of the document is dynamic and will be revised as new information becomes available. The purpose of this document is to assist practitioners in clinical decision-making, to standardize and improve the quality of patient care, and to promote cost- effective drug prescribing. THE CLINICIAN SHOULD USE THIS GUIDANCE AND INTERPRET IT IN THE CLINICAL CONTEXT OF THE INDIVIDUAL PATIENT. INDIVIDUAL CASES THAT ARE EXCEPTIONS TO THE EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION CRITERIA SHOULD BE ADJUDICATED AT THE LOCAL FACILITY ACCORDING TO THE POLICY AND PROCEDURES OF ITS P&T COMMITTEE AND PHARMACY SERVICES. The Product Information should be consulted for detailed prescribing information. Exclusion Criteria If ANY item below applies, the patient should NOT receive methylnaltrexone subcutaneous injections. Known or suspected mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction or other condition that may compromise drug action or cause bowel dysfunction (e.g., acute abdomen, ostomy, active diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, etc.) Placement of peritoneal catheter for chemotherapy or dialysis (not studied) End-stage renal impairment on dialysis (not studied) Use of methylnaltrexone solely for prevention of opioid-induced constipation or impaction (no supporting evidence). Use of methylnaltrexone for postoperative ileus (preliminary results showed inefficacy). Use of methylnaltrexone for constipation that is not opioid-related (not studied) Concomitant use of other opioid antagonists (potential for increased risks of additive effects and opioid withdrawal) Inclusion Criteria for Opioid-induced Constipation in Adults with Chronic Noncancer Pain All of the following criteria must be fulfilled. -

Therapeutic Class Overview Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Constipation Agents

Therapeutic Class Overview Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Constipation Agents INTRODUCTION Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a gastrointestinal disorder that most commonly manifests as chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits in the absence of any organic disorder (Wald 2017). IBS may consist of diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), constipation-predominant (IBS-C), IBS with a mixed symptomatology (IBS-M), or unclassified IBS (IBS-U). Switching between the subtypes of IBS is also possible (Ford et al 2014). IBS is a functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by abdominal pain, discomfort, and bloating, as well as disturbed bowel habit. The exact pathogenesis of the disorder is unknown; however, it is believed that altered gastrointestinal tract motility, visceral hypersensitivity, autonomic dysfunction, and psychological factors indicate disturbances within the enteric nervous system, which controls the gastrointestinal system (Andresen et al 2008, Ford et al 2009). Prevalence estimates of IBS range from 5 to 15%, and it typically occurs in young adulthood (Ford et al 2014). IBS-D is more common in men, and IBS-C is more common in women (World Gastroenterology Organization [WGO], 2015). Symptoms of IBS often interfere with daily life and social functioning (WGO 2015). The general goals of therapy are to alleviate the patient’s symptoms and to target any specific exacerbating factors (eg, medications, dietary changes), concerns about serious illness, stressors, or potential psychiatric comorbidities that may exist (Wald 2015). Non-pharmacological interventions to combat IBS symptoms include dietary modifications such as exclusion of gas- producing foods (eg, beans, prunes, Brussel sprouts, bagels, etc.), trials of gluten avoidance, and consumption of probiotics, as well as psychosocial therapies (eg, hypnosis, biofeedback, etc.) (Ford et al 2014). -

208854Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 208854Orig1s000 SUMMARY REVIEW OND=Office of New Drugs OPQ=Office of Pharmaceutical Quality OPDP=Office of Prescription Drug Promotion OSI=Office of Scientific Investigations CDTL=Cross-Discipline Team Leader COA=Clinical Outcome Assessment CSS=Controlled Substance Staff DAAAP= Division of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Addiction Products OSE= Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology DEPI= Division of Epidemiology DMEPA=Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis DPMH = Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health MHT=Maternal Health Team Quality Review Team DISCIPLINE REVIEWER BRANCH/DIVISION Drug Substance Joseph Leginus CDER/OPQ/ONDP/ DNDAPI/NDBII Drug Product Sarah Ibrahim CDER/OPQ/ONDP/ DNDPII/NDPBV Process Zhao Wang CDER/OPQ/OPF/ DPAI/PABI Microbiology Zhao Wang CDER/OPQ/OPF/ DPAI/PABI Facility Donald Lech CDER/OPQ/OPF/DIA/IABIII Biopharmaceutics Peng Duan CDER/OPQ/ONDP/ DB/BBII Regulatory Business Cheronda Cherry-France CDER/OND/ODEIII/ DGIEP Process Manager Application Technical Lead Hitesh Shroff CDER/OPQ/ONDP/ DNDPII/NDPBV Laboratory (OTR) N/A N/A ORA Lead Paul Perdue Jr. ORA/OO/OMPTO/ DMPTPO/MDTP Environmental Analysis James Laurenson CDER/OPQ/ONDP (EA) 2 Reference ID: 4073992 1. Benefit-Risk Assessment I concur with the reviewers’ conclusions that the benefit/risk of naldemedine is favorable in the population for which this product will be approved and that the risks can be managed with labeling. The applicant proposed the following indication for naldemedine, an orally administered peripheral mu opioid receptor antagonist: Symproic is indicated for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation (OIC) in adult patients with chronic non-cancer pain. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0245287 A1 Holaday Et Al

US 20110245287A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0245287 A1 Holaday et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 6, 2011 (54) HYBRD OPOD COMPOUNDS AND Publication Classification COMPOSITIONS (51) Int. Cl. A6II 3/4748 (2006.01) C07D 489/02 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: John W. Holaday, Bethesda, MD A6IP 25/04 (2006.01) (US); Philip Magistro, Randolph, (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................... 514/282:546/45 NJ (US) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed are hybrid opioid compounds, mixed opioid salts, (21) Appl. No.: 13/024,298 compositions comprising the hybrid opioid compounds and mixed opioid salts, and methods of use thereof. More particu larly, in one aspect the hybrid opioid compound includes at (22) Filed: Feb. 9, 2011 least two opioid compounds that are covalently bonded to a linker moiety. In another aspect, the hybrid opioid compound relates to mixed opioid salts comprising at least two different Related U.S. Application Data opioid compounds or an opioid compound and a different active agent. Also disclosed are pharmaceutical composi (60) Provisional application No. 61/302,657, filed on Feb. tions, as well as to methods of treating pain in humans using 9, 2010. the hybrid compounds and mixed opioid salts. Patent Application Publication Oct. 6, 2011 Sheet 1 of 3 US 2011/0245287 A1 Oral antinociception of morphine, oxycodone and prodrug combinations in CD1 mice s Tigkg -- Morphine (2.80 mg/kg (1.95 - 4.02, 30' peak time -- (Oxycodone (1.93 mg/kg (1.33 - 2,65)) 30 peak time -- Oxy. Mor (1:1) (4.84 mg/kg (3.60 - 8.50) 60 peak tire --MLN 2-3 peak, effect at a hors 24% with closes at 2.5 art to rigg - D - MLN 2-45 (6.60 mg/kg (5.12 - 8.51)} 60 peak time Figure 1. -

Pain Management & Palliative Care

Guidelines on Pain Management & Palliative Care A. Paez Borda (chair), F. Charnay-Sonnek, V. Fonteyne, E.G. Papaioannou © European Association of Urology 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Guideline 6 1.2 Methodology 6 1.3 Publication history 6 1.4 Acknowledgements 6 1.5 Level of evidence and grade of guideline recommendations* 6 1.6 References 7 2. BACKGROUND 7 2.1 Definition of pain 7 2.2 Pain evaluation and measurement 7 2.2.1 Pain evaluation 7 2.2.2 Assessing pain intensity and quality of life (QoL) 8 2.3 References 9 3. CANCER PAIN MANAGEMENT (GENERAL) 10 3.1 Classification of cancer pain 10 3.2 General principles of cancer pain management 10 3.3 Non-pharmacological therapies 11 3.3.1 Surgery 11 3.3.2 Radionuclides 11 3.3.2.1 Clinical background 11 3.3.2.2 Radiopharmaceuticals 11 3.3.3 Radiotherapy for metastatic bone pain 13 3.3.3.1 Clinical background 13 3.3.3.2 Radiotherapy scheme 13 3.3.3.3 Spinal cord compression 13 3.3.3.4 Pathological fractures 14 3.3.3.5 Side effects 14 3.3.4 Psychological and adjunctive therapy 14 3.3.4.1 Psychological therapies 14 3.3.4.2 Adjunctive therapy 14 3.4 Pharmacotherapy 15 3.4.1 Chemotherapy 15 3.4.2 Bisphosphonates 15 3.4.2.1 Mechanisms of action 15 3.4.2.2 Effects and side effects 15 3.4.3 Denosumab 16 3.4.4 Systemic analgesic pharmacotherapy - the analgesic ladder 16 3.4.4.1 Non-opioid analgesics 17 3.4.4.2 Opioid analgesics 17 3.4.5 Treatment of neuropathic pain 21 3.4.5.1 Antidepressants 21 3.4.5.2 Anticonvulsant medication 21 3.4.5.3 Local analgesics 22 3.4.5.4 NMDA receptor antagonists 22 3.4.5.5 Other drug treatments 23 3.4.5.6 Invasive analgesic techniques 23 3.4.6 Breakthrough cancer pain 24 3.5 Quality of life (QoL) 25 3.6 Conclusions 26 3.7 References 26 4. -

WO 2012/109445 Al 16 August 2012 (16.08.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/109445 Al 16 August 2012 (16.08.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/485 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (21) International Application Number: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, PCT/US20 12/024482 DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (22) International Filing Date: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, ' February 2012 (09.02.2012) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, (26) Publication Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 13/024,298 9 February 201 1 (09.02.201 1) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): QRX- GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, PHARMA LTD.