Mechanism: a Visual, Lexical, and Conceptual History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dioscorides De Materia Medica Pdf

Dioscorides de materia medica pdf Continue Herbal written in Greek Discorides in the first century This article is about the book Dioscorides. For body medical knowledge, see Materia Medica. De materia medica Cover of an early printed version of De materia medica. Lyon, 1554AuthorPediaus Dioscorides Strange plants RomeSubjectMedicinal, DrugsPublication date50-70 (50-70)Pages5 volumesTextDe materia medica in Wikisource De materia medica (Latin name for Greek work Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hul's iatrik's, both means about medical material) is a pharmacopeia of medicinal plants and medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until it supplanted the revised herbs during the Renaissance, making it one of the longest of all natural history books. The paper describes many drugs that are known to be effective, including aconite, aloe, coloxinth, colocum, genban, opium and squirt. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and minerals, and about 1000 medicines of them. De materia medica was distributed as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic throughout the media period. From the sixteenth century, the text of the Dioscopide was translated into Italian, German, Spanish and French, and in 1655 into English. It formed the basis of herbs in these languages by such people as Leonhart Fuchs, Valery Cordus, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Klusius, John Gerard and William Turner. Gradually these herbs included more and more direct observations, complementing and eventually displacing the classic text. -

"You Can't Make a Monkey out of Us": Galen and Genetics Versus Darwin

"You can't make a monkey out of us": Galen and genetics versus Darwin Diamandopoulos A. and Goudas P. Summary The views on the biological relationship between human and ape are polarized. O n e end is summarized by the axiom that "mon is the third chimpanzee", a thesis put forward in an indirect way initially by Charles Darwin in the 19 th century.The other is a very modern concept that although similar, the human and ape genomes are distinctly different. We have compared these t w o views on the subject w i t h the stance of the ancient medical w r i t e r Galen.There is a striking resemblance between current and ancient opinion on three key issues. Firstly, on the fact that man and apes are similar but not identical. Secondly, on the influence of such debates on fields much wider than biology.And finally, on the comparative usefulness of apes as a substitute for human anatomy and physiology studies. Resume Les points de vue concernant les liens biologiques existants entre etre humain et singe sont polarises selon une seule direction. A I'extreme, on pourrait resumer ce point de vue par I'axiome selon lequel « I'homme est le troisieme chimpanze ». Cette these fut indirectement soutenue par Charles Darwin, au I9eme siecle. L'autre point de vue est un concept tres moderne soutenant la similitude mais non I'identite entre les genomes de I'homme et du singe. Nous avons compare ces deux points de vue sur le sujet en mentionnant celui du medecin ecrivain Galien, dans I'Antiquite. -

Marie François Xavier Bichat (11.11.1771 Thoirette (Dep

36 Please take notice of: (c)Beneke. Don't quote without permission. Marie François Xavier Bichat (11.11.1771 Thoirette (Dep. Jura) - 22.7.1802 Paris) Mitbegründer der experimentellen Physiologie Klaus Beneke Institut für Anorganische Chemie der Christian-Albrechts-Universität der Universität D-24098 Kiel [email protected] Auszug und ergänzter Artikel (Januar 2004) aus: Klaus Beneke Biographien und wissenschaftliche Lebensläufe von Kolloid- wissenschaftlern, deren Lebensdaten mit 1996 in Verbindung stehen. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Kolloidwissenschaften, VIIi Mitteilungen der Kolloid-Gesellschaft, 1999, Seite 37-40 Verlag Reinhard Knof, Nehmten ISBN 3-934413-01-3 37 Marie François Xavier Bichat (11.11.1771 Thoirette (Dep. Jura) - 22.7.1802 Paris) Marie François Xavier Bichat wurde als Sohn des Physikers und Arztes Jean-Baptiste Bichat und dessen Ehefrau Jeanne-Rose Bi- chard, einer Cousine ihres Mannes geboren. Dieser hatte in Montpellier studiert und prakti- zierte als Arzt in Poncin-en-Bugey. M. F. X. Bichat studierte Medizin in Montpellier und Lyon. Allerdings wurde das Studium durch die Ereignisse der Französischen Revolution öfters unterbrochen. Von 1791 bis 1793 studierte Bi- chat als Schüler von Marc-Antoine Petit (03.09.1766 Lyon - 07.07.1811 Villeurbanne) am Hôtel-Dieu in Lyon Chirugie und Anatomie. Danach ging er nach Paris, wo er von dem Chi- rugen Pierre Joseph Desault (06.02.1744 Magny-Vernois - 01.06.1795 Paris) besonders gefördert wurde und dieser ihn mit der Leitung Marie François Xavier Bichat des „Journal de Chirugie“ betraute. Pierre Desault wurde 1795, kurz vor seinem Tode, Professor an der ersten von ihm begründeten chirugischen Klinik in Frankreich, nachdem er ab 1788 als Chefchirug am Hôtel-Dieu in Paris wirkte. -

The Order of the Prophets: Series in Early French Social Science and Socialism

Hist. Sci., xlviii (2010) THE ORDER OF THE PROPHETS: SERIES IN EARLY FRENCH SOCIAL SCIENCE AND SOCIALISM John Tresch University of Pennsylvania Everything that can be thought by the mind or perceived by the senses is necessarily a series.1 According to the editors of an influential text in the history of social science, “in the first half of the nineteenth century the expression series seemed destined to a great philosophical future”.2 The expression itself seems to encourage speculation on destiny. Elements laid out in a temporal sequence ask to be continued through the addition of subsequent terms. “Series” were particularly prominent in the French Restoration and July Monarchy (1815–48) in works announcing a new social science. For example, the physician and republican conspirator J. P. B. Buchez, a former fol- lower of Henri de Saint-Simon who led a movement of Catholic social reform, made “series” central to his Introduction à la science de l’histoire. Mathematical series show a “progression”, not “a simple succession of unrelated numbers”; in human history, we discover two simultaneous series: “one growing, that of good; one diminishing, that of evil.” The inevitability of positive progress was confirmed by recent findings in physiology, zoology and geology. Correlations between the developmental stages of organisms, species, and the Earth were proof that humanity’s presence in the world “was no accident”, and that “labour, devotion and sacrifice” were part of the “universal order”. The “great law of progress” pointed toward a socialist republic in fulfilment both of scripture and of the promise of 1789. -

Aimé Bonpland (1773-1858)

Julio Rafael Contreras Roqué, Adrián Giacchino, Bárbara Gasparri y Yolanda E. Davies ENSAYOS SOBRE AIMÉ BONPLAND (1773-1858) BONPLAND Y EL PARAGUAY, EL BOTÁNICO Y SU RELACIONAMIENTO HUMANO Y UN ENIGMÁTICO VISITANTE ENSAYOS SOBRE AIMÉ BONPLAND (1773-1858) BONPLAND Y EL PARAGUAY, EL BOTÁNICO Y SU RELACIONAMIENTO HUMANO Y UN ENIGMÁTICO VISITANTE ENSAYOS SOBRE AIMÉ BONPLAND (1773-1858) BONPLAND Y EL PARAGUAY, EL BOTÁNICO Y SU RELACIONAMIENTO HUMANO Y UN ENIGMÁTICO VISITANTE Diseño gráfico: Mariano Masariche. Ilustración de tapa: Aimé Bonpland. Acero grabado. Alemania siglo XIX. Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara Centro de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas Universidad Maimónides Hidalgo 775 P. 7º - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (54) 11-4905-1100 int. 1228 / www.fundacionazara.org.ar Impreso en Argentina - 2020 Se ha hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723. No se permite la reproducción parcial o total, el almacenamiento, el alquiler, la transmisión o la transformación de este libro, en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea electrónico o mecánico, mediante fotocopias, digitalización u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y escrito del editor. Su infracción está penada por las leyes 11.723 y 25.446. El contenido de este libro es responsabilidad de sus autores Aimé Bonpland, 1773-1858 : Bonpland y el Paraguay, el botánico y su relacionamiento humano y un enigmático visitante / Julio Rafael Contreras Roqué ... [et al.]. - 1a ed . - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara ; Universidad Maimónides, 2020. 214 p. ; 24 x 17 cm. ISBN 978-987-3781-48-3 1. Biografías. I. Contreras Roqué, Julio Rafael CDD 920 Fecha de catalogación: abril de 2020 ENSAYOS SOBRE AIMÉ BONPLAND (1773-1858) BONPLAND Y EL PARAGUAY, EL BOTÁNICO Y SU RELACIONAMIENTO HUMANO Y UN ENIGMÁTICO VISITANTE AUTORES Julio Rafael Contreras Roqué(†) Adrián Giacchino1 Bárbara Gasparri1 Yolanda E. -

The Strange Case of 19Th Century Vitalism

The Strange Case of 19th Century Vitalism El extraño caso del vitalismo del siglo XIX Axel PÉREZ TRUJILLO Universidad Autónoma de Madrid [email protected] Recibido: 15/09/2011 Aprobado: 20/12/2011 Abstract: The progress of the Natural Sciences at the dawn of the 19th century was decisive in the me- taphysical debates between philosophers, as well as in literary circles around Europe. Driven by the breakthroughs in Biology, Chemistry, and Physiology, Medicine became an essential source of influence in philosophical research. The purpose of this paper is twofold: on the one hand, it will attempt to demonstrate the influence that Medicine had on the arguments advanced by a central philosopher during the 1800s, Arthur Schopenhauer, and, on the other hand, it will also trace such influence within Gothic fiction. The result will be a sober witness to the interdisciplinary nature of Philosophy, Medicine, and Literature. Keywords: Medicine, Arthur Schopenhauer, Xavier Bichat, Mary Shelley, pessimism, physio- logy, vitalism, Gothic fiction. Resumen: El avance de las Ciencias Naturales durante los primeros años del siglo XIX fue decisivo en el desarrollo de los debates metafísicos entre filósofos y, a su vez, inspiró los temas de muchas tertu- lias literarias en Europa. Impulsada por los descubrimientos en Biología, Química y Fisiología, la BAJO PALABRA. Revista de Filosofía. 63 II Época, Nº 7, (2012): 63-71 The Strange Case of 19th Century Vitalism Medicina se convirtió en una fuente de inspiración en las investigaciones filosóficas de la época. El propósito de este artículo es demostrar el impacto que la Medicina tuvo sobre los argumentos de uno de los filósofos centrales de la época, Arthur Schopenhauer. -

The Homoeomerous Parts and Their Replacement by Bichat'stissues

Medical Historm, 1994, 38: 444-458. THE HOMOEOMEROUS PARTS AND THEIR REPLACEMENT BY BICHAT'S TISSUES by JOHN M. FORRESTER * Bichat (1801) developed a set of twenty-one distinguishable tissues into which the whole human body could be divided. ' This paper seeks to distinguish his set from its predecessor, the Homoeomerous Parts of the body, and to trace the transition from the one to the other. The earlier comparable set of distinguishable components of the body was the Homoeomerous Parts, a system founded according to Aristotle by Anaxagoras (about 500-428 BC),2 and covering not just the human body, or living bodies generally, as Bichat's tissues did, but the whole material world. "Empedocles says that fire and earth and the related bodies are elementary bodies of which all things are composed; but this Anaxagoras denies. His elements are the homoeomerous things (having parts like each other and like the whole of which they are parts), viz. flesh, bone and the like." A principal characteristic of a Homoeomerous Part is that it is indefinitely divisible without changing its properties; it can be chopped up very finely to divide it, but is not otherwise changed in the process. The parts are like each other and like the whole Part, but not actually identical. Limbs, in contrast, obviously do not qualify; they cannot be chopped into littler limbs. Aristotle starts his own explanation with the example of minerals: "By homoeomerous bodies I mean, for example, metallic substances (e.g. bronze, gold, silver, tin, iron, stone and similar materials and their by-products) ...;'3 and then goes on to biological materials: "and animal and vegetable tissues (e.g. -

Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen's Philosophical Speculation Became

Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 1 January 2013 Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions Paul Anthony Abilene Christian University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/conversations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Paul (2013) "Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions," Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/conversations/vol1/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. Conversations Vol. 1 No. 1 May 2013 Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions Paul A. Anthony Abilene Christian University Graduate School of Theology, History and Theology Abstract Augustine of Hippo may never have heard of Galen of Pergamum. Three centuries separated the two, as did an almost impassable geographic and cultural divide that kept the works of Galen and other Greek writers virtually unknown in the Latin west for a millennium. Yet Galenic assumptions about human sexuality and the materiality of the soul underlie Augustine’s signature doctrine of original sin. Galen’s influence was so widely felt in the Greek-speaking east that Christians almost immediately worked his assumptions into their own theologies. -

The Ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Galen on the Elderly

2017;65:325-328 REVIEW The ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Galen on the elderly A. Diamandopoulos EKPA, Louros Foundation, Greece For the sake of brevity, we will deal here with a very small fraction of the texts of ancient Greek writers on Old Age, in a period of roughly 600 years between the 5th century BC and the 2nd century AD. And geographically also, the area covered is but a negligent fraction of the globe. Aim. To comment on a very small fraction of the texts of ancient Greek writers on Old Age, in a period of roughly 600 years between the 5th century BC and the 2nd century AD. Materials and methods. We used extracts from the writings of Plato (The Republic), Aristotle (De Anima), Plutarch (Vitae Parallelae, Moralia) and Galen (De Marcore Liber). Results. Plato presents two sides of the stance of elderly, i.e. continuity (to continue to do what they were doing in their active years), and disengagement (describes the tendency after some age to go away from your previous straggles and to contemplate on the eternal values of spirituality). Aristotle explains why in old age death is painless, like the shutting out of a tiny feeble flame. Plutarch elaborates extensively on the need to accumulate physical and mental qualifications when we are young so that we can be able to consume them later, in our old age. He declares that “although old age has much to be shameful of, at least let us not to add the disgrace of wickedness”. Finally, the social role of each person shall not mutate with age. -

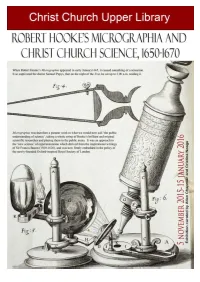

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

XAVIER BIGHAT: and Medicine Makes No Clear and Undoubted Progress-That in Has a Literature the Name- HIS LIFE and LABOURS

393 They are greatly under the influence of emotion, and off wrote and laboured, was disjointed, fragmentary, and all but sympathetic or synergic action through the spinal centre. We3worthless. to the of To the vast of have only observe effect of derangement the stomach,, appreciate justly merits this profound genius, on we is its or of eroded viscera, the action of the heart, the skin, &c., , must consider first-What anatomy and what object? in connexion with experiment, to arrive at this conclusion. How it stood before the times of Bichat, and how since? What The experiments to which I allude are the following:-Let; were and what are the views which the public, as well as the the head be removed in a frog, the spinal marrow remaining, professional mind, had adopted in respect of it? Let us care- and the circulation be ready to fail: if we now crush the fully distinguish the philosophical from the practical, the stomach or a limb with a hammer, the action of the heart. theoretical from the empirical, true generalization from mere ceases. Let the conditions be the same in another frog, with. truism. But first, of the man himself. the addition that the spinal marrow is also removed: in this! Marie Francois Xavier Bichat was born in 1771, at Thoirette, case, no influence is perceived, on crushing a limb or the in Bresse, now called the department of the Jura. His father stomach, on the action of the heart. Now, the difference is was a physician and mayor of Poncin, in Bugez; but he had * the presence or absence of the spinal centre. -

Where Did Ideas About Medieval Medicine Come From?

Where did ideas about Medieval medicine come from? What can we learn about pre-medieval medicine from the images? a) Stone Age people could successfully perform operations. b) People in the Indus Valley understood something about hygiene and tried to keep places clean (and built ways of doing it). c) (& f) Ancient Egyptians and later, Arabs, attempted to treat illness & disease and had specially ‘trained’ people to do so. d) Ancient Greeks had places of healing. e) Romans understood the importance of having clean water (and went to great lengths to make sure people had access to it). *Asclepion = a temple dedicated to the God of healing, Asclepious. Where did medieval ideas about health come from? Two men, perhaps more than any others, contributed to the Western view of medicine and health at this time. They were Hippocrates and Galen. The theory of the Four Humours Hippocrates wrote: 'The human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with others.' It was believed that the body had four humours (fluids in our bodies) and if these became unbalanced you got ill. Doctors studied a patient’s urine to detect if there was any unbalance.