Where Did Ideas About Medieval Medicine Come From?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dioscorides De Materia Medica Pdf

Dioscorides de materia medica pdf Continue Herbal written in Greek Discorides in the first century This article is about the book Dioscorides. For body medical knowledge, see Materia Medica. De materia medica Cover of an early printed version of De materia medica. Lyon, 1554AuthorPediaus Dioscorides Strange plants RomeSubjectMedicinal, DrugsPublication date50-70 (50-70)Pages5 volumesTextDe materia medica in Wikisource De materia medica (Latin name for Greek work Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hul's iatrik's, both means about medical material) is a pharmacopeia of medicinal plants and medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until it supplanted the revised herbs during the Renaissance, making it one of the longest of all natural history books. The paper describes many drugs that are known to be effective, including aconite, aloe, coloxinth, colocum, genban, opium and squirt. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and minerals, and about 1000 medicines of them. De materia medica was distributed as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic throughout the media period. From the sixteenth century, the text of the Dioscopide was translated into Italian, German, Spanish and French, and in 1655 into English. It formed the basis of herbs in these languages by such people as Leonhart Fuchs, Valery Cordus, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Klusius, John Gerard and William Turner. Gradually these herbs included more and more direct observations, complementing and eventually displacing the classic text. -

"You Can't Make a Monkey out of Us": Galen and Genetics Versus Darwin

"You can't make a monkey out of us": Galen and genetics versus Darwin Diamandopoulos A. and Goudas P. Summary The views on the biological relationship between human and ape are polarized. O n e end is summarized by the axiom that "mon is the third chimpanzee", a thesis put forward in an indirect way initially by Charles Darwin in the 19 th century.The other is a very modern concept that although similar, the human and ape genomes are distinctly different. We have compared these t w o views on the subject w i t h the stance of the ancient medical w r i t e r Galen.There is a striking resemblance between current and ancient opinion on three key issues. Firstly, on the fact that man and apes are similar but not identical. Secondly, on the influence of such debates on fields much wider than biology.And finally, on the comparative usefulness of apes as a substitute for human anatomy and physiology studies. Resume Les points de vue concernant les liens biologiques existants entre etre humain et singe sont polarises selon une seule direction. A I'extreme, on pourrait resumer ce point de vue par I'axiome selon lequel « I'homme est le troisieme chimpanze ». Cette these fut indirectement soutenue par Charles Darwin, au I9eme siecle. L'autre point de vue est un concept tres moderne soutenant la similitude mais non I'identite entre les genomes de I'homme et du singe. Nous avons compare ces deux points de vue sur le sujet en mentionnant celui du medecin ecrivain Galien, dans I'Antiquite. -

Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen's Philosophical Speculation Became

Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 1 January 2013 Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions Paul Anthony Abilene Christian University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/conversations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Paul (2013) "Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions," Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/conversations/vol1/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conversations: A Graduate Student Journal of the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. Conversations Vol. 1 No. 1 May 2013 Sex, Sin and the Soul: How Galen’s Philosophical Speculation Became Augustine’s Theological Assumptions Paul A. Anthony Abilene Christian University Graduate School of Theology, History and Theology Abstract Augustine of Hippo may never have heard of Galen of Pergamum. Three centuries separated the two, as did an almost impassable geographic and cultural divide that kept the works of Galen and other Greek writers virtually unknown in the Latin west for a millennium. Yet Galenic assumptions about human sexuality and the materiality of the soul underlie Augustine’s signature doctrine of original sin. Galen’s influence was so widely felt in the Greek-speaking east that Christians almost immediately worked his assumptions into their own theologies. -

The Ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Galen on the Elderly

2017;65:325-328 REVIEW The ideas of Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Galen on the elderly A. Diamandopoulos EKPA, Louros Foundation, Greece For the sake of brevity, we will deal here with a very small fraction of the texts of ancient Greek writers on Old Age, in a period of roughly 600 years between the 5th century BC and the 2nd century AD. And geographically also, the area covered is but a negligent fraction of the globe. Aim. To comment on a very small fraction of the texts of ancient Greek writers on Old Age, in a period of roughly 600 years between the 5th century BC and the 2nd century AD. Materials and methods. We used extracts from the writings of Plato (The Republic), Aristotle (De Anima), Plutarch (Vitae Parallelae, Moralia) and Galen (De Marcore Liber). Results. Plato presents two sides of the stance of elderly, i.e. continuity (to continue to do what they were doing in their active years), and disengagement (describes the tendency after some age to go away from your previous straggles and to contemplate on the eternal values of spirituality). Aristotle explains why in old age death is painless, like the shutting out of a tiny feeble flame. Plutarch elaborates extensively on the need to accumulate physical and mental qualifications when we are young so that we can be able to consume them later, in our old age. He declares that “although old age has much to be shameful of, at least let us not to add the disgrace of wickedness”. Finally, the social role of each person shall not mutate with age. -

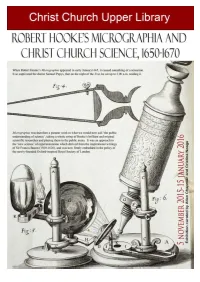

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

Greek Biology and Greek Medicine

BOOK REVIEWS Greek Biology and Greek Medicine. By Charles est investigators of living nature.” Singer Singer. Chapters in the History of Science. Gen quotes Muller’s studies on the embryology eral Editor Charles Singer, i. Oxford Univ. 1922. of the dogfish, made in 1840, which abso In this unpretentious little volume there lutely confirmed the observations of Aristotle is presented a most valuable study of the made two thousand years before. evolution of biology and medicine among The mode of reproduction of the cephalo the Greeks from the commencement of pods was quite accurately described by such studies down to the latest evidences Aristotle but his description was not gener of Greek influence in them. The remains of ally accepted nor was it confirmed until early Greek art dating from the seventh the nineteenth century. Singer quotes some and sixth century b.c. show “a closeness of Aristotle’s wonderfully vivid descriptions of observation of animal forms that tells of a of the somewhat obscure anatomy and people awake to the study of nature.” The physiology of marine animals. so-called Coan classificatory system a some Aristotle’s pupil and successor, Theo what crude classification of animals con phrastus (372-287 b.c.) may be justly tained in the work “On Regimen,” in the regarded as the founder of botanical science. Hippocratic Collection, dated the fifth As there was until the seventeenth century century b.c. “shows a close and accurate no adequate system of the classification of study of animal forms, a study that may be plants Theophrastus and his successors until justly called scientific.” The author pro that era had to content themselves with ceeds to quote a number of physiological descriptions of the individual plants accom and embryological studies and observations panied by pictorial representations. -

The Thorax in History 2. Hellenistic Experiment and Human Dissection

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.33.2.153 on 1 April 1978. Downloaded from Thorax, 1978, 33, 153-166 The thorax in history 2. Hellenistic experiment and human dissection R.K. FRENCH From the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, University of Cambridge The first anatomical revolution occurred in Alex- the dead body was essential to the ancient practice andria in the third century before Christ. To that of embalming, an Egyptian technique well known period we can trace the continuous historical line to the Greeks. The Greek philosophers, Plato and of our own ideas on the structure and function of Aristotle, emphasised the distinction between soul the body, important among which are those on the and body:' it was the immaterial soul that sur- thorax. For the first time, the human body was vived the death of the corporeal body, and the systematically explored in an attempt to under- soul, sharing no characteristics with the body, stand its structure, and, with some notable errors could not be affected by the postmortem mutila- from animal anatomy, the only source for 'human' tion of the body; there was no quasi-material after- anatomy in the preceding period, these anatomical life in human form, as so many cultures believed. ideas are recognisably similar to those of to-day. In a word, the old religious taboos no longer The physiological ideas of the Alexandrians, on applied. the other hand, are strikingly different from ours, Of fundamental importance in the development and their subsequent transformation will be exam- of human dissection in Alexandria was the exist- http://thorax.bmj.com/ ined in later articles. -

Anatomical Study in the Western World Before The

Acta Biomed 2019; Vol. 90, N. 4: 523-525 DOI: 10.23750/abm.v90i4.8738 © Mattioli 1885 Medical humanities Anatomical study in the Western world before the Middle Ages: historical evidence Andrea Alberto Conti, Ferdinando Paternostro Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale e Clinica, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy Summary. Although modern anatomy is commonly retained to begin in the XVI century, the roots of ana- tomical study in the Western world may be identified beforehand. An anatomical practice was present in the Western world well before the Middle Ages, starting in ancient Greece. Hippocrates of Cos (V-IV centuries B.C.) provided descriptions of the heart and vessels, and the so-called “Hippocratic Corpus” largely deals with anatomy. Aristotle of Stagira (IV century B.C.) was one of the first well-known scholars of the past to perform dissections of animals. The anatomical interest of Aristotle contained a “physiological” background too, since he was convinced that all parts of human organisms had one or more specific functions. Galen of Pergamum (II century A.D.) was the performer of hundreds of dissections of animals, and he described a great number of anatomical parts of apes, dogs, goats and pigs. The anatomical system of Galen became a gold standard for medicine for more than a thousand years, and in the Middle Ages (V-XV centuries A.D.) the human anatomy that was taught and acquired in European universities remained based on Galenic anatomy. In conclusion, Greek-speaking scholars between the IV century B.C. and the II century A.D. set the basis for the systematic dissection of animals and the comparative investigation of animal anatomical findings. -

Influence of Dioscorides on Simple Drugs Chapter of Ibn Sina’S the Canon of Medicine*

Influence of Dioscorides on Simple Drugs Chapter of Ibn Sina’s the Canon of Medicine* İbn-i Sina’nın Kanun Adlı Eserinin Basit İlaçlar Bölümünde Dioskorides Etkisi Özgür Kırani, Selim Kadıoğluii iTıp Tarihi ve Etik Bilim Doktoru, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1229-5497 iiProf.Dr. Çukurova Üniversitesi Tıp Tarihi ve Etik A.D., https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5803-3708 ABSTRACT Objectives: The aim of the study is determining the influence of Dioscorides on Ibn Sina in the context of simple drugs. Materials and Methods: The second book of The Canon of Medicine on simple drugs was screened and the articles on which Dioscorides cited were sought out and evaluated. Results: In the second book of The Canon of Medicine, 87 substances in which Dioscorides was referenced were identified. 75 of these substances are herbal, 6 animal and 6 mineral. Conclusion: As one of the important work of Greco-Roman medicine, De Materia Medica has a strong influence on Greco-Arab medicine. This is also confirmed by our study on simple drugs chapter of Ibn Sina’s The Canon of Medicine. Keywords: Dioscorides, Ibn Sina, Simple Drugs, Greco-Arab Medicine ÖZ Amaç: Çalışmanın amacı, basit ilaçlar bağlamında Dioskorides’in İbn-i Sina üzerindeki etkisini belirlemektir. Gereç ve Yöntem: Kanun’un basit ilaçlar üzerine olan ikinci kitabı taranmış ve Dioskorides’in anıldığı maddeler aranarak değerlendirmesi yapılmıştır. Bulgular: Kanun’un ikinci kitabında Dioskorides’in refere edildiği 87 madde tespit edilmiştir. Bunların 75’i bitkisel, 6’sı hayvansal ve 6’sı madenseldir. Sonuç: Greko-Roman tıbbının önemli eserlerinden biri olan De Materia Medica’nın Greko-Arap tıbbı üzerinde güçlü bir etkisi olmuştur. -

Medicine in Medieval England, 1250-1500

Medicine in medieval England, 1250‐1500 Medieval attitudes – the example of Hippocrates and Ideas about the causes of disease and illness Education Galen. Medieval ideas were so different from ours that it is easy to think they were just based on superstition or This factor is strongly linked to the influence of the church because the Church controlled education, magic, that people were ignorant and even stupid. This is not the case. Most medieval ideas about what including how physicians were trained at universities. There were in fact very few physicians in England People respected traditional ideas. Doctors therefore caused disease were rational and logical, fitting people’s ideas about how the world worked. They believed (see you at than 100 in the 1300s), partly because the training took seven years I’m very few people could followed ideas of Hippocrates who lived over 1500 years that god controlled everything, so god must send disease and illness. Ideas that blamed bad air and the afford the cost. earlier in Ancient Greece. Claudius Galen was also Greek movement of planets were also linked to God because it was god who made the planets move or sent the bad air to spread disease. but worked in Rome 500 years after Hippocrates and was The main part of doctors training was reading the books of Hippocrates and Galen, along with translations of books by Arab doctors such as Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Europe) and al‐Razi (known even more respected. He wrote over 300 medical books Physicians continued to believe in the Theory of the four Humours which had been developed by as Rhazes). -

A History of the Optic Nerve and Its Diseases

Eye (2004) 18, 1096–1109 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/04 $30.00 www.nature.com/eye 1 2 CAMBRIDGE OPHTHALMOLOGICAL SYMPOSIUM A history of the C Reeves and D Taylor optic nerve and its diseases Abstract The optic nerve through history We will trace the history of ideas about Introduction optic nerve anatomy and function in the The history of concepts of nerve function is one Western world from the ancient Greeks to the of the longest in the evolution of the early 20th century and show how these neurosciences although Clarke and Jacyna1 influenced causal theories of optic nerve suggest that it falls naturally into three epochs. diseases. Greek and Roman humoral The first was prior to Luigi Galvani’s (1737– physiology needed a hollow optic nerve, 1798) theory of animal electricity (galvanism), the obstruction of which prevented the published in 1791.2 The second encompassed flow of visual spirit to and from the brain the period 1791 to the 1840s when the nature of and resulted in blindness. Medieval galvanism and its role in nerve conduction was physicians understood that the presence studied. The third began during the 1840s when of a fixed dilated pupil indicated optic Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818–1896) established nerve obstruction, preventing the passage the discipline of electrophysiology as a of visual spirit, and that cataract surgery in laboratory science. We might now add a such cases would not restore sight. fourthFa very recent ‘modern’ era, which During the Renaissance, the organ of includes imaging, biochemistry, and molecular vision was transferred from the lens to the genetics. -

Galen of Pergamon a Sketch of an Original Eclectic and Lntegrative Practitioner, and His System of Medicine

Hnstory and Fhrlosophy Galen of Pergamon A Sketch of an Original Eclectic and lntegrative Practitioner, and His System of Medicine by Peter Holmes, L.Ac., M.H., A.H.G. The Greek doctor, philosopher and natural scientist believe that coming directly to grips with Galen's work Claudios Galenos (c. 129-199), also known as Galen without prejudice may hold a key that can help us inte- of Pergamon, holds a unique position in the history of grate the various current types ofherbal medicine into traditional Greek-Western medicine. An original a powerful new synthesis. thinkeq researcher, writer and practitioner of extraor- Summarizing Galen's enormous contribution to dinary caliber, his life and work is characterized by an Greek-Western medicine and scientific thought, and unbridled creative energy that has been compared to detailing his contemporary significance in a brief arti- that of Alexander the Great (Lichtenthaeler 1982). cle is challenging and humbling. challenging Galen's influence in medicine, philosophy and the nat- Equally and us having terms ural sciences was so widespread and longJasting that humbling for is to come to with the his very name was given to the Greek-Western medical very lack of transmission of our own traditional problem system that lasted nght up to the nineteenth century, holistic medical system in modern times. The under the name of "Galenic medicine." His work in the we now face is one of epistemology: given the scanti- quality area of herbal medicine was so influential that herbal ness and poor of available