The Narrow Road to Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

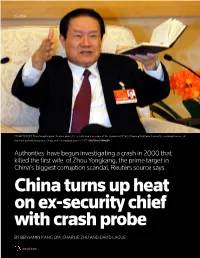

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

Sopa-Scoopzhoutarget

Friday, August 30, 2013 A3 Beam me up LEADING THE NEWS K-pop stars are embracing hologram COMMERCE Oil giants technology to reach a wider audience > L I F E C 7 banned Unwelcome guest Create your dream home Health headache from new Aquino cancels visit to China: Chic, stylish furniture Migraines can cause INVESTMENT TEAMS TO BE REINED IN Beijing says he was never and accessories for permanent brain damage projects invited in the first place discerning buyers and raise risk of strokes Commerce Ministry targets extravagance by delegations sent Foreign direct investment is a Previously, investment jun- key economic indicator used to kets were believed to be immune > LEA D ING T HE N EWS A 3 > 20-PAG E SPE CIA L REP O R T > WORLD A15 to Hong Kong and Macau to seek investment for their regions gauge officials’ performance, and from the campaign against offi- Beijing makes state ................................................ dozens of delegations from local cial extravagance. overstated the number of partici- His remarks followed the flag- governments flock to Hong Kong The The People’s Daily said busi- energy companies pay Daniel Ren pants and the value of deals ship newspaper’s harsh criticism every year to seek such invest- ness delegations stayed in five- [email protected] phenomenon the price for failing to signed during their promotional on Monday of investment dele- ments. star hotels and invited business- activities. gations travelling to Hong Kong. Yao admitted that the delega- reflects a severe men to expensive restaurants, meet pollution targets The Ministry of Commerce has “They were desperate to get This was the first time that a tions played a positive role in level of spending as much as 1,000 yuan pledged to rein in extravagance abig number of foreign business- Communist Party mouthpiece spurring the nation’s economic (HK$1,260) per head for a break- ............................................... -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement May 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC .......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 44 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 45 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 52 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 May 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC -

Xi's System, Xi's Men: After the March 2018 National People's Congress

Xi’s System, Xi’s Men: After the March 2018 National People’s Congress Barry Naughton The National People’s Congress meeting in March launched a significant administrative reorganization and approved the appointment of a new generation of economic technocrats. The technocrats are skilled and generally support market-oriented reforms. The reorganization is generally market-friendly, but its main purpose is to create a more disciplined and accountable administration to serve as an instrument for Xi Jinping. Last year, after the 19th Communist Party Conference in October, Xi Jinping laid out a general economic program for the next three years. This March, at the 13th session of the National People’s Congress, Xi introduced significant changes in the administrative structure and fleshed out the personnel assignments that will prevail for the next few years. These changes demonstrate once again how firmly Xi is in control of economic policy and personnel. Even if Xi had not also changed the constitution to eliminate term limits for the president (himself) and vice-president, these changes would be enough to demonstrates Xi’s power and ruling style. The policy framework laid out at the end of 2017 allows space for renewed system reforms. As explained in the previous contribution to CLM, successful economic management in 2017 has permitted Xi to prefer “high quality” growth over “high speed” growth, and in particular to launch “three battles”: reducing financial risk; eliminating poverty; and improving the environment.1 While deepening economic conflicts with the United States have certainly complicated the policy environment, until now the Xi administration has stuck to this basic policy orientation. -

Ministry Touts Plan to Improve Infrastructure

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Thursday, January 14, 2021 | 5 CHINA Planting fruit helps Healthy after 100 days Late report bring prosperity to of mine Aksu in Xinjiang blast leads By MAO WEIHUA in Urumqi for orchards or fruit companies to discipline and CHEN MEILING regardless of their age, as long as they’re healthy, willing and able to By ZHAO RUIXUE in Jinan Saypidin Yasin said planting and work, said Yang Xiaoyan, an offi- [email protected] selling walnuts has changed his cial of Baicheng’s agriculture and life in the Xinjiang Uygur autono- rural affairs bureau. Those responsible for the late mous region. “For example, 90 percent of the reporting of an explosion at a gold He used to take odd jobs to sup- workers at our potato starch facto- mine under construction in eastern port his family of four in Yalhuz ry are from poor families,” Yang China have been placed under con- Terak village, Aksu prefecture. said. trol, according to a news confer- Despite working hard, his annual “Our fruit business is expand- ence on Wednesday, as rescue income was about 10,000 yuan ing, and the white apricots and teams were racing to save workers ($1,544) — hardly enough to cover grapes are well enjoyed by cus- trapped underground. expenses. tomers. With further development The blast occurred at 2 pm on He learned that many of his of the business, more jobs will be Sunday at the Hushan mine in Qi- neighbors had made big money by created.” xia, under the administration of planting walnuts, and he decided In the past, farmers mainly Yantai city in Shandong province. -

China and the SDR Financial Liberalization Through the Back Door

CIGI Papers No. 170 — April 2018 China and the SDR Financial Liberalization through the Back Door Barry Eichengreen and Guangtao Xia CIGI Papers No. 170 — April 2018 China and the SDR: Financial Liberalization through the Back Door Barry Eichengreen and Guangtao Xia CIGI Masthead Executive President Rohinton P. Medhora Deputy Director, International Intellectual Property Law and Innovation Bassem Awad Chief Financial Officer and Director of Operations Shelley Boettger Director of the International Law Research Program Oonagh Fitzgerald Director of the Global Security & Politics Program Fen Osler Hampson Director of Human Resources Susan Hirst Interim Director of the Global Economy Program Paul Jenkins Deputy Director, International Environmental Law Silvia Maciunas Deputy Director, International Economic Law Hugo Perezcano Díaz Director, Evaluation and Partnerships Erica Shaw Managing Director and General Counsel Aaron Shull Director of Communications and Digital Media Spencer Tripp Publications Publisher Carol Bonnett Senior Publications Editor Jennifer Goyder Publications Editor Susan Bubak Publications Editor Patricia Holmes Publications Editor Nicole Langlois Publications Editor Lynn Schellenberg Graphic Designer Melodie Wakefield For publications enquiries, please contact [email protected]. Communications For media enquiries, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2018 by the Centre for International Governance Innovation The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Board of Directors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice.