Equal Protection Under the Alabama Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus V. Alabama, ___ F.Supp.3D ___, 2013 WL 3976626 (M.D

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS et al., Appellants, v. THE STATE OF ALABAMA et al., Appellees. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Middle District Of Alabama --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT --------------------------------- --------------------------------- EDWARD STILL JAMES U. BLACKSHER 130 Wildwood Parkway Counsel of Record Suite 108 PMB 304 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35209 Birmingham, AL 35201 E-mail: [email protected] 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 PAMELA S. KARLAN E-mail: 559 Nathan Abbott Way [email protected] Stanford, CA 94305 E-mail: [email protected] U.W. CLEMON WHITE ARNOLD & DOWD P. C . 2025 Third Avenue North, Suite 500 Birmingham, AL 35203 E-mail: [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a state violates the requirement of one person, one vote by enacting a state legislative redis- tricting plan that results in large and unnecessary population deviations for local legislative delegations that exercise general governing authority over coun- ties. ii PARTIES The following were parties in the Court below: Plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: Alabama Legislative Black Caucus Bobby Singleton Alabama Association of Black County Officials Fred Armstead George Bowman Rhondel Rhone Albert F. Turner, Jr. Jiles Williams, Jr. Plaintiffs in consolidated Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-1081: Demetrius Newton Alabama Democratic Conference Framon Weaver, Sr. Stacey Stallworth Rosa Toussaint Lynn Pettway Defendants in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: State of Alabama Jim Bennett, Alabama Secretary of State Defendants in consolidated Civil Action No. -

Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth

Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal Volume 2003 | Number 2 Article 10 Fall 3-2-2003 Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation John Herbert Roth, Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field, 2003 BYU Educ. & L.J. 739 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj/vol2003/iss2/10 . This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATION FUNDING AND THE ALABAMA EXAMPLE: ANOTHER PLAYER ON A CROWDED FIELD John Herbert Roth* I. INTRODUCTION If the fundamental task of the school is to prepare children for life, the curriculum must be as wide as life itself. It should be thought of as comprising all the activities and the experiences afforded by the community through the school, whereby the children may be prepared to participate in the life of the community.' During the birth of the United States, when the many notable proponents of a system of free public education in this nation envisioned the benefits of an educated multitude, it is doubtful that they could have conceived of the free public school system that has become today's reality. Although it is manifest that an educated citizenry is an objective of the utmost importance in any organized and civilized society, the debate concerning how to provide for and fund a system of free public education has continued with little repose. -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK, AGNES DUSABE, MUSA EZEIRIG, ZARPKA GREEN, DUSTY NYONEE, ANDABRAHAM TARPEH, Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. RYAN HOENICKE, DANIELLE WILLIAMS, CLEO BOYD, ALLEN FINCHUM, TERRY VAN HUYSEN, JIM BAILEY, MAX CARKHUFF, SCOTT GEMMELL, JERRY VANBROGEN and TPI IOWA, LLC, Defendants, INSURANCE COMPANY STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA, Defendant-Appellee. APPEAL FROM THE IOWA DISTRICT COURT FOR JASPER COUNTY THE HONORABLE TERRY RICKERS APPELLEE’S BRIEF (ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED) Keith P. Duffy, AT0010911 Mitchell R. Kunert, AT0004458 NYEMASTER GOODE, P.C. 700 Walnut St., Ste. 1600 Des Moines, IA 50309 ELECTRONICALLY FILED AUG 17, 2018 CLERK OF SUPREME COURT Phone: (515) 283-3100 Fax: (515) 283-8045 Email: [email protected] [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................ 3 ISSUES PRESENTED .................................................................... 5 ROUTING STATEMENT ................................................................ 7 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................................................... 8 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................... 9 STANDARD OF REVIEW AND ERROR PRESERVATION .......... 9 ARGUMENT .................................................................................... 9 I. Iowa Code Section 517.5 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause Contained in Article 1, Section 6 of the Iowa Constitution. ......................................................... -

Restoring the Right to Vote | 2 Criminal Disenfranchisement Laws Across the U.S

R E S T O R I N G T H E RIGHT TO VOTE Erika Wood Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution – part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group – the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advo- cacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S RIGHT TO VOTE PROJECT The Right to Vote Project leads a nationwide campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal convictions. Brennan Center staff counsels policymakers and advocates, provides legal and constitutional analysis, drafts legislation and regulations, engages in litigation challenging disenfranchising laws, surveys the implementation of existing laws, and promotes the restoration of voting rights through public outreach and education. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Erika Wood is the Deputy Director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice where she lead’s the Right to Vote Project, a national campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal records, and works on redistricting reform as part of the Center’s Government Accountability Project. Ms. Wood is an Adjunct Professor at NYU Law School where she teaches the Brennan Center Public Policy Advocacy Clinic. -

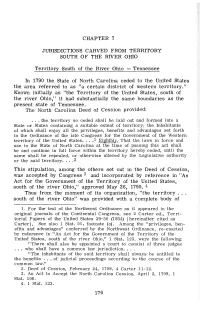

Chapter 7 Jurisdictions Carved from Territory

CHAPTER 7 JURISDICTIONS CARVED FROM TERRITORY SOUTH OF THE RIVER OHIO Territory South of the River Ohio - Tennessee In 1790 the State of North Carolina ceded to the United States the area referred to as "a certain district of western territory." Known initially as "the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," it had substantially the same boundaries as the present state of Tennessee. The North Carolina Deed of Cession provided: ... the territory so ceded shall be laid out and formed into a State or States containing a suitable extent of territory; the Inhabitants of which shall enjoy all the privileges, benefits and advantages set forth in the Ordinance of the late Congress for the Government of the Western territory of the United States ... .1 Eighthly, That the laws in force and use in the State of North Carolina at the time of passing this act shall be and continue in full force within the territory hereby ceded, until the same shall be repealed, or otherwise altered by the Legislative authority or the said territory ....2 This stipulation, among the others set out in the Deed of Cession, was accepted by Congress 3 and incorporated by reference in "An Act for the Government of the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," approved May 26, 1790. 4 Thus from the moment of its organization, "the territory . south of the river Ohio" was provided with a complete body of 1. For the text of the Northwest Ordinance as it appeared in the original journals of the Continental Congress, see 2 Carter ed., Terri torial Papers of the United States 39-50 (1934) [hereinafter cited as Carter]. -

BRNOVICH V. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BRNOVICH, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARIZONA, ET AL. v. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–1257. Argued March 2, 2021—Decided July 1, 2021* Arizona law generally makes it very easy to vote. Voters may cast their ballots on election day in person at a traditional precinct or a “voting center” in their county of residence. Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16–411(B)(4). Arizonans also may cast an “early ballot” by mail up to 27 days before an election, §§16–541, 16–542(C), and they also may vote in person at an early voting location in each county, §§16–542(A), (E). These cases involve challenges under §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) to aspects of the State’s regulations governing precinct-based election- day voting and early mail-in voting. First, Arizonans who vote in per- son on election day in a county that uses the precinct system must vote in the precinct to which they are assigned based on their address. See §16–122; see also §16–135. -

An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama State

OCTOBER 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 When voters go to the polls on November 6, they'll not only be electing a governor, legislators, and other state and local officials, they'll also be asked to vote on 19 new amendments to the Alabama Constitution of 1901. Voters statewide will decide whether to add four proposed amendments that will apply throughout the state. In addition, 15 local amendments will be voted on only in the counties in which they would apply. The Alabama Constitution is unusual. It is the longest and most amended constitution in the world. There are currently 928 amendments to the Alabama Constitution. Most state and national constitutions lay out broad principles, set the basic structure of the government, and impose limitations on governmental power. Such broad provisions are included in the Alabama Constitution. Alabama’s constitution delves into the minute details of government, requiring constitutional amendments for basic changes that would be made by the Legislature or by local governments in most states. Instead of broad provisions applicable to the whole state, about three-quarters of the amendments to the Alabama Constitution pertain to particular local governments. Amendments establish pay rates of public officials and spell out local property tax rates. A recent amendment, Amendment 921, grants municipal governments in Baldwin County the power to regulate golf carts on public streets. Until serious reforms are made, this practice will continue and the Alabama Constitution will continue to swell. -

Special and Local Legislation Lyman H

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 4 Article 1 1936 Special and Local Legislation Lyman H. Cloe Sumner Marcus Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Cloe, Lyman H. and Marcus, Sumner (1936) "Special and Local Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 24 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol24/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY LAW JOURNAL Volume XXI1r Mlay, 1936 Number 4 SPECIAL AND LOCAL LEGISLATION By Lyx" H. CLoE* AND SumNuM MLoust With the exception of four New England states' the con- stitutions of all others contain restrictions upon local and special legislation. Uniformity in such provisions is lacking. They range in style and effect from these which appear to be no more than a declaration of policy2 or procedural requirement 3 to the inclusive type which not only places an absolute prohibition on such legislation in certain named instances, but in all other 4 cases where a general law can be made applicable. An accurate classification of these provisions is not a sim- ple matter. Few are identical in wording. Some, though pat- ently at variance, appear to have received synonymous appli- cation. -

Barriers to Voting in Alabama (2020)

Barriers to Voting in Alabama A Report by the Alabama Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights February 2020 i Advisory Committees to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights By law, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has established an advisory committee in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The committees are composed of state citizens who serve without compensation. The committees advise the Commission of civil rights issues in their states that are within the Commission’s jurisdiction. More specifically, they are authorized to advise the Commission in writing of any knowledge or information they have of any alleged deprivation of voting rights and alleged discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, national origin, or in the administration of justice; advise the Commission on matters of their state’s concern in the preparation of Commission reports to the President and the Congress; receive reports, suggestions, and recommendations from individuals, public officials, and representatives of public and private organizations to committee inquiries; forward advice and recommendations to the Commission, as requested; and observe any open hearing or conference conducted by the Commission in their states. ii Letter of Transmittal To: The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Catherine E. Lhamon (Chair) Debo P. Adegbile David Kladney Gail Heriot Michael Yaki Peter N. Kirsanow Stephen Gilchrist From: The Alabama Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights The Alabama State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (hereafter “the Committee”) submits this report, “Barriers to Voting” as part of its responsibility to examine and report on civil rights issues in Alabama under the jurisdiction of the Commission. -

Barriers to Voting in Louisiana

Barriers to Voting in Louisiana A Briefing Paper by the Louisiana Advisory Committee for the United States Commission on Civil Rights June 2018 Advisory Committees to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights By law, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has established an advisory committee in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The committees are composed of state citizens who serve without compensation. The committees advise the Commission of civil rights issues in their states that are within the Commission’s jurisdiction. More specifically, they are authorized to advise the Commission in writing of any knowledge or information they have of any alleged deprivation of voting rights and alleged discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, national origin, or in the administration of justice; advise the Commission on matters of their state’s concern in the preparation of Commission reports to the President and the Congress; receive reports, suggestions, and recommendations from individuals, public officials, and representatives of public and private organizations to committee inquiries; forward advice and recommendations to the Commission, as requested; and observe any open hearing or conference conducted by the Commission in their states. Louisiana Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights The Louisiana Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights submits this briefing paper detailing civil rights concerns associated with barriers to voting in Louisiana. The Committee submits this report as part of its responsibility to study and report on civil rights issues in the state of Louisiana. The contents of this report are primarily based on testimony the Committee heard during hearings on November 15, 2017 in Grambling, Louisiana and December 6, 2017 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.