Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon Richard H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus V. Alabama, ___ F.Supp.3D ___, 2013 WL 3976626 (M.D

No. _________ ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS et al., Appellants, v. THE STATE OF ALABAMA et al., Appellees. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Middle District Of Alabama --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT --------------------------------- --------------------------------- EDWARD STILL JAMES U. BLACKSHER 130 Wildwood Parkway Counsel of Record Suite 108 PMB 304 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35209 Birmingham, AL 35201 E-mail: [email protected] 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 PAMELA S. KARLAN E-mail: 559 Nathan Abbott Way [email protected] Stanford, CA 94305 E-mail: [email protected] U.W. CLEMON WHITE ARNOLD & DOWD P. C . 2025 Third Avenue North, Suite 500 Birmingham, AL 35203 E-mail: [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether a state violates the requirement of one person, one vote by enacting a state legislative redis- tricting plan that results in large and unnecessary population deviations for local legislative delegations that exercise general governing authority over coun- ties. ii PARTIES The following were parties in the Court below: Plaintiffs in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: Alabama Legislative Black Caucus Bobby Singleton Alabama Association of Black County Officials Fred Armstead George Bowman Rhondel Rhone Albert F. Turner, Jr. Jiles Williams, Jr. Plaintiffs in consolidated Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-1081: Demetrius Newton Alabama Democratic Conference Framon Weaver, Sr. Stacey Stallworth Rosa Toussaint Lynn Pettway Defendants in Civil Action No. 2:12-CV-691: State of Alabama Jim Bennett, Alabama Secretary of State Defendants in consolidated Civil Action No. -

Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth

Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal Volume 2003 | Number 2 Article 10 Fall 3-2-2003 Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field John Herbert Roth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation John Herbert Roth, Education Funding and the Alabama Example: Another Player on a Crowded Field, 2003 BYU Educ. & L.J. 739 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/elj/vol2003/iss2/10 . This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUCATION FUNDING AND THE ALABAMA EXAMPLE: ANOTHER PLAYER ON A CROWDED FIELD John Herbert Roth* I. INTRODUCTION If the fundamental task of the school is to prepare children for life, the curriculum must be as wide as life itself. It should be thought of as comprising all the activities and the experiences afforded by the community through the school, whereby the children may be prepared to participate in the life of the community.' During the birth of the United States, when the many notable proponents of a system of free public education in this nation envisioned the benefits of an educated multitude, it is doubtful that they could have conceived of the free public school system that has become today's reality. Although it is manifest that an educated citizenry is an objective of the utmost importance in any organized and civilized society, the debate concerning how to provide for and fund a system of free public education has continued with little repose. -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 17-2068 DILLON CLARK, AGNES DUSABE, MUSA EZEIRIG, ZARPKA GREEN, DUSTY NYONEE, ANDABRAHAM TARPEH, Plaintiffs-Appellants, vs. RYAN HOENICKE, DANIELLE WILLIAMS, CLEO BOYD, ALLEN FINCHUM, TERRY VAN HUYSEN, JIM BAILEY, MAX CARKHUFF, SCOTT GEMMELL, JERRY VANBROGEN and TPI IOWA, LLC, Defendants, INSURANCE COMPANY STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA, Defendant-Appellee. APPEAL FROM THE IOWA DISTRICT COURT FOR JASPER COUNTY THE HONORABLE TERRY RICKERS APPELLEE’S BRIEF (ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED) Keith P. Duffy, AT0010911 Mitchell R. Kunert, AT0004458 NYEMASTER GOODE, P.C. 700 Walnut St., Ste. 1600 Des Moines, IA 50309 ELECTRONICALLY FILED AUG 17, 2018 CLERK OF SUPREME COURT Phone: (515) 283-3100 Fax: (515) 283-8045 Email: [email protected] [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................ 3 ISSUES PRESENTED .................................................................... 5 ROUTING STATEMENT ................................................................ 7 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................................................... 8 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................... 9 STANDARD OF REVIEW AND ERROR PRESERVATION .......... 9 ARGUMENT .................................................................................... 9 I. Iowa Code Section 517.5 Does Not Violate the Equal Protection Clause Contained in Article 1, Section 6 of the Iowa Constitution. ......................................................... -

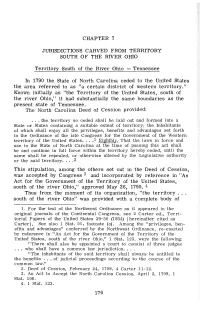

Chapter 7 Jurisdictions Carved from Territory

CHAPTER 7 JURISDICTIONS CARVED FROM TERRITORY SOUTH OF THE RIVER OHIO Territory South of the River Ohio - Tennessee In 1790 the State of North Carolina ceded to the United States the area referred to as "a certain district of western territory." Known initially as "the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," it had substantially the same boundaries as the present state of Tennessee. The North Carolina Deed of Cession provided: ... the territory so ceded shall be laid out and formed into a State or States containing a suitable extent of territory; the Inhabitants of which shall enjoy all the privileges, benefits and advantages set forth in the Ordinance of the late Congress for the Government of the Western territory of the United States ... .1 Eighthly, That the laws in force and use in the State of North Carolina at the time of passing this act shall be and continue in full force within the territory hereby ceded, until the same shall be repealed, or otherwise altered by the Legislative authority or the said territory ....2 This stipulation, among the others set out in the Deed of Cession, was accepted by Congress 3 and incorporated by reference in "An Act for the Government of the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," approved May 26, 1790. 4 Thus from the moment of its organization, "the territory . south of the river Ohio" was provided with a complete body of 1. For the text of the Northwest Ordinance as it appeared in the original journals of the Continental Congress, see 2 Carter ed., Terri torial Papers of the United States 39-50 (1934) [hereinafter cited as Carter]. -

An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama State

OCTOBER 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama Constitution: 2018 When voters go to the polls on November 6, they'll not only be electing a governor, legislators, and other state and local officials, they'll also be asked to vote on 19 new amendments to the Alabama Constitution of 1901. Voters statewide will decide whether to add four proposed amendments that will apply throughout the state. In addition, 15 local amendments will be voted on only in the counties in which they would apply. The Alabama Constitution is unusual. It is the longest and most amended constitution in the world. There are currently 928 amendments to the Alabama Constitution. Most state and national constitutions lay out broad principles, set the basic structure of the government, and impose limitations on governmental power. Such broad provisions are included in the Alabama Constitution. Alabama’s constitution delves into the minute details of government, requiring constitutional amendments for basic changes that would be made by the Legislature or by local governments in most states. Instead of broad provisions applicable to the whole state, about three-quarters of the amendments to the Alabama Constitution pertain to particular local governments. Amendments establish pay rates of public officials and spell out local property tax rates. A recent amendment, Amendment 921, grants municipal governments in Baldwin County the power to regulate golf carts on public streets. Until serious reforms are made, this practice will continue and the Alabama Constitution will continue to swell. -

Special and Local Legislation Lyman H

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 4 Article 1 1936 Special and Local Legislation Lyman H. Cloe Sumner Marcus Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Cloe, Lyman H. and Marcus, Sumner (1936) "Special and Local Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 24 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol24/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KENTUCKY LAW JOURNAL Volume XXI1r Mlay, 1936 Number 4 SPECIAL AND LOCAL LEGISLATION By Lyx" H. CLoE* AND SumNuM MLoust With the exception of four New England states' the con- stitutions of all others contain restrictions upon local and special legislation. Uniformity in such provisions is lacking. They range in style and effect from these which appear to be no more than a declaration of policy2 or procedural requirement 3 to the inclusive type which not only places an absolute prohibition on such legislation in certain named instances, but in all other 4 cases where a general law can be made applicable. An accurate classification of these provisions is not a sim- ple matter. Few are identical in wording. Some, though pat- ently at variance, appear to have received synonymous appli- cation. -

James U. Blacksher Attorney at Law Phone: 205-591-7238 P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, AL 35201 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-Mail: Jblacksher@Ns

James U. Blacksher P.O. Box 636 Attorney at Law Birmingham, AL 35201 Phone: 205-591-7238 Fax: 866-845-4395 E-mail: [email protected] Statement of James U. Blacksher The Subcommittee on Elections of the Committee on House Administration Field Hearing, Birmingham, AL, May 13, 2019 Voting Rights and Election Administration in Alabama My name is James Blacksher. Thank you for inviting me to testify. I am a white native of Alabama and have been practicing law in Alabama since 1971, engaged primarily in representing African Americans in civil rights and voting rights litigation. I argued – and lost – City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980) in the Supreme Court, but with the help of co-counsel we won on remand to the district court. I testified in Congressional hearings leading to enactment of the 1982 Voting Rights Amendments. Four years later the Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) cited and adopted the three-prong test proposed in my Hastings Law Review article for purposes of establishing a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. With Edward Still and Larry Menefee, I represented plaintiffs in the Dillard v. Crenshaw County class action, which changed the method of electing members of over 180 local governments in Alabama. I have represented African Americans in litigation following redistricting of the Alabama House and Senate districts and Congressional districts in every decade since the 1980 census. Most recently, I represented the plaintiffs before the Supreme Court in Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama (2015), which held that many of the Alabama House and Senate districts were racially gerrymandered. -

United States (1950-2018)

United States Self-rule INSTITUTIONAL DEPTH AND POLICY SCOPE The United States (US) has, for the most part, two regional tiers: states and, in the more populous and older states, counties. Counties fall under the jurisdiction of state governments. We also score two metropolitan governments, The Metropolitan Council in Minnesota since 1976 and Metro in Oregon since 1979. In addition, there are Indian tribes and until 1959 there were also two territories, Alaska and Hawaii. The District of Columbia has a special status as capital district. Puerto Rico is an Associated Free State with the US (Estado Libre Asociado, Elazar 1991: 325).1 The US constitution contains a list of expressed federal competences, encompassing taxation, the military, currency, commerce with Indian tribes, interstate and foreign commerce, and naturalization (C 1788, Art. 1.8). In addition, an elastic clause gives the federal government authority to pass any law “necessary and proper” for the execution of its express powers (C 1788, Art. 1.8). Competences not delegated to the federal government and not forbidden to the states are reserved to the states (C 1788, Amendment X) but federal law has supremacy over state law (C 1788, Art. 6). States have extensive competences, among them primary responsibility for education, social welfare, regional development, local government, civil and criminal law, and health and hospitals (Dinan 2012; Hueglin and Fenna 2006: 151–156; Schram 2002; Watts 1999a, 2008). The federal government has near exclusive authority over citizenship (including naturalization) and immigration (Tarr 2005: 399–400). The power of Congress to admit aliens into the country under conditions it lays down is exclusive of state regulation. -

An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama State Constitution: 2016

OCTOBER1 2016 An Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments to the Alabama State Constitution: 2016 Analysis of Proposed Statewide Amendments for the November 8 General Election When Alabama voters go to the polls on November 8, they will be asked to consider adding 35 more amendments to the Alabama Constitution. PARCA has compiled a summary of each of the 14 amendments that will appear on the ballot statewide. Alabama already has the nation’s longest constitution — about 12 times longer than the national average. Since its adoption in 1901, the Alabama Constitution has been amended 895 times. In principle, constitutions are meant to lay out the fundamental powers of government and establish a statewide framework for its operation, leaving the state legislature and local legislative bodies the task of carrying out work within those limits. Alabama’s Constitution, by contrast, is minutely detailed with a multitude of amendments that create local exceptions that apply to individual jurisdictions, as well as provisions that apply statewide. The problem stems from the constitution strictly limiting the powers of local governments. Almost immediately after its adoption, the constitution began to accumulate amendments, most of which created local exceptions to state constitutional principles. November’s ballot continues that practice. Of the 35 amendments proposed, 25 apply to a single jurisdiction. Of the total, 14 amendments will be voted on statewide. Of those, 10 will affect the state as a whole, and four pertain to an individual locality but are being voted on by voters throughout the state. Of those local amendments being considered statewide, one is a proposal to raise the maximum age of the probate judge in Pickens County to 75. -

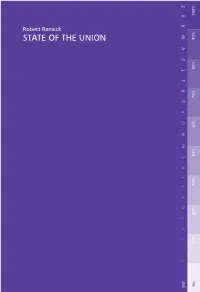

State of the Union

VW STU PQR STATE OFTHEUNION STATE Robert Ransick MNO KL HIJ EFG CD B A yes: XYZ no: 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Alaska Marriage Amendment, 1998 Nebraska Initiative 416, 2000 A vote “FOR” will amend the Nebraska Constitution to pro- vide that only marriage between a man and a woman shall be valid or recognized in Nebraska, and to provide that the unit- ing of two persons of the same sex in a civil union, domestic partnership or other similar same-sex relationship shall not be valid or recognized in Nebraska. This measure would amend the Declaration of Rights section of the Alaska Constitution to limit marriage. The amendment A vote “AGAINST” will not amend the Nebraska Constitution would say that to be valid, a marriage may exist only be- in the manner described above. tween one man and one woman. Shall the Nebraska Constitution be amended to provide that only marriage between a man and a woman shall be valid or recognized in Nebraska, and to provide further that the unit- ing of two persons of the same sex in a civil union, domestic partnership, or other similar same-sex relationship shall not be valid or recognized in Nebraska? Yes 152,965 68.1% Yes 450,073 70% No 71,631 31.9% No 189,555 30% Nevada Question 2, 2002 Arkansas Constitutional Amendment 3, 2004 (NOTE - First approved by the voters in 2000. Nevada requires constitutional initiatives to be approved at two successive An Amendment Concerning Marriage general elections.) Providing that marriage consists only of the union of one Shall the Nevada Constitution be amended -

Congratulations 2010 CMO Graduates!

The Alabama Municipal Journal September 2010 Volume 68, Number 3 Congratulations 2010 CMO Graduates! Contents A Message from the Editor ................................. 4 Journal The Presidents’s Report ...................................... 5 2010 CMO Graduation Ceremony Held Aug. 10 Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities September 2010 • Volume 68, Number 3 Municipal Overview ............................................7 Cities 101 OFFICERS CHARLES H. MURPHY, Mayor, Robertsdale, President The Legal Viewpoint ............................................ 9 THOMAS O. MOORE, Councilmember, Demopolis, Vice President Dedication of Lands PERRY C. ROQUEMORE, JR., Montgomery, Executive Director CHAIRS OF THE LEAGUE’S STANDING COMMITTEES Legal Clearinghouse .........................................16 Committee on State and Federal Legislation ACCMA Summer Conference ............................ 18 DEBBIE QUINN, Councilmember, Fairhope, Chair SADIE BRITT, Councilmember, Lincoln,Vice Chair 2010 Basic and Advanced CMO Graduates ...... 19 Committee on Finance, Administration and Intergovernmental Relations GARY FULLER, Mayor, Opelika, Chair 2010: Year of Alabama’s Small Towns and Down- DAVID HOOKS, Councilmember, Homewood, Vice Chair towns (Sept., Oct. and Nov. events) ................... 20 Committee on Energy, Environment and Natural Resources DEAN ARGO, Council President, Prattville, Chair 2011 Municipal Photo Contest .......................... 22 RUSTY JESSUP, Mayor, Riverside, Vice Chair Committee on Community and Economic Development