Building a Better Mousetrap: Patenting Biotechnology In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tropic Times

Gift 1fihe P ; aC,Jan0 the Tropic Times Vol. 11, No. 44 Quarry Heights, Republic of Panama Dec. 4,1989 Malta summit yields hope for Soviet recovery VALLETTA, Malta (UPI) - Gorbachev made the return trip to Bush that the West would not try to Communist rule, Gorbachev arrived Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev Moscow, arriving late Sunday night, dictate the speed of change in Eastern in Malta seeking Bush's understand- emerged Sunday from his storm- the official Soviet news agency Tass Europe. ing. plagued summit with President Bush reported. With Czechoslovakia, Hungary Bush's assurances he would not go with the prize he sought - a promise Giorgi Arbatov, a longtime adviser and even East Germany moving "demonstrating on the top of the of the U.S. economic cooperation he to Gorbachev and head of Mocow's dramatically away from one-party Berlin Wall to show that we are needs to rebuild the Soviet economy. U.S.-Canada Institute think-tank, happy" visibly pleased Gorbachev. The Malta talks hold the promise was more effusive about the Also on the table was a menu of of the "political impetus that we have economic helping hand offered by three possible arms agreements: been lacking" in economic reform the United States. cutting long-range strategic efforts, Gorbachev told a joint press the United States weapons, banning the production of conference with Bush aboard the "Thechemical weapons and reducing Soviet cruise liner Maxim Gorky. the end of its economic war against conventional forces in Europe - all In his package of proposals to the Soviet Union," said Arbatov. -

The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family

Chapter One The Decline and Fall of the Pirates Family The 1980–1985 Seasons ♦◊♦ As over forty-four thousand Pirates fans headed to Three Rivers Sta- dium for the home opener of the 1980 season, they had every reason to feel optimistic about the Pirates and Pittsburgh sports in general. In the 1970s, their Pirates had captured six divisional titles, two National League pennants, and two World Series championships. Their Steelers, after decades of futility, had won four Super Bowls in the 1970s, while the University of Pittsburgh Panthers led by Heisman Trophy winner Tony Dorsett added to the excitement by winning a collegiate national championship in football. There was no reason for Pittsburgh sports fans to doubt that the 1980s would bring even more titles to the City of Champions. After the “We Are Family” Pirates, led by Willie Stargell, won the 1979 World Series, the ballclub’s goals for 1980 were “Two in a Row and Two Million Fans.”1 If the Pirates repeated as World Series champions, it would mark the first time that a Pirates team had accomplished that feat in franchise history. If two million fans came out to Three Rivers Stadium to see the Pirates win back-to-back World Series titles, it would 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. break the attendance record of 1,705,828, set at Forbes Field during the improbable championship season of 1960. The offseason after the 1979 World Series victory was a whirlwind of awards and honors, highlighted by World Series Most Valuable Player (MVP) Willie Stargell and Super Bowl MVP Terry Bradshaw of the Steelers appearing on the cover of the December 24, 1979, Sports Illustrated as corecipients of the magazine’s Sportsman of the Year Award. -

Big League Expansion

WEDNESDAY, MAY 1, 1961 With South High winning its fourth straight shutout and North losing to Mira Costa, 4-2, the two Torrance schools are tied for the Bay League baseball lead with 11-3 records. Big League Mira Costa scored four runs in the first inning to beat the Saxons. Costa has a|' 4-8 record. Expansion Dick Foulk, who went eight innings to edge Mira Costa, Smith ...........ir...........11 1-0, a week ago, came back Hawthorn* ......10 Veteran baseball front office executive Bill Veeck' Redondo ........ 6 Monday for an 11-0 whitewash 8»nto Monica , unveiling his proposal for a sweeping realignment of' of Redondo. Dennis RectorlMir* o»u....... 4 the major leagues, submits a plan that place the New hurled two innings of the win. In«"1""x><Vond.y'. ' " Mlr» CosU 4. North 1 York Yankees and New York Mets together in one divi The Spartans got their first South H. RndondoO sion, the Chicago White "Sox and Chicago Cubs together two runs in the first frame Hawthorn* 9, B*nU MnnJ<m 4 Today'* damn In another, and the Los Angeles Dodgers, Anahcim and picked up five more in South «t 8*1**. Monlc* the third. Infrlewood at North Angels, San Francisco Giants and Oakland Athlet'cs in Steve Shrader cleaned the yet another division composed entirely of West Ccast bases with a triple as part of teams. the 5-run spree. Elaborating on his ideas in an article in the current MikeHrehor'and Brent Bar- Triple by ron both had two hits for the Issue of Sport Magazine, Veeck proposes the following Spartans. -

Long Gone Reminder

ARTI FACT LONG GONE REMINDER IN THE REVERED TRADITION OF NEIGHBORHOOD BALLPARKS, PITTSBURGH’S FORBES FIELD WAS ONE OF THE GREATS. Built in 1909, it was among the first made of concrete and steel, signaling the end of the old wooden stadiums. In a city known for its work ethic, Forbes Field bespoke a serious approach to leisure. The exterior was elaborate, the outfield vast. A review of the time stated, “For architectural beauty, imposing size, solid construction, and public comfort and convenience, it has not its superior in the world.” THE STADIUM WAS HOME TO THE PITTSBURGH PIRATES FROM 1909 TO 1970. In the sum- mer of 1921, it was the site of the first radio broadcast of a major league game. It was here that Babe Ruth hit his final home run. In later decades, a new generation of fans thrilled to the heroics of Roberto Clemente and his mates; Forbes was the scene of one of the game’s immortal moments, when the Pirates’ Bill Mazeroski hit a home run to win the thrilling 1960 World Series in game seven against the hated Yankees. The University of Pittsburgh’s towering Cathedral of Learning served as an observation deck for fans on the outside (pictured). AT THE DAWN OF THE 1970S, SEISMIC CHANGES IN THE STEEL INDUSTRY WERE UNDERWAY, and Pittsburgh faced an uncertain future. Almost as a ritual goodbye to the past, Forbes Field was demolished, replaced with a high tech arena with Astroturf at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. Three Rivers Stadium was part of the multi-purpose megastadium wave of the 1970s. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

University of Nebraska Press Sports

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS SPORTS nebraskapress.unl.edu | unpblog.com I CONTENTS NEW & SELECTED BACKLIST 1 Baseball 12 Sports Literature 14 Basketball 18 Black Americans in Sports History 20 Women in Sports 22 Football 24 Golf 26 Hockey 27 Soccer 28 Other Sports 30 Outdoor Recreation 32 Sports for Scholars 34 Sports, Media, and Society series FOR SUBMISSION INQUIRIES, CONTACT: ROB TAYLOR Senior Acquisitions Editor [email protected] SAVE 40% ON ALL BOOKS IN THIS CATALOG BY nebraskapress.unl.edu USING DISCOUNT CODE 6SP21 Cover credit: Courtesy of Pittsburgh Pirates II UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS BASEBALL BASEBALL COBRA “Dave Parker played hard and he lived hard. Cobra brings us on a unique, fantastic A Life of Baseball and Brotherhood journey back to that time of bold, brash, and DAVE PARKER AND DAVE JORDAN styling ballplayers. He reveals in relentless Cobra is a candid look at Dave Parker, one detail who he really was and, in so doing, of the biggest and most formidable baseball who we all really were.”—Dave Winfield players at the peak of Black participation “Dave Parker’s autobiography takes us back in the sport during the late 1970s and early to the time when ballplayers still smoked 1980s. Parker overcame near-crippling cigarettes, when stadiums were multiuse injury, tragedy, and life events to become mammoth bowls, when Astroturf wrecked the highest-paid player in the major leagues. knees with abandon, and when Blacks had Through a career and a life noted by their largest presence on the field in the achievement, wealth, and deep friendships game’s history. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

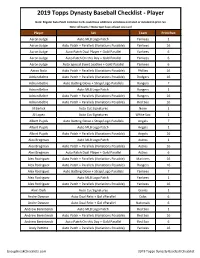

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

Sports Authority, Gold Glove Award Winners and Councilmember Cate Inspire Youth to Swing for the Fences

Contact: Rebecca Kelley [email protected] C: (619) 384-5269 Date: February 18, 2016 SPORTS AUTHORITY, GOLD GLOVE AWARD WINNERS AND COUNCILMEMBER CATE INSPIRE YOUTH TO SWING FOR THE FENCES San Diego, CA: To kick off the baseball season, Sports Authority is partnering with Clairemont Hilltoppers Little League and the Toby Wells YMCA for its annual Baseball Field Day Clinics at Cadman Park this Saturday, February 20th, 2016. Beginning at 9:00 a.m., 250 San Diego youth, including twenty (20) Toby Wells YMCA youth, ages eleven through fourteen, will take part in free, educational clinics and exercises focused on key infield, outfield, pitching, hitting and agility fundamentals. “The City of San Diego is honored to recognize Sports Authority with a City of San Diego proclamation for their philanthropic efforts and contributions to expanding America’s Favorite Pastime,” per Councilmember Chris Cate. “I am extremely pleased that Sports Authority chose families in District 6 to be the recipients of donors’ time, talent and treasures.” “Sports Authority is one of the nation’s largest full-line sporting goods retailers dedicated to providing customers with great values and great brands. We have nine locations in San Diego county and promote active, healthy living for all members of the community,” stated Katie Feingold, Sports Authority. “Thanks to the generosity of Sports Authority and its partners, twenty (20) YMCA youth will receive a shopping spree at the Sports Authority on Balboa Avenue,” said Siddhartha Vivek, YMCA of San Diego County. WHAT: Sports Authority Baseball Field Day WHERE: Cadman Park, 4280 Avati Drive, San Diego, CA 92117 WHEN: Saturday, February 20th, 2016 | 9:00 a.m. -

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.Com

Atlanta Braves Clippings Wednesday, May 6, 2020 Braves.com Braves' Top 5 center fielders: Bowman's take By Mark Bowman No one loves a good debate quite like baseball fans, and with that in mind, we asked each of our beat reporters to rank the top five players by position in the history of their franchise, based on their career while playing for that club. These rankings are for fun and debate purposes only … if you don’t agree with the order, participate in the Twitter poll to vote for your favorite at this position. Here is Mark Bowman’s ranking of the top 5 center fielders in Braves history. Next week: Right fielders. 1. Andruw Jones, 1996-2007 Key fact: Stands with Roberto Clemente, Willie Mays and Ichiro Suzuki as the only outfielders to win 10 consecutive Gold Glove Awards The 60.9 bWAR (Baseball Reference’s WAR model) Andruw Jones produced during his 11 full seasons (1997-2007) with Atlanta ranked third in the Majors, trailing only Alex Rodriguez (85.7) and Barry Bonds (79.2). Chipper Jones was fourth at 58.9. Within this span, the Braves center fielder led all Major Leaguers with a 26.7 Defensive bWAR. Hall of Fame catcher Ivan Rodriguez ranked second with 16.5. The next closest outfielder was Mike Cameron (9.6). Along with establishing himself as one of the greatest defensive outfielders baseball has ever seen during his time with Atlanta, Jones became one of the best power hitters in Braves history. He ranks fourth in franchise history with 368 homers, and he set the club’s single-season record with 51 homers in 2005. -

VMI Architectural Preservation Master Plan

Preservation Master Plan Virginia Military Institute Lexington, Virginia PREPARED BY: JOHN MILNER ASSOCIATES, INC. West Chester, Pennsylvania Kimberly Baptiste, MUP Krista Schneider, ASLA Lori Aument Clare Adams, ASLA Jacky Taylor FINAL REPORT – JANUARY 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Preservation Master Plan Virginia Military Institute The funding for the preparation of the Preservation Master Plan for Virginia Military Institute was provided by a generous grant from: The Getty Foundation Campus Heritage Grant Program Los Angeles, California Throughout the course of the planning process, John Milner Associates, Inc. was supported and assisted by many individuals who gave generously of their time and knowledge to contribute to the successful development of the Preservation Master Plan. Special thanks and acknowledgement are extended to: VMI ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS • COL Keith Gibson, Director of VMI Museum Operations and Preservation Officer, Chair • COL Bill Badgett, Professor of Fine Arts and Architecture • COL Tom Davis, Professor of History • COL Tim Hodges, Professor of Engineering • LTC Dale Brown, Director of Construction • LTC Jay Williams, Post Engineer • MAJ Dallas Clark, VMI Planning Officer VMI FACULTY AND STAFF MEMBERS • COL Diane Jacob, Head of Archives and Records • Mr. Rick Parker, VMI Post Draftsman OTHER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • All historic images and photographs included within this report are courtesy of the Virginia Military Institute Archives. • All planning and construction documents reviewed during the course of this project -

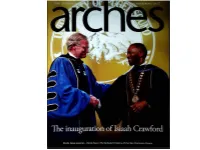

Spring 2017 Arches 5 WS V' : •• Mm

1 a farewell This will be the last issue o/Arches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefton. On the cover: President EmeritusThomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. Conference Women s Basketball Tournament versus Lewis & Clark. After being behind nearly the whole —. game and down by 10 with 3:41 left in the fourth |P^' quarter, the Loggers start chipping away at the lead Visit' and tie the score with a minute to play. On their next possession Jamie Lange '19 gets the ball under the . -oJ hoop, puts it up, and misses. She grabs the rebound, Her second try also misses, but she again gets the : rebound. A third attempt, too, bounces around the rim and out. For the fourth time, Jamie hauls down the rebound. With 10 seconds remaining and two defenders all over her, she muscles up the game winning layup. The crowd, as they say, goes wild. RITE OF SPRING March 18: The annual Puget Sound Women's League flea market fills the field house with bargain-hunting North End neighbors as it has every year since 1968 All proceeds go to student scholarships. photojournal A POST-ELECTRIC PLAY March 4: Associate Professor and Chair of Theatre Arts Sara Freeman '95 directs Anne Washburn's hit play, Mr. Burns, about six people who gather around a fire after a nationwide nuclear plant disaster that has destroyed the country and its electric grid. For comfort they turn to one thing they share: recollections of The Simpsons television series. The incredible costumes and masks you see here were designed by Mishka Navarre, the college's costumer and costume shop supervisor.