Change in the Welsh Marches During the Last Half of the Eleventh Century David M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 August 2014

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2509 PUBLICATION DATE: 05 August 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 26 August 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 19/08/2014 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All post relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Jubilee House Croydon Street Bristol BS5 0DA The public counter at the Bristol office is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Managing online communications and feedback relating to the Welsh visitor attraction experience: apathy and inflexibility in tourism marketing practice? David Huw Thomas, BA, PGCE, PGDIP, MPhil Supervised by: Prof Jill Venus, Dr Conny Matera-Rogers and Dr Nicola Palmer Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David. 2018 i ii DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 iii iv Abstract Understanding of what constitutes a tourism experience has been the focus of increasing attention in academic literature in recent years. For tourism businesses operating in an ever more competitive marketplace, identifying and responding to the needs and wants of their customers, and understanding how the product or consumer experience is created is arguably essential. -

Dearneways 1949-1981

Dearneways Ltd. 1949 - 1981 CONTENTS Dearneways Ltd. - Fleet History 1949 - 1981…………….……………….……………. Page 3 Dearneways Ltd. - Bus Fleet List 1949 - 1981………………………….….….…….…. Page 6 Cover Illustration: No. 86 (LKU86P) was a 1976 Leyland PSU3C/4R with Plaxton 51-seat coachwork. It passed to South Yorkshire PTE in 1981 where it became No. 1086. (Richard Simons). First Published 2016 by The Local Transport History Library. With thanks to John Kaye and Richard Simons for illustrations. © The Local Transport History Library 2016. (www.lthlibrary.org.uk) For personal use only. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise for commercial gain without the express written permission of the publisher. In all cases this notice must remain intact. All rights reserved. PDF-035-1 2 Dearneways Ltd. 1949 - 1981 Dearneways was established in Goldthorpe as late as 1949 when Percy and Maurice Phillipson (father and son) purchased a 1938 Albion Victor to pursue private hire work. In the early part of the next decade the Company secured contract work (including services for the National Coal Board, which was a prominent employer in the area), which resulted in the fleet expanding. In 1956 a tours and excursions licence was granted and several more vehicles were purchased. Dearneways used an attractive blue and cream livery from the start and fleet numbers were introduced around 1954, although not always in sequence. The local firm of Harold Oscroft, who traded as Irene Motors, was taken over in 1960. Two vehicles were included in the deal, neither of which operated for Dearneways. -

CSG Bibliog 24

CASTLE STUDIES: RECENT PUBLICATIONS – 29 (2016) By Dr Gillian Scott with the assistance of Dr John R. Kenyon Introduction Hello and welcome to the latest edition of the CSG annual bibliography, this year containing over 150 references to keep us all busy. I must apologise for the delay in getting the bibliography to members. This volume covers publications up to mid- August of this year and is for the most part written as if to be published last year. Next year’s bibliography (No.30 2017) is already up and running. I seem to have come across several papers this year that could be viewed as on the periphery of our area of interest. For example the papers in the latest Ulster Journal of Archaeology on the forts of the Nine Years War, the various papers in the special edition of Architectural Heritage and Eric Johnson’s paper on moated sites in Medieval Archaeology. I have listed most of these even if inclusion stretches the definition of ‘Castle’ somewhat. It’s a hard thing to define anyway and I’m sure most of you will be interested in these papers. I apologise if you find my decisions regarding inclusion and non-inclusion a bit haphazard, particularly when it comes to the 17th century and so-called ‘Palace’ and ‘Fort’ sites. If these are your particular area of interest you might think that I have missed some items. If so, do let me know. In a similar vein I was contacted this year by Bruce Coplestone-Crow regarding several of his papers over the last few years that haven’t been included in the bibliography. -

Hanes Cudd Eryri Snowdonia's Hidden History

TaflenEinTreftadaethA2_Layout 1 11/09/2014 11:56 Page 1 1 Bryngaer Tre'r Ceiri Hillfort codi yn sgil hynny. hynny. sgil yn codi â chyhoeddi’r wybodaeth neu sy’n neu wybodaeth chyhoeddi’r â Un o’r bryngaerau Oes yr Haearn sydd information. neu am unrhyw fater sy’n gysylltiedig sy’n fater unrhyw am neu wedi goroesi orau yn y wlad. 6 the of publication the of out arising unrhyw beth sydd wedi’i adael allan, adael wedi’i sydd beth unrhyw matter in any way connected with or with connected way any in matter gamgymeriad, anghywirdeb neu anghywirdeb gamgymeriad, One of the best preserved Iron Age any for or omissions, or inaccuracies atebolrwydd am unrhyw am atebolrwydd hillforts in the country. 7 errors, any for whatsoever y cyhoeddwyr dderbyn unrhyw dderbyn cyhoeddwyr y the publishers can accept no liability no accept can publishers the cywirdeb yn y cyhoeddiad hwn, ni all ni hwn, cyhoeddiad y yn cywirdeb 43 publication, this in accuracy ensure Er y gwnaed pob ymdrech i sicrhau i ymdrech pob gwnaed y Er 40 15 to made been has effort every Whilst Llanaelhaearn © Gwynedd Council, 2014 Council, Gwynedd © SH 373446 19 48 2014. Gwynedd, Cyngor © Map AO / OS Map 123 4 47 P 27 28 9 www.snowdoniaheritage.info 2 Siambr Gladdu Dyffryn Ardudwy Burial Tomb 38 11 website our through discovered be can sites more Many 3 Siambr gladdu Neolithig ddwbl a gaiff ei 41 hadnabod fel cromlech borth. Mae’n cael Park. National Snowdonia and ei hystyried yn un o’r enghreifftiau Conwy Gwynedd, across tourism promoting to approach cynharaf o’i bath yn Ynysoedd Prydain. -

IV. the Cantrefs of Morgannwg

; THE TRIBAL DIVISIONS OF WALES, 273 Garth Bryngi is Dewi's honourable hill, CHAP. And Trallwng Cynfyn above the meadows VIII. Llanfaes the lofty—no breath of war shall touch it, No host shall disturb the churchmen of Llywel.^si It may not be amiss to recall the fact that these posses- sions of St. David's brought here in the twelfth century, to re- side at Llandduw as Archdeacon of Brecon, a scholar of Penfro who did much to preserve for future ages the traditions of his adopted country. Giraldus will not admit the claim of any region in Wales to rival his beloved Dyfed, but he is nevertheless hearty in his commendation of the sheltered vales, the teeming rivers and the well-stocked pastures of Brycheiniog.^^^ IV. The Cantrefs of Morgannwg. The well-sunned plains which, from the mouth of the Tawe to that of the Wye, skirt the northern shore of the Bristol Channel enjoy a mild and genial climate and have from the earliest times been the seat of important settlements. Roman civilisation gained a firm foothold in the district, as may be seen from its remains at Cardiff, Caerleon and Caerwent. Monastic centres of the first rank were established here, at Llanilltud, Llancarfan and Llandaff, during the age of early Christian en- thusiasm. Politically, too, the region stood apart from the rest of South Wales, in virtue, it may be, of the strength of the old Silurian traditions, and it maintained, through many vicissitudes, its independence under its own princes until the eve of the Norman Conquest. -

Cymmrodorion Vol 25.Indd

8 THE FAMILY OF L’ESTRANGE AND THE CONQUEST OF WALES1 The Rt Hon The Lord Crickhowell PC Abstract The L’Estrange family were important Marcher lords of Wales from the twelfth century to the Acts of Union in the sixteenth century. Originating in Brittany, the family made their home on the Welsh borders and were key landowners in Shropshire where they owned a number of castles including Knockin. This lecture looks at the service of several generations of the family to the English Crown in the thirteenth century, leading up to the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1282. With its practice of intermarriage with noble Welsh families, the dynasty of L’Estrange exemplifies the hybrid nature of Marcher society in the Middle Ages. Two points by way of introduction: the first to explain that what follows is taken from my book, The Rivers Join.2 This was a family history written for the family. It describes how two rivers joined when Ann and I married. Among the earliest tributaries traced are those of my Prichard and Thomas ancestors in Wales at about the time of the Norman Conquest; and on my wife’s side the river representing the L’Estranges, rising in Brittany, flowing first through Norfolk and then roaring through the Marches to Wales with destructive force. My second point is to make clear that I will not repeat all the acknowledgements made in the book, except to say that I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the late Winston Guthrie Jones QC, the author of the paper which provided much of the material for this lecture. -

Coridor-Yr-M4-O-Amgylch-Casnewydd

PROSIECT CORIDOR YR M4 O AMGYLCH CASNEWYDD THE M4 CORRIDOR AROUND NEWPORT PROJECT Malpas Llandifog/ Twneli Caerllion/ Caerleon Llandevaud B Brynglas/ 4 A 2 3 NCN 4 4 Newidiadau Arfaethedig i 6 9 6 Brynglas 44 7 Drefniant Mynediad/ A N tunnels C Proposed Access Changes 48 N Pontymister A 4 (! M4 C25/ J25 6 0m M4 C24/ J24 M4 C26/ J26 2 p h 4 h (! (! p 0 Llanfarthin/ Sir Fynwy/ / 0m 4 u A th 6 70 M4 Llanmartin Monmouthshire ar m Pr sb d ph Ex ese Gorsaf y Ty-Du/ do ifie isti nn ild ss h ng ol i Rogerstone A la p M4 'w A i'w ec 0m to ild Station ol R 7 Sain Silian/ be do nn be Re sba Saint-y-brid/ e to St. Julians cla rth res 4 ss u/ St Brides P M 6 Underwood ifi 9 ed 4 ng 5 Ardal Gadwraeth B M ti 4 Netherwent 4 is 5 x B Llanfihangel Rogiet/ 9 E 7 Tanbont 1 23 Llanfihangel Rogiet B4 'St Brides Road' Tanbont Conservation Area t/ Underbridge en Gwasanaethau 'Rockfield Lane' w ow Gorsaf Casnewydd/ Trosbont -G st Underbridge as p Traffordd/ I G he Newport Station C 4 'Knollbury Lane' o N Motorway T Overbridge N C nol/ C N Services M4 C23/ sen N Cyngor Dinas Casnewydd M48 Pre 4 Llanwern J23/ M48 48 Wilcrick sting M 45 Exi B42 Newport City Council Darperir troedffordd/llwybr beiciau ar hyd Newport Road/ M4 C27/ J27 M4 C23A/ J23A Llanfihangel Casnewydd/ Footpath/ Cycleway Provided Along Newport Road (! Gorsaf Pheilffordd Cyffordd Twnnel Hafren/ A (! 468 Ty-Du/ Parcio a Theithio Arfaethedig Trosbont Rogiet/ Severn Tunnel Junction Railway Station Newport B4245 Grorsaf Llanwern/ Trefesgob/ 'Newport Road' Rogiet Rogerstone 4 Proposed Llanwern Overbridge -

Listed Buildings Detailled Descriptions

Community Langstone Record No. 2903 Name Thatched Cottage Grade II Date Listed 3/3/52 Post Code Last Amended 12/19/95 Street Number Street Side Grid Ref 336900 188900 Formerly Listed As Location Located approx 2km S of Langstone village, and approx 1km N of Llanwern village. Set on the E side of the road within 2.5 acres of garden. History Cottage built in 1907 in vernacular style. Said to be by Lutyens and his assistant Oswald Milne. The house was commissioned by Lord Rhondda owner of nearby Pencoed Castle for his niece, Charlotte Haig, daughter of Earl Haig. The gardens are said to have been laid out by Gertrude Jekyll, under restoration at the time of survey (September 1995) Exterior Two storey cottage. Reed thatched roof with decorative blocked ridge. Elevations of coursed rubble with some random use of terracotta tile. "E" plan. Picturesque cottage composition, multi-paned casement windows and painted planked timber doors. Two axial ashlar chimneys, one lateral, large red brick rising from ashlar base adjoining front door with pots. Crest on lateral chimney stack adjacent to front door presumably that of the Haig family. The second chimney is constructed of coursed rubble with pots. To the left hand side of the front elevation there is a catslide roof with a small pair of casements and boarded door. Design incorporates gabled and hipped ranges and pent roof dormers. Interior Simple cottage interior, recently modernised. Planked doors to ground floor. Large "inglenook" style fireplace with oak mantle shelf to principal reception room, with simple plaster border to ceiling. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

View the Manual

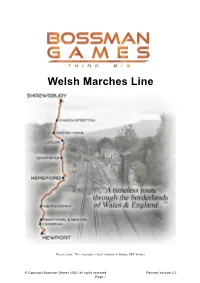

Welsh Marches Line Please note: This manual is best viewed in Adobe PDF Viewer © Copyright Bossman Games 2020, all rights reserved Release Version 2.0 Page 1 Train Simulator – Welsh Marches Line 1 ROUTE HISTORY & BACKGROUND..............................................................................4 2 ROUTE MAP................................................................................................................ 5 3 ROLLING STOCK.........................................................................................................6 3.1 Class 175 (DMSL, MSL).............................................................................................................6 3.2 Class 66 – Maroon & Gold livery.............................................................................................6 3.3 Class 70 – Green & Yellow livery............................................................................................7 3.4 Class 47/8 – Bossman Railways livery...................................................................................7 3.5 Class 43/High Speed Train – Green livery.............................................................................8 3.6 Wagons.......................................................................................................................................8 3.7 Coaches.....................................................................................................................................8 4 CLASS 175................................................................................................................. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal .