Bear and Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equifest 2017

EQUIFEST 2017 Class R1 Preparing for the Evening Performance - Lead Rein Class R2 Preparing for the Evening Performance - First Ridden Class R3 Preparing for the Evening Performance - Open Ponies Class R4 Preparing for the Evening Performance - Open Horse Class I5 In Hand Best Condition 1,2,3 years 1st & ch Springwater Guillot Miss L Oughton-Auker 2nd Wellbrow Harvey Mr Ricky Jones 3rd Moelgarnedd Odette Miss V Hargreaves 4th Banroc Golden Rose Mrs H Kibble 5th Stanray Jay James Miss Emma Stares 6th Dalak Jak A Doodle Mrs L Cartner Class I6 In Hand Best Condition 4 Years & Over 1st & res Oxton Charisma Sophie Cartmell 2nd Heniarth Norman Stanley Fletcher Mrs Margaret Cousin 3rd The Wee Man Christine Heady 4th Llanai Tiago Natasha Walter 5th Sheriff Woddy Miss L Burbidge 6th Lotuspoint Commander Mrs K J Garrett 7th Black Diamond Miss K Watson 8th Glenfyne Sapphire Mrs Holly Charnock 9th Lucky Luciano Miss D Kalwa 10th Jananda Party Suprise Miss Ellie Sutton Class I7 In Hand Part Breds 1,2,3 years old 1st & res Brindlebrooks Serendipity Miss N Timson 2nd Cartigan Misty Morning Mrs Jean Cartwright 3rd Ashlea Little Prince Mrs A Miller 4th Brindlebrooks Unnanounced Miss N Timson Class I8 In Hand Part Bred 4 years old & over 1st & ch Stanley Grange Sea Shells Mrs Leeanne Crowe 2nd Treworgan Black Cat Miss Sam Loveridge 3rd Barkway Water Lily Ms Debbie Foster 4th Melin Moldavite Emma Peel 5th Oxton Charisma Sophie Cartmell 6th Grindles Zodiac Miss Charlotte Hall & Miss Sophie Hall 7th Bridgehill Crackerjack Mrs Karen Clarke 8th Lucky Luciano -

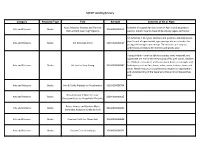

SCECP Lending Library

SCECP Lending Library Category Resource Type Title Barcode Contents of Kit or Note April: Patterns, Projects and Plans to A wealth of support for the month of April including posters, Arts and Patterns Books 33104000000019 Perk up Early Learning Programs awards, bulletin boards, basic skills activity pages, and more! Art Activities A to Z gives teachers and parents a detailed lesson plan format of open-ended, age- appropriate art activities for Arts and Patterns Books Art Activities A to Z 33104000000027 young children ages one and up. The activities are easy-to- understand and follow for children and adults alike. Young children have the ability to create, view, interpret, and appreciate art. Art for the Very Young offers over 50 art activities for children to create art and learn about basic art concepts and Arts and Patterns Books Art for the Very Young 33104000008947 techniques, such as line, shape, color, space, texture, form, and value. Watch how your young learners acquire an appreciation and understanding of the featured artists and techniques they use! Arts and Patterns Books Arts & Crafts Projects for Preschoolers 33104000008764 Beautiful Junk II: More Creative Arts and Patterns Books 33104000000035 Classroom Uses for Recyclable Materials Better Homes and Garden: More Arts and Patterns Books 33104000008863 Incredibly Awesome Crafts for Kids Arts and Patterns Books Creative Crafts for Clever Kids 33104000008848 Arts and Patterns Books Cut and Create! Holidays 33104000008731 Category Resource Type Title Barcode Contents of Kit -

Interview with Elina Psykou

INTERVIEW WITH ELINA PSYKOU DIRECTOR OF “SON OF SOFIA” A FEATURE FILM SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES JUNE 2020 BY KARIN SCHIEFER TWO OLYMPIC GAMES ARE THE TEMPORAL REFER- GAMES. THIS IS THE FIRST HINT OF SOMETHING ENCE POINTS OF “SON OF SOFIA”: THE ONE IN ATH- THAT COMES OUT AS A VERY CENTRAL ELEMENT ENS WHERE THE STORY TAKES PLACE AND THE 1980 IN YOUR STORYTELLING: ANIMALS. THEY APPEAR GAMES IN MOSCOW. YOU SEEM TO REFER TO THE SYM- AS MASKS, COSTUMES, FANTASIES OR TOYS (AS A BOLIC MEANING OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES, WITH THE WONDERFUL OBJECT OF PROJECTIONS). CAN YOU CASE OF ATHENS BEING THE CRADLE OF THE GAMES TELL US MORE ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE YOU GAVE AND THE CASE OF MOSCOW RATHER AS A MEANS TO ANIMALS AND WHY YOU CHOSE ELEMENTS OF OF DEMONSTRATING THE POWER OF THE REGIME. THE FAIRY TALE AS A GENRE? WHY DID YOU SET YOUR STORY IN THE EARLY 2000s? Fairy tales are full of animals and very often they are The Olympic Games in Moscow took place in 1980, a used to represent the good and the bad – the bad wolf, couple of years before the collapse of the Soviet Union; the good bear. For children, animals offer a first access the Athens Olympics was in 2004, a few years before the to the symbols of life and to a lot of stereotypes and, collapse of the Greek economy. I take this as an interest- as they discover this, also to the world of adults. I de- ing metaphor and parallel. I used the Olympic Games cided to use the animals since a child’s imagination is as a metaphor for the life of Misha, the young boy who full of them and adults use them to introduce children is one of my protagonists. -

Examining the Changing Use of the Bear As a Symbol of Russia

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title The “Forward Russia” Flag: Examining the Changing Use of the Bear as a Symbol of Russia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xz8x2zc Journal Raven: A Journal of Vexillology, 19 ISSN 1071-0043 Author Platoff, Anne M. Publication Date 2012 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The “Forward Russia” Flag 99 The “Forward Russia” Flag: Examining the Changing Use of the Bear as a Symbol of Russia Anne M. Platoff Introduction Viewers of international sporting events have become accustomed to seeing informal sporting flags waved by citizens of various countries. The most famil- iar of these flags, of course, are the “Boxing Kangaroo” flag used to represent Australia and the “Fighting Kiwi” flag used by fans from New Zealand. Both of these flags have become common at the Olympic Games when athletes from those nations compete. Recently a new flag of this type has been displayed at international soccer matches and the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics. Unlike the Kangaroo and Kiwi flags, this new flag has been constructed using a defaced national flag, the Russian tricolor flag of white, blue, and red horizontal stripes, readopted as the flag of the Russian Federation after the breakup of the Soviet Union. A number of variations of the flag design have been used, but all of them contain two elements: the Russian text Vperëd Rossiia, which means “Forward Russia”, and a bear which appears to be break- ing its way out of the flag. -

Treaty Advances Make the Slam Without the Diamond ► Pass 2 ♦ Pass Played a Diamond, but West Showed 1986 CHEW CEL$Prrry SEDAN ► Pass 3 NT Out

24—MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, June 1, 1990 I CARS CARS MOTORCYCLES/ Astrograph FOR SALE MOTORCYCLES/ L ^ FOR SALE [2 2 J MOPEDS MOPEDS where you can't make a move until BLUE TEAAPO-1987. Air DODGE - 1986. ‘150’, 318 KAWAKSAKI-1988 KX the finger of blame at them. someone upon whom you're depending conditioning, 50K. CID, autamatic, bed 250. Runs gaad. $1850ar ^ o u r does. Your wail might be in vain. CAPRICORN (Dec. 22-Jan. 19) Several Good condition. Runs liner, faal bax, 50K, Motorcycle Insurance best otter. LEO (July 23-Aug. 22) Be extremely goals that are of importance to you to well. $4,900. Coll 643- $5500. 742-8669. Many com^ve companies J birthday careful in your conversations today that day might not be of equal significance 9382. ______________ to persons with whom you'll be in Call Fa Free Quote you do not put someone down in order CADILLAC-1979 Coupe to make yourself look good. It could volved. This could cause everyone to Automobile Associates WANTED TO pull in a different direction. DeVllle. New point, raTRUCKS/VANS June 2,1990 have the opposite affect of what you Cleon, runs greot. Must ofVemon BUY/TRADE desire. AQUARIUS (Jan. 20-Feb. 19) It’s best sell. $3,200 or best otter. FOR SALE fi7A.09i;A Any character building situations to VIRGO (Aug. 23-Sept. 22) In your com not to make any promises today that 635-7391. which you're exposed in the year ahead, mercial dealings today, be open and you're not absolutely certain you can FORD-1984 Van. -

A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot

A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT by Seth Benedict Graham BA, University of Texas, 1990 MA, University of Texas, 1994 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2003 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Seth Benedict Graham It was defended on September 8, 2003 and approved by Helena Goscilo Mark Lipovetsky Colin MacCabe Vladimir Padunov Nancy Condee Dissertation Director ii Copyright by Seth Graham 2003 iii A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT Seth Benedict Graham, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2003 This is a study of the cultural significance and generic specificity of the Russo-Soviet joke (in Russian, anekdot [pl. anekdoty]). My work departs from previous analyses by locating the genre’s quintessence not in its formal properties, thematic taxonomy, or structural evolution, but in the essential links and productive contradictions between the anekdot and other texts and genres of Russo-Soviet culture. The anekdot’s defining intertextuality is prominent across a broad range of cycles, including those based on popular film and television narratives, political anekdoty, and other cycles that draw on more abstract discursive material. Central to my analysis is the genre’s capacity for reflexivity in various senses, including generic self-reference (anekdoty about anekdoty), ethnic self-reference (anekdoty about Russians and Russian-ness), and critical reference to the nature and practice of verbal signification in more or less implicit ways. The analytical and theoretical emphasis of the dissertation is on the years 1961—86, incorporating the Stagnation period plus additional years that are significant in the genre’s history. -

Sporting & Collectors' Sale

SPORTING & COLLECTORS’ SALE Wednesday 25th & Thursday 26th February 2015 OKEHAMPTON STREET EXETER Sporting & Collectors’ Sale For Sale by Auction at St. Edmund’s Court Okehampton Street Exeter EX4 1DU Wednesday 25th February 2015 and Thursday 26th February 2015 Commencing at 10.00am each day On View Saturday 21st February 9am - 12 noon Monday 23rd February 9am - 5.15pm Tuesday 24th February 9am - 5.15pm on morning of sale from 9am Catalogue £5.00 (£7.00 by post) W: www.bhandl.co.uk E: [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @BHandL SPORTING & COLLECTORS’ SALE CATEGORIES DAY ONE Lots CARS, etc. 1- 4 CERAMICS AND GLASS 5-8 SILVER & METALWARES 9-16 HUNTING AND EQUESTRIAN 17-44 TAXIDERMY 45-56 SHOOTING & RELATED 57-73 AIR RIFLES & PISTOLS 74-107 SPORTING GUNS 108-113 GUNS – OTHER CALIBRES 114-171 EDGED WEAPONS 172-350 MEDALS & MILITARIA 351-507 EMERGENCY SERVICES 508-590 FISHING 591-621 OTHER SPORTS (RUGBY, FOOTBALL, TENNIS ETC) 622-638 TRANSPORT AND MOTORING 639-717 PRINTS 718-732 WATERCOLOURS 733-746 MARITIME PICTURES 747-750 MARITIME FITTINGS 751 INSTRUMENTS and NAVIGATION 752-754 SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 755-759 MARINE COLLECTABLES 760-762 MODELS 763-764 **** END OF DAY ONE**** DAY TWO STAMPS 765-828 POSTCARDS & CIGARETTE CARDS 829-896 COINS 897-904 TEXTILES 905-924 DOLLS & TEDDY BEARS 925-996 DIECASTS 997-1091 OO/HO GAUGE RAILWAYS 1092-1166 O GAUGE RAILWAYS 1167-1198 LARGER GAUGE RAILWAY 1199-1200 FULL SIZE RAILWAYS 1201-1210 TOYS & COLLECTABLES 1211-1299 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS 1300-1313 DAY 1 - Wednesday 25th February 2015 Sale commences at 10am. -

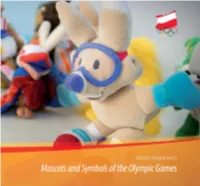

Olympic Mascots

1 Olympic Mascots Mascots appeared in sport in the 1920s. Among the Championships in 1966, clever “Willie” became the mas- fi rst of them were personal mascots, which were carried cot, and in 1974 footballers were accompanied by two by athletes who believed in their magical power. Their mascots, “Tips and Taps”, which had the appearance of presence at sports arenas was supposed to ensure ath- swashbuckling rascals. letes’ fortune and victory. When mascots appeared at the Olympic Games they The trend towards mascots appeared both among made a staggering career in terms of popularity, artistic male and female athletes, independently of age or sports; vision and marketing, while the faith in mascots’ magical it was, however, seen mostly among athletes practicing powers gained a secret dimension. sports, in which the eff ect of performing an exercise is a The fi rst unoffi cial Olympic mascot was a live mutt matter of the judge’s subjective assessment. called “Smoky” which appeared during the Games of the The diversity of mascots is enormous. Mascots are, X Olympiad in Los Angeles (1932). “Smoky” had a dark most often, objects which have the character of chil- curly coat, a long trunk, short paws, protruding ears and dren’s toys: dolls, plushy animals (teddy bears, elephants, a rolled up tail. A white cape covered the back of the dog kitties, doggies, donkeys, fairytale characters), pebbles, with the emblem of the fi ve Olympic rings and the in- shells, horseshoes, clothing articles (ornaments or parts scription “Mascot”. of a favorite outfi t: caps, T-shirts). -

Get Kindle \\ Fictional Bears

PQCJL8HZRPDC « eBook \\ Fictional bears Fictional bears Filesize: 9.61 MB Reviews Excellent electronic book and helpful one. I could comprehended everything out of this published e book. I discovered this pdf from my i and dad suggested this book to discover. (Dr. Daphnee Homenick II) DISCLAIMER | DMCA OUZKRUERFP0D « eBook \ Fictional bears FICTIONAL BEARS Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 101. Chapters: Beorn, Humphrey B. Bear, Fozzie Bear, Disney's Adventures of the Gummi Bears, List of Care Bear characters, Care Bears, Winnie-the-Pooh, Shardik, List of fictional bears, Smokey Bear, The Story of the Three Bears, Rupert Bear, Berenstain Bears, The Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin, Seekers, CB Bears, Paddington Bear, Yogi Bear, Brother Bear, Bamse, Help! It's the Hair Bear Bunch!, Special Agent Oso, Owlbear, SuperTed, Naughty Bear, Paw Paws, Pedobear, The Yogi Bear Show, Bear in the Big Blue House, Mary Plain, Colargol, The Beary Family, The Bear That Wasn't, Rilakkuma, Boku wa Kuma, Humphrey the Bear, Chucklewood Critters, The Brown Bear of Norway, Oski, Oliver B. Bumble, C Bear and Jamal, Nev T. Bear, Rasmus Klump, Boo-Boo Bear, Barney Bear, The Bear family, Baloo, Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear, Fatty Bear, The Further Adventures of SuperTed, The Hillbilly Bears, Demon Bear, De Bereboot, Christmas on Bear Mountain, Bio the Bear, Gentle Ben, Cookie Bear, The Brown Bear of the Green Glen, Sugar Bear, Hamm's Beer bear, Kissyfur, Misha, Bungle, Corduroy, Bauk, Snuggle, Joe Bruin, George and Junior, The Cat on the Dovrefjell, Mors lilla Olle, Fatso the Bear, Windy & Breezy, The Bear Went Over the Mountain, Little Bear, Teddy Edward, Bobo the Bear, Buster the Amazing Bear, Tottles the Bear, Dörmögo Dömötör, Broxi Bear, Old Ben. -

The Kennel Club Registration Printed: 22/08/2014 14:37:13 PRA (Cord1) Tests August 2014 Page: 1 of 75

Report: r_dna_test The Kennel Club Registration Printed: 22/08/2014 14:37:13 PRA (cord1) Tests August 2014 Page: 1 of 75 Below is a list of Kennel Club registered dogs of the breed specified above, together with their sire and dam, giving the date that they were DNA tested for the recessively inherited disease specified above. The result of the test can be either CLEAR (no copies of the mutant gene), CARRIER (one copy of the mutant gene) or AFFECTED (two copies of the mutant gene). Note that the progeny of a clear sire and clear dam will also be clear (hereditarily clear), and the progeny of two hereditarily clear, or one hereditarily clear and one tested clear dog will also be hereditarily clear. Further information on this scheme can be obtained from The Kennel Club Dog Name Reg/Stud No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Result BREED: DACHSHUND (MINIATURE LONG-HAIRED) AFRICANDAWNS BLAC TREACLE WITH LIRIC AJ00858501 24/11/2007 B BRONIA ROYAL FLUSH AT AFRICANDAWNS AFRICANDAWNS MINI PRELUDE 24/11/2007 HRDY CLEAR AFRICANDAWNS BLAC TROUBLE AJ00858502 24/11/2007 B BRONIA ROYAL FLUSH AT AFRICANDAWNS AFRICANDAWNS MINI PRELUDE 24/11/2007 HRDY CLEAR AFRICANDAWNS DRUMER GIRL AR02168205 13/05/2014 B LIRIC MR CANDYMAN AMONG AFRICANDAWNS AFRICANDAWNS RED SUSIE 13/05/2014 HRDY CLEAR AFRICANDAWNS DRUMMER BOY AR02168201 13/05/2014 D LIRIC MR CANDYMAN AMONG AFRICANDAWNS AFRICANDAWNS RED SUSIE 13/05/2014 HRDY CLEAR AFRICANDAWNS LITTLE DRUMER AR02168204 13/05/2014 B LIRIC MR CANDYMAN AMONG AFRICANDAWNS AFRICANDAWNS RED SUSIE 13/05/2014 HRDY CLEAR AFRICANDAWNS LITTLE -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Kindle \ Fictional Bears > Download

RINHFDUQDM > Fictional bears « Doc Fictional bears By Source Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 101. Chapters: Beorn, Humphrey B. Bear, Fozzie Bear, Disney's Adventures of the Gummi Bears, List of Care Bear characters, Care Bears, Winnie-the-Pooh, Shardik, List of fictional bears, Smokey Bear, The Story of the Three Bears, Rupert Bear, Berenstain Bears, The Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin, Seekers, CB Bears, Paddington Bear, Yogi Bear, Brother Bear, Bamse, Help! It's the Hair Bear Bunch!, Special Agent Oso, Owlbear, SuperTed, Naughty Bear, Paw Paws, Pedobear, The Yogi Bear Show, Bear in the Big Blue House, Mary Plain, Colargol, The Beary Family, The Bear That Wasn't, Rilakkuma, Boku wa Kuma, Humphrey the Bear, Chucklewood Critters, The Brown Bear of Norway, Oski, Oliver B. Bumble, C Bear and Jamal, Nev T. Bear, Rasmus Klump, Boo-Boo Bear, Barney Bear, The Bear family, Baloo, Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear, Fatty Bear, The Further Adventures of SuperTed, The Hillbilly Bears, Demon Bear, De Bereboot, Christmas on Bear Mountain, Biffo the Bear, Gentle Ben, Cookie Bear, The Brown Bear of the Green Glen, Sugar Bear, Hamm's Beer bear, Kissyfur, Misha, Bungle, Corduroy, Bauk, Snuggle, Joe Bruin, George and Junior, The Cat on the... READ ONLINE [ 5.89 MB ] Reviews The most eective publication i ever go through. It really is writter in simple phrases and not hard to understand. I am just easily will get a satisfaction of looking at a written publication. -- Ila Pfeffer IV This is the greatest book i have got read through till now.