Soapstone in the North Quarries, Products and People 7000 BC – AD 1700

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4634 72Dpi.Pdf (6.278Mb)

Norsk institutt for vannforskning RAPPORT Hovedkontor Sørlandsavdelingen Østlandsavdelingen Vestlandsavdelingen Akvaplan-niva Postboks 173, Kjelsås Televeien 3 Sandvikaveien 41 Nordnesboder 5 0411 Oslo 4879 Grimstad 2312 Ottestad 5005 Bergen 9296 Tromsø Telefon (47) 22 18 51 00 Telefon (47) 37 29 50 55 Telefon (47) 62 57 64 00 Telefon (47) 55 30 22 50 Telefon (47) 77 75 03 00 Telefax (47) 22 18 52 00 Telefax (47) 37 04 45 13 Telefax (47) 62 57 66 53 Telefax (47) 55 30 22 51 Telefax (47) 77 75 03 01 Internet: www.niva.no Tittel Løpenr. (for bestilling) Dato Foreløpig forslag til system for typifisering av norske 4634-2003 10.02.03 ferskvannsforekomster og for beskrivelse av referansetilstand, samt forslag til referansenettverk Prosjektnr. Undernr. Sider Pris 21250 93 Forfatter(e) Fagområde Distribusjon Anne Lyche Solheim, Tom Andersen, Pål Brettum, Lars Erikstad (NINA), Arne Fjellheim (LFI, Stavanger museum), Gunnar Halvorsen (NINA), Trygve Hesthagen (NINA), Eli-Anne Lindstrøm, Geografisk område Trykket Marit Mjelde, Gunnar Raddum (LFI, Univ. i Bergen), Tuomo Norge NIVA Saloranta, Ann-Kristin Schartau (NINA), Torulv Tjomsland og Bjørn Walseng (NINA) Oppdragsgiver(e) Oppdragsreferanse SFT, DN, NVE Sammendrag Innføringen av Rammedirektivet for vann (”Vanndirektivet”) medfører at Norges vannforekomster innen utgangen av 2004 skal inndeles og beskrives etter gitte kriterier. Et av kriteriene er en typeinndeling etter fysiske og kjemiske faktorer. Denne typeinndelingen danner grunnlaget for overvåkning og bestemmelse av økologisk referansetilstand for påvirkede vannforekomster. Vanndirektivet gir valg mellom å bruke en predefinert all-europeisk typologi (”System A”), eller å etablere en nasjonal typologi som forutsettes å gi bedre og mer relevant beskrivelse enn den all-europeiske, og som må inneholde visse obligatoriske elementer (”System B”). -

Flomberegning for Nedre Del Av Arendalsvassdraget

Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Telefon: 22 95 95 95 Middelthunsgate 29 Telefaks: 22 95 90 00 Postboks 5091 Majorstua Internett: www.nve.no 0301 Oslo Flomsonekartprosjektet Flomberegning for nedre del av Arendalsvassdraget Lars-Evan Pettersson 22 2005 DOKUMENT Flomberegning for nedre del av Arendalsvassdraget (019.Z) Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat 2005 Dokument nr 22 - 2005 Flomberegning for nedre del av Arendalsvassdraget (019.Z) Utgitt av: Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Forfatter: Lars-Evan Pettersson Trykk: NVEs hustrykkeri Opplag: 30 Forsidefoto: Flom ved Rygene i 1911 (Foto: NVEs fotoarkiv) ISSN: 1501-2840 Sammendrag: I forbindelse med Flomsonekartprosjektet i NVE er det som grunnlag for vannlinjeberegning og flomsonekartlegging utført flomberegning for et delprosjekt i Arendalsvassdraget. Flomvannføringer med forskjellige gjentaksintervall er beregnet for tre punkter i Nidelva: ved Evenstad, oppstrøms elven fra Rore og ved Rygene. Emneord: Flomberegning, flomvannføring, Nidelva, Arendalsvassdraget Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Middelthuns gate 29 Postboks 5091 Majorstua 0301 OSLO Telefon: 22 95 95 95 Telefaks: 22 95 90 00 Internett: www.nve.no Desember 2005 Innhold Forord..............................................................................................................4 Sammendrag...................................................................................................5 1. Beskrivelse av oppgaven ................................................................6 2. Beskrivelse av vassdraget -

Fiskebiologiske Undersøkelser I Fire Laksevassdrag På Sørlandet

1939 Fiskebiologiske undersøkelser i fire laksevassdrag på Sørlandet Resultater og erfaringer fra utprøving av elektrisk båtfiske Gunnbjørn Bremset, Jon Museth, Eva Marita Ulvan & Randi Saksgård NINAs publikasjoner NINA Rapport Dette er NINAs ordinære rapportering til oppdragsgiver etter gjennomført forsknings-, overvåkings- eller utredningsarbeid. I tillegg vil serien favne mye av instituttets øvrige rapportering, for eksempel fra seminarer og konferanser, resultater av eget forsknings- og utredningsarbeid og litteraturstudier. NINA Rapport kan også utgis på engelsk, som NINA Report. NINA Temahefte Heftene utarbeides etter behov og serien favner svært vidt; fra systematiske bestemmelsesnøkler til informasjon om viktige problemstillinger i samfunnet. Heftene har vanligvis en populærvitenskapelig form med vekt på illustrasjoner. NINA Temahefte kan også utgis på engelsk, som NINA Special Report. NINA Fakta Faktaarkene har som mål å gjøre NINAs forskningsresultater raskt og enkelt tilgjengelig for et større publikum. Faktaarkene gir en kort framstilling av noen av våre viktigste forskningstema. Annen publisering I tillegg til rapporteringen i NINAs egne serier publiserer instituttets ansatte en stor del av sine forskningsresultater i internasjonale vitenskapelige journaler og i populærfaglige bøker og tidsskrifter. Fiskebiologiske undersøkelser i fire laksevassdrag på Sørlandet Resultater og erfaringer fra utprøving av elektrisk båtfiske Gunnbjørn Bremset Jon Museth Eva Marita Ulvan Randi Saksgård Norsk institutt for naturforskning NINA -

Og Sårbarhetsanalyse for Aust-Agder Og Vest-Agder 3

ROS AGDER 2011 Fylkesmannen i Aust-Agder og Fylkesmannen i Vest-Agder Risiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse for Aust-Agder og Vest-Agder 3. mai 2011 1 ROS AGDER 2011 2 ROS AGDER 2011 Forord I embetsoppdraget til fylkesmennene har Direktoratet for samfunnssikkerhet og beredskap (DSB) gitt et pålegg om å utarbeide og holde oppdatert en Fylkesrisiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse (Fylkes ROS- analyse) Det står videre i embetsoppdraget at fylkesmennene skal påse at ROS-analyser som er utarbeidet av myndigheter og virksomheter blir samordnet slik at de bidrar til en oppdatert totaloversikt av risiko og sårbarhet i fylket. Aust-Agder og Vest-Agder er to ganske like fylker når det gjelder risiko- og sårbarhetsforhold og har mange felles regionale myndigheter og virksomheter. Fylkesmennene i Agder har derfor valgt å samarbeide om å utarbeide en ny felles risiko- og sårbarhetsanalyse for Aust- og Vest-Agder, forkortet til ROS Agder. Dette er imidlertid et arbeid som fylkesmennene ikke kan gjøre på egenhånd. Vi har samarbeidet med myndigheter og virksomheter som representerer infrastruktur og samfunnsfunksjoner i fylkene, og som har gitt data og informasjon på aktuelle fagområder. Fylkesmennene tror at en slik overordnet gjennomgang av risiko- og sårbarhetsforhold er et viktig grunnlag for beredskapsplanlegging i etater og kommuner. Vi er takknemlige for at sentrale aktører har bidratt i arbeidet med å utarbeide en felles ROS-analyse for fylkene våre. Vi har valgt en kvalitativ/verbal tilnærming til ROS analysen for Agder. Det vil si at den i stor grad vil være uten bruk av tall på sannsynlighet og konsekvens da vi mener dette vil gi det beste oversiktsbildet over risiko og sårbarhet i fylket. -

Efsetterretninger for SJØFARENDE ETTERRETNINGER

2002 ETTERRETNINGEREfETTERRETNINGER FORFOR SJØFARENDESJØSJØFARENDEs FARENDE Notices to Mariners STATENS KARTVERK Nr 13 SJØ Årgang 133 L.nr. 535 - 593 - Stavanger 15 juli 2002 13/02 342 UTGITT AV SJØKARTVERKET. «Etterretninger for sjøfarende» (Efs) utkommer to ganger månedlig og gir opplysninger om forskjellige forhold som kan være av interesse for sjøfarende. Årlig abonnement koster kr. 500,- og kan bestilles gjennom: Statens kartverk Sjø. Postboks 60, 4001 Stavanger. Telefon 51 85 87 00. Telefax 51 85 87 01. Telefax kartsalget 51 85 87 03 E-post (E-mail): [email protected] Redaksjon Efs: E-post (E-mail): [email protected] Internett: http://www.statkart.no/efs Telefax: 51 85 87 06 Tegning av årlig abonnement etter kalenderårets begynnelse gir rett til å få tilsendt tidligere i året utkomne nummer. Etterretninger for sjøfarende (Efs) i digital form er av Sjøfartsdirektoratet godkjent på lik linje som den analoge Efs og kan nå overføres via E-post (E-mail) som PDF file (Acrobat Reader). Den digitale Efs vil være tilgjengelig for abonnenten ca. 5 dager før papirutgaven foreligger. The «Etterretninger for sjøfarende» (Efs) is also available in digital format as a PDF file sent via e-mail. —————————————————————————————————— Efs /Kartrettelser på Internett. Etterretninger for sjøfarende samt kartrettelser for hvert enkelt kart og båtsportkart serie A - T er tilgjengelig på Internett: http://www.statkart.no/efs/meldingmain.html Internett versjonen av Efs er bare et supplement til den offisielle utgaven. Efs/Chart Correction on Internet. The «Etterretninger for sjøfarende» (Efs) and Chart Correction for each chart (sorted by chart number) and Small Craft Charts Series A - T are available on Internet: http://www.statkart.no/efs/gbindex.html Please note! «Etterretninger for sjøfarende» versions available on Internet cannot replace the officially approved version. -

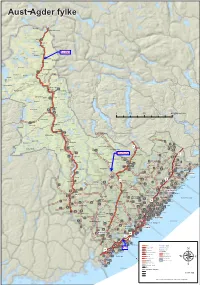

Aust−Agder Fylke

Aust−Agder fylke torhellerfjelli loros fjåen2fjellstove eggine pørsvssE fjelli freiveQRI enevssheii rovden Hartevatnet jørnrotu teinheii Vatndals− letteE vatnet tndlsE skurven dmmene Store Urevatn ferdlen Bykle ferdlsu roslemo fygdeheii Bykleheiane fyklestøyln QRP tvnes rovtn hytt Botsvatn fykle torvssE teinheii egnådlsE torsteinen heii Otra ygnestd QQT otemo uringlevtn qmsø euråhorten juven romme Raudvatnet Valleheiane tvskrdE hytt QQI lle vjomsnuten rddlsE fossu rolteheii Valle ppstd vrtenut QQR QQQ frokkeQQP ykstjørnheii rylestd 0204010 Kilometers ysstd rdvssheii wyklestøyl QQU øtefjell Øyuvsu festelnd eustd Hovatn einshornE W vngeid QPR wjåvsshytt heii qrnheim eiskvæven qjevden tkkedlen ustfjell eustd olhomfjell heii yse korv qukhei Gjøv UI ndnesÅrksø uongsfjell Bygland torrfjellet US VH ndnes qrunnetjørnsu Måvatn RI unndlsE Gjerstad ød UQ tosephsu QPQ freiung UR heii qjøvdlesklnd kåmedl hlePUP RIV QPP wosvld estøl våssen ØsterholtiIV rmreheii eustenå rdehei torlihei ylnd ndån WR QHR fyglnd Nidelva qryting romdrom wo RIU ovdl krsvssu Åmli PUI Gjavnes− UV WI undet Byglands− moen pine T vuvdl Øvre ullingsE PUU WI PUU sndre U rødneø fjorden hei PUS wjåvtn øndeled PUV ÅmliPUR egårshei Tovdalselva vuveik WQ kjeggedl festelihei RIT S QSI vongerk RIS R ivik Vegårshei F wyr IH P Barmen V WP eklnd RIT ÅrdlQPI kliknuten ippelnd fsvtn RIR Q woen isør RII W fås hølemo I qrendi RIQ xonnut øyslnd rovde ndnes Risør RIP iIV frumoen IP pie W RI ehus IHS vget fyglndsE orehei IHI tne ITR WS xipe temhei fjord vuvrk keidmo xelug PUQ IIQ RII QHP qutestdrimmelsyn -

Turreferat Padletur 16 Til 17 Juni

Turreferat Padletur 16. til 17. juni Den planlagte padle,- og fjellturen i Vestheiene måtte avlyses pga mye snø og is i fjellet. Imidlertid var det mange som ønsket seg en tur og planen ble derfor endret slik at vi fikk en padletur i nærliggende strøk. 8 deltakere var påmeldt og alle var klar for helgetur på tross av at værvarselet ikke var særlig lovende. Deltakere var: Dagfinn, Kåre, Inger Johanne, Nils Julian, Rune S, Audun, Ole og Preben. Dette var en fellestur mellom Arendal kajakklubb og Fjellsportgruppa, men siden de fleste hadde egen kajakk var det ikke så mye klubbutstyr som ble brukt. Turen startet i Trevann ved Frolands Verk. Her fikk vi pakket ned i kajakken og heldigvis ble det oppholdsvær da vi startet. Rune fikk blåst i gang turen med sitt nye ”turhorn”! Første del av padleturen gikk over Trevann og ut gjennom kanalen til Nidelva. Deretter fulgte vi Nidelva nedover forbi Oveland, Løddesøl, Messel før vi dro vestover (beklager; til styrbord) ut gjennom kanalen til Rorevann. Lunsj ble inntatt på en liten strand ved Messel. Nedover i Nidelva hadde vi motvind og mange tenkte nok med gru på hvordan det ville bli på Rorevann. Ikke så galt tenkt, for på Rore fik vi skikkelig motvind og gode bølger. Kampen mot vind og bølger ble satt i gang og til slutt kunne vi sige i land på den idylliske sandstranda på Neset. Her fikk vi hvilt og tørket oss litt, nå hadde sola tittet fram! Vårt drikkevann Rore – begrepet ”Storm i et vannglass” Stranda på Neset i Rore har fått en ny betydning. -

Nr. 51 — 2007 SELSKAPET for GRIMSTAD BYS VEL Interessante Bøker for Alle Som Har Tilknytning Til Distriktet

Selskapet for Grimstad Bys Vel Medlemsskrift nr. 51 — 2007 SELSKAPET FOR GRIMSTAD BYS VEL Interessante bøker for alle som har tilknytning til distriktet. Reidar Marmøy: Grimstad på 1900-tallet. Bind 1: 1900-1940. Endelig er den her, den fullstendige historien om Grimstad de første ti-årene av det forrige år- hundret. Denne boken inneholder alt, fra det kommunale styre og stell og næ- ringslivets opp- og nedturer, til utedoer og gatebelysning. Lokalhistorie på sitt beste. Boken er utgitt i 2004, og koster kr. 400,-. Reidar Marmøy: Herbert Waarum - fra plastbåter til bedehus. Denne boken ble gitt ut til Waarums 80-års dag i august 2004. Herbert Waarum er kjent som mannen bak den første norskbygde plastbåten, men her hører vi også om et aktivt liv på andre felt. Foruten et grundig bilde av hovedpersonen Herbert Waarum, byr boken på en god porsjon nyere Grimstad-historie. Kr 100,-. Reidar Marmøy: Grimstad - byen med skjærgården. Historien om byen med skjærgården, om sterke og utholdende personers kamp for byens og innbygger- nes beste, og om kemner Karl O. Knutsons livsverk: Opprettelsen av Selskapet for Grimstad Bys Vel. Boken ble gitt ut til Byselskapets 75-års jubileum i 1997, og koster kr. 100,-. Reidar Marmøy: HÅØY - losenes øy. Boken gir en inngående beskrivelse av lossamfunnet på Håøy. Leseren kan følge slektene der ute og får et klart bilde av forholdene under skiftende ytre vilkår. Kr. 200,-. Nå kr. 100,-. Reidar Marmøy: Et menneske på jorden. Boken om Jens Svendsen Haaø, kjent fisker og predikant fra Håøy. Boken forteller om vennskapet mellom Haaø og Gabriel Scott, og den har med Jens Haaøs etterlatte manuskript om fiske og fiskeredskaper. -

Avd. II Regionale Og Lokale Forskrifter Mv

Nr. 1 - 2003 Side 1 - 206 NORSK LOVTIDEND Avd. II Regionale og lokale forskrifter mv. Nr. 1 Utgitt 14. april 2003 Innhold Side Forskrifter 2000 Feb. 1. Forskrift om snøscooterløyper, Nordreisa (Nr. 1708) ............................................................ 1 Nov. 9. Forskrift om snøscooterløyper, Bardu (Nr. 1709)................................................................... 2 2001 Juni 13. Forskrift om vedtekter for Masfjorden kraftfond, Masfjorden (Nr. 1700) ............................. 3 2002 Des. 17. Forskrift om gebyrregulativ for teknisk sektor, Masfjorden (Nr. 1830)................................. 4 Des. 18. Forskrift om kommunale barnehager, Oslo (Nr. 1831) ........................................................... 4 Des. 19. Forskrift om utvidet jakttid på kanadagås og stripegås, Farsund (Nr. 1832).......................... 8 Des. 19. Forskrift om åpen brenning og brenning av avfall i småovner, Rissa (Nr. 1833).................... 8 Des. 20. Forskrift om vann- og avløpsgebyrer, Modum (Nr. 1834)...................................................... 9 Des. 23. Forskrift om tillatte vekter og dimensjoner for kjøretøy på fylkes- og kommunale veger (vegliste for Nord-Trøndelag), Nord-Trøndelag (Nr. 1835) .................................................. 9 Sep. 11. Forskrift for adressetildeling, Bjerkreim (Nr. 1849) .............................................................. 9 Okt. 29. Forskrift om åpen brenning og brenning av avfall i småovner, Drammen (Nr. 1850) ........... 10 Nov. 6. Forskrift om utvidet jakttid -

3 Plikten Til Å Straks Varsle, Undersøke Og Sette Inn Tiltak Dersom En Som Jobber På Skolen Krenker En Eller Flere Elever

Saksbehandler: Rannveig Dahlen Wesnes Vår dato: Vår referanse: 24.09.2019 2019/2589 Hesnes skole Montessoriskolen i Grimstad ved styrets leder TILSYNSRAPPORT - VEDTAK Skolens aktivitetsplikt for å sikre at elevene har et trygt og godt skolemiljø Hesnes skole Montessoriskolen i Grimstad Org.nr. 985923051 Postadresse: Telefon: E-post: Postboks 9359 Grønland, +47 23 30 12 00 [email protected] 0135 OSLO Org.nr: Internett: NO 970 018 131 www.udir.no Side 2 av 31 Sammendrag Temaet for dette tilsynet er skolens aktivitetsplikt for å sikre at elevene har et trygt og godt skolemiljø. Formålet med aktivitetsplikten er å sikre at skolen handler raskt og riktig når en elev ikke har det trygt og godt på skolen. Alle som jobber på skolen har en plikt til å følge med, gripe inn og varsle hvis de får mistanke om eller kjennskap til at en elev ikke har det trygt og godt, og skolen har en plikt til å undersøke og sette inn egnede tiltak som sørger for at eleven får et trygt og godt skolemiljø. Elevene har rett til å bli hørt og til å uttale seg om sin egen situasjon. Vi besøkte skolen 14. og 15. mai 2019, og snakket med elever, foreldre, ansatte og daglig leder (rektor). I tillegg har skolen gjennomført en egenvurdering og sendt inn øvrig dokumentasjon til oss. Med utgangspunkt i den informasjonen vi har mottatt gjennom egenvurderinger, dokumentasjon og intervjuer, har vi konkludert med at skolen har en praksis for å følge med på om elevene har det trygt og godt, gripe inn overfor krenkelser og undersøke saken hvis det kommer et varsel om at en elev ikke har det trygt og godt. -

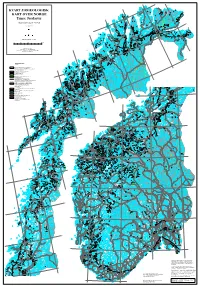

Jordarter V E U N O T N a Leirpollen

30°E 71°N 28°E Austhavet Berlevåg Bearalváhki 26°E Mehamn Nordkinnhalvøya KVARTÆRGEOLOGISK Båtsfjord Vardø D T a e n a Kjøllefjord a n f u j o v r u d o e Oksevatnet t n n KART OVER NORGE a Store L a Buevatnet k Geatnjajávri L s Varangerhalvøya á e Várnjárga f g j e o 24°E Honningsvåg r s d Tema: Jordarter v e u n o t n a Leirpollen Deanodat Vestertana Quaternary map of Norway Havøysund 70°N en rd 3. opplag 2013 fjo r D e a T g tn e n o a ra u a a v n V at t j j a n r á u V Porsanger- Vadsø Vestre Kjæsvatnet Jakobselv halvøya o n Keaisajávri Geassájávri o Store 71°N u Bordejávrrit v Måsvatn n n i e g Havvannet d n r evsbotn R a o j s f r r Kjø- o Bugøy- e fjorden g P fjorden 22°E n a Garsjøen Suolo- s r Kirkenes jávri o Mohkkejávri P Sandøy- Hammerfest Hesseng fjorden Rypefjord t Bjørnevatn e d n Målestokk (Scale) 1:1 mill. u Repparfjorden s y ø r ø S 0 25 50 100 Km Sørøya Sør-Varanger Sállan Skáiddejávri Store Porsanger Sametti Hasvik Leaktojávri Kartet inngår også i B áhèeveai- NASJONALATLAS FOR NORGE 20°E Leavdnja johka u a Lopphavet -

Fokus På Vipa I Aust-Agder I 2017

Fokus på vipa i Aust-Agder i 2017 Pressemelding: Norsk Ornitologisk forening avdeling Aust-Agder (NOF avd. Aust-Agder) Vipebestanden er i dag på et historisk lavmål både i Aust-Agder og i landet som helhet. Dårlig hekkesuksess er hovedårsaken. I den forbindelse inviterer NOF avd. Aust-Agder forvaltningen og landbruksnæringen til et samarbeid for å prøve å snu den negative trenden vårt i fylke. Lignende prosjekter pågår andre steder i landet, blant annet i Vest- Agder og Hordaland. Bakgrunnen for vårt lokale prosjekt er en kontakt foreningen hadde med en gårdbruker i Grimstad kommune i 2013. Vedkommende fortalte om problemet med vipereir på åkrene som blir kjørt ned og ødelagt av traktor og redskaper i våronna, og om sitt ønske om å finne en løsning på problemet. Forsøk på å flytte reir ut til kanten av åkeren hadde ikke ført fram siden vipene ikke ville akseptere det som sitt eget lenger. Bonden viste stor vilje til å hjelpe vipa, og vi tror at mange gårdbrukere er motivert til å gjøre en innsats for å bedre vipas hekkesuksess i fylket. Problemet har i stor grad vært mangel på kunnskap for det er ikke spesielt vanskelig. I et opplegg koordinert av foreningens styre er vi nå senvinter/tidlig vår 2017 i gang med å kontakte en del aktuell gårdbrukere for å informere om aktuelle tiltak og om ønskelig fra gårdbrukernes side, avtale et samarbeid. Et samarbeid er allerede etablert med flere bønder i fylket. Disse viser stor velvilje og et stort engasjement. Utfordringene består i at reir og egg kan ødelegges ved pløying, harving, planting, såing, gjødsling og sprøyting.