Che Guevara's Bolivia Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – Issues of National Identity and Proto-Celtic Substratum

Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 Celts and the Castro Culture in the Iberian Peninsula – issues of national identity and Proto-Celtic substratum Silvana Trombetta1 Laboratory of Provincial Roman Archeology (MAE/USP) [email protected] Received: 03/29/2018 Approved: 04/30/2018 Abstract : The object of this article is to discuss the presence of the Castro Culture and of Celtic people on the Iberian Peninsula. Currently there are two sides to this debate. On one hand, some consider the “Castro” people as one of the Celtic groups that inhabited this part of Europe, and see their peculiarity as a historically designed trait due to issues of national identity. On the other hand, there are archeologists who – despite not ignoring entirely the usage of the Castro culture for the affirmation of national identity during the nineteenth century (particularly in Portugal) – saw distinctive characteristics in the Northwest of Portugal and Spain which go beyond the use of the past for political reasons. We will examine these questions aiming to decide if there is a common Proto-Celtic substrate, and possible singularities in the Castro Culture. Keywords : Celts, Castro Culture, national identity, Proto-Celtic substrate http://ppg.revistas.uema.br/index.php/brathair 39 Brathair 18 (1), 2018 ISSN 1519-9053 There is marked controversy in the use of the term Celt and the matter of the presence of these people in Europe, especially in Spain. This controversy involves nationalism, debates on the possible existence of invading hordes (populations that would bring with them elements of the Urnfield, Hallstatt, and La Tène cultures), and the possible presence of a Proto-Celtic cultural substrate common to several areas of the Old Continent. -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Web Apr 06.Qxp

On-Line version TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 18 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 21 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 24 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 30 Special Operations Forces History Page 34 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command historic activation Gen. Doug Brown, commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, passes the MARSOC flag to Brig. Gen. Dennis Hejlik, MARSOC commander, during a ceremony at Camp Lejune, N.C., Feb. 24. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Marines run out of cover during a short firefight in Ar Ramadi, Iraq. The foot patrol was attacked by a unknown sniper. Courtesy photo by Maurizio Gambarini, Deutsche Press Agentur. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Special Forces trained Iraqi counter terrorism unit hostage rescue mission a success, page 7 SF Soldier awarded Silver Star for heroic actions in Afghan battle, page 14 20th Special Operations Squadron celebrates 30th anniversary, page 24 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

CV-Ligia María Castro Monge (EN-Julio2017-RIM)

LIGIA MARIA CASTRO-MONGE [email protected] [email protected] Telephone: (506) 8314-3313 Skype: lcastromonge San José, Costa Rica COMPETENCIES Prominent experience in the economic and financial fields, both at the academic and practical levels. In the financial field, the specialization areas are financial institutions’ regulation, risk analysis and microfinance. Excellent capacity for leadership, decision-making and teamwork promotion. Oriented towards results, innovative and with excellent interpersonal relationships. EXPERIENCE: CONSULTING May-Sept 17 The SEEP Network U.S.A. Awareness raising & dissemination of best practices for disaster risk reduction among FSPs, their clients and relevant stakeholders • To develop, pilot and finalize workshop methodology designed to raise awareness and disseminate existing best practices related to disaster risk reduction for FSPs, their clients and other relevant stakeholders working in disaster and crisis-affected environments. • Pilot projects to be conducted in Nepal (July 2017) and the Philippines (August 2017) Jan-Sept 17 BAYAN ADVISERS Jordan Establishment of a full-function risk management unit for Vitas-Jordan • Diagnostic analysis and evaluation phase applying the RMGM to define an institutional road map for strengthening the risk management framework and function including, among others, a high-level risk management department structure and the establishment of a risk committee at the board level • Based on the institutional road map to strengthen risk management, development -

Che Guevara's Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy

SOCIALIST VOICE / JUNE 2008 / 1 Contents 249. Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy. John Riddell 250. From Marx to Morales: Indigenous Socialism and the Latin Americanization of Marxism. John Riddell 251. Bolivian President Condemns Europe’s Anti-Migrant Law. Evo Morales 252. Harvest of Injustice: The Oppression of Migrant Workers on Canadian Farms. Adriana Paz 253. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part One. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 254. Revolutionary Organization Today: Part Two. Paul Le Blanc and John Riddell 255. The Harper ‘Apology’ — Saying ‘Sorry’ with a Forked Tongue. Mike Krebs ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #249, June 8, 2008 Che Guevara’s Final Verdict on the Soviet Economy By John Riddell One of the most important developments in Cuban Marxism in recent years has been increased attention to the writings of Ernesto Che Guevara on the economics and politics of the transition to socialism. A milestone in this process was the publication in 2006 by Ocean Press and Cuba’s Centro de Estudios Che Guevara of Apuntes criticos a la economía política [Critical Notes on Political Economy], a collection of Che’s writings from the years 1962 to 1965, many of them previously unpublished. The book includes a lengthy excerpt from a letter to Fidel Castro, entitled “Some Thoughts on the Transition to Socialism.” In it, in extremely condensed comments, Che presented his views on economic development in the Soviet Union.[1] In 1965, the Soviet economy stood at the end of a period of rapid growth that had brought improvements to the still very low living standards of working people. -

Revolutionaries

Relay May/June 2005 39 contexts. In his book Revolutionaries (New York: New Press, 2001), Eric Hobsbawm notes that “all revolutionaries must always believe in the necessity of taking the initia- tive, the refusal to wait upon events to make the revolu- tion for them.” This is what the practical lives of Marx, Lenin, Gramsci, Mao, Fidel tell us. As Hobsbawm elabo- rates: “That is why the test of greatness in revolutionar- ies has always been their capacity to discover the new and unexpected characteristics of revolutionary situations and to adapt their tactics to them.... the revolutionary does not create the waves on which he rides, but balances on them.... sooner or later he must stop riding on the wave and must control its direction and movement.” The life of Che Guevara, and the Latin American insurgency that needs of humanity and for this to occur the individual as part ‘Guevaraism’ became associated with during the ‘years of this social mass must find the political space to express of lead’ of the 1960s to 1970s, also tells us that is not his/her social and cultural subjectivity. For Cuban’s therefore enough to want a revolution, and to pursue it unselfishly El Che was not merely a man of armed militancy, but a thinker and passionately. who had accepted thought, which the reality of what then was The course of the 20th century revolutions and revolu- the golden age of American imperialist hegemony and gave tionary movements and the consolidation of neoliberalism his life to fight against this blunt terrorizing instrument. -

Venezuela and Cuba: the Ties That Bind

Latin American Program | January 2020 A portrait of the late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez in between the Cuban and Venezuelan flags.Credit: Chávez Fusterlandia (On the left) A silhouetted profile of Fidel Castro in his military cap says “the best friend.” Dan Lundberg, March 18, 2016 / Shutterstock Venezuela and Cuba: The Ties that Bind I. Two Nations, One Revolution: The Evolution of Contemporary Cuba-Venezuela Relations By Brian Fonseca and John Polga-Hecimovich CONTENTS “Cuba es el mar de la felicidad. Hacia allá va Venezuela.” I. Two Nations, One (“Cuba is a sea of happiness. That’s where Venezuela is going.”) Revolution: The Evolution —Hugo Chávez Frías, March 8, 2000 of Contemporary Cuba- Venezuela Relations Contemporary Cuban-Venezuelan relations blossomed in the late 1990s, due in large part By Brian Fonseca and John Polga-Hecimovich to the close mentor-pupil relationship between then-presidents Fidel Castro Ruz and Hugo Chávez Frías. Their affinity grew into an ideological and then strategic partnership. Today, these ties that bind are more relevant than ever, as Cuban security officials exercise influ- II. The Geopolitics of Cuba–Venezuela-U.S. ence in Venezuela and help maintain the Nicolás Maduro government in power. Details of the Relations: relationship, however, remain shrouded in secrecy, complicating any assessment of Cuba’s An Informal Note role in Venezuela. The Venezuelan and Cuban governments have not been transparent about By Richard E. Feinberg the size and scope of any contingent of Cuban military and security -

Restructuring the Socialist Economy

CAPITAL AND CLASS IN CUBAN DEVELOPMENT: Restructuring the Socialist Economy Brian Green B.A. Simon Fraser University, 1994 THESISSUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMEW FOR THE DEGREE OF MASER OF ARTS Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies O Brian Green 1996 All rights resewed. This work my not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Siblioth&ye nationale du Canada Azcjuis;lrons and Direction des acquisitions et Bitjibgraphic Sewices Branch des services biblicxpphiques Youi hie Vofrergfereoce Our hie Ncfre rb1Prence The author has granted an L'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive ficence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant & la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationafe du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette these a la disposition des personnes int6ress6es. The author retains ownership of L'auteur consenre la propriete du the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui protege sa Neither the thesis nor substantial th&se. Ni la thbe ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiefs de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent 6tre imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son autorisatiow. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Sion Fraser Universi the sight to Iend my thesis, prosect or ex?ended essay (the title o7 which is shown below) to users o2 the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the Zibrary of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Portuguese Family Names

Portuguese Family Names GERALD M. MOSER 1 Point Cabrillo reflects the Spanish spelling of the nickname of J oao Rodrigues Oabrilho - "the I(id," perhaps a play on words, if the Viscount De Lagoa was correct in assuming that this Portuguese navigator was born in one of the many villages in Portugal called Oabril (Joao Rodrigues Oabrilho, A Biographical Sketch, Lisbon, Agencia Geral do mtramar, 1957, p. 19). 2 Oastroville, Texas, -- there is another town of the same name in California - was named after its founder, Henry Oastro, a Portuguese Jew from France, who came to Providence, R.I., in 1827. From there he went to Texas in 1842, launching a colonization scheme, mainly on land near San Antonio. I came upon the story in the Genealogy Department of the Dallas Public Library, on the eve of reading to the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese a paper on "Cultural Linguistics: The Case of the Portuguese Family Names" (December 28, 1957). The present article is an enlarged version of that paper. 30 38 Gerald M. Moser versational style as 0 Gomes alfaiate, ("that Tailor Gomes"), same manner in which tradesmen and officials were identified in the Lis- . bon of the fifteenth century (see Appendix 2). E) A fifth type of family name exists in Portugal, which has not yet been mentioned. It includes names due to religious devotion, similar to but. not identical with the cult of the saints which has furnished so many baptismal names. These peculiar devotional names are not used as first names in Portugal, although some of them are commonly used thus in Spain. -

The Charismatic Revolutionary Leadership Trajectories of Fidel Castro and Lázaro Cárdenas: from Guerrillas to Heads of State in the Age of US Imperialism

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 15 Number 1 Article 6 11-16-2020 The Charismatic Revolutionary Leadership Trajectories of Fidel Castro and Lázaro Cárdenas: From Guerrillas to Heads of State in the Age of US Imperialism Joseph J. Garcia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Political Science Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Garcia, Joseph J. (2020) "The Charismatic Revolutionary Leadership Trajectories of Fidel Castro and Lázaro Cárdenas: From Guerrillas to Heads of State in the Age of US Imperialism," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 15 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol15/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Global Initiatives Vol. 15, No. 1, 2020, pp. 63-79. The Charismatic Revolutionary Leadership Trajectories of Fidel Castro and Lázaro Cárdenas: From Guerrillas to Heads of State in the Age of U.S. Imperialism Joseph J. García Abstract After attempting to overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista in 1953, Fidel Castro fled to Mexico where he, his brother, Raul Castro, Ernesto Che Guevara, and other revolutionaries were later jailed by the Mexican government under the orders of the Batista dictatorship to be returned to Cuba. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

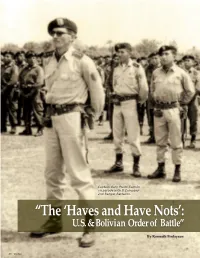

Captain Gary Prado Salmón on parade with B Company 2nd Ranger Battalion. “The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U. S. & Bolivian Order of Battle” By Kenneth Finlayson 40 Veritas they arrived in Guatemala Belize Bolivia in April 1967, U.S. SOUTHERN When Honduras the 8th Special Forces Group Mobile COMMAND Training Team (MTT) commanded El Salvador Nicaragua by Major (MAJ) Ralph W. “Pappy” Shelton was literally the “tip of the Costa Rica Guyana Venezuela spear” of the American effort to Panama Suriname support Bolivia in its fight against a French Guiana Cuban-sponsored insurgency. The 16 men Colombia represented a miniscule economy of force for the 1.4 million-man U.S. Army in 1967 that was fighting in South Vietnam and which was the Ecuador bulk of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces defending Europe against the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. In stark contrast was the Bolivian Army, a 15,000-man force of ill-trained conscripts with out-moded equipment, threatened by Brazil an insurgency. This friendly order of battle article will Peru look at the United States Army forces, in particular those units and missions supporting the U.S. strategy in Latin Bolivia America. It will then examine the Bolivian Armed Forces after the 1952 Revolution and the state of the Bolivian Army Chile when MAJ Shelton and his team arrived to train the 2nd Ranger Paraguay Battalion. It was clearly a case of the “Haves and Have-nots.” The United States Army of 1967 was a formidable force of thirteen infantry divisions, four armored divisions, one cavalry division, four separate infantry brigades, and an armored cavalry regiment.1 In the Argentina Continental United States (CONUS) were two divisions (the 82nd Airborne and the 2nd Armored Division).