Hikohiko Te Uira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF

Table of Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................... 2 What Auckland consumers have to say about electricity retail issues ........................... 3 The EAP has not fully met the requirements of the terms of reference ......................... 4 The big-5 incumbent retailers are to blame for residential price increases .................... 5 Sweet-heart deals with Tiwai Smelter are keeping prices artificially high ...................... 6 Stronger wholesale and retail competition needed to make electricity more affordable ... 8 Saves & Winbacks is making the two-tier retail market problem worse ...................... 11 Late payment penalties disadvantage vulnerable Kiwis unable to pay on time ............. 14 Prepayment arrangements exploit vulnerable consumers ......................................... 18 There are questions about compliance with the Vulnerable Consumer Guidelines and the objectives of the Guidelines .................................................................................. 19 Concluding remarks and recommendations ............................................................. 20 Appendix 1: Price increases over the last 18-years largely driven by retail (energy) .... 22 Appendix 2: Manipulation of pricing data can make it look like lines are to blame ........ 27 Appendix 3: The electricity retail and generation markets are highly “concentrated” .... 30 Appendix 4: Retail competition improvements driven by the last inquiry reforms -

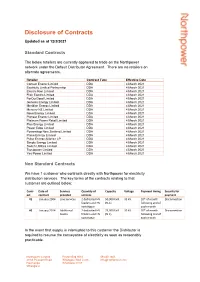

Disclosure of Contracts

Disclosure of Contracts Updated as at 12/3/2021 Standard Contracts The below retailers are currently approved to trade on the Northpower network under the Default Distributor Agreement. There are no retailers on alternate agreements. Retailer Contract Type Effective Date Contact Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Ecotricity Limited Partnership DDA 4 March 2021 Electric Kiwi Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Flick Electric Limited DDA 4 March 2021 ForOurGood Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Genesis Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Meridian Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Mercury NZ Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Nova Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Pioneer Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Platinum Power Retail Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Plus Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Power Edge Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Powershop New Zealand Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Prime Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Pulse Energy Alliance LP DDA 4 March 2021 Simply Energy Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Switch Utilities Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Trustpower Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Yes Power Limited DDA 4 March 2021 Non Standard Contracts We have 1 customer who contracts directly with Northpower for electricity distribution services. The key terms of the contracts relating to that customer are outlined below: Contr Date of Services Quantity of Capacity Voltage Payment timing Security for act contract provided services payment #1 January 2004 Line Services 2 dedicated HV 50,000 kVA 33 kV 20th of month Disconnection feeders and HV (N-1) following end of switchgear each month #2 January 2014 Additional 2 dedicated HV 25,000 kVA 33 kV 20th of month Disconnection Assets feeders and HV (N-1) following end of switchgear each month In the event that supply is interrupted to this customer the Distributor is required to resume the conveyance of electricity as soon as reasonably practicable. -

Solar Pv and Batteries in New Zealand – Consumer Centric Electricity

SOLAR PV AND BATTERIES IN NEW ZEALAND – CONSUMER CENTRIC ELECTRICITY November 2016 ITP Renewables Australia Benefits of Distributed PV in NZ- Draft Report About IT Power The IT Power Group, formed in 1981, is a specialist renewable energy, energy efficiency and carbon markets consulting company. The group has offices and projects throughout the world. IT Power (Australia) Pty Ltd (ITP) was established in 2003 and has undertaken a wide range of projects, including designing grid-connected renewable power systems, providing advice for government policy, feasibility studies for large, off-grid power systems, developing micro-finance models for community-owned power systems in developing countries and modelling large-scale power systems for industrial use. The staff at ITP have backgrounds in renewable energy and energy efficiency, research, development and implementation, managing and reviewing government incentive programs, high level policy analysis and research, including carbon markets, engineering design and project management. ITP/A0215 – November 2016 Benefits of Distributed PV in NZ – Draft Report Document Control Record Document prepared by: IT Power (Australia) Pty Limited Level 1, 19-23 Moore St, Turner, ACT, 2612, Australia PO Box 6127, O’Connor, ACT, 2602, Australia Tel. +61 2 6257 3511 Fax. +61 2 6257 3611 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.itpau.com.au Document Control Proposal title Benefits of Distributed PV in NZ Client RFP No. NA ITP Project Number A0215 Client SEANZ Client Contact Brendan Winitana Rev Date Status Author/s Project Manager Approved Rob Passey, Annie Ngo, Muriel Watt, 1 4 Nov 2016 Draft Rob Passey Muriel Watt Graham Henricksen 2 11 Nov 2016 Final Rob Passey, Annie Ngo, Muriel Watt, Muriel Watt Rob Passey Graham Henricksen A person or organisation choosing to use documents prepared by IT Power (Australia) Pty Ltd accepts the following: a) Conclusions and figures presented in draft documents are subject to change. -

Energy Complaints Scheme – Accepted Deadlocked Complaints Report for the Period 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021

Energy Complaints Scheme – accepted deadlocked complaints report for the period 1 April 2020 - 31 March 2021 Accepted deadlocked complaints The tables below show the number of deadlocked complaints that were accepted for consideration, and the relevant provider. Not all providers in the Energy Complaints Scheme had an accepted deadlocked complaint in this period. A full provider list is available on our website: www.utilitiesdisputes.co.nz The tables also show each providers’ market share, which is calculated by the number of installation control points (ICPs) or equivalent. Total ICPs (or equivalent) were calculated on 28 February 2021 from ICPs on the electricity and gas registries, and customer numbers obtained from providers. Distributors Distributor Accepted Share of Total ICPs Market share deadlocked accepted (or of ICPs (or complaints deadlocked equivalent) equivalent) complaints Alpine Energy 1 1.8% 33,113 1.3% Aurora Energy 7 12.7% 92,584 3.7% Counties Power 2 3.6% 44,978 1.8% Electra 1 1.8% 45,697 1.8% ElectroNet Services * 1 1.8% 0 0.0% Horizon Networks 1 1.8% 24,940 1.0% MainPower 1 1.8% 41,494 1.6% Northpower 3 5.5% 60,326 2.4% Orion 1 1.8% 208,259 8.2% Powerco 6 10.9% 447,295 17.7% The Lines Company (TLC) 3 5.5% 23,716 0.9% Top Energy 4 7.3% 33,049 1.3% Unison 4 7.3% 113,586 4.5% Vector 17 30.9% 699,786 27.7% WEL Networks 3 5.5% 95,851 3.8% Total 55 100% 1,964,674 77.8% Total ICPs (or equivalent) for all electricity and gas distributors: 2,524,362 Key: *Subsidiary of Westpower. -

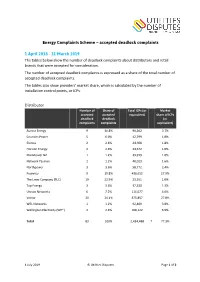

Energy Complaints Scheme – Accepted Deadlock Complaints 1

Energy Complaints Scheme – accepted deadlock complaints 1 April 2018 - 31 March 2019 The tables below show the number of deadlock complaints about distributors and retail brands that were accepted for consideration. The number of accepted deadlock complaints is expressed as a share of the total number of accepted deadlock complaints. The tables also show providers’ market share, which is calculated by the number of installation control points, or ICPs. Distributor Number of Share of Total ICPs (or Market accepted accepted equivalent) share of ICPs deadlock deadlock (or complaints complaints equivalent) Aurora Energy 9 10.8% 90,262 3.7% Counties Power 5 6.0% 42,799 1.8% Electra 2 2.4% 44,908 1.8% Horizon Energy 2 2.4% 24,672 1.0% MainPower NZ 1 1.2% 39,919 1.6% Network Tasman 1 1.2% 40,023 1.6% Northpower 3 3.6% 58,772 2.4% Powerco 9 10.8% 436,652 17.9% The Lines Company (TLC) 19 22.9% 23,551 1.0% Top Energy 3 3.6% 32,330 1.3% Unison Networks 6 7.2% 111,577 4.6% Vector 20 24.1% 675,857 27.8% WEL Networks 1 1.2% 92,400 3.8% Wellington Electricity (WE*) 2 2.4% 168,122 6.9% Total 83 100% 2,434,488 † 77.3% 4 July 2019 © Utilities Disputes Page 1 of 2 Retail brand Number of Share of Total ICPs (or Market accepted accepted equivalent) share of ICPs deadlock deadlock (or complaints complaints equivalent) Contact 11 8.3% 478,525 18.3% Ecotricity 5 3.8% 5,640 0.2% Electric Kiwi 4 3.0% 36,132 1.4% Elgas 7 5.3% 31,314 1.2% Energy Online 3 2.3% 106,576 4.1% Flick Electric Co 4 3.0% 20,702 0.8% Genesis Energy * 20 15.0% 566,276 21.6% GLOBUG 4 3.0% -

Presentation Title

2021 Annual Results Presentation 25 AUGUST 2021 Highlights construction of $395M 14% New Zealand 15% Australian sales Harapaki farm commenced sales growth growth 171 GWh1 in MoU’s or stable ordinary 7% Australasian contracted for South Island process heat dividend customer growth severe 2021 drought carbon neutral, 27% increasing gender pay total emissions equity and women in managed reduction business 1157 GWh in Memorandums of Understanding, 14 GWh contracted (annual volumes) 25 AUGUST 2021 2021 ANNUAL RESULTS PRESENTATION 2 Our people . 18 LTI injuries in FY21, an increase in injury Workforce measures numbers compared to FY20 120% FY21 FY20 . Staff engagement normalising to pre-COVID levels 97% 96% . 85% Increase to 97% gender pay equity 90% 78% 60% 48% 46% 37% 34% Lost time injury frequency rate 30% Meridian employees Meridian on-site contractors 18 15.0 15 13.6 0% 12 Women in the Women in senior Gender pay Engagement 8.9 9 7.4 7.8 business roles equity 4.5 Source: Meridian 6 4.2 3.4 3 1.7 0.0 0 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Financial year ended 30 June Source: Meridian 25 AUGUST 2021 2021 ANNUAL RESULTS PRESENTATION 3 Our strategy Champion Optimise Grow Competitive markets Trading & asset management Retail Sustainability Re-consenting Generation Strategic Strategic initiatives Climate action Financing Flux Grow a clear sustainability leadership NZ’s highest customer satisfaction position NZ’s largest and fastest growing retailer Use our 5,000 GWh renewable opportunity to 3 buildable options by 2024 year fast-track NZ’s decarbonisation -

Thinktv Electric Kiwi Presentation Deck

THE VALUE OF BRAVERY ANDREW COOPER CHIEF MARKETING OFFICER Goals for 2020 Share of Trader 25.0% 2019 Media Splits 20.0% 15.0% Search 10.0% Social Programmatic VOD 5.0% 0.0% 2016 2017 2018 2019 Contact Energy Electric Kiwi Energy Online Flick Electric Genesis Energy Mercury NZ Meridian Energy Nova Energy Powershop Pulse Energy Switch Utilities TrustPower Note: A ‘trader switch’ is a person changing power companies (as opposed to a ‘mover switch’ which is a person moving house). COVID Lockdown Levels 3 4 2 $90,000 3 $80,000 $70,000 28 Feb 7 May 27 May First COVID case in NZ EK Shoot TV booked $60,000 $50,000 $40,000 $30,000 $20,000 $10,000 $ Dec 30 Jan 6, Jan 13 Jan 20 Jan 27 Feb 3, Feb 10 Feb 17 Feb 24 Mar 2, Mar 9, Mar 16 Mar 23 Mar 30 Apr 6, Apr 13 Apr 20 Apr 27 May 4, May 11 May 18 May 25 Jun 1, Jun 8, Jun 15 Jun 22 Jun 29 Jul 6, Jul 13 Jul 20 Jul 27 Aug 3, Aug 10 Search Social Programmatic VOD Linear TV Cinema The creative Awareness Significant gains, which have been maintained Unprompted Prompted Customer response Consideration and Preference Its amazing that EK is number one for preference, and again maintained post campaign Consideration Preference COVID Lockdown Levels 3 4 3 2 $90,000 1600 $80,000 1400 $70,000 28 Feb 7 May 27 May 1200 First COVID case in NZ EK Shoot TV booked $60,000 1000 $50,000 800 $40,000 600 $30,000 400 $20,000 $10,000 200 $ 0 Dec 30 Jan 6, Jan 13 Jan 20 Jan 27 Feb 3, Feb 10 Feb 17 Feb 24 Mar 2, Mar 9, Mar 16 Mar 23 Mar 30 Apr 6, Apr 13 Apr 20 Apr 27 May 4, May 11 May 18 May 25 Jun 1, Jun 8, Jun 15 Jun 22 Jun 29 Jul 6, Jul 13 Jul 20 Jul 27 Aug 3, Aug 10 Search Social Programmatic VOD Linear TV Cinema Sales EK number one in trader in 2020 Sales for 2020 125% of our 21.0% ambitious targets. -

Additional Speakers | More Content

ADDITIONAL SPEAKERS | MORE CONTENT 4-5 MARCH 2015, SKYCITY CONVENTION CENTRE, AUCKLAND HEAR FROM THE SECtor’S LEADERS EMERGING CUSTOMER PRIORITIES | CONFRONTING NEW TECHNOLOGY | INFORMING CAPITAL INVESTMENT Michael Stiassny Mark Binns Vince Hawksworth Fraser Whineray Albert Brantley Alison Andrew DIAMOND SPONSOR GOLD SPONSORS NETWORK MANAGERS’ FORUM SPONSOR CAFE SPONSOR LUNCH SPONSORS NETWORKING DRINKS SPONSOR FOUNDATION parTNERS Register now at www.nzdownstream.co.nz Downstream 2015 strategic forum is the New Zealand premier event for everyone involved directly or indirectly in the energy sector. This must-attend two-day event will offer insights into current energy sector challenges, this time with a focus on changing consumer requirements and the impact of new technology. This age of information and technology empowers the consumer to make better decisions. The energy industry is not immune to changing consumer needs. To retain and increase market share, energy companies need to deliver value to consumers. With a great deal of new technology set to ‘revolutionise’ the customer experience, how does the sector justify the net benefit to energy users? We would like to invite you to join us at New Zealand’s premier energy sector event that brings together influencers and representatives from the downstream energy industry. The 2014 event saw over 330 delegates convene, and for 2015 a focus on consumers and the impact of the latest technology, will assist in setting the future direction for the industry. We are looking forward to seeing -

Energy Policies of IEA Countires

ENERGY POLICIES OF IEA COUNTRIES New Zealand 2017 Review Secure Sustainable Together ENERGY POLICIES OF IEA COUNTRIES New Zealand 2017 Review INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA), an autonomous agency, was established in November 1974. Its primary mandate was – and is – two-fold: to promote energy security amongst its member countries through collective response to physical disruptions in oil supply, and provide authoritative research and analysis on ways to ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its 29 member countries and beyond. The IEA carries out a comprehensive programme of energy co-operation among its member countries, each of which is obliged to hold oil stocks equivalent to 90 days of its net imports. The Agency’s aims include the following objectives: n Secure member countries’ access to reliable and ample supplies of all forms of energy; in particular, through maintaining effective emergency response capabilities in case of oil supply disruptions. n Promote sustainable energy policies that spur economic growth and environmental protection in a global context – particularly in terms of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions that contribute to climate change. n Improve transparency of international markets through collection and analysis of energy data. n Support global collaboration on energy technology to secure future energy supplies and mitigate their environmental impact, including through improved energy efficiency and development and deployment of low-carbon technologies. n Find solutions -

Stakeholder Feedback Received on Our September 2018 Delivery Pricing Consultation and Discussion Paper

Stakeholder feedback received on our September 2018 Delivery pricing consultation and discussion paper Published 23 October 2018 Introduction This document brings together all of the feedback we received on our September 2018 consultation and discussion paper. It is ordered by the name of the party, as follows: Electric Kiwi Flick Genesis Energy Meridian Energy Powershop Further responses were received from Contact Energy and Powershop and marked as confidential, and are not presented here. 9 October 2018 Orion New Zealand Limited By email: [email protected] Dear Bruce Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Orion pricing consultation paper for 2019/20. As we are a residential-based business, our comments are in relation to residential pricing only. Rather than commenting on each specific question, we provide our general views below. As you may be aware, Electric Kiwi provides a free hour of off-peak power to customers each day. This provides a sharp price signal for customers to shift consumption to off-peak periods of the day. This, in part, smooths out some of the network peaks as customers have the incentive to use non- essential electricity at off-peak times (e.g. the dishwasher, washing machine etc). As such, this has positive benefits for the distribution network as a whole. We have seen in practice that, because the customer knows they can save money at a predictable time, customers are keen to actively shift their load. Therefore, if there is a predictable price signal, customers will actively respond. We do not agree that the network-peak based pricing structure is achieving its intended purpose. -

Options Paper for Information Disclosure

CONSULTATION PAPER Options for Information Disclosure in the Wholesale Gas Sector SUBMISSIONS CLOSE: 5:00PM, WEDNESDAY, 17 APRIL 2019 Executive Summary Overview Recent events in the gas industry have brought an increased focus on information availability in the sector. The industry has seen several major production outages occurring over a relatively short space of time and this has led to questions, from both within the industry and the broader energy sector, about information transparency and asymmetry in the wholesale gas market. On 25 July 2018, Gas Industry Co received a letter from the Minister of Energy and Resources Hon Dr Megan Woods, where she raised her concern that if information is not required to be disclosed in a timely manner it may have a material effect on the wider market for gas. The Minister requested that Gas Industry Co investigate the current information disclosure requirements and consider whether they are adequate. Following the Minister’s letter, Gas Industry Co has established a new workstream on information disclosure. This workstream will consider whether current market arrangements related to information disclosure in the wholesale gas sector are sufficient or whether further arrangements are required. This paper represents the first step in the workstream. Potential Information Issues The supply side of the New Zealand gas sector is concentrated. The capital-intensive nature of gas supply combined with a desire for supply certainty from major gas users has led to long- term, bilateral gas supply agreements being the preferred market arrangement. This prevalence of bilateral supply contracts is a contributing factor in possible information transparency and asymmetry issues in the wholesale gas market. -

Heavy Ev Lands for Foodstuffs

JULY 2020 HEAVY EV LANDS FOR FOODSTUFFS P. 06 P. 10 P. 12 NEW APPROACH FOR EV WAIT BEGINS FOR OPENLOOP LAUNCHES DEALER TOYOTA EV Drive your business forward with Call Steve Owens now on 021 947 752 WWW.EVSANDBEYOND.CO.NZ | EVS AND BEYOND JULY 2020 1 HEAVY EV KEEPS THINGS COOL AND GREEN From the tailgate to the engine and the fridge-freezer unit that sits on top, everything on Foodstuffs’ new heavy EV is powered by a battery. With help from the Energy Efficiency Foodstuffs NZ sustainability manager Mike Sammons says data on the truck will and Conservation Authority (EECA), the Sammons says it’s “a huge feat of Kiwi be collected over the next 12 months new vehicle is now making deliveries ingenuity”. “to really get an understanding of the as New Zealand’s first electric powered “We couldn’t purchase a fully electric potential for electric trucks as a viable refrigerated heavy-duty truck. refrigerated truck, because it didn’t exist, alternative to the status quo”. It is the latest of several projects between so we had the idea to custom-build one,” EECA transport portfolio manager Richard Foodstuffs and EECA as they collaborate he says. Briggs says they could see the potential in the drive towards a carbon neutral New With carbon emissions from transport immediately. Zealand by 2050. at 18% in New Zealand, Sammons is “Heavy vehicles make up less than 5% The total cost of the truck hasn’t been optimistic this new innovation will have a of the national fleet, but are responsible totalled yet, however, EECA funded role to play in transport carbon reduction.