Rivers Called Avon Avon Is a Proper Name in English but an Ordinary Word Afon ‘River’ in Welsh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GO AVON 2021 Update: Bus Transportation Available!!

Michael Renkawitz, Principal Dr. Diana DeVivo, Assistant Principal David Kimball, Assistant Principal Todd Dyer, Director of School Counseling Timothy P. Filon, Coordinator of Athletics GO AVON! UPDATE August 19, 2021 Dear Class of 2025 and students new to Avon: On August 11 you received an invitation from me to participate in GO AVON!, an orientation program prior to the start of school. We are fortunate that we have a dedicated group of AHS upperclassmen who have planned this orientation session for you. I am thrilled to inform you that bus transportation is now available! Specialty Transportation will begin their morning pick-up at 8:15 a.m. using the revised bus routes listed below. Please note that these revised bus routes will be used on GO AVON! Day only and your child may be picked up/dropped off at a stop different from their regularly assigned bus location used during the school year. Students should take the bus at the nearest bus location listed below. Buses will be shared with Avon MIddle School on this day. AHS students are asked to sit in the back two sections of the bus for cohorting purposes. At dismissal, students will board the same lettered bus as they came on. Please have your child write down the letter of his/her bus, as it will be the same bus that brings your child home. Students will be dropped off along bus routes within 30 minutes of dismissal depending on the route. If you prefer to drive your child, students may be dropped off at AHS no earlier than 8:45 a.m. -

SCUDAMORE FAMILIES of WELLOW, BATH and FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440

Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, Bath & Frome, Somerset, from 1440 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKYDMORE/ SCUDAMORE FAMILIES OF WELLOW, BATH AND FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440. edited by Linda Moffatt ©2016, from the original work of Warren Skidmore. Revised July 2017. Preface I have combined work by Warren Skidmore from two sources in the production of this paper. Much of the content was originally published in book form as part of Thirty Generations of The Scudamore/Skidmore Family in England and America by Warren Skidmore, and revised and sold on CD in 2006. The material from this CD has now been transferred to the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com. Warren Skidmore produced in 2013 his Occasional Paper No. 46 Scudamore Descendants of certain Younger Sons that came out of Upton Scudamore, Wiltshire. In this paper he sets out the considerable circumstantial evidence for the origin of the Scudamores later found at Wellow, Somerset, as being Bratton Clovelly, Devon. Interested readers should consult in particular Section 5 of this, Warren’s last Occasional Paper, at the same website. The original text used by Warren Skidmore has been retained here, apart from the following. • Code numbers have been assigned to each male head of household, allowing cross-reference to other information in the databases of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study. Male heads of household in this piece have a code number prefixed WLW to denote their origin at Wellow. • In line with the policy of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study, details of individuals born within approximately the last 100 years are not placed on the Internet without express permission of descendants. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

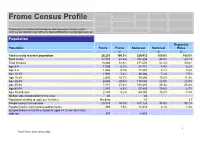

Frome Census Profile

Frome Census Profile Produced by the Partnership Intelligence Unit, Somerset County Council 2011 Census statistics from Office for National Statistics [email protected] Population England & Population Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % Total usually resident population 26,203 100.0% 529,972 100.0% 100.0% Total males 12,739 48.6% 258,396 48.8% 49.2% Total females 13,464 51.4% 271,576 51.2% 50.8% Age 0-4 1,659 6.3% 28,717 5.4% 6.2% Age 5-9 1,543 5.9% 27,487 5.2% 5.6% Age 10-15 1,936 7.4% 38,386 7.2% 7.0% Age 16-24 2,805 10.7% 54,266 10.2% 11.9% Age 25-44 6,685 25.5% 119,246 22.5% 27.4% Age 45-64 7,171 27.4% 150,210 28.3% 25.4% Age 65-74 2,247 8.6% 57,463 10.8% 8.7% Age 75 and over 2,157 8.2% 54,197 10.2% 7.8% Median age of population in the area 40 44 Population density (people per hectare) No data 1.5 3.7 People living in households 25,814 98.5% 517,124 97.6% 98.2% People living in communal establishments 389 1.5% 12,848 2.4% 1.8% Schoolchildren or full-time students aged 4+ at non term-time address 307 8,053 1 Frome Facts: 2011 census data Identity England & Ethnic Group Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % White Total 25,625 97.8% 519,255 98.0% 86.0% White: English/Welsh/Scottish/ Northern Irish/British 24,557 93.7% 501,558 94.6% 80.5% White: Irish 142 0.5% 2,257 0.4% 0.9% White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller 91 0.3% 733 0.1% 0.1% White: Other White 835 3.2% 14,707 2.8% 4.4% Black and Minority Ethnic Total 578 2.2% 10,717 2.0% 14.0% Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 57 0.2% 1,200 0.2% 0.8% Mixed: White and Black African 45 0.2% -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

HIGHLIGHTS the THREE COUNTIES KF Highlights Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5

HIGHLIGHTS THE THREE COUNTIES KF Highlights_Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5 THE BUYING SOLUTION Jonathan and Claire have purchased over £605,000,000 of property in Worcestershire, Herefordshire and the Cotswolds Whether you’re seeking the valley that catches the morning sunlight, that perfectly situated central regency townhouse, the finest picks of the social calendar or even the best shortcuts for the school run, Jonathan and Claire know the region inside out. The Buying Solution team provides property search and acquisition in London and throughout the UK. Jonathan Bramwell & Claire Owen, TBS Cotswolds specialists +44 (0)1608 503935 TheBuyingSolution.co.uk @TBSBuyingAgents KF Highlights_Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5 THE BUYING SOLUTION Welcome to Knight Frank’s Three Counties Highlights. In this year’s edition, we look at the prevailing conditions and trends that have shaped the property market in the region and also feature a selection of properties marketed by our teams during 2015. WELCOME Of course the big UK story of the year was the surprise election result in May. In property terms the uncertainty surrounding the outcome – and the possible Jonathan and Claire have introduction of the so-called Mansion Tax – had the effect of putting the brakes on a market already slowed by the increase in stamp duty introduced at the end purchased over £605,000,000 of 2014. However, by the late summer of 2015 the market was showing signs of property in Worcestershire, of absorbing these factors and getting back to business as usual. Herefordshire and the Cotswolds If there has been any lasting impact it is that sensible pricing levels have been the key to achieving successful sales. -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1 4DY J Roberts

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: Simon Butt County Hall FOI Reference: 1700165 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 3 November 2016 J Roberts ??? Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Would you be so kind as to please supply information regarding which public service bus routes within the Somerset Area are supported by funding subsidies from Somerset County Council. Our Response: I have listed the information that we hold below Registered Local Bus Services that receive some level of direct subsidy from Somerset County Council as at 1 November 2016 N8 South Somerset DRT 9 Donyatt - Crewkerne N10 Ilminster/Martock DRT C/F Bridgwater Town Services 16 Huish Episcopi - Bridgwater 19 Bridgwater - Street 25 Taunton - Dulverton 51 Stoke St. Gregory - Taunton 96 Yeovil - Chard - Taunton 162 Frome - Shepton Mallet 184 Frome - Midsomer Norton 198 Dulverton - Minehead 414/424 Frome - Midsomer Norton 668 Shipham - Street 669 Shepton Mallet - Street 3 Taunton - Bishops Hull 1 Bridgwater Town Service N6 South Petherton - Martock DRT 5 Babcary - Yeovil 8 Pilton - Yeovil 11 Yeovil Town Service 19 Bruton - Yeovil 33 Wincanton - Frome 67 Burnham - Wookey Hole 81 South Petherton - Yeovil N11 Yeovilton - Yeovil DRT 58/412 Frome to Westbury 196 Glastonbury Tor Bus Cheddar to Bristol shopper 40 Bridport - Yeovil 53 Warminster - Frome 158 Wincanton - Shaftesbury 74/212 Dorchester -

Geology of the Shepton Mallet Area (Somerset)

Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) Integrated Geological Surveys (South) Internal Report IR/03/94 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/03/00 Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) C R Bristow and D T Donovan Contributor H C Ivimey-Cook (Jurassic biostratigraphy) The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Somerset, Jurassic. Subject index Bibliographical reference BRISTOW, C R and DONOVAN, D T. 2003. Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset). British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/03/00. 52pp. © NERC 2003 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2003 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

Aggregate Blocks Brochure Central + London

Aggregate blocks Operations hours Monday to Friday 8am to 5pm Tarmac Aggregate blocks are the As a UK market leader, you can market leader in the supply of Sales enquiries Aggregate expect our blocks to meet the aggregate blocks within the UK. [email protected] most demanding of building requirements and specifications With 6 manufacturing plants, Technical support blocks nationwide we produce and supply [email protected] across different applications with over 5million m2 of aggregate blocks to Durable concrete blocks the strength of blocks available the building industry via over 55,000 Phone for all types of construction. vehicle deliveries. We employ over Andrew Thornley 0345 606 2468 120 people all with the aim to deliver a Senior Commercial Manager service to our customers based on the All Tarmac Building Products manufacturing plants “As the Senior Commercial Manager Tarmac Core Values, Proud, Ambitious operate an environmental management system for the Aggregate Blocks Business I and Collaborative. conforming to ISO:14001 and BES 6001 Responsible believe Tarmac’s Core Values – Proud, Sourcing of Construction Products, these sites are Ambitious and Collaborative, are As part of the larger Tarmac Building independently assessed for compliance by BSI. Products business, we are focused key to our successful future. Working on being the number one supplier to closely with you I hope to live and Tarmac building products offer national coverage with 6 the building industry offering a full breathe these values, continually driving blocks plants located across the UK supplying Hemelite range of products to support any improved relationships and increased and Topcrete blocks through merchants from the smallest construction requirement. -

River Avon (Bristol) – Sommerfords Fishing Association

River Avon (Bristol) – Sommerfords Fishing Association An advisory visit carried out by the Wild Trout Trust – March 2012 1 1. Introduction This report is the output of a Wild Trout Trust advisory visit undertaken on a stretch of the River Avon on waters controlled by the Sommerfords Fishing Association. The club has approximately 11Km of fishing but the advisory visit was restricted to the top beat, above Kingsmead Mill NGR ST 956844. The request for the visit was made by Mr. Ian Mock, who serves on the club committee and is the club’s Treasurer. The Sommerfords FA manages the Avon as a mixed fishery, where the emphasis is mainly on coarse fishing. The club undertakes some trout stocking on the 1km reach downstream of Kingsmead Mill, with an annual introduction of approximately 300 triploid brown trout. The top beat is not stocked and the members target both wild trout and coarse fish from this section. There is concern that results from the top beat have been in decline in recent years and the club is keen to explore opportunities to improve habitat for flow-loving, gravel spawning fish species. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Mr. Mock. Throughout the report, normal convention is followed with respect to bank identification i.e. banks are designated Left Bank (LB) or Right Bank (RB) whilst looking downstream. Sommerfords FA beat above Kingsmead Mill 2 2. Catchment overview The upper Bristol Avon rises east of the town of Chipping Sodbury in South Gloucestershire, just north of the village of Acton Turnville. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society.