Edith Wharton. Ethan Frome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCUDAMORE FAMILIES of WELLOW, BATH and FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440

Skydmore/ Scudamore Families of Wellow, Bath & Frome, Somerset, from 1440 Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study 2015 www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com [email protected] SKYDMORE/ SCUDAMORE FAMILIES OF WELLOW, BATH AND FROME, SOMERSET, from 1440. edited by Linda Moffatt ©2016, from the original work of Warren Skidmore. Revised July 2017. Preface I have combined work by Warren Skidmore from two sources in the production of this paper. Much of the content was originally published in book form as part of Thirty Generations of The Scudamore/Skidmore Family in England and America by Warren Skidmore, and revised and sold on CD in 2006. The material from this CD has now been transferred to the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com. Warren Skidmore produced in 2013 his Occasional Paper No. 46 Scudamore Descendants of certain Younger Sons that came out of Upton Scudamore, Wiltshire. In this paper he sets out the considerable circumstantial evidence for the origin of the Scudamores later found at Wellow, Somerset, as being Bratton Clovelly, Devon. Interested readers should consult in particular Section 5 of this, Warren’s last Occasional Paper, at the same website. The original text used by Warren Skidmore has been retained here, apart from the following. • Code numbers have been assigned to each male head of household, allowing cross-reference to other information in the databases of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study. Male heads of household in this piece have a code number prefixed WLW to denote their origin at Wellow. • In line with the policy of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study, details of individuals born within approximately the last 100 years are not placed on the Internet without express permission of descendants. -

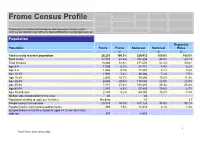

Frome Census Profile

Frome Census Profile Produced by the Partnership Intelligence Unit, Somerset County Council 2011 Census statistics from Office for National Statistics [email protected] Population England & Population Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % Total usually resident population 26,203 100.0% 529,972 100.0% 100.0% Total males 12,739 48.6% 258,396 48.8% 49.2% Total females 13,464 51.4% 271,576 51.2% 50.8% Age 0-4 1,659 6.3% 28,717 5.4% 6.2% Age 5-9 1,543 5.9% 27,487 5.2% 5.6% Age 10-15 1,936 7.4% 38,386 7.2% 7.0% Age 16-24 2,805 10.7% 54,266 10.2% 11.9% Age 25-44 6,685 25.5% 119,246 22.5% 27.4% Age 45-64 7,171 27.4% 150,210 28.3% 25.4% Age 65-74 2,247 8.6% 57,463 10.8% 8.7% Age 75 and over 2,157 8.2% 54,197 10.2% 7.8% Median age of population in the area 40 44 Population density (people per hectare) No data 1.5 3.7 People living in households 25,814 98.5% 517,124 97.6% 98.2% People living in communal establishments 389 1.5% 12,848 2.4% 1.8% Schoolchildren or full-time students aged 4+ at non term-time address 307 8,053 1 Frome Facts: 2011 census data Identity England & Ethnic Group Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % White Total 25,625 97.8% 519,255 98.0% 86.0% White: English/Welsh/Scottish/ Northern Irish/British 24,557 93.7% 501,558 94.6% 80.5% White: Irish 142 0.5% 2,257 0.4% 0.9% White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller 91 0.3% 733 0.1% 0.1% White: Other White 835 3.2% 14,707 2.8% 4.4% Black and Minority Ethnic Total 578 2.2% 10,717 2.0% 14.0% Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 57 0.2% 1,200 0.2% 0.8% Mixed: White and Black African 45 0.2% -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1 4DY J Roberts

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: Simon Butt County Hall FOI Reference: 1700165 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 3 November 2016 J Roberts ??? Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Would you be so kind as to please supply information regarding which public service bus routes within the Somerset Area are supported by funding subsidies from Somerset County Council. Our Response: I have listed the information that we hold below Registered Local Bus Services that receive some level of direct subsidy from Somerset County Council as at 1 November 2016 N8 South Somerset DRT 9 Donyatt - Crewkerne N10 Ilminster/Martock DRT C/F Bridgwater Town Services 16 Huish Episcopi - Bridgwater 19 Bridgwater - Street 25 Taunton - Dulverton 51 Stoke St. Gregory - Taunton 96 Yeovil - Chard - Taunton 162 Frome - Shepton Mallet 184 Frome - Midsomer Norton 198 Dulverton - Minehead 414/424 Frome - Midsomer Norton 668 Shipham - Street 669 Shepton Mallet - Street 3 Taunton - Bishops Hull 1 Bridgwater Town Service N6 South Petherton - Martock DRT 5 Babcary - Yeovil 8 Pilton - Yeovil 11 Yeovil Town Service 19 Bruton - Yeovil 33 Wincanton - Frome 67 Burnham - Wookey Hole 81 South Petherton - Yeovil N11 Yeovilton - Yeovil DRT 58/412 Frome to Westbury 196 Glastonbury Tor Bus Cheddar to Bristol shopper 40 Bridport - Yeovil 53 Warminster - Frome 158 Wincanton - Shaftesbury 74/212 Dorchester -

Geology of the Shepton Mallet Area (Somerset)

Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) Integrated Geological Surveys (South) Internal Report IR/03/94 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/03/00 Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) C R Bristow and D T Donovan Contributor H C Ivimey-Cook (Jurassic biostratigraphy) The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Somerset, Jurassic. Subject index Bibliographical reference BRISTOW, C R and DONOVAN, D T. 2003. Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset). British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/03/00. 52pp. © NERC 2003 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2003 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

The Reflection of Naturalism in Ethan's Life As Seen In

THE REFLECTION OF NATURALISM IN ETHAN’S LIFE AS SEEN IN EDITH WHARTON’S ETHAN FROME AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By INTEN PUSPITO Student Number: 014214139 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 ii iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest gratitude first and foremost goes to Jesus Christ. I thank Him for the blessing. I thank my mom and dad for their tender love. I dedicated this thesis for them. I thank my dearly annoying brothers and lovely sisters for always walking me through the ‘rain’ and for their unconditional love. Next, my huge gratitude goes to my Advisor and Co-Advisor, Modesta Luluk Artika W., S.S. and Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka,M.Hum. whose guidance and support have made this thesis possible to be finished. I can never thank them enough for the wisdom, knowledge and especially patience that they have shown me. To my friends I called best friends; mbak Ary, Donna and Key, Dian and Yose, Arul and Villa. I thank them for their patience for listening my grumbling. My unforgettable ‘cipika cipiki’: Anis, Irin, Puput, Vitun, Novel. I thank them for coloring my days, and showing me what friendship means. I love you all. Last but not least, my gratitude goes to Samurai R. I thank him for his unexplained support and whatever! Thank you. That means a lot. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................. i APPROVAL PAGE ....................................................................................... ii ACCEPTANCE PAGE .................................................................................. iii STATEMENT OF WORK’S ORIGINALTIY ........................................... -

Rivers Called Avon Avon Is a Proper Name in English but an Ordinary Word Afon ‘River’ in Welsh

Rivers called Avon Avon is a proper name in English but an ordinary word afon ‘river’ in Welsh. Therefore many people argue that speakers of Germanic languages (English, Scots, Norse, etc) heard a word like afon used by speakers of Celtic languages (Welsh, Gaelic, Cornish, etc) and then turned it into a proper name. This tends to get given a nationalist slant – who are the true inheritors of Iron-Age Britain? Rather silly, not just because semantic flow might have gone the other way, turning a proper name into a general word, but because it diverts attention from the really interesting part. Avon may offer a peek into the distant past, long before the Romans, perhaps even before the Bronze Age. We need to ask how and when the word avon was created. That means investigating where all rivers with names like Avon do (or did) occur and what distinctive features those rivers have in common. But first a bit of linguistics. The Indo-European root *ap- ‘water’ has descendants almost everywhere one looks. Best known are the Celtic words for ‘river’: Welsh afon, Irish ab (hence various forms such as abhann and habhana related to Scottish Gaelic abhainn and abhuinn), and Cornish or Breton forms such as aven and avon. Other words for river include Sanskrit avani, Old Prussian ape, Hittite hapa, and the ending –appe on Dutch place names. Further afield lie Persian Punjab ‘five waters’, Hindi Doab ‘two waters’, the Abana river of ancient Damascus, Sumerian abzu ‘deep water’, and ancient Greek Epirus possibly from PIE *apero- ‘shore, bank’. -

Notice of Poll

SOMERSET COUNTY COUNCIL ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR FROME EAST DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of A COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the FROME EAST DIVISION will be held on THURSDAY 4 MAY 2017, between the hours of 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM 2. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidates nomination papers are as follows: Name of Candidate Address Description Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper Eve 9 Whitestone Road The Conservative J M Harris M Bristow BERRY Frome Party Candidate B Harris P Bristow Somerset Kelvin Lum V Starr BA11 2DN Jennifer J Lum S L Pomeroy J Bristow J A Bowers Martin John Briars Green Party G Collinson Andrew J Carpenter DIMERY Innox Hill K Harley R Waller Frome J White T Waller Somerset M Wride M E Phillips BA11 2LW E Carpenter J Thomas Alvin John 1 Hillside House Liberal Democrats A Eyers C E Potter HORSFALL Keyford K M P Rhodes A Boyden Frome Deborah J Webster S Hillman BA11 1LB J P Grylls T Eames A J Shingler J Lewis David Alan 35 Alexandra Road Labour Party William Lowe Barry Cooper OAKENSEN Frome Jean Lowe R Burnett Somerset M R Cox Karen Burnett BA11 1LX K A Cooper A R Howard S Norwood J Singer 3. The situation of the Polling Stations for the above election and the Local Government electors entitled to vote are as follows: Description of Persons entitled to Vote Situation of Polling Stations Polling Station No Local Government Electors whose names appear on the Register of Electors for the said Electoral Area for the current year. -

Somerset Geology-A Good Rock Guide

SOMERSET GEOLOGY-A GOOD ROCK GUIDE Hugh Prudden The great unconformity figured by De la Beche WELCOME TO SOMERSET Welcome to green fields, wild flower meadows, farm cider, Cheddar cheese, picturesque villages, wild moorland, peat moors, a spectacular coastline, quiet country lanes…… To which we can add a wealth of geological features. The gorge and caves at Cheddar are well-known. Further east near Frome there are Silurian volcanics, Carboniferous Limestone outcrops, Variscan thrust tectonics, Permo-Triassic conglomerates, sediment-filled fissures, a classic unconformity, Jurassic clays and limestones, Cretaceous Greensand and Chalk topped with Tertiary remnants including sarsen stones-a veritable geological park! Elsewhere in Mendip are reminders of coal and lead mining both in the field and museums. Today the Mendips are a major source of aggregates. The Mesozoic formations curve in an arc through southwest and southeast Somerset creating vales and escarpments that define the landscape and clearly have influenced the patterns of soils, land use and settlement as at Porlock. The church building stones mark the outcrops. Wilder country can be found in the Quantocks, Brendon Hills and Exmoor which are underlain by rocks of Devonian age and within which lie sunken blocks (half-grabens) containing Permo-Triassic sediments. The coastline contains exposures of Devonian sediments and tectonics west of Minehead adjoining the classic exposures of Mesozoic sediments and structural features which extend eastward to the Parrett estuary. The predominance of wave energy from the west and the large tidal range of the Bristol Channel has resulted in rapid cliff erosion and longshore drift to the east where there is a full suite of accretionary landforms: sandy beaches, storm ridges, salt marsh, and sand dunes popular with summer visitors. -

New Slinky Mendip East L/Let.Indd 1 20/01/2017 14:41 Monday Pickup Area Tuesday Pickup Area Wednesday Pickup Area

What is the Slinky? How much does it cost? Slinky is an accessible bus service funded Please phone the booking office to check Mendip East Slinky by Somerset County Council for people the cost for your journey. English National unable to access conventional transport. Concessionary Travel Scheme passes can be Your local transport service used on Slinky services. You will need to show This service can be used for a variety of your pass every time you travel. Somerset reasons such as getting to local health Student County Tickets are also valid on appointments or exercise classes, visiting Slinky services. friends and relatives, going shopping or for social reasons. You can also use the Slinky Somerset County Council’s Slinky Service is as a link to other forms of public transport. operated by: Mendip Community Transport, MCT House, Who can use the Slinky? Unit 10a, Quarry Way Business Park, You will be eligible to use the Slinky bus Waterlip, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 4RN if you: [email protected] • Do not have your own transport www.mendipcommunitytransport.co.uk • Do not have access to a public bus service • Or have a disability which means you Services available: cannot access a public bus Monday to Friday excluding Public Holidays Parents with young children, teenagers, students, the elderly, the retired and people Booking number: with disabilities could all be eligible to use the Slinky bus service. 01749 880482 Booking lines are open: How does it work? Monday to Friday 9.30am to 4pm If you are eligible to use the service you will For more information on Community first need to register to become a member of Transport in your area, the scheme. -

Feltham Farm, Feltham, Frome, Somerset BA11 5NA Feltham Farm

Feltham Farm, Feltham, Frome, Somerset BA11 5NA £850,000 Freehold Feltham Farm, Feltham Frome BA11 5NA 6 5 2 4 Acres EPC N/R £850,000 Freehold Description A study overlooks the rear stable yard. Adjacent to the A charming Grade II listed farmhouse with a range of kitchen/breakfast room is a dining room that overlooks stables and manége, set in gardens, grounds and the front gardens. The farmhouse kitchen is vaulted with paddocks of just over 4 acres. Situated on the edge of exposed beams, there is a cream electric four oven Aga. the Longleat Estate with glorious walking and riding , The large kitchen is fitted with a range of cream cabinets Feltham Farm is a super family home with a us eful range and a stable style door leads to a walk-in pantry with of outbuildings and land. Ideal for anyone wanting to window. The pantry benefits from fitted cupboards and have horses or perhaps combine home and business plumbing for washing machine. The utility room with premises (all shown edged red on the plan). The cream cabinets, Belfast sink and plumbing for a second farmhouse is Grade II listed and retains plenty of period washing machine and tumble drier and cloakroom features including exposed beams, elm boards, open complete the downstairs space. There are two staircases fireplaces, wooden winder staircases and wooden sash to the first floor, with the principal staircase rising from and mullioned windows. Dating back to the 16 th the reception room to the landing area. The generous century with later additions and alterations, the master bedroom suite overlooks the rear courtyard and accommodation is arranged over three floors and has exposed beams, a walk-in wardrobe and a provides spacious, well-proportioned living space. -

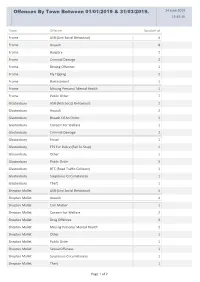

Item 15E CCTV Service Overview APPENDIX D

Offences By Town Between 01/01/2019 & 31/03/2019. 24 June 2019 15:49:36 Town Offence Number of Frome ASB (Anti Social Behaviour) 4 Frome Assault 8 Frome Burglary 2 Frome Criminal Damage 2 Frome Driving Offences 1 Frome Fly Tipping 2 Frome Harrassment 1 Frome Missing Persons/ Mental Health 1 Frome Public Order 7 Glastonbury ASB (Anti Social Behaviour) 2 Glastonbury Assault 2 Glastonbury Breach Of An Order 1 Glastonbury Concern for Welfare 1 Glastonbury Criminal Damage 2 Glastonbury Fraud 1 Glastonbury FTS For Police (Fail To Stop) 1 Glastonbury Other 1 Glastonbury Public Order 5 Glastonbury RTC (Road Traffic Collision) 1 Glastonbury Suspicious Circumstances 1 Glastonbury Theft 1 Shepton Mallet ASB (Anti Social Behaviour) 5 Shepton Mallet Assault 4 Shepton Mallet Civil Matter 1 Shepton Mallet Concern for Welfare 2 Shepton Mallet Drug Offences 4 Shepton Mallet Missing Persons/ Mental Health 2 Shepton Mallet Other 1 Shepton Mallet Public Order 1 Shepton Mallet Sexual Offenses 1 Shepton Mallet Suspicious Circumstances 1 Shepton Mallet Theft 1 Page 1 of 2 Town Offence Number of Shepton Mallet Weapons 1 Street ASB (Anti Social Behaviour) 1 Street Assault 2 Street Criminal Damage 4 Street Driving Offences 4 Street Fraud 1 Street Other 1 Street Public Order 3 Street Serious Offence (Kidnapping, Stabbing, Murder, OCG) 1 Street Suspicious Circumstances 1 Street Theft 1 Wells ASB (Anti Social Behaviour) 1 Wells Assault 5 Wells Breach Of An Order 2 Wells Burglary 1 Wells Concern for Welfare 1 Wells Criminal Damage 3 Wells Driving Offences 3 Wells Drug Offences 4 Wells DUI (Driving Under Influence) 1 Wells Missing Persons/ Mental Health 1 Wells Other 1 Wells Public Order 4 Wells Serious Offence (Kidnapping, Stabbing, Murder, OCG) 1 Wells Theft 2 57 Page 2 of 2. -

The Power of Words: the Use of Language in Ethan Frome

i The Power of Words: The Use of Language in Ethan Frome Heather Faye Spear Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in the Department of English, Liberty University December 2009 ii To my husband, Scott—thank you for your endless support and encouragement throughout the completion of this thesis, and thank you for not allowing me to take the alternative route. I would also like to dedicate this thesis to my daughter, Ava, who completed the entirety of the thesis process with me. iii Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………………ii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………....iii Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2: Zeena and Ethan ……………………………………………………………..24 Chapter 3: Ethan and Mattie …………………………………………………………….41 Chapter 4: Zeena and Mattie ……………………………………………………………..59 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….79 Endnotes…...……………………………………………………………………………..85 Bibliography.…………………………………………………………………………….87 Spear 1 The Power of Words: The Use of Language in Ethan Frome Chapter 1: Introduction Language is significant as a basis for and the advancement of civilization, influencing all facets of life: trade, religion, education, and predominantly, communication. Written and spoken words are mediums of communication rooted deeply in human nature and are intricately connected to the Divine nature of God, the institutor and originator of language. Due to man’s sinfulness, there is a complex relationship between one’s language and one’s intended meaning. Perfect communication cannot exist, but this reality and man’s finiteness do not purge language and words of their meaning; rather, it makes the relationship between the author, the text, the reader, and the world more complex.