Leverhulme International Network Continuity and Change in Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

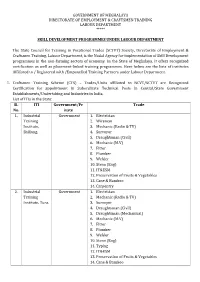

Skill Development Programmes Under Labour Department

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA DIRECTORATE OF EMPLOYMENT & CRAFTSMEN TRAINING LABOUR DEPARTMENT ***** SKILL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES UNDER LABOUR DEPARTMENT The State Council for Training in Vocational Trades (SCTVT) Society, Directorate of Employment & Craftsmen Training, Labour Department, is the Nodal Agency for implementation of Skill Development programmes in the non-farming sectors of economy in the State of Meghalaya. It offers recognized certification as well as placement-linked training programmes. Here below are the lists of institutes Affiliated to / Registered with /Empanelled Training Partners under Labour Department. 1. Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) – Trades/Units affiliated to NCVT/SCTVT are Recognized Certification for appointment in Subordinate Technical Posts in Central/State Government Establishments/Undertaking and Industries in India. List of ITIs in the State: Sl. ITI Government/Pr Trade No. ivate 1. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Wireman Institute, 3. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Shillong. 4. Surveyor 5. Draughtsman (Civil) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. IT&ESM 12. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 13. Cane & Bamboo 14. Carpentry 2. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Institute, Tura. 3. Surveyor 4. Draughtsman (Civil) 5. Draughtsman (Mechanical) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. Typing 12. IT&ESM 13. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 14. Cane & Bamboo 15. Carpentry 3. Industrial Government 1. Dress Making Training 2. Hair & Skin Institute 3. Dress Making (Advanced) (Women), Shillong 4. Govt. Government 1. Wireman Industrial 2. Plumber Training 3. Mason (Building Constructor) Institute, Sohra 4. Painter General 5. Office Assistant cum Computer Operator 5. -

Lohit District GAZETTEER of INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH LOHIT DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS

Ciazetteer of India ARUNACHAL PRADESH Lohit District GAZETTEER OF INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH LOHIT DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS LOHIT DISTRICT By S. DUTTA CHOUDHURY Editor GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1978 Published by Shri M.P. Hazarika Director of Information and Public Relations Government of Amnachal Pradesh, Shillong Printed by Shri K.K. Ray at Navana Printing Works Private Limited 47 Ganesh Chunder Avenue Calcutta 700 013 ' Government of Arunachal Pradesh FirstEdition: 19781 First Reprint Edition: 2008 ISBN- 978-81-906587-0-6 Price:.Rs. 225/- Reprinted by M/s Himalayan Publishers Legi Shopping Corqplex, BankTinali,Itanagar-791 111. FOREWORD I have much pleasure in introducing the Lohit Distri<^ Gazetteer, the first of a series of District Gazetteers proposed to be brought out by the Government of Arunachal Pradesh. A'Gazetteer is a repository of care fully collected and systematically collated information on a wide range of subjects pertaining to a particular area. These information are of con siderable importance and interest. Since independence, Arunachal Pra desh has been making steady progress in various spheres. This north-east frontier comer of the country has, during these years, witnessed tremen dous changes in social, economic, political and cultural spheres. These changes are reflected in die Gazetteers. 1 hope that as a reflex of these changes, the Lohit District Gazetteer would prove to be quite useful not only to the administrators but also to researdi schplars and all those who are keen to know in detail about one of the districts of Arunachal Pradesh. Raj Niwas K. A. A. Raja Itanagar-791 111 Lieutenant Governor, Arunachal Pradesh October 5, i m Vili I should like to take this opportunity of expressing my deep sense of gratitude to Shri K; A. -

A Comparative Study of Angami and Chakhesang Women

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF UNEMPLOYMENT PROBLEM : A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ANGAMI AND CHAKHESANG WOMEN THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIOLOGY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES NAGALAND UNIVERSITY BY MEDONUO PIENYÜ Ph. D. REGISTRATION NO. 357/ 2008 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. KSHETRI RAJENDRA SINGH DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NAGALAND UNIVERSITY H.Qs. LUMAMI, NAGALAND, INDIA NOVEMBER 2013 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my Mother Mrs. Mhasivonuo Pienyü who never gave up on me and supported me through the most difficult times of my life. NAGALAND UNIVERSITY (A Central University Estd. By the Act of Parliament No 35 of 1989) Headquaters- Lumami P.O. Mokokchung- 798601 Department of Sociology Ref. No……………. Date………………. CERTIFICATE This is certified that I have supervised and gone through the entire pages of the Ph.D. thesis entitled “A Sociological Study of Unemployment Problem: A Comparative Study of Angami and Chakhesang Women” submitted by Medonuo Pienyü. This is further certified that this research work of Medonuo Pienyü, carried out under my supervision is her original work and has not been submitted for any degree to any other university or institute. Supervisor Place: (Prof. Kshetri Rajendra Singh) Date: Department of Sociology, Nagaland University Hqs: Lumami DECLARATION The Nagaland University November, 2013. I, Miss. Medonuo Pienyü, hereby declare that the contents of this thesis is the record of my work done and the subject matter of this thesis did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that thesis has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Tripura Human Development Report II

Tripura Human Development Report II Pratichi Institute Pratichi (India) Trust 2018 2 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY Contributory Authors Sabir Ahamed Ratan Ghosh Toa Bagchi Amitava Gupta Indraneel Bhowmik Manabi Majumdar Anirban Chattapadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Joyanta Choudhury Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Arijita Dutta Pia Sen Dilip Ghosh Editors Manabi Majumdar, Sangram Mukherjee, Kumar Rana and Manabesh Sarkar Field Research Sabir Ahamed Mukhlesur Rahaman Gain Toa Bagchi Dilip Ghosh Susmita Bandyopadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Runa Basu Swagata Nandi Subhra Bhattacharjee Piyali Pal Subhra Das Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Tanmoy Dutta Pia Sen Arijita Dutta Photo Courtesy Pratichi Research Team Logistical Support Dinesh Bhat Saumik Mukherjee Piuli Chakraborty Sumanta Paul TRIPURA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT II 3 4 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY FOREWORD Amartya Sen India is a country of enormous diversity, and there is a great deal for us to learn from the varying experiences and achievements of the different regions. Tripura’s accomplishments in advancing human development have many distinguishing features which separate it out from much of the rest of India. An understanding of the special successes of Tripura is important for the people of Tripura, but – going beyond that – there are lessons here for the rest of India in appreciating what this small state has been able to achieve, particularly given the adverse circumstances that had to be overcome. Among the adversities that had to be addressed, perhaps the most important is the gigantic influx of refugees into this tiny state at the time of the partition of India in 1947 and again during the turmoil in East Pakistan preceding the formation of Bangladesh in 1971. -

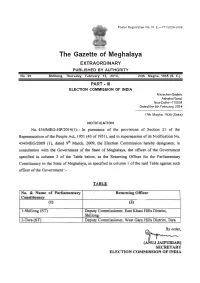

Part-III Extra 2014.Pmd

Postal Registration No. N. E.—771/2006-2008 The Gazette of Meghalaya EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 39 Shillong, Thursday, February 13, 2014, 24th Magha, 1935 (S. E.) PART - III ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi—110001 Dated the 6th February, 2014 ---------------------------------------------- 17th Magha, 1935 (Saka) NOTIFICATION 128 THE GAZETTE OF MEGHALAYA, (EXTRAORDINARY) FEBRUARY 13, 2014 [PART-III PART - III ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi—110001 Dated the 6th February, 2014 ---------------------------------------------- 17th Magha, 1935 (Saka) NOTIFICATION PART-III] THE GAZETTE OF MEGHALAYA, (EXTRAORDINARY) FEBRUARY 13, 2014 129 SHILLONG: Printed and Published by the Director, Printing and Stationery, Meghalaya, Shillong. (Extraordinary Gazette of Meghalaya) No. 77 - 700+100—18-2-2014. website:- http://megpns.gov.in/gazette/gazette.asp Postal Registration No. N. E.—771/2006-2008 The Gazette of Meghalaya EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 42 Shillong, Thursday, February 13, 2014, 24th Magha, 1935 (S. E.) PART-IV GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA DISTRICT COUNCIL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR ——— NOTIFICATIONS The 13th February, 2014. No.DCA.17/2014/34.—In pursuance of Rule 137 (1) of the Assam and Meghalaya Autonomous Districts (Constitution of District Councils) Rules 1951, as amended the following names of Contesting Candidates for the General Elections, 2014 to the Constituencies from 1 to 29 of the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council together with the party affiliattion and the Symbol allotted to each candidate are published for general information. [FORM 7A] List of Contesting Candidates [See Rule 137 (1)] Election to the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council 2014 from 1-Jirang Constituency Sl. -

District Wise EC Issued

District wise Environmental Clearances Issued for various Development Projects Agra Sl No. Name of Applicant Project Title Category Date 1 Rancy Construction (P) Ltd.S-19. Ist Floor, Complex "The Banzara Mall" at Plot No. 21/263, at Jeoni Mandi, Agra. Building Construction/Area 24-09-2008 Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110017 Development 2 G.M. (Project) M/s SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD., SINCERE DEVELOPERS (P) LTD (Hotel Project) Shilp Gram, Tajganj Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 18-12-2008 Block - 53/4, UPee Tower IIIrd Floor, Sanjav Place, Development AGRA 3 Mr. S.N. Raja, Project Coordinator, M/s GANGETIC Large Scale Shopping, Entertainment and Hotel Unit at G-1, Taj Nagari Phase-II, Basai, Building Construction/Area 19-03-2009 Developers Pvt. Ltd. C-11, Panchsheel Enclve, IIIrd Agra Development Floor, New Delhi 4 M/s Ansal Properties and Infrastructure Ltd 115, E.C. For Integrated Township, Agra Building Construction/Area 07-10-2009 Ansal Bhawan, 16, K.G. Marg, New Delhi-110001 Development 5 Chief Engineer, U.P.P.W.D., Agra Zone, Agra. “Strengthening and widening road to 6 Lane from kheria Airport via Idgah Crosing, Taj Infrastructure 11-09-2008 Mahal in Agra City.” 6 Mr. R.K. Gaud, Technical Advisor, Construction & Solid Waste Management Scheme in Agra City. Infrastructure 02-09-2008 Design Services, U.P. Jal Nigam, 2 Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg, Lucknow-226001 7 Agra Development Authority, Authority Office ADA Height, Agra Phase II Fatehbad Road, AGRA Building Construction/Area 29-12-2008 Jaipur House AGRA. Development 8 M/s Nikhil Indus Infrastructure Ltd., Mr. -

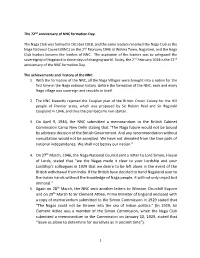

3. on April 9, 1946, the NNC Submitted a Memorandum to The

The 72nd anniversary of NNC formation Day. The Naga Club was formed in October 1918, and the same leaders renamed the Naga Club as the Naga National Council (NNC) on the 2nd February 1946 at Wokha Town, Nagaland, and the Naga Club leaders became the leaders of NNC. The aspiration of the leaders was to safeguard the sovereignty of Nagaland in those days of changing world. Today, the 2nd February 2018 is the 72nd anniversary of the NNC formation Day. The achievements and history of the NNC. 1. With the formation of the NNC, all the Naga Villages were brought into a nation for the first time in the Naga national history. Before the formation of the NNC, each and every Naga village was sovereign and republic in itself. 2. The NNC blatantly rejected the Couplan plan of the British Crown Colony for the Hill people of Frontier areas, which was proposed by Sir Robert Reid and Sir Reginald Coupland in 1946, and thus the plan became non-starter. 3. On April 9, 1946, the NNC submitted a memorandum to the British Cabinet Commission Camp New Delhi stating that “The Naga future would not be bound by arbitrary decision of the British Government. And any recommendation without consultation would not be accepted. We have not deviated from the true path of national independence. We shall not betray our nation.” 4. On 27th March, 1946, the Naga National Council sent a letter to Lord Simon, House of Lords, stated that “we the Nagas made it clear to your Lordship and your Lordship’s colleagues in 1929 that we desire to be left alone in the event of the British withdrawal from India. -

The Status of Tribal Women in Northeast India: Responding to India's Social Challenges

ISSN: 2455-3220 International Journal for Social Studies Volume 03 Issue 11 Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals October 2017 The Status of Tribal Women in Northeast India: Responding to India's Social Challenges. -Dr. ASHA SOUGAIJAM Department of Sociology Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Regional Campus, Chingmeirong, Adhimjati Complex, Imphal-795001, Manipur. INTRODUCTION Northeast India, considered as one of most interest in developing the living standards and culturally diverse regions of the world, is a tourism among these tribal occupied states. land inhabited by more than 200 fascinating tribes. It is no wonder the region has ever- Different ethnic groups and tribal groups since captured the imaginations of inhabit the region of northeast India. They all anthropologists from all over the world. have their own culture and tribal tradition and all speak their own tribal languages. This has The north eastern part of India shares its made Northeast India one of the most boundary with China, Nepal, Bhutan, culturally diverse regions of the world. The Myanmar and Bangladesh. Northeast India cuisines and attires also vary among the tribes. comprises of eight states. They are Mizoram, Each tribal community has their unique way of Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Assam, Manipur, living. Tribal people mostly live and earn Nagaland, Meghalaya and Tripura. Nagaland through the hills and forest areas. and Manipur share their boundary with Myanmar. Meghalaya and Tripura share it ORIGIN OF THE TRIBES with Bangladesh whereas Assam shares it‟s North East Indian tribes have originated with Bhutan. Sikkim shares its boundary with from the ethnic groups of Tibeto-Burmese, China, Nepal, and Bhutan. -

A Study on Socio-Cultural Function of the Deori Community

GLOBUS Journal of Progressive Education A Refereed Research Journal Vol 4 / No 1 / Jan-Jun 2014 ISSN: 2231-1335 A STUDY ON SOCIO-CULTURAL FUNCTION OF THE DEORI COMMUNITY Palash Dutta* Introduction Social customs and traditions play a vital role in the needs of the market will be the focal point of any cultural life of an ethnic group. There are customs development effort. On the social aspect of and traditions with core values which a tradition development, the main focus would be to create an bound society can afford to do away with even under enabling environment for realization of total human the most adverse situations. But the customs and potential with equal opportunities for all. Because of traditions with superficial or periphery values are their interrelation, the development efforts need to be always subjects to change since they can hardly stand grouped under the following major groups. the rapid changes specially brought about by modern A. Agricultural and allied sector. scientific advancement. Insight knowledge of the B. Social Welfare sector. social customs and traditions having core values of C. Infrastructure sector. an ethnic group is a must for administrators as well as D. Industry and commerce sector. developmental personnel working in the tribal areas. E. Essential services sector. Such knowledge is very much helpful to researchers and others with an inquisitive mind. Development of Deori Autonomous Council came into being as a Deoris economically and socially, lies in the growth result of an agreement signed among the Deoris and of the economy in the Agriculture and allied sectors. -

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India’s Northeast? Ajai Sahni? India’s Northeast is the location of the earliest and longest lasting insurgency in the country, in Nagaland, where separatist violence commenced in 1952, as well as of a multiplicity of more recent conflicts that have proliferated, especially since the late 1970s. Every State in the region is currently affected by insurgent and terrorist violence,1 and four of these – Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Tripura – witness scales of conflict that can be categorised as low intensity wars, defined as conflicts in which fatalities are over 100 but less than 1000 per annum. While there ? This Survey is based on research carried out under the Institute’s project on “Planning for Development and Security in India’s Northeast”, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It draws on a variety of sources, including Institute for Conflict Management – South Asia Terrorism Portal data and analysis, and specific State Reports from Wasbir Hussain (Assam); Pradeep Phanjoubam (Manipur) and Sekhar Datta (Tripura). ? Dr. Ajai Sahni is Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) and Executive Editor, Faultlines: Writings on Conflict and Resolution. 1 Within the context of conflicts in the Northeast, it is not useful to narrowly define ‘insurgency’ or ‘terrorism’, as anti-state groups in the region mix in a wide range of patterns of violence that target both the state’s agencies as well as civilians. Such violence, moreover, meshes indistinguishably with a wide range of purely criminal actions, including drug-running and abduction on an organised scale. Both the terms – terrorism and insurgency – are, consequently, used in this paper, as neither is sufficient or accurate on its own. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths.