Conservative Care Options for Work-Related Mechanical Shoulder Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imaging Shoulder Impingement

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Imaging shoulder impingement. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0kg9j32r Journal Skeletal radiology, 22(8) ISSN 0364-2348 Authors Gold, RH Seeger, LL Yao, L Publication Date 1993-11-01 DOI 10.1007/bf00197135 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Skeletal Radiol (1993) 22:555-561 Skeletal Radiology Review Imaging shoulder impingement Richard H. Gold, M.D., Leannc L. Seeger, M.D., Lawrence Yao, M.D. Department of Radiological Sciences, UCLA School of Medicine, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1721, USA Abstract. Appropriate imaging and clinical examinations more components of the coracoacromial arch superiorly. may lead to early diagnosis and treatment of the shoulder The coracoacromial arch is composed of five basic struc- impingement syndrome, thus preventing progression to a tures: the distal clavicle, acromioclavicular joint, anteri- complete tear of the rotator cuff. In this article, we discuss or third of the acromion, coracoacromial ligament, and the anatomic and pathophysiologic bases of the syn- anterior third of the coracoid process (Fig. 1). Repetitive drome, and the rationale for certain imaging tests to eval- trauma leads to progressive edema and hemorrhage of uate it. Special radiographic projections to show the the rotator cuff and hypertrophy of the synovium and supraspinatus outlet and inferior surface of the anterior subsynovial fat of the subacromial bursa. In a vicious third of the acromion, combined with magnetic reso- cycle, the resultant loss of space predisposes the soft nance images, usually provide the most useful informa- tissues to further injury, with increased pain and disabili- tion regarding the causes of impingement. -

Imaging in Gout and Other Crystal-Related Arthropathies 625

ImaginginGoutand Other Crystal-Related Arthropathies a, b Patrick Omoumi, MD, MSc, PhD *, Pascal Zufferey, MD , c b Jacques Malghem, MD , Alexander So, FRCP, PhD KEYWORDS Gout Crystal arthropathy Calcification Imaging Radiography Ultrasound Dual-energy CT MRI KEY POINTS Crystal deposits in and around the joints are common and most often encountered as inci- dental imaging findings in asymptomatic patients. In the chronic setting, imaging features of crystal arthropathies are usually characteristic and allow the differentiation of the type of crystal arthropathy, whereas in the acute phase and in early stages, imaging signs are often nonspecific, and the final diagnosis still relies on the analysis of synovial fluid. Radiography remains the primary imaging tool in the workup of these conditions; ultra- sound has been playing an increasing role for superficially located crystal-induced ar- thropathies, and computerized tomography (CT) is a nice complement to radiography for deeper sites. When performed in the acute stage, MRI may show severe inflammatory changes that could be misleading; correlation to radiographs or CT should help to distinguish crystal arthropathies from infectious or tumoral conditions. Dual-energy CT is a promising tool for the characterization of crystal arthropathies, partic- ularly gout as it permits a quantitative assessment of deposits, and may help in the follow-up of patients. INTRODUCTION The deposition of microcrystals within and around the joint is a common phenomenon. Intra-articular microcrystals -

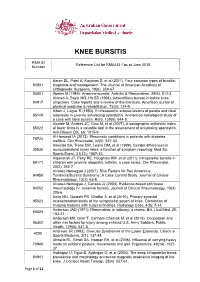

Reference List for RMA431-1As at June 2018 Number

KNEE BURSITIS RMA ID Reference List for RMA431-1as at June 2018 Number Aaron DL, Patel A, Kayiaros S, et al (2011). Four common types of bursitis: 84931 diagnosis and management. The Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 19(6): 359-67. 85001 Abeles M (1986). Anserine bursitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 29(6): 812-3. Ahmed A, Bayol MG, Ha SB (1994). Adventitious bursae in below knee 84917 amputees. Case reports and a review of the literature. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 73(2): 124-9. Albert J, Lagier R (1983). Enthesopathic erosive lesions of patella and tibial 85148 tuberosity in juvenile ankylosing spondylitis. Anatomico-radiological study of a case with tibial bursitis. Rofo, 139(5): 544-8. Alcalde M, Acebes JC, Cruz M, et al (2007). A sonographic enthesitic index 85022 of lower limbs is a valuable tool in the assessment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis, 66: 1015-9. Al-Homood IA (2013). Rheumatic conditions in patients with diabetes 78722 mellitus. Clin Rheumatol, 32(5): 527-33. Almeida SA, Trone DW, Leone DM, et al (1999). Gender differences in 39530 musculoskeletal injury rates: a function of symptom reporting. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31(12): 1807-12. Alqanatish JT, Petty RE, Houghton KM, et al (2011). Infrapatellar bursitis in 85171 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case series. Clin Rheumatol, 30(2): 263-7. Alvarez-Nemegyei J (2007). Risk Factors for Pes Anserinus 84950 Tendinitis/Bursitis Syndrome: A Case Control Study. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 13(2): 63-5. Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Canoso JJ (2004). Evidence-based soft tissue 84552 rheumatology IV: anserine bursitis. -

Pyrophosphate Arthropathy Andtheir Relation to Nodal Osteoarthrosis

Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.43.2.255 on 1 April 1984. Downloaded from Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 1984; 43, 255-257 Prevalence of periarticular calcifications in pyrophosphate arthropathy and their relation to nodal osteoarthrosis JEAN C. GERSTER, GEORGES RAPPOPORT, AND JEAN M. GINALSKI From the Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Centre and the Department ofRadiology, University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland SUMMARY X-rays of the shoulder, hand, and knee joints from 30 patients with pyrophosphate arthropathy (PA) and 30 age and sex matched control subjects were examined for periarticular, dense, homogeneous calcifications considered to be apatite deposits. They were found in 30% of the patients with PA compared with 3 3% ofthe controls. In addition in the PA group the incidence of Heberden's nodes was significantly increased in cases with periarticular calcifications, implying that mixed (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate + apatite) crystal deposition disease could be related to nodal osteoarthrosis. Apatite crystal deposits are the commonest cause of degenerative joint disease such as Heberden's and/or copyright. dense calcifications affecting the periarticular areas Bouchard's nodes was recorded in each patient. (tendons, bursae, ligaments).' Apatite crystals may Controls. This group included 30 patients taken be found intra-articularly giving rise to chronic or randomly from various categories of medical dis- acute inflammation.2 I Recently both apatite and cal- orders; they were matched for sex and age. None had cium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystals have radiological signs of PA on the x-rays of the hand and been shown to coexist in the synovial fluids of knee joints. -

Review of Adult Foot Radiology

4 Review of Adult Foot Radiology LAWRENCE OSHER In the workup of a hallux valgus deformity the practi- Metabolic disease (dystrophies included) tioner is often faced with unexpected radiographic Infections and inflammatory processes findings. Usually, the first course of action is to order Tumor and tumor-like conditions additional pedal studies, which may provide the addi- Degenerative disease and ischemic necrosis tional detail needed to help resolve or localize the apparent pathology. If the problem is within the pur- However, this approach is presumptive; not only is view of conventional radiography, a library text, if an understanding of these basic bone radiographic available, is often hurriedly consulted. changes clearly required, but one is expected to iden- It is clearly not possible to encompass all of pedal tify and then classify any lesion(s). Many radiographic radiology within the confines of a single chapter of bony abnormalities simply cannot be categorized at this volume. Designed for the physician already famil- first glance by the average physician, despite the ability iar with basic musculoskeletal radiographic terminol- to correctly describe the basic pathologic changes. For ogy, the following information will serve as a handy these practitioners, a more intuitive approach utilizing outline of foot pathology that may be encountered in clinical and laboratory data is required (studies clearly the routine workup of the patient with hallux valgus show improved accuracy in the reading of radiographs deformity. Particular effort has been given to simplify when appropriate clinical and laboratory data are pro- the process of generating basic differential diagnoses. vided). The following steps are recommended: Pictorial examples are provided throughout this chapter. -

The Integration of Acetic Acid Iontophoresis, Orthotic Therapy and Physical Rehabilitation for Chronic Plantar Fasciitis: a Case Study

0008-3194/2007/166–174/$2.00/©JCCA 2007 The integration of acetic acid iontophoresis, orthotic therapy and physical rehabilitation for chronic plantar fasciitis: a case study Ivano A Costa, BSc (Hons), BEd, DC, FCCRS(c)* Anita Dyson, BSc (Hons), DC, FCCRS(c)** A 15-year-old female soccer player presented with Cas d’une joueuse de soccer de 15 ans présentant une chronic plantar fasciitis. She was treated with acetic acid fasciite plantaire chronique. Elle a été traitée avec une iontophoresis and a combination of rehabilitation iontophorèse d’acide acétique et une combinaison de protocols, ultrasound, athletic taping, custom orthotics protocoles rééducatifs, d’ultrasons, de bandages, and soft tissue therapies with symptom resolution and d’orthèse adaptée et de traitements des tissus mous avec return to full activities within a period of 6 weeks. She résolution des symptômes et retour aux activités dans une reported no significant return of symptoms post follow-up période de six semaines. Elle n’a signalé aucun retour at 2 months. Acetic acid iontophoresis has shown significatif des symptômes après un suivi de deux mois. promising results and further studies should be L’iontophorèse d’acide acétique a présenté des résultats considered to determine clinical effectiveness. The prometteurs et des études supplémentaires doivent être combination of acetic acid iontophoresis with envisagées en vue de déterminer l’efficacité clinique. La conservative treatments may promote recovery within a combinaison d’iontophorèse d’acide acétique avec des shorter duration compared to the use of one-method traitements conservateurs est susceptible d’entraîner un treatment approaches. rétablissement plus rapide comparé aux approches (JCCA 2007; 51(3):166–174) thérapeutiques à méthode unique. -

Effective Period of Conservative Treatment in Patients with Acute

Kim et al. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2018) 13:287 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0997-5 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Effective period of conservative treatment in patients with acute calcific periarthritis of the hand Jihyeung Kim1, Kee Jeong Bae2* , Do Weon Lee1, Yo-Han Lee1, Hyun Sik Gong3 and Goo Hyun Baek1 Abstract Background: Acute calcific periarthritis of the hand is a relatively uncommon painful condition involving juxta- articular deposits of amorphous calcium hydroxyapatite. Although conservative treatments have been generally considered effective, there is little evidence regarding how long they could remain effective. Methods: We retrospectively reviewed ten patients who were diagnosed with acute calcific periarthritis of the hand from January 2015 to June 2018. We recommended the use of warm baths, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and limited activity as initial treatments. If the pain persisted despite at least 3 months of conservative treatment, we explained surgical treatment options. If the pain improved, we recommended gradual range-of-motion exercises with the continuation of daily NSAIDs use. The visual analogue scale (VAS) score for pain at each subsequent visit (3, 6, and 9 months) was compared with that of the previous visit to investigate whether the pain had decreased during each time interval. Simple radiographs taken at each visit were compared with those taken at the previous visit to determine whether any significant changes in the amount of calcification had occurred during each time interval. Results: All 10 patients with 17 affected joints continued conservative treatments for an average of 11.1 months. The average VAS score for pain at the initial visit was 7, while that at 3, 6, and 9 months was 4.3, 3.3, and 2.9, respectively. -

Shoulder Symposium 2017

Imaging of Shoulder Disorders Dr Quentin Reeves FRANZCR Auckland City Hospital / SRG Radiology Auckland Introduction • What are we trying to achieve? • Accurate diagnosis and reassurance • Effective therapy • Physiotherapy • Judicious injection therapy • Selective surgery Role of Imaging • Assist optimal patient outcomes • Define type and extent of pathology • Must know normal from abnormal • Surgical/Management planning • Arthroscopic surgery • ACC GUIDELINES FOR SHOULDER IMAGING Shoulder Disorders • Rotator cuff disease • Instability • Adhesive capsulitis • Trauma • Arthritis • Infection • Avascular necrosis • Pagets disease/Metabolic bone disease • Neoplasm Normal Anatomy • Rotator cuff tendons • Coracoacromial arch • AC Joint • Subacromial/ Subdeltoid Bursa • Biceps Tendon Normal Anatomy Etiology of Rotator Cuff Disease • Controversial • Impingement • Ischemia/degeneration • Overuse • Occupational • Athletic • Trauma • Chronic inflammatory change Important Concept • < 5% of tears occur in normal tendons Mostly middle age or older Rotator Cuff Disease • Tendinopathy • Partial thickness tears • Bursal surface • Articular surface • Intrasubstance • Full thickness tears • Small < 1cm • Moderate 1-3 cm • Large 3-5 cm • Massive > 5cm • Rotator interval tears Pattern of Rotator Cuff Tears • Most originate in anterior supraspinatus and extend anteriorly and/or posteriorly • Isolated biceps /subscapularis/infraspinatus tendon pathology is uncommon • Dislocation in older patients has higher association with tears Plain Xrays • Essential • Supraspinatus -

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rotator Cuff Syndrome in the Workplace

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rotator Cuff Syndrome in the Workplace Never Stand Still Medicine Rural Clinical School The University of New South Wales, Medicine, Rural Clinical School, Port Macquarie Campus 2013 The work was initiated and funded by Essential Energy, Australia Copyright: © The University of New South Wales, Medicine, Rural Clinical School. 2013 ISBN Number: 978–0–7334–3195–5 Suggested Citation: Hopman K, Krahe L, Lukersmith S, McColl AR, & Vine K. 2013. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rotator Cuff Syndrome in the Workplace. The University of New South Wales. This document is available online at http://rcs.med.unsw.edu.au/rotatorcuffsyndromeguidelines Report prepared by: Lukersmith & Associates Pty Ltd Editor: Dr Lee Krahe, Louise Scahill - WordFix, Kris Vine Design: Melinda Jenner and Eva Wong, Print Post Plus (P3) Design Studio Printing: Print Post Plus (P3) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rotator Cuff Syndrome in the Workplace The University of New South Wales, Medicine, Rural Clinical School, Port Macquarie Campus 2013 Research Team: Kate Hopman2, Lee Krahe1, Sue Lukersmith2, Alexander McColl1, Kris Vine1. 1 The University of New South Wales, Medicine, Rural Clinical School, Port Macquarie Campus 2 Lukersmith & Associates Pty Ltd Working Party Members Name Role Organisation Occupational & Environmental Dr David Allen Private Practice Physician Dr Roslyn Avery Rehabilitation Physician Private Practice Mr Greg Black Consumer Representative Self-Employed – Trade -

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Injections 3 Suehun G

INJE cti ON Ryan O’Connor, DO Suehun G. Ho, MD J. Steven Schultz, MD Andrew J. Haig, MD Anthony E. Chiodo, MD ����� 2007 AANEM Course G AANEM 54thAnnual Meeting Phoenix, Arizona American of Association Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine Injection Ryan C. O’Connor, DO Suehun G. Ho, MD J. Steven Schultz, MD Andrew J. Haig, MD Anthony E. Chiodo, MD 2007 COURSE G AANEM 54th Annual Meeting Phoenix, Arizona Copyright © October 2007 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 PRINTED BY JOHNSON PRINTING COM P ANY , IN C . ii Injection Faculty Ryan C. O’Connor, DO J. Steven Schultz, MD Clinical Assistant Professor Associate Professor Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Michigan State University University of Michigan East Lansing, Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan Dr. O’Connor completed premedical training at The American University Dr. Schultz received his medical degree from the University of Michigan in in Washington, DC and is a graduate of Nova-Southeastern University Ann Arbor, where he also completed a residency in physical medicine and College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Lauderdale-Davie, Florida. He rehabilitation. He is an Associate Professor in the Department of Physical completed a 1-year medical internship at Palmetto General Hospital in Medicine and Rehabilitation (PMR) at the Univerisity of Michigan Health Miami, Florida and did his residency training in physical medicine and System and Service Chief of the University of Michigan Spine Program. rehabilitation at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore He also served as Program Director of the PMR Pain Fellowship. -

Ultrasound-Diagnosed Disorders in Shoulder Patients in Daily General

Ottenheijm et al. BMC Family Practice 2014, 15:115 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/15/115 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Ultrasound-diagnosed disorders in shoulder patients in daily general practice: a retrospective observational study Ramon PG Ottenheijm1*, Inge GM van’t Klooster1, Laurens MM Starmans1, Kurt Vanderdood2, Rob A de Bie3, Geert-Jan Dinant1 and Jochen WL Cals1 Abstract Background: Ultrasound imaging (US) is considered an accurate and widely available method to diagnose subacromial disorders. Yet, the frequency of the specific US-diagnosed shoulder disorders of patients with shoulder pain referred from general practice is unknown. We set out to determine the frequency of specific US-diagnosed shoulder disorders in daily practice in these patients and to investigate if the disorders detected differ between specific subgroups based on age and duration of pain. Methods: A predefined selection of 240 ultrasound reports of patients with shoulder pain (20 reports for each month in 2011) from a general hospital (Orbis Medical Centre Sittard-Geleen, The Netherlands) were descriptively analysed. Inclusion criteria were: (i) referral from general practice, (ii) age ≥18 years, and (iii) unilateral shoulder examination. Subgroups were created for age (<65 years and ≥65 years) and duration of pain (acute or subacute (<12 weeks) and chronic (≥12 weeks)). The occurrence of each specific disorder is expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Results: With 29%, calcific tendonitis was the most frequently diagnosed disorder, followed by subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis (12%), tendinopathy (11%), partial-thickness tears (11%), full-thickness tears (8%) and AC-osteoarthritis (0.4%). For 40% of patients, no disorders were found on US. -

Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorders

Therapeutic Programs for Therapeutic Programs Musculoskeletal Disorders James F. Wyss, MD, PT Amrish D. Patel, MD, PT Literature-Driven Treatment Approach to Musculoskeletal Diagnosis for Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorders is a guide for Musculoskeletal Disorders musculoskeletal medicine trainees and physicians to the art and science of writing therapy prescriptions and developing individualized treatment plans. Chapters are written by teams of musculoskeletal physicians, allied health professionals, and trainees to underscore the importance of collaboration in designing programs and improving outcomes. The book employs a literature- driven treatment approach to the common musculoskeletal problems that clinicians encounter on a daily basis. Each condition-specific chapter includes clinical background and presentation, physical examination, and diagnostics, followed by a comprehensive look at the rehabilitation program. Case examples with detailed therapy prescriptions reinforce key points. The book includes a bound-in DVD with downloadable patient handouts for most conditions. Therapeutic Programs for Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorders Features: n A concise but comprehensive approach to the conservative treatment of musculoskeletal disorders n A focus on developing individualized treatment plans incorporating physical Wyss Musculoskeletal modalities, manual therapy, and therapeutic exercise n A logical framework for writing effective therapy-based prescriptions for common limb and spine problems n Case examples with detailed therapy prescriptions n n A targeted review of the associated literature in each condition-specific chapter Patel Disorders n A DVD with illustrated handouts covering home modalities and therapeutic exercises for key problems that can be provided to patients n n The first reference bringing together physicians, allied health professionals, and JAMES F. WYSS AMRISH D.