Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioarchaeological Implications of Calcaneal Spurs in the Medieval Nubian Population of Kulubnarti

Bioarchaeological Implications of Calcaneal Spurs in the Medieval Nubian Population of Kulubnarti Lindsay Marker Department of Anthropology Primary Thesis Advisor Matthew Sponheimer, Department of Anthropology Defense Committee Members Douglas Bamforth, Department of Anthropology Patricia Sullivan, Department of English University of Colorado at Boulder April 2016 1 Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 4 Abstract …................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: Introduction …........................................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Anatomy …................................................................................................................ 11 2.1 Chapter Overview …................................................................................................. 11 2.2 Bone Composition …................................................................................................ 11 2.3 Plantar Foot Anatomy …........................................................................................... 12 2.4 Posterior Foot Anatomy …........................................................................................ 15 Chapter 3: Literature Review and Background of Calcaneal Enthesophytes ............................. 18 3.1 Chapter Overview …................................................................................................ -

9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease

Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease 121 9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease A. Stäbler CONTENTS Shoulder pain and chronic reduced function are fre- quently heard complaints in an orthopaedic outpa- 9.1 Defi nition of Impingement Syndrome 122 tient department. The symptoms are often related to 9.2 Stages of Impingement 123 the unique anatomic relationships present around the 9.3 Imaging of Impingement Syndrome: Uri Imaging Modalities 123 glenohumeral joint ( 1997). Impingement of the 9.3.1 Radiography 123 rotator cuff and adjacent bursa between the humeral 9.3.2 Ultrasound 126 head and the coracoacromial arch are among the most 9.3.3 Arthrography 126 common causes of shoulder pain. Neer noted that 9.3.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging 127 elevation of the arm, particularly in internal rotation, 9.3.4.1 Sequences 127 9.3.4.2 Gadolinium 128 causes the critical area of the cuff to pass under the 9.3.4.3 MR Arthrography 128 coracoacromial arch. In cadaver dissections he found 9.4 Imaging Findings in Impingement Syndrome alterations attributable to mechanical impingement and Rotator Cuff Tears 130 including a ridge of proliferative spurs and excres- 9.4.1 Bursal Effusion 130 cences on the undersurface of the anterior margin 9.4.2 Imaging Following Impingement Test Injection 131 Neer Neer 9.4.3 Tendinosis 131 of the acromion ( 1972). Thus it was who 9.4.4 Partial Thickness Tears 133 introduced the concept of an impingement syndrome 9.4.5 Full-Thickness Tears 134 continuum ranging from chronic bursitis and partial 9.4.5.1 Subacromial Distance 136 tears to complete tears of the supraspinatus tendon, 9.4.5.2 Peribursal Fat Plane 137 which may extend to involve other parts of the cuff 9.4.5.3 Intramuscular Cysts 137 Neer Matsen 9.4.6 Massive Tears 137 ( 1972; 1990). -

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint in the human body, but this same characteristic also makes it the least stable joint.1-3 The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that are important in supporting the glenohumeral joint, essential in almost every type of shoulder movement.4 These muscles maintain dynamic joint stability which not only avoids mechanical obstruction but also increases the functional range of motion at the joint.1,2 However, dysfunction of these stabilizers often leads to a complex pattern of degeneration, rotator cuff tear arthropathy that often involves subacromial impingement.2,22 Rotator cuff tear arthropathy is strikingly prevalent and is the most common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction.3,4 It appears to be age-dependent, affecting 9.7% of patients aged 20 years and younger and increasing to 62% of patients of 80 years and older ( P < .001); odds ratio, 15; 95% CI, 9.6-24; P < .001.4 Etiology for rotator cuff pathology varies but rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy are most common in athletes and the elderly.12 It can be the result of a traumatic event or activity-based deterioration such as from excessive use of arms overhead, but some argue that deterioration of these stabilizers is part of the natural aging process given the trend of increased deterioration even in individuals who do not regularly perform overhead activities.2,4 The factors affecting the rotator cuff and subsequent treatment are wide-ranging. The major objectives of this exposition are to describe rotator cuff anatomy, biomechanics, and subacromial impingement; expound upon diagnosis and assessment; and discuss surgical and conservative interventions. -

IGHS Poster 01: History of the Australian Hand Surgery Society

IGHS Poster 01: History of the Australian Hand Surgery Society Category: Other Keyword: Other Not a clinical study ♦ Michael Tonkin, MD ♦ Richard Honner, MD Hypothesis: The Australian Hand Club was established in 1972, following discussion between members of the New South Wales Hand Surgery Association and the plastic surgeons of Melbourne under the direction of Sir Benjamin Rank, who became the first President. The other elected Office Bearers were: President Elect - Alan McJannet Secretary - Frank Harvey Treasurer - Richard Honner Committee Members - Peter Millroy, Don Robinson, Bernard O’Brien In 1990 the name was changed to the Australian Hand Surgery Society. This now has 159 active members, 18 overseas members, 28 honorary members and 9 provisional members. The current Board consists of: President - Randall Sach President Elect - David Stabler Ex-officio President - Stephen Coleman Secretary - Philip Griffin Treasurer - Douglass Wheen Executive Committee - Anthony Beard, David McCombe, Jeffrey Ecker An Annual Scientific Meeting with overseas Guest Professors is conducted each year, often associated with a separate two day program in hand surgery for Registrars on surgical training schemes in Australia and New Zealand. The AHSS also convenes hand surgery programmes for the Annual Scientific Meetings of the Australian Orthopaedic Association and the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Combined meetings with other hand surgery societies have been held, including with New Zealand, Singapore and most recently with the ASSH in Kauai, USA, March 2012. The AHSS became a member of the International Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand (IFSSH) in 1977 and was a founding member of the Asia-Pacific Federation of Societies for Surgery of the Hand (APFSSH) in 1997. -

Imaging Shoulder Impingement

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Imaging shoulder impingement. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0kg9j32r Journal Skeletal radiology, 22(8) ISSN 0364-2348 Authors Gold, RH Seeger, LL Yao, L Publication Date 1993-11-01 DOI 10.1007/bf00197135 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Skeletal Radiol (1993) 22:555-561 Skeletal Radiology Review Imaging shoulder impingement Richard H. Gold, M.D., Leannc L. Seeger, M.D., Lawrence Yao, M.D. Department of Radiological Sciences, UCLA School of Medicine, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1721, USA Abstract. Appropriate imaging and clinical examinations more components of the coracoacromial arch superiorly. may lead to early diagnosis and treatment of the shoulder The coracoacromial arch is composed of five basic struc- impingement syndrome, thus preventing progression to a tures: the distal clavicle, acromioclavicular joint, anteri- complete tear of the rotator cuff. In this article, we discuss or third of the acromion, coracoacromial ligament, and the anatomic and pathophysiologic bases of the syn- anterior third of the coracoid process (Fig. 1). Repetitive drome, and the rationale for certain imaging tests to eval- trauma leads to progressive edema and hemorrhage of uate it. Special radiographic projections to show the the rotator cuff and hypertrophy of the synovium and supraspinatus outlet and inferior surface of the anterior subsynovial fat of the subacromial bursa. In a vicious third of the acromion, combined with magnetic reso- cycle, the resultant loss of space predisposes the soft nance images, usually provide the most useful informa- tissues to further injury, with increased pain and disabili- tion regarding the causes of impingement. -

Imaging in Gout and Other Crystal-Related Arthropathies 625

ImaginginGoutand Other Crystal-Related Arthropathies a, b Patrick Omoumi, MD, MSc, PhD *, Pascal Zufferey, MD , c b Jacques Malghem, MD , Alexander So, FRCP, PhD KEYWORDS Gout Crystal arthropathy Calcification Imaging Radiography Ultrasound Dual-energy CT MRI KEY POINTS Crystal deposits in and around the joints are common and most often encountered as inci- dental imaging findings in asymptomatic patients. In the chronic setting, imaging features of crystal arthropathies are usually characteristic and allow the differentiation of the type of crystal arthropathy, whereas in the acute phase and in early stages, imaging signs are often nonspecific, and the final diagnosis still relies on the analysis of synovial fluid. Radiography remains the primary imaging tool in the workup of these conditions; ultra- sound has been playing an increasing role for superficially located crystal-induced ar- thropathies, and computerized tomography (CT) is a nice complement to radiography for deeper sites. When performed in the acute stage, MRI may show severe inflammatory changes that could be misleading; correlation to radiographs or CT should help to distinguish crystal arthropathies from infectious or tumoral conditions. Dual-energy CT is a promising tool for the characterization of crystal arthropathies, partic- ularly gout as it permits a quantitative assessment of deposits, and may help in the follow-up of patients. INTRODUCTION The deposition of microcrystals within and around the joint is a common phenomenon. Intra-articular microcrystals -

ESSR 2013 | 1 2 | ESSR 2013 Essrsport 2013 Injuries Musculoskeletal Radiology June 13–15, MARBELLA/SPAIN

Final Programme property of Marbella City Council ESSRSport 2013 Injuries MUSCULOSKELETAL RADIOLOGY JUNE 13–15, MARBELLA/SPAIN ESSRSport 2013 Injuries MUSCULOSKELETAL RADIOLOGY JUNE 13–15, MARBELLA/SPAIN Content 3 Welcome 4–5 ESSR Committee & Invited Speakers 6 General Information 11/13 Programme Overview ESSR 2013 | 1 2 | ESSR 2013 ESSRSport 2013 Injuries MUSCULOSKELETAL RADIOLOGY JUNE 13–15, MARBELLA/SPAIN from the ESSR 2013 Congress President ME Welcome LCO On behalf of the ESSR it is a pleasure to invite you to participate in the 20th Annual Scientific Meeting WE of the European Skeletal Society to be held in Marbella, Spain, on June 13–15, 2013, at the Palacio de Congresos located in the center of the city. The scientific programme will focus on “Sports Lesions”, with a refresher course lasting two days dedicated to actualised topics. The programme will include focus sessions and hot topics, as well as different sessions of the subcommittees of the society. There will be a special session on Interventional Strategies in Sports Injuries. The popular “hands on” ultrasound workshops in MSK ultrasound will be held on Thursday 13, 2013, during the afternoon, with the topic of Sports Lesions. Basic and advanced levels will be offered. A state-of-the-art technical exhibition will display the most advanced technical developments in the area of musculoskeletal pathology. The main lobby will be available for workstations for the EPOS as well as technical exhibits. Marbella is located in the south of Spain, full of life and with plenty of cultural and tourist interest, with architectural treasures of the traditional and popular Andalusian culture. -

Open Fracture As a Rare Complication of Olecranon Enthesophyte in a Patient with Gout Rafid Kakel, MD, and Joseph Tumilty, MD

A Case Report & Literature Review Open Fracture as a Rare Complication of Olecranon Enthesophyte in a Patient With Gout Rafid Kakel, MD, and Joseph Tumilty, MD has been reported in the English literature. The patient Abstract provided written informed consent for print and elec- Enthesophytes are analogous to osteophytes of osteo- tronic publication of this case report. arthritis. Enthesopathy is the pathologic change of the enthesis, the insertion site of tendons, ligaments, and CASE REPORT joint capsules on the bone. In gout, the crystals of mono- A 50-year-old man with chronic gout being treated with sodium urate monohydrate may provoke an inflamma- tory reaction that eventually may lead to ossification at allopurinol (and indomethacin on an as-needed basis) those sites (enthesophytes). Here we report the case of presented to the emergency department. He reported a man with chronic gout who sustained an open fracture of an olecranon enthesophyte when he fell on his left elbow. To our knowledge, no other case of open fracture of an enthesophyte has been reported in the English literature. nthesophytes are analogous to osteophytes of osteoarthritis. Enthesopathy is the pathologic change of the enthesis, the insertion site of ten- dons, ligaments, and joint capsules on the bone. EEnthesopathy occurs in a wide range of conditions, notably spondyloarthritides, crystal-induced diseases, and repeated minor trauma to the tendinous attach- ments to bones. Enthesopathy can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. In gout, crystals of monosodium urate are found in and around the joints—the cartilage, epiphyses, synovial membrane, tendons, ligaments, and enthesis. Figure 1. Small wound at patient’s left elbow. -

Clinical and Imaging Assessment of Peripheral Enthesitis in Ankylosing Spondylitis

Special RepoRt Clinical and imaging assessment of peripheral enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis Enthesitis, defined as inflammation of the origin and insertion of ligaments, tendons, aponeuroses, annulus fibrosis and joint capsules, is a hallmark of ankylosing spondylitis. The concept of entheseal organ prone to pathological changes in ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthritis is well recognized. The relevant role of peripheral enthesitis is supported by the evidence that this feature, on clinical examination, has been included in the classification criteria of Amor (heel pain or other well-defined enthesopathic pain), European Spondiloarthropathy Study Group and Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society for axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Nevertheless, the assessment of enthesitis has been improved by imaging techniques to carefully detect morphological abnormalities and to monitor disease activity. 1 Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis n clinical assessment n enthesitis n MrI Antonio Spadaro* , n spondyloarthritis n ultrasound Fabio Massimo Perrotta1, In primary ankylosing spondylitis (AS) the fre- has proven to be a highly sensitive and nonin- Alessia Carboni1 quency of peripheral enthesitis has been found vasive tool to assess the presence of enthesitis, & Antongiulio Scarno1 to be between 25 and 58% [1], however, the real characterized by hypoechogenicity with loss 1Dipartimento di Medicina Interna e prevalence of this feature depends on the type of tendon fibrillar pattern, tendon thickening, Specialità -

Relationships Between Ultrasound Enthesitis, Disease Activity and Axial Radiographic Structural Changes in Patients with Early S

Spondyloarthritis RMD Open: first published as 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000482 on 7 September 2017. Downloaded from ORIGINAL articLE Relationships between ultrasound enthesitis, disease activity and axial radiographic structural changes in patients with early spondyloarthritis: data from DESIR cohort Adeline Ruyssen-Witrand,1,2,3 Bénédicte Jamard,1 Alain Cantagrel,1,3,4 Delphine Nigon,1 Damien Loeuille,5 Yannick Degboe,4 Arnaud Constantin1,3,4 To cite: Ruyssen-Witrand A, ABSTRACT Jamard B, Cantagrel A, Background To search for association between Key messages et al. Relationships between ultrasound (US) enthesis abnormalities and disease activity, ultrasound enthesitis, disease spine and sacro-iliac joints (SIJ) MRI inflammatory lesions What is already known about this subject? activity and axial radiographic and spine structural changes in a cohort of patients ► The association between disease activity and structural changes in patients suspected for axial spondyloarthritis (SpA). enthesis ultrasound findings is not clear in the with early spondyloarthritis: data literature. from DESIR cohort. RMD Open Methods Patients: Of 708 patients included in the 2017;3:e000482. doi:10.1136/ DESIR(Devenir des Spondyloarthrites Indifférenciées What does this study add? Récentes) cohort, 402 had an US enthesis assessment rmdopen-2017-000482 ► Ultrasound peripheral enthesitis was not associated and were selected for this study. Imaging: Achilles, lateral with clinical disease activity in patients with early epicondyles, superior patellar ligament, inferior patellar ► Prepublication history and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA). ligament entheses were systematically US scanned additional material is available. ► Ultrasound peripheral enthesitis was not associated To view, please visit the journal and abnormalities were summed in US structural and with sacroiliitis nor with MRI spine inflammatory online (http:// dx. -

A Narrative Review of the Classification and Use Of

diagnostics Review A Narrative Review of the Classification and Use of Diagnostic Ultrasound for Conditions of the Achilles Tendon Sheryl Mascarenhas Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 543 Taylor Ave, Columbus, OH 43203, USA; [email protected] Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 4 November 2020; Published: 13 November 2020 Abstract: Enthesitis is a cardinal feature of spondyloarthropathies. The Achilles insertion on the calcaneus is a commonly evaluated enthesis located at the hindfoot, generally resulting in hindfoot pain and possible tendon enlargement. For decades, diagnosis of enthesitis was based upon patient history of hindfoot or posterior ankle pain and clinical examination revealing tenderness and/or enlargement at the site of the tendon insertion. However, not all hindfoot or posterior ankle symptoms are related to enthesitis. Advanced imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound (US), has allowed for more precise evaluation of hindfoot and posterior ankle conditions. Use of US in diagnosis has helped confirm some of these cases but also identified other conditions that may have otherwise been misclassified without use of advanced imaging diagnostics. Conditions that may result in hindfoot and posterior ankle symptoms related to the Achilles tendon include enthesitis (which can include retrocalcaneal bursitis and insertional tendonopathy), midportion tendonopathy, paratenonopathy, superficial calcaneal bursitis, calcaneal ossification (Haglund deformity), and calcific tendonopathy. With regard to classification of these conditions, much of the existing literature uses confusing nomenclature to describe conditions in this region of the body. Some terminology may imply inflammation when in fact there may be none. A more uniform approach to classifying these conditions based off anatomic location, symptoms, clinical findings, and histopathology is needed. -

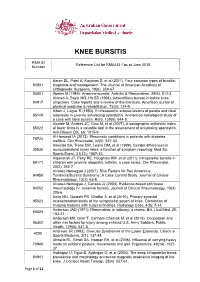

Reference List for RMA431-1As at June 2018 Number

KNEE BURSITIS RMA ID Reference List for RMA431-1as at June 2018 Number Aaron DL, Patel A, Kayiaros S, et al (2011). Four common types of bursitis: 84931 diagnosis and management. The Journal of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 19(6): 359-67. 85001 Abeles M (1986). Anserine bursitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 29(6): 812-3. Ahmed A, Bayol MG, Ha SB (1994). Adventitious bursae in below knee 84917 amputees. Case reports and a review of the literature. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 73(2): 124-9. Albert J, Lagier R (1983). Enthesopathic erosive lesions of patella and tibial 85148 tuberosity in juvenile ankylosing spondylitis. Anatomico-radiological study of a case with tibial bursitis. Rofo, 139(5): 544-8. Alcalde M, Acebes JC, Cruz M, et al (2007). A sonographic enthesitic index 85022 of lower limbs is a valuable tool in the assessment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis, 66: 1015-9. Al-Homood IA (2013). Rheumatic conditions in patients with diabetes 78722 mellitus. Clin Rheumatol, 32(5): 527-33. Almeida SA, Trone DW, Leone DM, et al (1999). Gender differences in 39530 musculoskeletal injury rates: a function of symptom reporting. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31(12): 1807-12. Alqanatish JT, Petty RE, Houghton KM, et al (2011). Infrapatellar bursitis in 85171 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case series. Clin Rheumatol, 30(2): 263-7. Alvarez-Nemegyei J (2007). Risk Factors for Pes Anserinus 84950 Tendinitis/Bursitis Syndrome: A Case Control Study. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 13(2): 63-5. Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Canoso JJ (2004). Evidence-based soft tissue 84552 rheumatology IV: anserine bursitis.