The Bazigar (Goaar) People and Their Performing Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATION, NATIONALISM and the PARTITION of INDIA: PARTITION the NATION, and NATIONALISM , De Manzoor Ehtesham

NATION, NATIONALISM AND THE PARTITION OF INDIA: TWO MOMENTS FROM HINDI FICTION* Bodh Prakash Ambedkar University, Delhi Abstract This paper traces the trajectory of Muslims in India over roughly four decades after Independ- ence through a study of two Hindi novels, Rahi Masoom Reza’s Adha Gaon and Manzoor Ehtesham’s Sookha Bargad. It explores the centrality of Partition to issues of Muslim identity, their commitment to the Indian nation, and how a resurgent Hindu communal discourse particularly from the 1980s onwards “otherizes” a community that not only rejected the idea of Pakistan as the homeland for Muslims, but was also critical to the construction of a secular Indian nation. Keywords: Manzoor Ehtesham, Partition in Hindi literature, Rahi Masoom. Resumen Este artículo estudia la presencia del Islam en India en las cuatro décadas siguientes a la Independencia, según dos novelas en hindi, Adha Gaon, de Rahi Masoom Reza y Sookha Bargad, de Manzoor Ehtesham. En ambas la Partición es el eje central de la identidad mu- sulmana, que en todo caso mantiene su fidelidad a la nación india. Sin embargo, el discurso del fundamentalismo hindú desde la década de 1980 ha ido alienando a esta comunidad, 77 que no solo rechazó la idea de Paquistán como patria de los musulmanes, sino que fue fundamental para mantener la neutralidad religiosa del estado en India. Palabras clave: Manzoor Ehtesham, Partición en literatura hindi, Rahi Masoom. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25145/j.recaesin.2018.76.06 Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, 76; April 2018, pp. 77-89; ISSN: e-2530-8335 REVISTA CANARIA 77-89 DE ESTUDIOS PP. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

08 July 2021, Is Enclosed at Annex A

Page 1 of3 MOST IMMEDIATE/BY FAX F.2 (E)/2020-NDMA (MW/ Press Release) Government of Pakistan Prime Minister's Office National Disaster Management Authority ISLAMABAD NDMA Dated: 08 July, 2021 Subject: Rain-wind / Thundershower predicted in upper & central parts from weekend (Monsoon likely to remain in active phase during 10-14 July 2021 concerned Fresh PMD Press Release dated 08 July 2021, is enclosed at Annex A. All measures to avoid any loss of life or are requested to ensure following precautionary property: FWO and a. Respective PDMAs to coordinate with concerned departments (NHA, obstruction. C&W) for restoration of roads in case of any blockage/ . Tourists/Visitors in the area be apprised about weather forecast C. Availability of staff of emergency services be ensured. Coordinate with relevant district and municipal administration to ensure d. mitigation measures for urban flooding and to secure or remove billboards/ hoardings in light of thunderstorm/ high winds the threat. e. Residents of landslide prone areas be apprised about In case of any eventuality, twice daily updates should be shared with NDMA. f. 2 Forwarded for information / necessary action, please. Lieutenant Colonel For Chainman NDMA (Muhammad Ala Ud Din) Tel: 051-9087874 Fax: 051 9205086 To Director General, PDMA Punjab Lahore Director General, PDMA Balochistan, Quetta Director General, PDMA Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Peshawar Director General, SDMA Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad Director General, GBDMA Gilgit Baltistan, Gilgit General Manager, National Highways Authority -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

Politics of Nawwab Gurmani

Politics of Accession in the Undivided India: A Case Study of Nawwab Mushtaq Gurmani’s Role in the Accession of the Bahawalpur State to Pakistan Pir Bukhsh Soomro ∗ Before analyzing the role of Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani in the affairs of Bahawalpur, it will be appropriate to briefly outline the origins of the state, one of the oldest in the region. After the death of Al-Mustansar Bi’llah, the caliph of Egypt, his descendants for four generations from Sultan Yasin to Shah Muzammil remained in Egypt. But Shah Muzammil’s son Sultan Ahmad II left the country between l366-70 in the reign of Abu al- Fath Mumtadid Bi’llah Abu Bakr, the sixth ‘Abbasid caliph of Egypt, 1 and came to Sind. 2 He was succeeded by his son, Abu Nasir, followed by Abu Qahir 3 and Amir Muhammad Channi. Channi was a very competent person. When Prince Murad Bakhsh, son of the Mughal emperor Akbar, came to Multan, 4 he appreciated his services, and awarded him the mansab of “Panj Hazari”5 and bestowed on him a large jagir . Channi was survived by his two sons, Muhammad Mahdi and Da’ud Khan. Mahdi died ∗ Lecturer in History, Government Post-Graduate College for Boys, Dera Ghazi Khan. 1 Punjab States Gazetteers , Vol. XXXVI, A. Bahawalpur State 1904 (Lahore: Civil Military Gazette, 1908), p.48. 2 Ibid . 3 Ibid . 4 Ibid ., p.49. 5 Ibid . 102 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XXV/2 (2004) after a short reign, and confusion and conflict followed. The two claimants to the jagir were Kalhora, son of Muhammad Mahdi Khan and Amir Da’ud Khan I. -

Internal Classification of Scheduled Castes: the Punjab Story

COMMENTARY “in direct recruitments only and not in Internal Classification of promotion cases”.2 Learning from the Punjab experience, the state government Scheduled Castes: of Haryana too decided in 1994 to divide its scheduled caste population in two blocks, The Punjab Story A and B, limiting 50 per cent of all the seats for the chamars (block B) and offer- ing 50 per cent of the seats to non-chamars Surinder S Jodhka, Avinash Kumar (block A) on preferential basis. This arrangement worked well until Much before the question of n the recommendations of the 2005 when the Punjab and Haryana High quotas within quotas in jobs Ramachandra Rao Commission, Court directed the two state governments reserved for the scheduled castes Othe government of Andhra about the “illegality” of the provision in Pradesh decided in June 1997 to classify response to a writ petition by Gaje Singh, acquired prominence in Andhra its scheduled caste (SC) population into A, a chamar from the region. The petitioner Pradesh, Punjab had introduced a B, C and D categories and fixed a specific cited the Supreme Court judgments twofold classification of its SC quota of seats against each of the caste against the sub-classification of scheduled population. When the Andhra categories roughly matching the propor- castes in the case of Andhra Pradesh. tion of their numbers in the total popula- Though, the Punjab state government case went to court, Punjab had to tion. This was done in response to the pow- quickly worked a way out of it and turned rework its policy. -

Barinder Kaur

Barinder Kaur (Dr.) 11,Sangam Vihar, P.O.Chogitty Principal Jalandhar-144009(Pb.) Mata Sundri University Girls College Phone:-0181-2412033(R) Mansa,Punjab,INDIA Email:[email protected] Mob.92562-15590, 98885-11223 Summary Approved Principal by Punjab University Chandigarh, Punjabi University Patiala, Approved Lecturer by Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar & D.PI.(C) Chandigarh. Ph.D. (Research work Published), M.Phil. (First class first with distinction), M.A (First division). Presented Punjabi news at DoorDarshan Kendra, jalandhar for more then two decades.Anchor for Khas Khabar Ik Nazar & RUBRU etc. Founder Editor in Chief of College Magazine ‘Aadjugaad’ (Trai shatabadi G.G.S Khalsa college, Amritsar), Started Publication in 2001-2002. Started another Publication of college magazine Pritam Prerna of G.G.S College for Women, Kamalpur in 2008(3 Issues). Secured ‘B’ Grade in Hockey Adjudged by Sports Department, Chandigarh. Executive Member of Sports Sub-committee of S.G.P.C Amritsar from 2002- 2006. Recipient of Best Citizen of India Award -2004 by International Publishing House, New Dehli. Received Rural Olympic Heritage Award-2010 at 75th Qila Raipur Sports festival known as Mini Olympics. Recipient of SMISS AWARD-2010 by shaheed Memorial sewa society(regd.)Ludhiana. Recipient of ‘Best Principal’s Awardi-2011’ by International Institute of Management & Education, New Dehli. Executive Member, Punjab University Chandigarh Sports Committee 2010- 2011 & GNDU, Amritsar 2012-14. Manager of Punjab University Chandigarh Net Ball Women’s team & won Inter University Championship in 2010-2011. Member of Program Committee organized 28th ‘North-Zone Inter-University’ Youth Festival held at GNDU, Amritsar from 7th-11th Nov. -

United Punjab: Exploring Composite Culture in a New Zealand Punjabi Film Documentary

sites: new series · vol 16 no 2 · 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11157/sites-id445 – article – SANJHA PUNJAB – UNITED PUNJAB: EXPLORING COMPOSITE CULTURE IN A NEW ZEALAND PUNJABI FILM DOCUMENTARY Teena J. Brown Pulu,1 Asim Mukhtar2 & Harminder Singh3 ABSTRACT This paper examines the second author’s positionality as the researcher and sto- ryteller of a PhD documentary film that will be shot in New Zealand, Pakistan, and North India. Adapting insights from writings on Punjab’s composite culture, the film will begin by framing the Christchurch massacre at two mosques on 15 March 2019 as an emotional trigger for bridging Punjabi migrant communi- ties in South Auckland, prompting them to reimagine a pre-partition setting of ‘Sanjha Punjab’ (United Punjab). Asim Mukhtar’s identity as a Punjabi Muslim from Pakistan connects him to the Punjabi Sikhs of North India. We use Asim’s words, experiences, and diary to explore how his insider role as a member of these communities positions him as the subject of his research. His subjectivity and identity then become sense-making tools for validating Sanjha Punjab as an enduring storyboard of Punjabi social memory and history that can be recorded in this documentary film. Keywords: united Punjab; composite culture; migrants; Punjabis; Pakistani; Muslims; Sikhs; South Auckland. INTRODUCTION The concept ‘Sanjha Punjab – United Punjab’ cuts across time, international and religious boundaries. On March 15, 2019, this image of a united Punjab inspired Pakistani Muslim Punjabis and Indian Sikh Punjabis to cooperate in support of Pakistani families caught in the terrorist attacks at Al Noor Masjid and Linwood Majid in Christchurch. -

Akshay Kumar

Akshay Kumar Topic relevant selected content from the highest rated wiki entries, typeset, printed and shipped. Combine the advantages of up-to-date and in-depth knowledge with the convenience of printed books. A portion of the proceeds of each book will be donated to the Wikimedia Foundation to support their mis- sion: to empower and engage people around the world to collect and develop educational content under a free license or in the public domain, and to disseminate it effectively and globally. The content within this book was generated collaboratively by volunteers. Please be advised that nothing found here has necessarily been reviewed by people with the expertise required to provide you with complete, accu- rate or reliable information. Some information in this book maybe misleading or simply wrong. The publisher does not guarantee the validity of the information found here. If you need specific advice (for example, medi- cal, legal, financial, or risk management) please seek a professional who is licensed or knowledgeable in that area. Sources, licenses and contributors of the articles and images are listed in the section entitled “References”. Parts of the books may be licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. A copy of this license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License” All used third-party trademarks belong to their respective owners. Contents Articles Akshay Kumar 1 List of awards and nominations received by Akshay Kumar 8 Saugandh 13 Dancer (1991 film) 14 Mr Bond 15 Khiladi 16 Deedar (1992 film) 19 Ashaant 20 Dil Ki Baazi 21 Kayda Kanoon 22 Waqt Hamara Hai 23 Sainik 24 Elaan (1994 film) 25 Yeh Dillagi 26 Jai Kishen 29 Mohra 30 Main Khiladi Tu Anari 34 Ikke Pe Ikka 36 Amanaat 37 Suhaag (1994 film) 38 Nazar Ke Samne 40 Zakhmi Dil (1994 film) 41 Zaalim 42 Hum Hain Bemisaal 43 Paandav 44 Maidan-E-Jung 45 Sabse Bada Khiladi 46 Tu Chor Main Sipahi 48 Khiladiyon Ka Khiladi 49 Sapoot 51 Lahu Ke Do Rang (1997 film) 52 Insaaf (film) 53 Daava 55 Tarazu 57 Mr. -

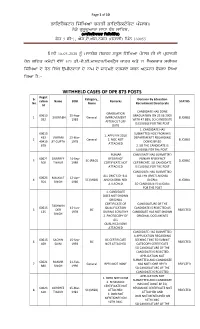

WITHHELD CASES of DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr

Page 1 of 10 fwierYktr is`iKAw BrqI fwierYktoryt pMjwb[ nyVy gurUduAwrw swcw DMn swihb, (mweIkrosw&t ibilifMg) Pyz 3 bI-1, AYs.ey.AYs.ngr (mohwlI) ipMn 160055 imqI 16.03.2020 nUM mwnXog s`kqr skUl is`iKAw pMjwb jI dI pRDwngI hyT giTq kmytI v`loN 873 fI.pI.eI.mwstr/imstRYs kwfr Aqy 74 lYkcrwr srIrk is`iKAw dy hyT ilKy aumIdvwrW dy nwm dy swhmxy drswey kQn Anuswr PYslw ilAw igAw hY:- WITHHELD CASES OF DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr. Category_ Decision By Education ration Name DOB Remarks STATUS No. Name Recruitment Directorate Id CANDIDATE HAS DONE GRADUATION 60610 25-Aug- GRADUATION ON 25.06.2005 1 SAURABH General IMPROVEMENT ELIGIBLE 352 1983 WITH 47.88%, SO CANDIDATE AFTER CUT OFF IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST DATE 1. CANDIDATE HAS 60613 SUBMITTED NOC FROM HIS 1. APPLY IN 2016 433 VIKRAM 23-Mar- DEPARTMENTT REGARDING 2 General 2. NOC NOT ELIGIBLE 40410 JIT GUPTA 1978 DOING BP.ED ATTACHED 679 2. SO THE CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST. PUNJAB CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED 60621 GURPREE 14-Sep- RESIDENCE PUNJAB RESIDENCE 3 SC (R&O) ELIGIBLE 500 T KAUR 1989 CERTIFICATE NOT CERTIFICATE SO CANDIDATE ATTACHED IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED ALL DMC'S OF B.A. ALL THE DMC'S AND BA 60625 MALKEET 12-Apr- 4 SC (M&B) AND DEGREE NOT DEGREE ELIGIBLE 504 SINGH 1986 ATTACHED SO CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST 1. CANDIDATE DOES NOT SHOWN ORIGINAL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDATURE OF THE TASHWIN 60615 15-Jun- QUALIFICATION CANDIDATE IS REJECTED AS 5 DER BC REJECTED 125 1978 DURING SCRUTINY CANDIDATE HAS NOT SHOWN SINGH 2. -

Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Locus Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes Susceptibility in Sikhs of Punjabi Origin from India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Harvard University - DASH Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Locus Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes Susceptibility in Sikhs of Punjabi Origin From India The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Saxena, R., D. Saleheen, L. F. Been, M. L. Garavito, T. Braun, A. Bjonnes, R. Young, et al. 2013. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Locus Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes Susceptibility in Sikhs of Punjabi Origin From India.” Diabetes 62 (5): 1746-1755. doi:10.2337/db12-1077. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db12-1077. Published Version doi:10.2337/db12-1077 Accessed February 16, 2015 1:14:24 PM EST Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12407045 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms- of-use#LAA (Article begins on next page) ORIGINAL ARTICLE Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Locus Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes Susceptibility in Sikhs of Punjabi Origin From India Richa Saxena,1 Danish Saleheen,2,3,4 Latonya F. Been,5 Martha L. Garavito,5 Timothy Braun,5 Andrew Bjonnes,1 Robin Young,3 Weang Kee Ho,3 Asif Rasheed,2 Philippe Frossard,2 Xueling Sim,6,7 Neelam Hassanali,8 Venkatesan Radha,9 Manickam Chidambaram,9 Samuel Liju,9 Simon D. -

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report Submitted to Mr. Rahul Gandhi General Secretary All India Congress Committee New Delhi BY Dr. Chandrashekar Naik Dr.D Paramesha Naik B.E,M.Tech,M.B.A,M.Phil Ph.D M.Sc, M.Phil, Ph.D, FISEC Congress & Banjara – Activist Congress & Banjara – Activist Mobile: +91-9379945100 Mobile: +91-9844250997 [email protected] [email protected] 2012 About Banjaras The Banjaras are the largest and historic formed group in India and also known as Lambadi or Lambani. The Banjara people are a people who speak lambadi or Lambani. All gypsy languages are linked linguistically, stemming from ancient Sanskrit and belonging to the North Indo-Aryan language family. Lambadi is the heart language of the Banjara, but it has no written script. The Banjara speak a second language of the state they live in and adopt that script. They are listed under 53 different names. Historically, these are the root Gypsies of earth. During the British colonial rule, these gypsy nomads of India were given the name Banjara, but they call themselves Ghor. The Banjaras are a colourful, versatile and one of the largest people groups of India, inhabiting most of the districts in India. The Banjara are a sturdy, ambitious people and have a light complexion. The Banjara were historically nomadic, keeping cattle, trading salt and transporting goods. Most of these people now have settled down to farming and various types of wage labour. Their habits of living in isolated groups away from other, which was a characteristic of their nomadic days, still persist.